“Wouldn’t it be great?” Kjos said again, his blood up, completely dismissing the ducks, “To have a permanent puppy, to have first love over and over again?”

The sun slept in that years-ago Utah morning over the Salt Lake marshes. Where Kjos and I were guests in an ancient ducking tradition, the province of several old fraternities that preserve the religion there.

I had thought the old ducking clubs to be largely the bishopric of the Eastern Shores. ’Twern’t true. In the Intermountain West, they carry on devoutly as well, in weather-beaten, old clapboard cathedrals of their own.

After an amicable dining the evening before in one of the most venerable, talking of days and guns, ducks and dogs—logs ablaze, a Chessie and a Lab lazing hearth-sides of the great fireplace, others by their masters’ chairs beneath the electric hum of hunting palaver, coveted brass blind tags being pulled from a 123-year-old wishing board—we were happily midst the congregation.

“Baptized first in the Blood, and second, from a duck boat,” as Nash Buckingham said of Irma Witt, I recall.

Now, with the next morning’s waking over the vast backwater holding of that same house of devotion, dogs shivering eagerly alongside, we waited in the gloam for the scant, thrilling minutes to shooting time and first wings. Anticipation dripping like freshening raindrops onto the parched landscape of four unquenchable waterfowling hearts.

For good reason.

“Waterfowl livened the sky, the clap of their wings like thunder,” John Fremont reported of the Salt Lake flats on a blustery day in 1843. On certain days they still do. Maybe not like then, but more than you can remember “when.” We had hunted a stilt blind over open water the morning of the day before, returning to the lodge at 9:30, heavily laden with our bag. Nine species of birds, including pintails, ruddies, redheads and cinnamon teal.

This morning, we hoped, might dawn as well.

The air was brittle cold, as if it would break, stung like mischief when you took a full breath. A stout northwest wind bored chilblain-deep into the thick layers of oilskin and wool that struggled to shield our core. Were it not for the stacks of flap-jacks, nests of eggs, smoked slabs of bacon and ham, platters of buttered biscuits slavered with molasses, the parting few minutes with our rumps to the fire that kept the inner coals a’simmer, our small hide would have lapsed frigidly unfair. Unfit for habitation. But, of course, for the afflicted of us obsessed with unfit habitation.

Blue-white with first light lay the lonely marsh, as distantly as the eyes could carry…the dry stalks of the bulrush stiff and dry, rattling with the itinerant gusts, the bent and huddled salt grasses hoary with rime.

Butterfly Dance—Golden Retriever by John Aldrich

It had taken a spell to clear the ice from our single, open pothole, to chip out the thick slabs and slide them under another, and then with freezing hands to cast the blocks in ordered formation. Though now they bobbed and yawed, in seemingly undeniable dis-symmetry, with what loomed a virtual invitation.

Though, when the clock clicked to the witching hour, but for birds distantly passing, the clabbered sky stood empty. Still, by 8:30, remaining that way. Hail and hail again, and only the wind to answer. Intensity waned, and even the riveted attention of the dogs gradually lagged, as we sat the guns by. Keeping one eye casually open, but talking of this and that. Somehow landing on the affecting subject of puppies, and all the inherent, joyful little wonders and blessings of puppydom. That you’d like to keep forever, but can’t.

Like lying in fallen red leaves in fall, and having one ’bout seven weeks old crawl up face-to-face, look at you cross-eyed and kiss you on the nose. Or backup-and-spin gleefully, in a spontaneous ring-around. Or growl and worry at your pant’s leg like one day he’s gonna grow up ferocious. Or squat ’fore you know it, carrying the paint-roller you threw, rolling his eyes up innocently, while he puddles on Mama’s new hardwood floor.

And I guess a lot of finely notionable ideas are born in the twixt-times, in the empty hours that sidle along in an idle duck blind. However wishful sometimes they might be.

Because Kjos came up with a pearl-bangled Billy!

“What if,” he said, “we could breed the perpetual puppy?

“That’d be born a puppy,” he mused, with a gleam in his eyes, “and always be a puppy.”

So that we forgot about ducks for a while, investing in the subject, and the Labs perked up too, like they had money in it.

Suddenly it loomed the best intention since chocolate ice cream…the coolest thing, even, since the early Egyptians manufactured air conditioning…and a whole lot happier.

“Yeah,” I wholly agreed, “so there’d never be a shortage of pupper breath or four little paws gallopin’ ’round the house. Or somebody underfoot to grab onto your boot laces, or chew up the arms on your easy chair, or to wade with you and chase water spiders in the creek, and retrieve old boots, or, sometimes when you ain’t lookin’, the brand new ones your wife gave you for your birthday from L.L. Bean.”

“Or to chew holes in the bed sheets,” Kjos exclaimed, “or rip up your used cereal boxes and toilet paper rollers, and chase the damn cat out o’ the house. Who’d do that?” he asked desperately.

“Or serenade you from his crate at midnight,” I declared, “so you’ll finally give up, and he could crawl in bed with you, and park there with a snuggle-claim on Mama, when on a wooden morning you’d like to get to her yourself, or sit with surrendering religious eyes, when you pick him up like a fat little Buddha in your palm, his little thing top his round little belly.”

“Or curl up in your lap sound asleep,” Kjos said, “and twitch and whimper and dream.”

“Better yet,” I suggested, “who’d snuggle in against your cheek on the couch, all soft and cuddly, when you know that’s where he wants to be…the only place he wants to be, and where he’ll always wanna be…more than anywhere else on earth. Twitchin’ and dreamin’.

“What about that?”

Kjos lapsed dreamy-eyed. “Yeah,” he said. Like he’uz talkin’ to a sweetheart.

Then, all of a once, I squinted impulsively and cocked my head, pursing my lips. ’Cause an errant thought troubled my mind.

“Wait though…if he’s always seven weeks,” I said, “you’d never get to see his first, true nose-point on his first found bird, or his first real water retrieve for serious, or get to watch him run a perfect “T” the first time. Or get to teach him how lovely wings are. And he’d never get old enough to go hunting with you for real. You’d not get to see him begin to come into his own at about twenty-four weeks, or put two and two together one day around ten months and come up with four.”

Kjos considered that momentarily.

“Or never see him come to love the gun so much he begs for it,” he added, “or bring back the first pigeon you’d ever shoot for ’im. Or watch him in the field, discoverin’ all the little things about huntin’ the first times, and ever other time like it was the first time. And never shoot wild birds over him for real the first time.”

The conversation died. Moments passed. The Labs looked at us with silent eyes.

Then Kjos sat straight up, like he’uz struck by an epiphany, bumping his head on the blind.

“Then, we’ll just have to make him like Benjamin Button,” he said abruptly, rubbing his head.

“Who?”

“Benjamin Button. You know, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story. Where, come a point in time, it all happens backwards.”

“What the hell does that mean?” I said.

“Well, when he got to be a year old, the reversal gene would kick in. And day by day, he’d gradually go back like he came, and you’d get to enjoy it all…all over again. Just in reverse. And then one day, almost a year later, you’d have the same seven-week-old puppy back again. Because it went by too fast the first time, and you’d thought you’d never have it ag’in.

“And it would happen curiously over and over. Frontwards and backwards ag’in. But never no more than a year could go by in front’ards.”

“And it would happen curiously over and over. Frontwards and backwards ag’in. But never no more than a year could go by in front’ards.”

Moffit’s molars! It shaped the perfect solution, I had to admit. If you’re gonna wish for somethin’, just go on and do it whole damn hawg jowls and collard greens.

We congratulated ourselves a little too jubilantly, while the only birds of the morning—a pair of greenies—sneaked in, buzzing the set, in and out so blistering fast there was no hope of retrieving the guns. While, in the embarrassing era afterward, the Labs looked at us with sour eyes.

“Wouldn’t it be great?” Kjos said again, his blood up, completely dismissing the ducks, “To have a permanent puppy, to have first love over and over again?”

“Wouldn’t it?” I wholeheartedly concurred.

“But you forgot the grandest thing of all,” I said seriously.

He stared at me as an old friend, the question on his face.

“He’d live forever,” I said. “Never grow old, used up and gray. “He’d never have to say ‘Goodbye.’”

For a moment, between us, there was profound peace in that.

Then Kjos sobered, distant for the first time, his face growing ever more somber as the strangeness settled in, and the irony bubbled painfully to fore.

And he stared at me again.

“But I would,” he said sadly.

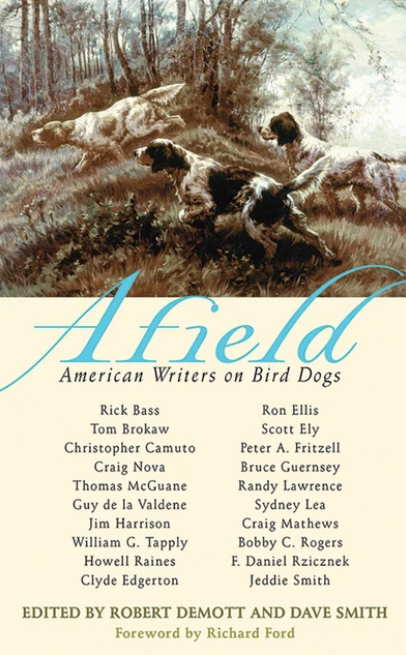

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo, and Chris Camuto, come together in one collection.

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo, and Chris Camuto, come together in one collection.

Hunters and non-hunters alike will recognize in these poignant tales the universal aspects of owning dogs: companionship, triumph, joy, forgiveness, and loss. The hunter’s outdoor spirit meets the writer’s passion for detail in these honest, fresh pieces of storytelling. Here are the days spent on the trail, shotgun in hand with Fido on point—the thrills and memories that fill the hearts of bird hunters. Here is the perfect gift for dog lovers, hunters, and bibliophiles of every makeup. Buy Now