“Woodcock coming your way!” my buddy Jared called out from the doghair aspen.

I immediately turned toward his direction, set my feet for a shot, and looked up, quickly scanning right and left, trying to spot the bird. Nothing showed.

I was on an overgrown trail cleared by some black bear hunters a few years ago in a state forest. I figured the bird came down on the trail somewhere—a typical landing spot for a pushed bird. I backtracked a ways, but nothing flushed. Then I remembered there was a ten-yard-square clearing down the trail a little farther where standing water kept ever-encroaching trees at bay.

I bet he’s there, I thought to myself.

Sure enough, as soon as I stepped foot into the watery clearing the doodle broke cover from the far side and flew straight down the trail. One shot and he was in the bag. And a big adult, at that.

We next pushed into some county land, crossing a small but fast-flowing waterway we dubbed Castaway Creek. In the mud was a large and very fresh print from the hind foot of a black bear. The bears are probably active day and night now, trying to put on weight before hibernation.

Jared went down one trail, fresh cut from the looks of it, while Hunter, my 10-year-old springer, and I went down another, parallel trail. Soon Hunter let out a yelp, a sign he’d struck fresh bird scent on the trail. No sooner did he step into the young aspens to give chase when two woodcock flushed. My shot first sheared off a one-inch aspen, but dropped the bird, too.

We put two ruffed grouse in the bag that day, as well, before calling it quits. Jared’s GPS showed we had hiked 8.6 miles.

Black bears are a common site in Minnesota’s woodcock country.

Jared headed home, but I stayed on at Camp Moose Horn, my 44 acres of wild country in northern Minnesota. The skies cleared that night, and the temperature dipped to a chilly 39 degrees. I was hoping for a frost, though, to drop some more leaves and clear the view for shooting through the thick trees and shrubs.

I awoke about 1:30 a.m., but instead of rolling over, I ventured outside. I’d seen wolves near camp two years ago while scouting for turkeys, but in five years I’ve never heard them howl there. You won’t soon forget their deep, powerful cries and the mystery and fear of the night it invokes. Nothing says “the wild” like a pack of wolves howling in the night from deep within a forest, a bright moon shining overhead.

There was a half moon out, but the only sound I heard that night was a great horned owl hooting in the distance. I went back to bed. There will be more nights at camp to listen for those mournful, spine tingling refrains from Canis lupus.

Wolves are becoming more and more common around grouse camp, but the author still hasn’t heard their distinctive howling there.

I was on the trail and looking for birds by 8 a.m. the next morning. It didn’t take long—after a number of flushes, I realized a flight of woodcock had come in overnight. In two hours Hunter and I flushed as many birds as Jared, myself, and two dogs had encountered the day before in six.

The action was hot; grouse, too. The first doodle broke on the line where a 4-year-old aspen cut meets a tag alder swamp on Camp Moose Horn. The bird hadn’t crested some nearby tall grass before I dropped him.

Hunter and I turned north to a neighbor’s property, where a ruffed grouse eluded a shot after it flushed from a large wood pile. I figure I shot beneath him as the bird flushed low and must have been climbing.

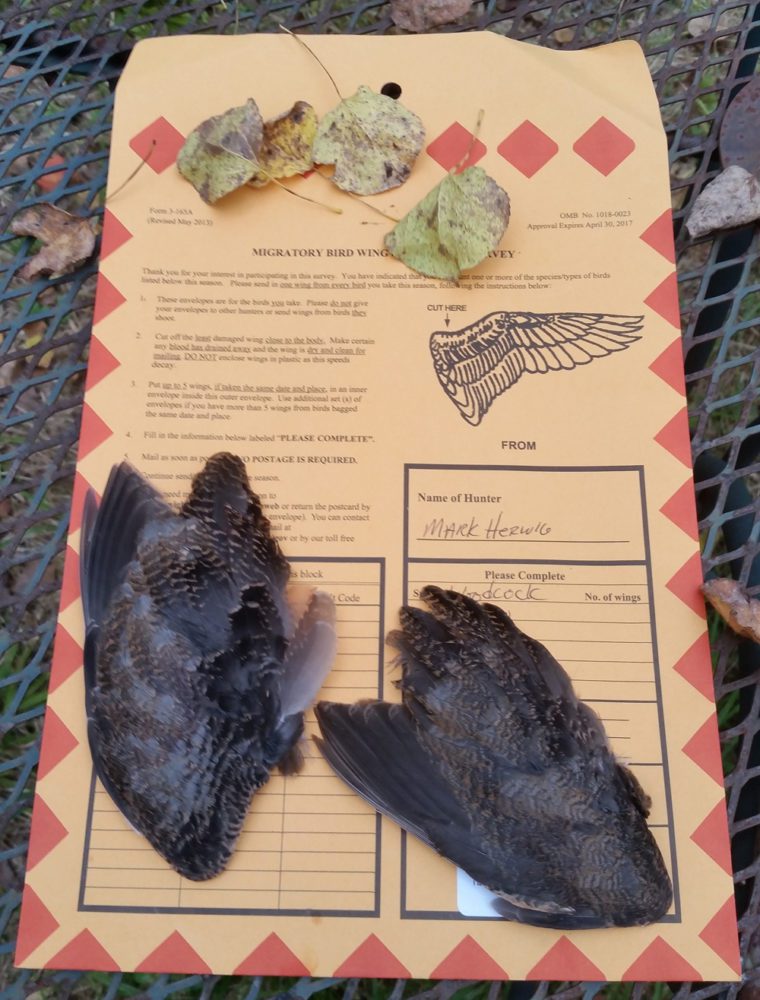

Wing samples help the USFWS monitor woodcock populations.

We moved on, Hunter soon “baying” a bird and cavorting through the woods after more. I left the trail and struck into the doghair aspen. It wasn’t long before a woodcock flushed and, uncharacteristically, charted a straight, slowly climbing course through the trees. It was a long shot, but a good one.

I didn’t want to leave the woods that day because of the fresh influx of woodcock, but it was time to head home. Before leaving, though, I clipped a wing from each of the four woodcock I bagged (two Friday and two Saturday) to send off to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Earlier the Service had sent me some envelopes to mail the wings in for a survey.

To my eye, it looked as if I had three young-of-the-year birds and one adult. That’s great news. It means the hatch was good—a portent of more large in-flights to come before winter sends the woodcock south and the wandering black bears of Carlton County into their forest dens.