The best hunting spots are secrets among friends, where a bird in the bag is just a bonus.

A mist conceals these mountains. They are gray like bone. The sun will not rise above them for another hour, and yet it is eight o’clock. This is a favorite spot. I find woodcock here almost always because this place is so welcoming to them – and to me.

I can see hardwoods rising above me on the steep hills. There is still a touch of fire in their crowns, but it’s fading and soon will be on the valley floor. This is the season I most enjoy.

Today I am here for the woodcock. Other days I am stymied by this plugged-in, computerized world, by its offer of an easy and inauthentic life. It leaves me full of question and second guessing. So I step into these woods. My feet sink into the soft ground. The bog pulls at my boots, rooting me. Here, the worst parts of me fall away, and I become a better version of myself – a man of patience and understanding.

At the base of these hills lies a marsh that is ringed by dead cattails and browned grasses. I imagine a kingdom of ducks within, and their occasional sounds indicate this may be so. I cannot pass through here and remain dry. Despite the dampness of this place and its depth in the valley, there are apple trees. A grouse may fly from their fallen, rotting fruit. Wasps dine there, too, if it’s warm enough.

The earth is too sodden to withstand even a fawn’s tread; this is the earth of the woodcock. They stab it easily with their rapier-beaks, drawing forth their meals. They gather here after flying long nights. Some days I may flush 20 birds if everything is right. Everything is right here more often than anywhere else I know.

I might shoot at a few birds; I might take home two, enough for a meal. I might pass someone on my way out and we will smile at our luck. So much great land has become posted. There are few places to hunt anymore. This place is best kept a secret among friends.

This morning, blessedly, I am alone, except for the raven who finds me always when I step into the woods. To most, he is an ill omen. To me, he is an indicator of certain pleasures: the smell of smoke from the chimneys down valley, rolling hills of crop and woodland, the promise of a shot and maybe a meal. He is my chaperone over colored hills to covers rich with game.

This morning, blessedly, I am alone, except for the raven who finds me always when I step into the woods. To most, he is an ill omen. To me, he is an indicator of certain pleasures: the smell of smoke from the chimneys down valley, rolling hills of crop and woodland, the promise of a shot and maybe a meal. He is my chaperone over colored hills to covers rich with game.

Axel, my dog, is already too far ahead. I am angry with myself; I should have worked him more going into the season. I let him and my anger go. I don’t want to shatter this stillness with my whistle. His wild ranging will cost me birds, I know. And of course, at that thought I see a bird take flight, whirling as woodcock do, too far away to shoot. I don’t care. Everything here is pleasing in the way sleep is, or a great meal or a fine painting on a wall.

The leaves are almost gone from the trees, inviting light. Next time I come here, it will look larger, infinite even, but far less stirring. Even the woodcock will be gone, flown to the places they visit each winter, like elderly couples who move south so not to be undone by the cold. One should feel blue at these certainties. Perhaps I do a little. Mostly, I am content. This is a favorite place and a favorite time. I will not rush its pleasures or ward them off with such thinking. I wait for my dog to run himself out a little. He is still crashing through the yellowing fern. A wren joins me, flitting from tree to tree, its pace irregular in the way I wish mine could be.

Axel’s bell has stopped ringing, but I am too casual. He has already run over four woodcock, never noticing them. He does not believe there are birds here. Why then should I take him seriously?

“Trust the dog,” my friend Tim always admonishes. He says this often when we hunt together. He says this each time a bird blasts from a thicket Axel has circled relentlessly and after I have given up. And Tim is right. The dog will settle in as he always does.

I rush up to meet him. He is rigid with impatience. His tail is not up in the classic pose – this dog has never pointed classically. But it’s clear he is on a bird. When finally it flushes, it does so in exasperation, tired of waiting for us to make up our minds. It is only a dozen yards away and still I miss it badly with both barrels.

“There. We’re even,” I say to the dog. A brook is nattering nearby. I cannot hear Axel’s grumblings because of it. I think of Muttley, the cartoon dog, but thankfully I hear only water over rock.

We are both serious now. Axel has proven that birds exist here, and I have proven that I cannot shoot effectively, even after three and a half years of it. But we approach each thicket with determination; we mean business. I will bump two more birds and Axel will point another before one is idiotic enough to fly into my pattern.

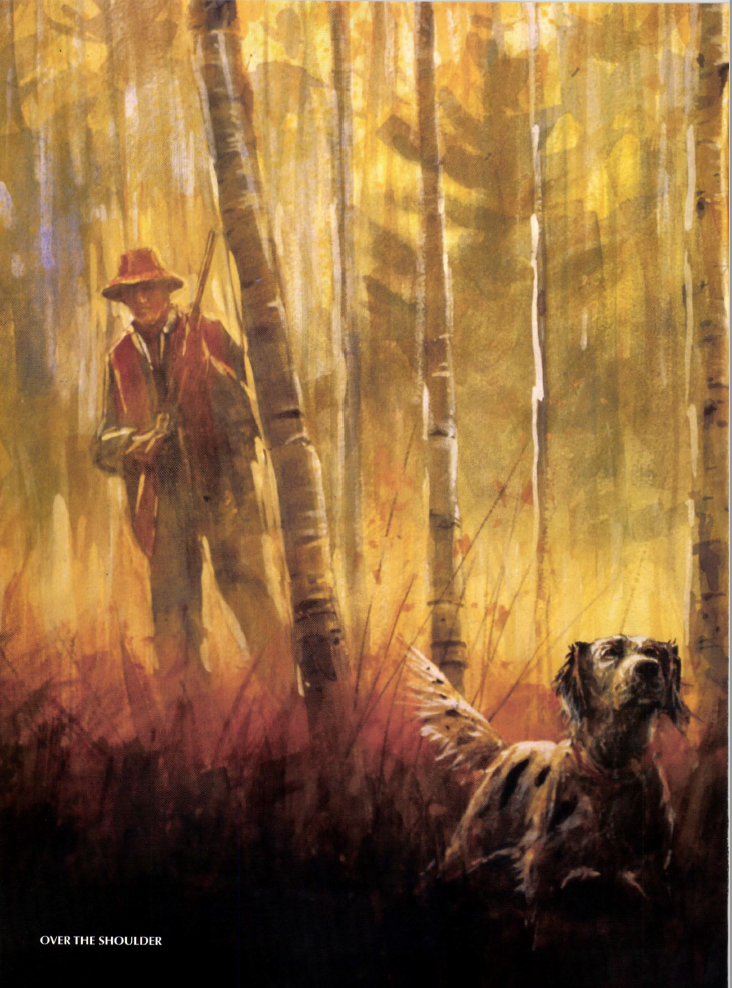

Over the Shoulder by Rod Crossman

Unlike other game, the nobility of woodcock flees at death. The grouse is still King of the Forest, even in a game pouch. Ducks are regal until plucked. The woodcock, madcap and merry in flight, is a sorry corpse, one that seems to have died of some long, slow illness. I throw it quickly into my vest.

I do not want to dwell upon it, but my dog is again out of sight. This is usually no concern, though once again I do not hear his bell.

When I find him, everything falls into place the way dreams do when one is awake, when one can guide them to desirable outcomes. He is locked on a bird in every sense of that word. He cannot be moved. He is the master of his vocation. He is the embodiment of instincts honed by centuries of genetic tinkering. If it can be said that a dog has arrived, then Axel has, if only for a moment.

I step toward him, and the bird erupts gloriously. Axel is steady still. Everything is. The woods are like a photograph. Even the woodcock has slowed enough for me to shoot. Such is the sweetness of the moment that I can control all of it. The bird folds at the shot – of course it does – and before it hits the ground, an entire hunting life in the Vermont woods clacks by in the nickelodeon of my mind. My dogs, my guns, my misses. All of it.

Raven kronks his approval, and I walk over to fetch the bird. Axel is already there. I want to praise him and cannot resist the urge to hug him. He wants no part of it. On one knee, my gun open and on the ground, wrestling with him, trying to get him to sit still, I am struck by the ridiculousness of this moment. I am glad that I am alone.

At that moment I hear a grouse launch, the sound is like shuffling cards. It flies unbothered into perhaps the only clearing here, well within range. I look at my shotgun, just out of reach, inert steel and walnut, and then back at the bird. Still, I have time to watch it weave from sight.

Axel roars after the grouse. I realize, as he slips my hold, that his coat is knotted impossibly with thorn and burdock. I will never be able to brush it clean. It is strange what one thinks of in these moments.

The sun has finally cleared the nearest peak, and I watch the remnant mist curl up the hillside as if sucked away by some unseen breath. It is suddenly hot, and I shed my coat as I walk back to the car.

It is a trying game I play now with my dog; I call him, and he runs off. I know it’s not disobedience. He wants to hunt; he gets to so infrequently. What he does not understand is that my limit is filled; I do not want to kill another bird today. There is no reason I should. Tomorrow, I can return with both my dogs and watch them circle me like dervishes, nosing furiously at the tangles of thorn. I can watch the sun strain to illuminate this patch of wood. And if I want, I can shoot another woodcock.

There are places on earth that allay the nagging apprehensions intrinsic to a man-made world. This is one of them. If I am to be mindful of my frailties, and of forgiving them, too, then I must visit here often. I must submit to it. Then, I am at peace. A bird in the bag is just a bonus.

I long for morning walks in the glory of dying seasons.

We hold a great affection for the deep tradition of American storytelling. The ability to spin a yarn that can hold our attention and provide a gentle direction for life is something that has been with us for a long time. The celebrated “Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” by Mark Twain or Ernest Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories hold us with their gentle wit and carry us away for just a little while. In Outdoor Chronicles, Jerry Hamza takes up the gauntlet of the storyteller to take readers away for a little fun. There are already plenty of how-to fishing and outdoor books, and this is not one. Hamza’s stories will not make you a better caster or shooter, but they will make you want to spend more time fishing or hunting.

We hold a great affection for the deep tradition of American storytelling. The ability to spin a yarn that can hold our attention and provide a gentle direction for life is something that has been with us for a long time. The celebrated “Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” by Mark Twain or Ernest Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories hold us with their gentle wit and carry us away for just a little while. In Outdoor Chronicles, Jerry Hamza takes up the gauntlet of the storyteller to take readers away for a little fun. There are already plenty of how-to fishing and outdoor books, and this is not one. Hamza’s stories will not make you a better caster or shooter, but they will make you want to spend more time fishing or hunting.

This book is a collection of outdoor stories wrapped in the human condition. They were written with an eye toward honesty and cynicism. They will make you laugh out loud, and you will want to carry them with you wherever you go. If this book goes missing, it’s a sure thing that, when you do find it, it will be in the possession of a member of your household, regardless of their interest in casting a fly. The stories cover the gamut from a fishing trip to northern Canada to a little stream that was actually better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek along railroad tracks during a cold, dark, and dreary February and many more. Buy Now