He was a dentist and photography and a storyteller. He was one hell of a baseball player. He was husband and father and perpetual wanderer and a hunter and fisherman who once held fourteen world records for billfish, sharks, dolphin and tuna. He was the great-grandfather of the American Western, spun off now into hundreds of movies and a thousand novels. He was Zane Grey, author of eighty books that sold an astounding 132 million copies. And he made more money from just one title than Ernest Hemingway mad his entire lifetime.

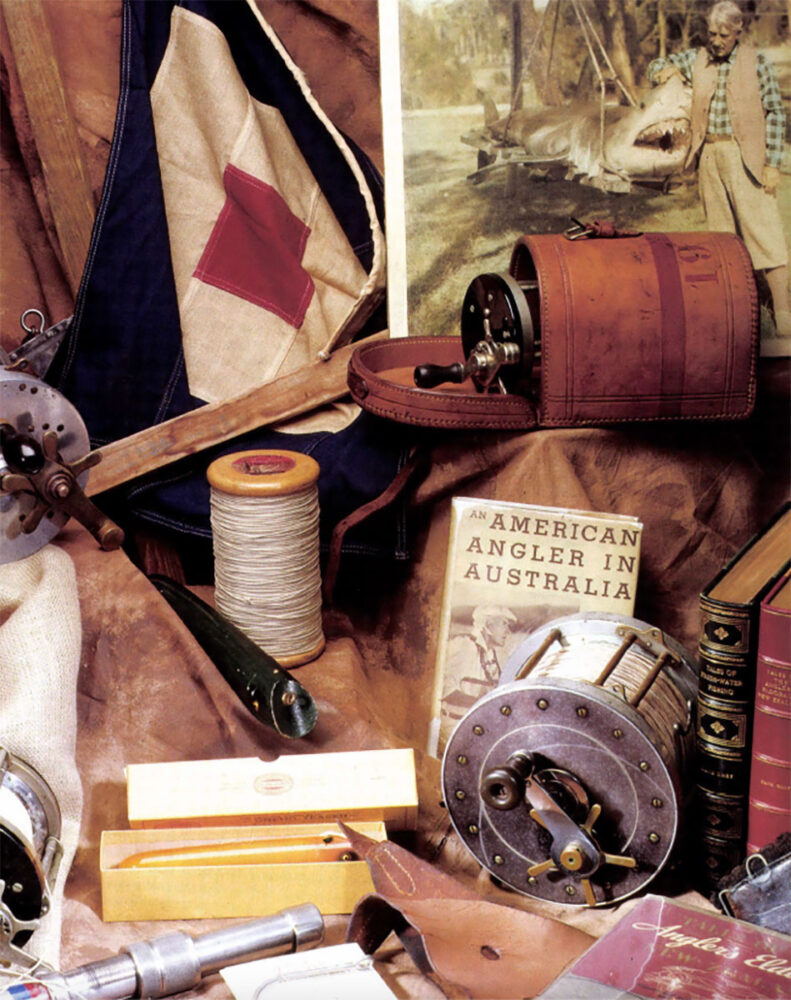

Tackle and other fishing paraphernalia owned by Zane Grey were exhibited at the International Game and Fish Association Museum in Florida. Exhibition curator ed Pritchard provided many items for the display.

But first, he wasn’t Zane Grey at all.

Born Pearl Zane Gray, he was the sun of a dentist and part-time preacher, the grandson of pioneers. Young Pearl Gray had a Norman Rockwell childhood on the sleepy, elm-lined streets of Zaneville, Ohio, with the white picker fences, the swishing screen doors and broad front porches of Middle America. He was lean-faced and tow-headed and he grew up on fishing and baseball, going after bass and bluegills and catfish in the Muskingum River with. Cane poles and bobbers, pitching sandlot for his hometown team and later semi-pro for clubs in Ohio and Michigan while earning extra money pulling teeth with this strong right arm.

His curveballs incited fistfights in the stands and riots in the infield and his fastballs blitzed opposing batters, at least until baseball officials moved the mound back nine feet. In 1892 his .375 batting average won him a scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania. When Gray’s father reminded him he could not major in baseball and suggested dentistry as a logical alternative, Pearl gray begrudgingly complied. Gray played college ball during the school year and semi-pro summertimes, but under various aliases to keep his scholarship in place.

After graduation, Gray set up a practice in New York City. For six years he unhappily chilled and filled and pulled while he worked nights to tum his grandmother’s pioneer journal into a novel. When nobody would buy Betty Zane, he printed it himself in 1904. He married Lina “Dolly” Roth a year later. It would be a long, if contentious, marriage. Dolly would bear him two sons and a daughter and through bliss, separation and joyful reunion, she would always encourage him to think of his writing first.

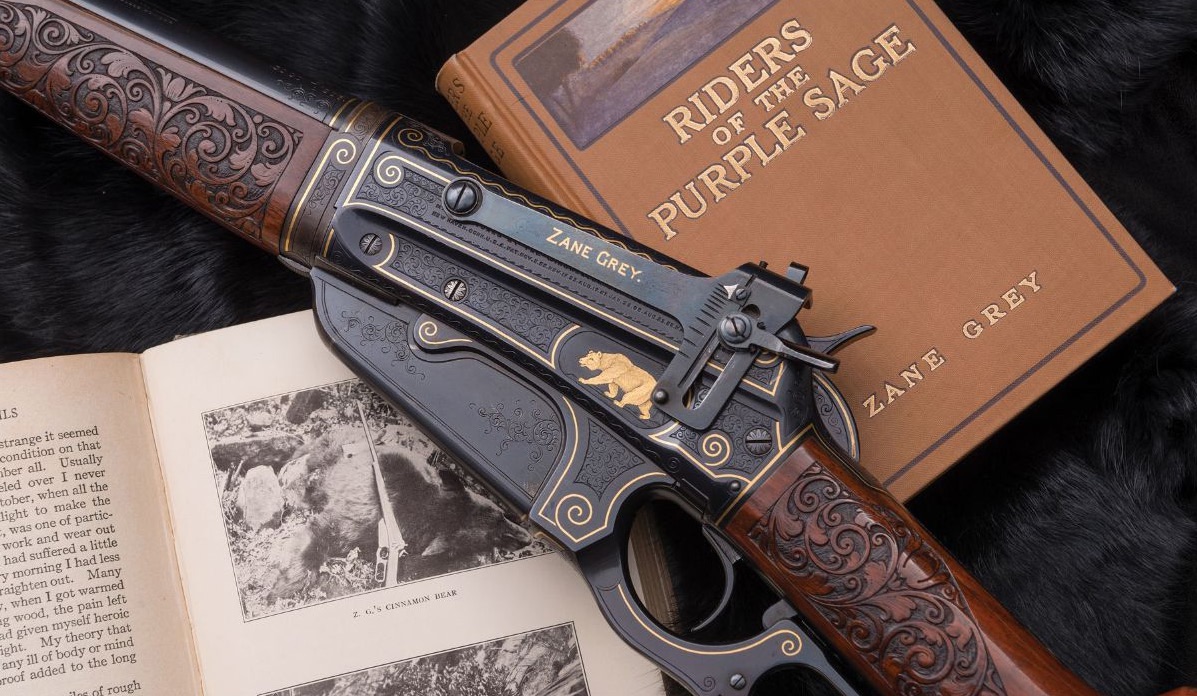

In 1905 he took Dolly’s advice and gave up dentistry for the literary life. By then he was Zane Grey, dropping his first name for his middle, changing the a to an e, and producing his first fishing stories for Field and Stream. He wrote another novel to scant acclaim and another that did a little better. But in 1912, when he was broke and about to go back pulling teeth, Harpers bought Riders of the Purple Sage.

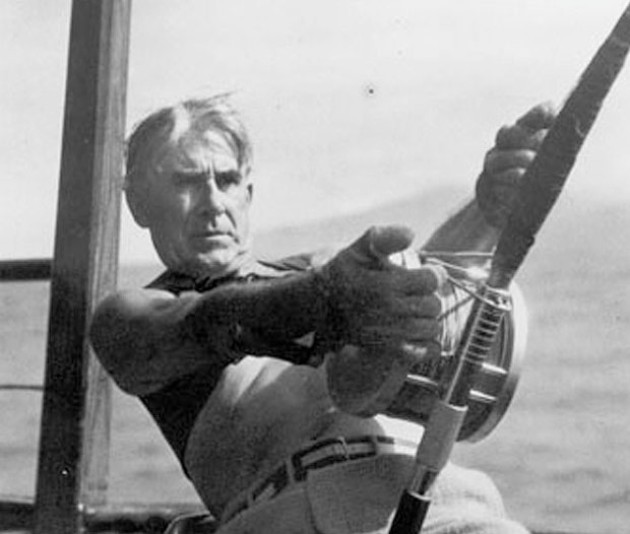

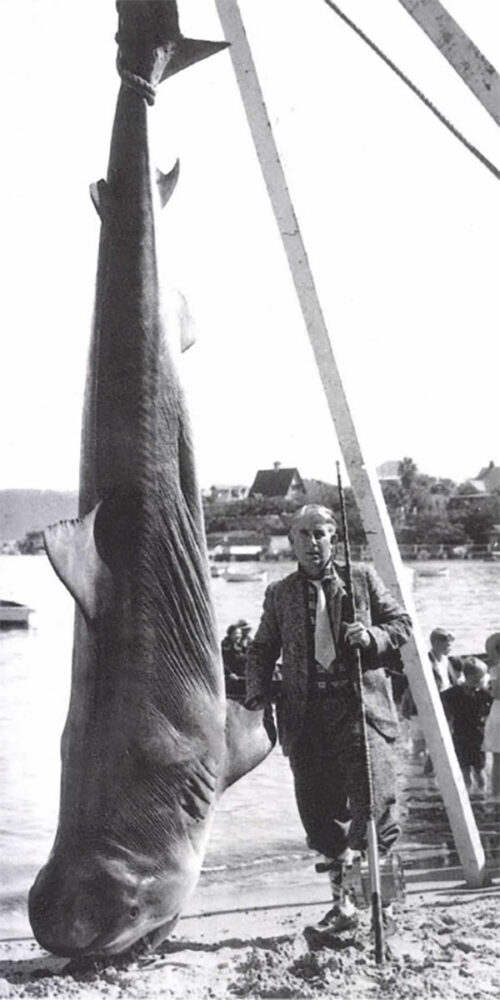

Grey caught this world record, 7,036-pound tiger shark on an expedition to Australia.

These were the days when America was becoming a world power. We had dusted the Spanish over Cuba, put down a guerrilla insurgency in the Philippines, annexed Hawaii and Puerto Rico, and were building the Panama Canal. But five scant years before America lurched into the Great War, we were also taking a long, wistful look backwards. Crazy Horse and Custer were dead. Sitting Bull had become a sideshow attraction, and the stretch of steel rails and barbed wire had forever put an end to the Old West. Theodore Roosevelt was our cowboy president and Buffalo Bill was giving America an eyeful of stampeding buffalo, whooping Indians and steely eyed gunslingers.

Riders of the Purrple Sage was the right book at the right time, a classic tale of a mysterious stranger who helps a beautiful young woman keep her ranch. It sold three million copies, was filmed three times and launched Zane Grey on an 80-book, 25 year literary career, the likes of which was not seen again until Stephen King began racking up best-sellers in the 1980s. Grey moved to California, began collaborating with Hollywood and churning out such titles as The Long Star Ranger, The Mysterious Rider and The Thundering Herd. By the Roaring Twenties, Grey was making a half-million dollars a year.

Zane Grey might have outgrown baseball, but never fishing. Terry Brykeznski, in his introduction to Grey’s Rivers of the Everglades, writes, “You might think he could afford the best tackle engineers could design, the world’s ultra-exotic fishing holes to dip a line and the most lavishly equipped yachts to transport him there. He could and he did.”

Grey fished western rivers, the Everglades, the Florida Keys, the Gulf of Mexico and the royal blue waters off Catalina Island. When he wrote of catching seven marlin in a day, the last a record 328-pounder — which repeatedly tried to jump in the cockpit — and then of boating 22 tuna, Robert Davis of Munsey’s Magazine took exception. ”You write ‘the hard fight of a tuna liberates the brute instincts in a man.’ Well,” Davis quipped, “it also liberates the qualities of a liar.” At his invitation, Davis went out to see for himself. When Grey admired a jaunty feather run into the brim of his editor’s hat, Davis replied, ”What you need for your hat is a head.”

On a 1924 jaunt to Liverpool, Grey came across a three-masted schooner, Marshal Foch. He bought the ship for $17,000, renamed it Fisherman and spent another 40 grand outfitting her for long ocean voyages. There were four Fairbanks-Morse propulsion engines, auxiliary generators, a crane for hoisting huge gamefish, a photographic darkroom, machine and blacksmith shops, staterooms, salons, a gourmet-ready galley with a Japanese cook and three fishing launches ready on the main deck. Grey sent his crew sailing toward the Panama Canal, with stops in Nova Scotia and Jamaica.

It was an arduous voyage. Fisherman peeled her keel on a Caribbean reef and the crew had to drive off piratical natives with rifles while waiting for the tide to float her free. After laying up for repairs in Panama, and making it safely through the canal, Grey came aboard and headed for Cocos, the setting for Stevenson’s Treasure Island, where marauding sharks cut off nearly every tuna before they could be boated. Then it was on to the Galapagos where a storm nearly swamped his schooner.

The photograph in this lGFA exhibit shows the author with the great white shark he caught just before his death in 1937.

Grey did not make it Tahiti that year. Unnerved by the storm, he turned east to the fishing grounds off Mexico, setting world records with a 318-pound yellowfin tuna and a 132-pound Pacific sailfish, which he bettered a week later by three pounds. Grey put ashore for much-needed rest at Zihuantanejo and Cabo San Lucas, then returned to California, settling his sea nerves with a long fishing trip in Oregon’s Rogue River country.

But meanwhile, there was trouble at home. Back then, few things excited female lust more than a successful literary or movie career and Grey used his status as America’s best known writer to full advantage. Early in his western ramblings, Grey had run across renegade Mormons, still practicing polygamy after Utah banned the practice as a prerequisite to statehood in 1896. These Mormon elders were deeply moral men, ordained by God, they believed, for more than one woman. Grey figured to get in on it, too. As early as 1911 he began taking young women on his hunting and fishing trips. There was Emma, Dorothy, Louise, Mildred and even his wife’s cousins, sisters Lillian and Claire, who took turns warming his sleeping bag, often on the same hip. To members of the press, Grey introduced these women as his nieces or secretaries, but he did not fool Dolly. Left home to raise their children, Dolly chafed under his infidelity. “The Christlike spirit of turning the other cheek,” she wrote, “never manifests itself in the battle of woman against woman….” But ultimately, Dolly accepted it as one of the costs of marriage to a famous man, even advising him on how he could handle jealous snits between “your girls ”

Money was another matter. When the Great Depression wiped out Grey’s stock investments and slashed his royalties by 90 percent, he kept spending. Dolly retaliated by forming the Zane Grey Corporation and putting her husband on salary. Still, he spent, overdrawing his checking account until Dolly wondered how she could afford food for the children.

Grey’s problems with money and women nearly got the best of him in 1933, when he met a young woman who had kept a journal while hitchhiking across the West. Berenice Campbell was 25 and Grey was 61 and, thoroughly smitten once again, he offered to market the journal and pay royalties. When the Story sold and the bone-dry bank sucked up the funds and Grey couldn’t pay, Berenice Campbell sued. And then the IRS smelled blood and dunned him after denying much of his extravagant spending as legitimate business expenses.

Forever flirting with bankruptcy, Zane Grey kept fishing. He finally got to Tahiti in 1926, aboard a steam mail packet on its way to New Zealand. He liked the women and he loved the sea, but Papeetewas just too raucous and sordid. New Zealand, as remote and wild as the West he loved, suited him better. Grey toured the Ulterior, waded mountain streams after rainbow trout and was honored as an ancestral angler by native Maori, most of whom had never seen a fly fisherman before. Offshore, Grey caught sharks, yellowtail and two species of marlin.

Grey went back to California, but came again to Tahiti the following year, buying remote land for a fishing camp, his lack of money notwithstanding. He brought Fisherman, loaded with eight prefabricated buildings, equipment, water, food, launches, hooks, lines, lures and reels custom made by Hardy to his own specifications, but the crew nearly mutinied and sold the goods to the highest bidder when their pay came late. Grey unloaded the supplies, sold Fisherman to a wealthy Tahitian to cover his debts, but promptly purchased a motor sailer that proved even more expensive. Kallisto, rechristened Fisherman II, cost him an initial $40,000, another $300,000 to refit and $5,000 every month thereafter. But still, Grey kept on fishing, racking up a long string of world records: a 53-pound dolphin, a sailfish at 170 pounds, striped marlin at 450, a silver marlin at 710, beating his own record with another dolphin at 64 and finally a 1,040-pound blue marlin that took him seven hours to land.

Grey hefts a 35-pound bonita which he used as bait for catching thousand-pound marlin in New Zealand.

Beset by continuing financial shortfalls, Grey cancelled plans to sail Fisherman II around the world, sold the ship at a loss, then bought yet another boat, this one custom built in New Zealand. Frangipani, a 48-foot motor yacht, was ill-suited for the open sea, but Grey hired a crew to take her to Tahiti, 2,400 miles north and west, the first time a motor yacht had made that voyage.

Grey met the boat in Tahiti. But there is something about Tahiti. Run there and you will like it enough to stop running and what you are running from will soon catch up with you. Zane Grey holed up in his seaside bungalow, wrote when he wasn’t fishing, but he suffered continuing financial woes, deep depression and a plague of fleas riding upon the backs of ubiquitous island rats. Despite the flea bites and his black moods, Grey produced Tales of Tahitian Waters, an immediate non-fiction hit, and The Reef Girl, a novel so salacious it was unpublishable until 40 years after his death.

In 1936, the man who had written books made into movies, decided to make his own. The Zane Grey Corporation hired a film crew to document shark fishing off Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. He invited Ernest Hemingway to join him, but America’s second best known outdoor writer was fishing off Bimini and declined.

Hemingway, who coveted a world record but never got one, should have come. Grey tied into another record off Sidney, a 1,036-pound tiger shark. He boated it after a two-hour battle and used the footage in White Death, the story of a village terrorized by sharks, and saved by a mysterious, wandering fisherman. It was a plot right out of his westerns, but it did not fare well in theaters.

Back in America in 1937 and fishing steelhead on Oregon’s North Umpqua River, Grey was felled by a massive stroke. His companions rushed him to a local hospital where he regained his speech, then to Los Angeles where he slowly recovered use of his limbs. He walked, worked out on a rowing machine, and by the following year felt fit enough for another Australian adventure.

But Zane Grey would never be the same. He tottered around Sidney, shyly accepting the adulation of his many Australian fans. In a feeble attempt to fish the harbor, Grey hooked one fish too many — an 831-pound great white. The fight probably weakened his heart and provoked the inevitable. Grey returned to California to begin writing an autobiography and got as far as his first year at dental school when a massive second stroke killed him on October 23, 1939. He was 67.

So what can we say of Zane Grey, this dentist turned novelist turned outdoor writer? His novels created a romantic vision of the Old West, still widely accepted to this day. He held more world fishing records than any man in his time. His global exploits popularized big game fishing. The demands he made on his equipment created a revolution in tackle and reel design.

But what about his art? Sometimes Grey’s writing is crisp and clear, as when he tells of a pack of sharks chasing a hooked billfish around his boat in his 1918 Tales of the Fishes. Grey wrote, “…the sailfish sheered around on the surface, with tail and bill out, while the shark swam about five feet under him. He was a shovel-nosed, big-finned yellow shark, weighing about 500 pounds. He saw me, I waved my hat at him and he did not mind that.” But a Few pages later, when a pair of flying fish whizzed by his head, he wrote, “They had been pursued by some hungry devil of a fish, and with a birdlike swiftness with which Nature had endowed them, they had escaped the enemy.”

You may stumble, but Grey always picks you up again and rambles along about everything that catches his eye — the jellyfish and the minnows and the birds, the way the light hits the water, even the stomach contents of the gamefish he kills. In the end, his wisdom and relentless enthusiasm wear you down and you say an unknown writer might not be able to sell this to Field and Stream today, but it’s one hell of a story, anyway. Little wonder 40-odd of his titles are still in print.

Grey’s Tales of Fishing Virgin Seas, reprinted by Derrydale Press in 2000, was named by The Los Angeles Times as one of the best non-fiction titles that year. Virgin Seas is one of 12 Derrydale reprints released over the last five years at about 2,500 copies per cover.

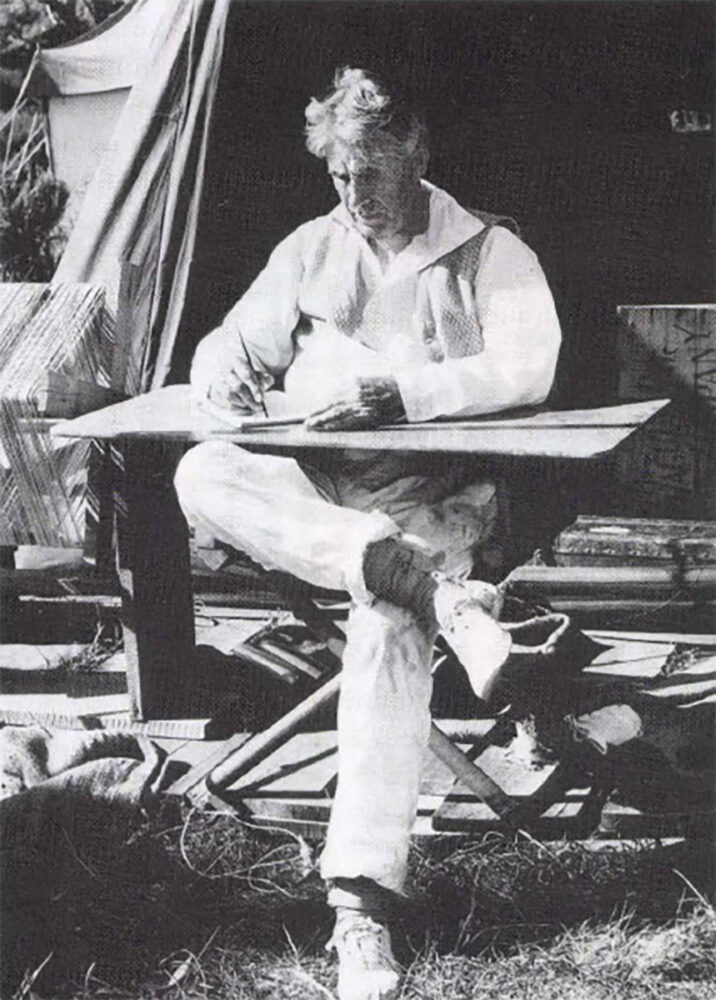

Zane Grey works on a manuscript during his 1926 expedition to Australia.

Derrydale’s Kim Leslie pegs the astonishing revival on the public’s increased interest in sportfishing, and the decline in fish stocks worldwide. “Zane Grey literally fished virgin seas. He battled thousand-pound sharks in the Pacific. Today you are not likely to see anything half that big. People like to read about the way it was.”

But maybe Grey’s greatest legacy is not literary at all. Through good writing and bad, he decried the plight of Native Americans long before it became fashionable. Grey correctly pegged the automobile and attendant highways as the ruination of the wilderness. He foresaw the decline in numbers and sizes of gamefish from commercial harvesting and from “sportsmen” killing every fish they caught. He was an early proponent of catch-and-release and opposed the sacrifice of natural resources during national emergencies — in his days, the netting and grinding of albacore into fishmeal fertilizer during WWI. But he knew he was a prophet without honor. “A good rule of angling philosophy,” he wrote in 1918, “is not to interfere with any fisherman’s peculiar ways of being happy, unless you want to be hated. It is not easy to influence a majority of men in the interests of conservation.”

But he tried and eventually did. Perhaps that is Zane Grey’s greatest legacy.

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly.

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly.

Though he made his name and his fortune as an author of Western novels, Zane Grey’s best writing has to do with fishing. There he was free from the conventions of the Western genre and the expectations of the market, and he was able to blend his talent for narrative with his keen eye for detail and humor, much of it self-deprecating, into books and articles that are both informative and exciting. Buy Now