Other hats await, too. Hats I will someday own. I don’t read the girly magazines any longer, but I’m still dog-earing and sweating up the catalogs.

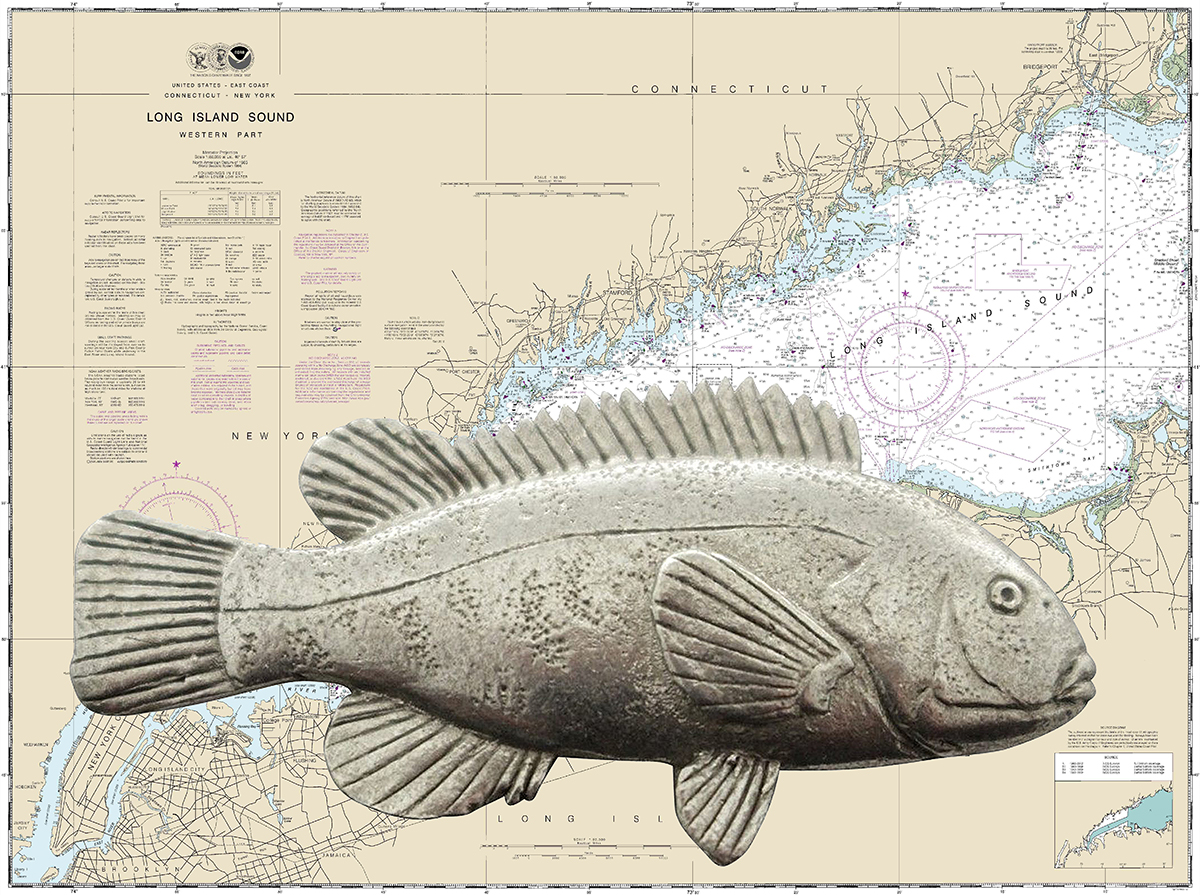

The boys blew ashore just a little after four. They had started out in the wee hours aboard the Marsh Hen, a 25-footer bound for the Gulf Stream, but they ran slap into a 20-knot northeaster just offshore. Second choice was the wreck of the Betsy Ross where they anchored and pitched and rolled and caught a bucket of Black Sea bass. But the wind got them there, too, and before long, they were struggling up my dock on the Cooper River.

They were a sorry and bedraggled lot coming up the wharf. Beek, wobbly and owlish in his salt-crusted glasses; Howie, chewing a cigar like something your cat leaves in the dark corner of your closet; J.D., reeling from sealers and his choice of refreshment; and finally, Ol’ Fred, struggling a cooler and wearing a four-day beard and a floppy white hat stained with diesel grease and fish blood. We congregate don my front porch, and the dark rum drinks went around and the sun began its long western slide and we ate fish and grits and fresh tomatoes and the clapper rails cackled when the tide changed directions at sundown.

They were a sorry and bedraggled lot coming up the wharf. Beek, wobbly and owlish in his salt-crusted glasses; Howie, chewing a cigar like something your cat leaves in the dark corner of your closet; J.D., reeling from sealers and his choice of refreshment; and finally, Ol’ Fred, struggling a cooler and wearing a four-day beard and a floppy white hat stained with diesel grease and fish blood. We congregate don my front porch, and the dark rum drinks went around and the sun began its long western slide and we ate fish and grits and fresh tomatoes and the clapper rails cackled when the tide changed directions at sundown.

There’s a saying in these parts, uttered as gravely as a discussion of the last hurricane or full moon flood tide. “It got drunk up around here real bad last night.” When the sun came up, there was Beek and Howie and Fred in comfortable corners and J.D. tethered to the porch railing to keep him from tumbling off into the ticks, chiggers and copperheads.

And Ol’ Fred’s floppy white hat was perched atop a sweating marine battery. I rescued it, turned it over and read the label. “The Tilley Hat. Guaranteed for life, insured against loss. Made with Canadian Persnicketiness. It floats, repels rain, blocks UV rays and won’t shrink.”

But battery acid? In these days of conditional guarantees, this seemed unconditional enough. But Ol’ Fred wasn’t concerned with warranties. All he wanted was something to keep the sun off his nose and ears, already worse for the wear from his time over the Betsy Ross. He slapped it back on his head and the boys got back on the boat and headed on up to Beaufort on South Carolina’s stretch of Intercoastal Waterway. And I set out to get me a Tilley Hat.

And I did. I thought I looked pretty snappy — khaki shirt, khaki shorts, Tilley hat and dark polarized shades. My neighbor called me a strolling, drawling Panama Jack poster. That was on a good day. Later, he said I looked vaguely pompous. Another said, “Some woman must have give you that fancy hat.”

But it wasn’t a woman. I bought it myself because I was raised with a hat on my head.

Blame it on Capum Roger, Roger Pinckney the 10th, the Old Man, my daddy, river man, dock builder and county coroner for 36 years. Being coroner did not have much to do with hats, except when he took his off out of respect for a corpse with which he had been recently acquainted. But being a river man sure did. Back when I was Nehi, I tagged along on his various expeditions, to Hilton Head, Daufuskie, Low Bottom and Barrel Landing, back before the islands in our part of the world had bridges. “You ready to go, son?” I’d dance around like a spaniel. “Yessir, yessir.” Then he would look at me like I was a horse we was getting ready to buy. “Well, where’s your hat?”

There were generally several candidates among the beat up, hand-me-down gimme caps advertising Robin Hood Flour, Dixie Cola, Dixie Crystals Pure Cane Sugar, and the14th Annual Picnic of the First Pentecostal Church of the Sanctified Brethren in Hardeeville, South Carolina. I’d choose one at random, slap it on my head, and the Old Man would nod and smile and we were ready to hit the river.

I got my first really good hat about the time I got my first outboard motor. Before the motor there were oars and a cypress bateau cleverly designed with high transom and deep skeg and no place where a motor might fit. But eventually there was a 16-foot Yellow Jacket molded plywood skiff and a wheezy eighteen Evinrude Fastwin with a distinctly unpleasant noise in the lower unit.

We called it “Bumblebee.” And it stung too, when you ran it in the rain and the magneto leaked juice out into the tiller. But in dry weather, you could take it offshore and troll for mackerel and blues till the pines along the beach lay on the horizon like a fine green smudge. You could auger through pluff mud and sand and jump a shell rake or two and ball the propeller up with ropy marsh grass, and if you had a handful of shear pins and a pair of channel locks and maybe a spare sparkplug and an emery board for the points, Bumblebee would always get you home.

We called it “Bumblebee.” And it stung too, when you ran it in the rain and the magneto leaked juice out into the tiller. But in dry weather, you could take it offshore and troll for mackerel and blues till the pines along the beach lay on the horizon like a fine green smudge. You could auger through pluff mud and sand and jump a shell rake or two and ball the propeller up with ropy marsh grass, and if you had a handful of shear pins and a pair of channel locks and maybe a spare sparkplug and an emery board for the points, Bumblebee would always get you home.

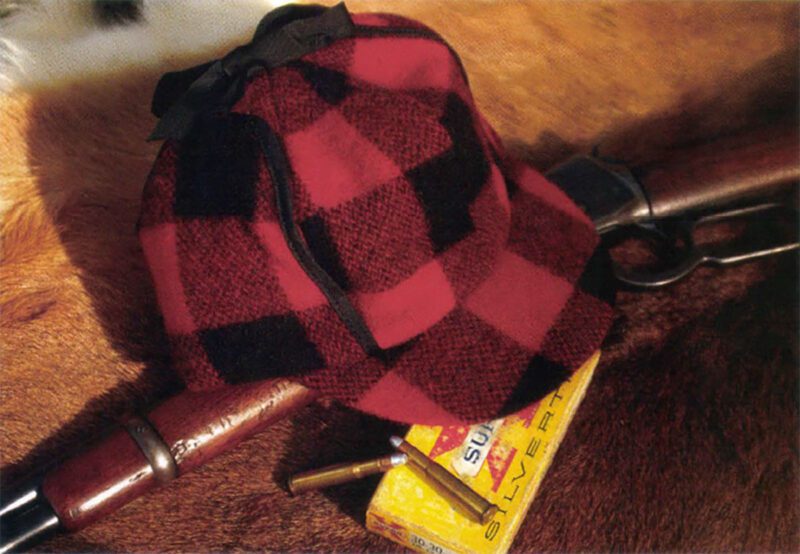

And the hat? It was special enough to make you lay up nights and thumb catalogs and covet and lust like they were stained and wrinkled back issues of Playboy — a gen-you-wine L.L. Bean Allagash. I had an Iver Johnson 16-gauge Nitro Proof Special — 30-inch barrel, stove bolt through the stock, with a bad bark and worse bite. It was early spring, the deer season was closed and there weren’t enough quail to bother with and I took the old thunderstick on a one-way ride to Blue Channel Gun and Pawn. The entire proceeds went to a U.S. Postal Money Order which I breathlessly sent off to L.L. Bean, Freeport, Maine.

It was a long time coming. It seemed so, anyway. But one day the mailman plopped a lovely and perfectly square box upon the porch and I tore it open and there it was, distinctively blocked, one brim snapped to the crown to clear the gunsights in the best Aussie style, and — lordy — a mosquito net neatly folded inside. That Allagash hat would one day fan fires and water dogs, but was initially treated with extreme respect. It was a full two weeks before a gust blew it overboard.

It floated. My fishing buddies, out of jealously I suspect, hollered, “Even the river won’t have it!” But they turned the boat back around, so I could fish it out and wring it out and put it back where it belonged.

My poor and long-suffering mother, thinking such headgear was inappropriate for a young man duty-bound for responsible citizenship, threw it atop a cage containing my brother’s pet gray squirrel. That squirrel and I differed in a broad range of opinions, but shared one. We did not like each other. Loose and amok in the yard, it would run the clothesline, stopping to gnaw upon collars and carefully urinate on each of my shirts. He got his just desserts the following year, when he attempted to raid a neighbor’s pecan trees. But by then, it was too late. The squirrel had chewed the salt-sweat headband from my treasured Allagash.

But I wore it anyway. I wore it to Gale Break, where the wind whistled and the spottails hit cut mullet in the fall in the rumbling flood tide surf. I wore it in the rain down in a Pritchard’s Island canebrake, where I took my first wild pig, a 100-pounder with number one buck from another16 at 20 yards. I wore it in the Bay Point brush, when I sat down on a cactus while awaiting a buck that would not come. I wore it limping all the way back to camp, where I hung a blanket across a corner and wore my hat but not my pants and extracted every deep-driven spine in the light of a quavering and hissing Coleman. I wore it over on St. Phillips, where I got lost looking for a pond and shot two moccasins instead of scaup.

Then it blew off the second time, and heavy with mud and dirt and sweat and memories, it did not float. The river got another chance and it took it, and I had to run 15 miles of water with a bare head and a broken heart.

I got my first Stetson when I got my first horse, a fine gray Arabian gelding. The horse was a product of prostitution, almost. Joanie was a long-legged blonde thing, a pool-shooting, get drunk and lay down on the barroom floor and leg wrestle the boys for 20-dollar bills kind of gal. Working diligently for five years, she sent two men to the chiropractor, three to counseling, one to rehab. Then she got around to me. She had a string of horses and couldn’t pay the rent and went off to a job in the city and left the horses in my keeping. Come spring, she owed me a thousand bucks and we drank Tennessee sour mash and dickered over swapping the gelding for part of the bill until we crawled off to bed and I got the gal and the horse but not the money. And that’s the only time I ever prostituted myself, which is a fine thing for a writer to be able to say.

I got my first Stetson when I got my first horse, a fine gray Arabian gelding. The horse was a product of prostitution, almost. Joanie was a long-legged blonde thing, a pool-shooting, get drunk and lay down on the barroom floor and leg wrestle the boys for 20-dollar bills kind of gal. Working diligently for five years, she sent two men to the chiropractor, three to counseling, one to rehab. Then she got around to me. She had a string of horses and couldn’t pay the rent and went off to a job in the city and left the horses in my keeping. Come spring, she owed me a thousand bucks and we drank Tennessee sour mash and dickered over swapping the gelding for part of the bill until we crawled off to bed and I got the gal and the horse but not the money. And that’s the only time I ever prostituted myself, which is a fine thing for a writer to be able to say.

The Stetson was an El Presidente, muted mist grey, with a glorious four-inch overhang and a crown that held about nine and a half gallons. It shed sun, rain, dust, and the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, as the bard so aptly put it.

It was an icon. Hell, I was an icon — a man on a white horse who could tip his Stetson to the ladies. I kept wearing that Stetson and fooling with horses and tipping my hat till I got three fine daughters and two sons that all got raised on horseback. And I got more than children. I got one of those spring-loaded gizmos to hold the Stetson up on my pickup’s headliner, where it looked better thana gunrack full of lever actions.

But there was scant profit in being an icon. I went into the training and boarding business, fooling with other people’s horses even if I did not have enough trouble with my own. They say you can only train a horse if you know more than the horse, and I set out to test that adage on a stallion which loved me with tooth and hoof and all the intensity a horse can muster. I wanted him a stallion while he grew in style and neck and girth and planned on leaving him that way until I could no longer endure his horsey affection. I reached that point entirely without warning, halfway through a tag-alder brush pile. He was headed north by northwest at a lively clip, wearing a halter with rope attached. I was to the south-southeast at the other end of the rope. It was tangled, accidentally, but nevertheless quite securely, around the majority of my right hand.

Old John B. Stetson, who got a hundred-dollar grubstake and started making hats back in 1865, would have been mighty proud of the dust I raised. So would Gabby Hayes. I got loose, after about 40 yards and enough inspired verbal inflection to put a fine blue tint on the surrounding air. I picked myself up first, then reached for the Stetson, but my hand did not work anymore. I popped a cool one, then two, and drove myself to the hospital.

Singlehanded.

The doctor did the best he could with the shattered bones. A dozen years later, two of my fingers still point in inconvenient directions. Thankfully, my trigger finger was spared. And the rest? Well, I manage. Just don’t ask me to make change in a hurry or come up with a quick obscene gesture.

When I became a man, the Good Book says, I put away my childish things. So I don’t ride much anymore. Horses are taller than they used to be and the ground harder with each passing year. But I still have the Stetson. Cleaned, steamed, blocked, and somewhat stained and battered, it hangs from the long left brow tine of a 146-point rack I took way up in northern Minnesota. Someday, I may ride the Colorado high country after elk or mule deer. The Stetson awaits.

Other hats await, too. Hats I will someday own. I don’t read the girly magazines any longer, but I’m still dog-earing and sweating up the catalogs. Like Langenberg’s, America’s oldest hat company, 20 pages of Stetson lookalikes, Aussie bush hats and old-timey billed caps with insulated ear flaps like Elmer Fudd wore unsuccessfully chasing Bugs Bunny. Don’t think only Elmer and Grumpy Old Men wear them. I saw lots of ’em, back when I was treading on thin ice and dangling lures up in Minnesota, where old men drank peppermint schnapps and made modern art with tobacco juice and stood around hopefully eyeing bobbers and saying “ya shoore, dat was a big one you caught here last year you betcha.”

And then there’s Filson. C.C. Filson began supplying Klondike-bound gold rushers with coats and blankets from his Seattle factory back in 1897, with a credo to build every garment like a life depended on the quality and for where those miners were headed, it quite often did. Filson has earned a well-deserved reputation of toughness, culminating an advertising campaign that featured a 1600-cc Volkswagen engine in one of their packs. Filson says “you might as well have the best” and you might as well, especially if it’s a Filson hat, since you only have one head, even if you — like me — rarely use it to its full capacity. Right now, it’s locked up as tight as a laptop trying to download a quick-time video. Call it sensory overload — three weights, four colors. And that’s just the legendary Packer, sure candidate for a future fan-the-fire and water-the-dog favorite. Then there’s the heart-throbbing Bush Hat, leather hatband and chin strap, two colors, two weights.

And then there’s Filson. C.C. Filson began supplying Klondike-bound gold rushers with coats and blankets from his Seattle factory back in 1897, with a credo to build every garment like a life depended on the quality and for where those miners were headed, it quite often did. Filson has earned a well-deserved reputation of toughness, culminating an advertising campaign that featured a 1600-cc Volkswagen engine in one of their packs. Filson says “you might as well have the best” and you might as well, especially if it’s a Filson hat, since you only have one head, even if you — like me — rarely use it to its full capacity. Right now, it’s locked up as tight as a laptop trying to download a quick-time video. Call it sensory overload — three weights, four colors. And that’s just the legendary Packer, sure candidate for a future fan-the-fire and water-the-dog favorite. Then there’s the heart-throbbing Bush Hat, leather hatband and chin strap, two colors, two weights.

But I’ll save the best till last. Not the best hat. Lord help me if I ever have to choose one of them. But the best of me, what some call Golden Years and others call dotage, cannot be avoided, so I have decided to embrace it, elevate it to a folk art, to fine tune it like a hillbilly fiddle. I will whittle me a set of cedar divers. I will take up smoking a pipe. I will swap my Model 12 Winchesters for an L.C. Smith field grade double12. I will buy a McAlister Old Timer Waterfowl Hat, all tan and wonderfully slouchy waxed canvas with a leather pocket on the side for a tuft of tail-feathers. I will set up in the marsh where the great Savannah River dumps into the sea. I will call and shoot scaup and they will wheel and come back again and again. And I will wear my hat and the Old Man will see me and smile.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself. Buy Now

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself. Buy Now