In mid-April 1905, our party—consisting of Philip B. Stewart, of Colorado Springs, and Dr. Alexander Lambert, of New York, in addition to myself—left Newcastle, Colorado, for a bear hunt. As guides and hunters, we had John Goff and Jake Borah, whom there are no better men at their work of hunting bear in the mountains with hounds. Each brought his own dogs; all told, there were 26 hounds and four half-blood terriers to help worry the bear when at bay. We traveled in comfort, with a big pack train, spare horses for each of us, and a cook, packers, and horse wranglers. I carried one of the new model Springfield military rifles, a .30-40, with a soft-nosed bullet—a very accurate, hard-hitting gun.

The country was very steep and rugged; the mountainsides were greasy and slippery from the melting snow while the snow bucking through the deep drifts on their tops and on the north sides was exhausting. Only sure-footed animals could avoid serious tumbles, and only animals of great endurance could have lasted through the work. Both Johnny Goff and his partner, Brick Wells, who often accompanied us on the hunts, were frequently mounted on animals of uncertain temper, with a tendency to buck on insufficient provocation; but they rode them with entire indifference up and down any incline.

This Colorado trip was the first in which I hunted bears with hounds. If we had run across a grizzly there would doubtless have been a chance to show some prowess, at least in the way of hard riding. But the black and brown bears cannot, save under exceptional circumstances, escape from such a pack as we had with us; and the real merit of the chase was confined to the hounds and to Jake and Johnny for their skill in handling them.

The first day after reaching camp, we rode for eleven hours over difficult country, but without getting above the snowline. Finally, the dogs got on the fresh trail of a bobcat and away they went. A bobcat will often give a good run, much better, on the average, than a cougar, and this one puzzled the dogs not a little at first. It scrambled out of one deep valley, crossing and recrossing the rock ledges where its scent was hard to follow; then plunged into another valley. Meanwhile, we had ridden up on the high mountain spur between the two valleys, and after scrambling and galloping to and fro, as the cry veered from point to point, when the dogs changed directions, we saw them cross into the second valley. Here again they took a good deal of time to puzzle out the trail and became somewhat scattered.

We had dismounted and were standing by the hones’ heads, listening to the baying and trying to decide which way we should go, when Stewart suddenly pointed us out a bear. It was on the other side of the valley from us, and perhaps half a mile away, galloping downhill, with two of the hounds after it, and in the sunlight its fur looked glossy black. In a minute or two it passed out of sight in the thick-growing timber at the bottom of the valley; and as we afterward found, the two hounds, getting momentarily thrown out, and hearing the others still baying on the cat trail, joined the tatter. Jake started off to go around the head of the valley, while the rest of us plunged down into it. We found from the track that the bear had gone up the valley, and Jake found where he had come out on the high divide, and then turned and retraced his steps. But the hounds were evidently all after the cat.

There was nothing for us to do but follow them. Sometimes riding, sometimes leading the horses, we went up the steep hillside and, as soon as we reached the crest, heard the hounds barking treed. The dogs Shorty and Skip, who always trotted after the horses while the hounds were in full cry on a trail, recognized the change of note immediately, and tore off in the direction of the bay, while we followed as best we could, hoping to get there in time for Stewart and Lambert to take photographs of the lynx in a tree. But we were too late. Both Shorty and Skip could climb trees, and although Skip was too light to tackle a bobcat by himself, Shorty, a heavy, formidable dog, of unflinching courage and great physical strength, was altogether too much for any bobcat.

When we reached the place we found the bobcat in the top of a pinyon, and Shorty steadily working his way up through the branches and very near the quarry. Evidently the bobcat felt that the situation needed the taking of desperate chances, and, just before Shorty reached it out, it jumped, Shorty yelling with excitement as he plunged down through the branches after it. But the cat did not jump far enough. One of the hounds seized it by the hind leg and in another second everything was over.

Shorty was always the first of the pack to attack dangerous game, and in attacking bear or cougar, even, Badge was much less reckless and warier. In consequence, Shorty was seamed over with scars, most of them from bobcats, but one or two from cougars. He could speedily kill a bobcat single-handedly, for these small lynxes are not really formidable fighters, although they will lacerate a dog quite severely. Shorty found a badger a much more difficult antagonist than a bobcat. A bobcat in a hole makes a hard fight, however. On this hunt, we once got a bobcat under a big rock, and Jake’s Rowdy in trying to reach it got so badly mauled that he had to join the invalid class for several days.

The bobcat we killed this first day was a male, weighing 25 pounds. It was too late to try after the bear, especially as we had only ten or a dozen dogs out, while the bear’s tracks showed it to be a big one; and we rode back to camp.

The next morning we rode off early, taking with us all 25 hounds and the four terriers. We wished first to find whether the bear had gone out of the country in which we had seen him, and so rode up a valley and then scrambled laboriously up the mountainside to the top of the snow-covered divide. Here the snow was three feet deep in places, and the horses plunged and floundered as we worked our way in single file through the drifts. But it had frozen hard the previous night, so that a bear could walk on the crust and leave very little sign. In consequence, we came near passing over the place where the animal we were after had actually crossed out of the canyon-like ravine in which we had seen him and gone over the divide into another set of valleys.

The trail was so faint that it puzzled us, as we could not be certain how fresh it was, and until this point could be cleared up we tried to keep the hounds from following it. Old Jim, however, slipped off to one side and speedily satisfied himself that the trail was fresh. Along it he went, giving tongue, and the other dogs were maddened by the sound, while Jim, under such circumstances, paid no heed whatever to any effort to make him come back. Accordingly, the other hounds were slipped after him, and down they ran into the valley, while we slid, floundered, and scrambled along the ridge crest parallel to them, until a couple of miles farther on we worked our way down to some great slopes covered with dwarf scrub oak.

At the edge of these slopes, where they fell off in abrupt descent to the stream at the bottom of the valley, we halted. Opposite us was a high and very rugged mountainside covered with a growth of pinyon—never a close-growing tree—its precipitous flanks broken by ledges and scored by gullies and ravines. It was hard to follow the scent across such a mountainside, and the dogs speedily became much scattered. We could hear them plainly, and now and then could see them, looking like ants as they ran up and downhill and along the ledges. Finally, we heard some of them barking bayed. The volume of sound increased steadily as the straggling dogs joined those which had first reached the hunted animal.

At about this time, to our astonishment, Badge, usually a staunch fighter, rejoined us, followed by one or two other hounds who seemed to have had enough of the matter. Immediately afterward, we saw the bear, halfway up the opposite mountainside. The hounds were all around him and occasionally bit at his hindquarters, but he had evidently no intention of climbing a tree. When we first saw him he was sitting upon a point of rock surrounded by the pack, his black fur showing to fine advantage. Then he moved off, threatening the dogs, and making what in Mississippi is called a walking bay. He was a sullen, powerful beast, and his leisurely gait showed how little he feared the pack and how confident he was in his own burly strength.

By this time, the dogs had been after him for a couple of hours, and, as there was no water on the mountainside, we feared they might be getting exhausted, and rode toward them as rapidly as we could. It was a hard climb up to where they were, and we had to lead the horses.

Just as we came in sight of him, across a deep gully, which ran down the sheer mountainside, he broke bay and started off, threatening the foremost of the pack as they dared to approach him. They were all around him, and for a minute I could not fire; then as he passed under a pinyon I got a clear view of his great round stem and pulled the trigger. The bullet broke both his hips, and he rolled downhill, the hounds yelling with excitement as they closed in on him. He could still play havoc with the pack, and there was need to kill him at once. I leaped and slid down my side of the gully as he rolled down his; at the bottom he stopped and raised himself on his forequarters, and with another bullet I broke his back between the shoulders.

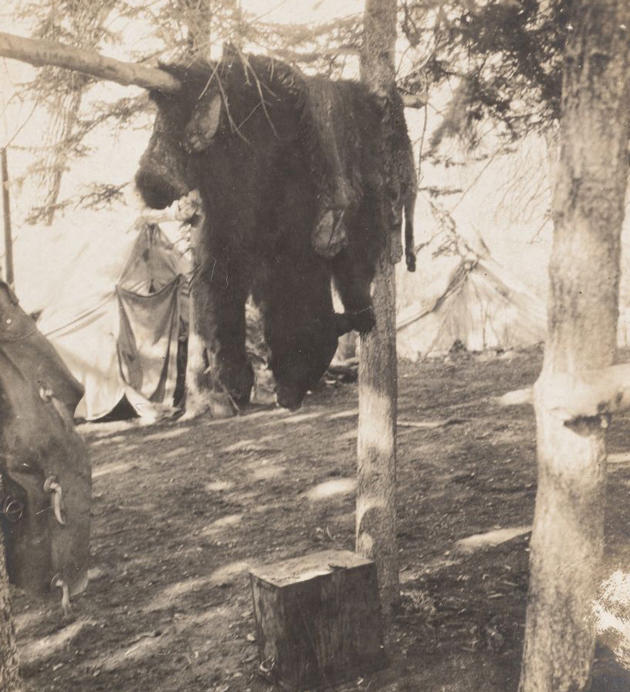

Immediately, all the dogs began to worry the carcass while their savage baying echoed so loudly in the narrow, steep gully that we could with difficulty hear one another speak. It was a wild scene to look upon, as we scrambled down to where the dead bear lay on his back between the rocks. He did not die wholly unavenged, for he had killed one of the terriers and six other dogs were more or less injured. The chase of the bear is grim work for the pack. Jim, usually a very wary fighter, had a couple of deep holes in his thigh, but the most mishandled of the wounded dogs was Shorty. With his usual dauntless courage, he had gone straight at the bear’s head. Being such a heavy, powerful animal, I think if he had been backed up he could have held the bear’s head down and prevented the beast from doing much injury. As it was, the bear bit through the side of Shorty’s head and bit him in the shoulder, and again in the hip, inflicting very bad wounds. Once the fight was over Shorty, lay down on the hillside, unable to move. When we started home we put him beside a little brook and left a piece of bear meat by him, as it was obvious we could not get him to camp that day.

The next day one of the boys went back with a packhorse to take Shorty in but halfway out met him struggling toward camp and returned. Late in the afternoon Shorty turned up while we were at dinner and staggered toward us, wagging his tail with enthusiastic delight at seeing his friends. We fed him until he could not hold another mouthful; then he curled up in a dry corner of the cook tent and slept for 48 hours, and two or three days afterward was able once more to go hunting.

Shorty

The bear was a big male, weighing 330 pounds. On examination at close quarters, his fur, which was in fine condition, was not as black as it had seemed when seen afar off, the roots of the hairs being brown. There was nothing whatsoever in his stomach. Evidently, he had not yet begun to eat and had been but a short while out of his hole. Bear feed very little when they first come out of their dens, sometimes beginning on grass, sometimes on buds. Occasionally, they will feed at carcasses and try to kill animals within a week or two after they have left winter quarters, but this is rare, and as a usual thing for the first few weeks after they have come out, they feed much as a deer would. Although not hog fat, as would probably have been the case in the fall, this bear was in good condition. In the fall, however, he would doubtless have weighed more than 400 pounds. +++

Be sure to sign up for our daily newsletter to get the latest from Sporting Classics straight to your inbox.

Photos via Harvard University Library. Text made available by the Internet Archive. Excerpted from Outdoor Pastimes of an American Hunter, Scribner’s Sons 1905.