Whether he was shooting grouse or skeet, painting bird dogs or promoting wildlife conservation, William Harnden Foster never wavered in his unrelenting pursuit of perfection.

Whether he was shooting grouse or skeet, painting bird dogs or promoting wildlife conservation, William Harnden Foster never wavered in his unrelenting pursuit of perfection.

I would like to have known William Harnden Foster — hunted with him, sat in his study talking about bird dogs and Parker guns, listened to his thoughts on hunting and shooting and conservation. Bill, to all his friends, left an indelible mark on our sporting life. We remember him mostly for his wonderful paintings and drawings, but his range and versatility as a sportsman can only be appreciated by researching his many interests and accomplishments. To me, his book New England Grouse Shooting will remain near and dear to all who venture forth into old apple orchards, alder runs or overgrown, abandoned farms in pursuit of grouse and woodcock.

Foster’s family hailed from Tewksbury, a small hamlet in the northeast corner of Massachusetts, though most of his favorite grouse haunts were at nearby Andover. His passion or “pa’tridge gunning” became the foundation for many of his endeavors, and his studious approach to the sport is a common theme in his book. If he missed a certain shot, he would return to the range to replay the event with clay targets. This dogged pursuit of perfection is likewise reflected in his art. Foster was unwilling to take on a project unless he knew everything he could about it. His illustrations, paintings, writings and shooting skills — all reflect the precision of a master technician.

Drawing and sketching always interested Foster, and with his father and uncles being railroad men, he grew up in an atmosphere steeped in train talk. Born on July 22, 1886, Foster began drawing pictures of trains while in grade school, often under the watchful eye of Uncle Virgil, an engineer for a local railroad and a dyed-in-the-wool grouse hunter.

From these raw artistic beginnings grew an intense desire to study art. In 1904, within months after graduating from high school, Foster enrolled at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts where for the next three years he studied under Frank Benson, Philip Hale and Edmund Tarbel. Then, beginning in 1908, he spent another three years at the Howard Pyle Art Colony in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

Pyle at the time was recognized as America’s greatest illustrator, and Bill Foster was one of his “carefully selected” students. The prestigious Brandywine School provided inspiration and instruction for not only Foster, but for a number of other painters and illustrators who would go on to earn international renown, including N. C. Wyeth, Frank Stick, Oliver Kemp, Frank Schoonover and Philip Goodwin.

Pyle at the time was recognized as America’s greatest illustrator, and Bill Foster was one of his “carefully selected” students. The prestigious Brandywine School provided inspiration and instruction for not only Foster, but for a number of other painters and illustrators who would go on to earn international renown, including N. C. Wyeth, Frank Stick, Oliver Kemp, Frank Schoonover and Philip Goodwin.

It was during Foster’s last year at Brandywine that Pyle encouraged the young artist to submit his train pictures to the editors of Scribners magazine in New York. Though somewhat dubious about the idea, Foster took Pyle’s advice and much to his surprise, he sold the entire portfolio for a price beyond his wildest dreams. Scribners then asked Foster to write something about the paintings, a job that he tackled with his typical enthusiasm. His text was so well written that the editors didn’t change a word. Scribners requested more of his work, including two illustrated stories documenting construction of the Panama Canal and another series devoted to “aeroplanes” of the day.

Foster’s paintings of locomotives were particularly unique because of the way he imparted a sense of motion. “Most artists back then created a feeling of speed simply by blurring the lines of their subject, like what you would see in a Wiley Coyote cartoon,” says Jon Foster, a grandson who lives in Newark, Delaware. “But grandfather’s technique was to place the observer right down on the tracks, real low so the engine looms over you. The result is that the massive engine seems to be hurtling toward you at an enormous rate of speed.”

Both because of his knowledge of trains and his skill in painting them, it was only natural that Foster be commissioned to paint the Century, New York Central’s famous locomotive. True to form, Foster took a special course at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in locomotive maintenance to learn everything he could about the Century. He rode in the locomotive to immerse himself in its atmosphere. With painstaking accuracy Foster approached the project, determined not to overlook any detail — down to even the smallest bolt! — that might make his work inaccurate.

Both because of his knowledge of trains and his skill in painting them, it was only natural that Foster be commissioned to paint the Century, New York Central’s famous locomotive. True to form, Foster took a special course at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in locomotive maintenance to learn everything he could about the Century. He rode in the locomotive to immerse himself in its atmosphere. With painstaking accuracy Foster approached the project, determined not to overlook any detail — down to even the smallest bolt! — that might make his work inaccurate.

The artist went on to create three more pictures for New York Central: The Pride of the New York Central Men, The Greatest Train in the World and As the Centuries Pass in the Night. His painting of the Century hung in New York’s Grand Central Station for many years, then became part of an exhibit at a railroad museum in Cape Cod. Unfortunately the museum no longer exists and the whereabouts of Foster’s painting is unknown.

In the years to come, Foster would do commercial art for Oldsmobile, DuPont, Missouri Pacific and Motorboat magazine, each time drawing from his own experiences, whether it be hunting, trains or boats.

During World War I, Foster was employed as a commercial draftsman in the maritime industry. He designed and built his own 24-foot Hampton powerboat, which he called The Whistler. He also constructed several other small watercraft, among them a duck boat built with the help of a friend, Leon Leonwood Bean. L. L. Bean and the artist hunted together from time to time and Foster’s paintings appeared on a number of the Maine company’s catalogs. His very first cover painting, entitled The Moose Hunter, is still part of L.L. Bean’s art collection.

In this circa 1930 photograph, Foster (left) chats with

noted Boston shooter Or. Hughe Williams and 75-year-old Baylor Van Meter, one of the rising stars in skeet shooting at the time.

But it was Foster’s love of bird dogs, grouse hunting and wingshooting that would ultimately have the greatest impact on the sporting community.

For years Foster was concerned that hunters were using their guns only during the hunting season and interest in shooting waned after that.

His personal surveys suggested the average hunter spent only four days of actual shooting a year and the rest of the time his shotgun sat idle in the gun case or cabinet. Improved shooting ability, he knew, was a good conservation measure, and constant practice at the range resulted in better judgment of distance and proper lead in the gamefields. Recalling his boyhood experiences, Foster was convinced that if a shooting game could be devised, it would polish the gunners’ skills and rekindle their interest in shooting year-round.

The seeds of the Sport we now call skeet were believed to have been sown on the grounds of Glen Rock Kennels in the village of Ballardvale, now part of Andover. There, Foster and a small group of avid bird-hunters, among them C. E. Davis, owner of the kennels and his son, Henry W. Davis, often gathered to shoot their favorite guns.

Foster and his friends devised a game in which they would arrange themselves at positions completely encircling the trap. Shooting “round the clock,” as it was called, was great fun and challenging because the gunners had to constantly adjust to the different angles and leads required to break the clay birds.

Between 1910 and 1915, shooting “round the clock” became a popular pastime in Andover, and a friendly competition developed between Foster and his friends. This rivalry set the stage for a more standardized competition in which each participant would take the same series of shots. But Foster always believed that moving shooters to different stations in a circle around the trap wasn’t really practical or safe. So, he decided to arrange the stations in a half-circle with a thrower at each corner. The first trap, or high house, would simulate a driven bird; the second, or low house, a flushed bird.

Between 1910 and 1915, shooting “round the clock” became a popular pastime in Andover, and a friendly competition developed between Foster and his friends. This rivalry set the stage for a more standardized competition in which each participant would take the same series of shots. But Foster always believed that moving shooters to different stations in a circle around the trap wasn’t really practical or safe. So, he decided to arrange the stations in a half-circle with a thrower at each corner. The first trap, or high house, would simulate a driven bird; the second, or low house, a flushed bird.

In 1920, National Sportsman Inc., publishers of Hunting and Fishing and National Sportsman, employed Foster as an assistant editor. It was in these periodicals that Foster introduced, supported, administrated and directed his new shooting sport. The two magazines even ran a contest asking readers to come up with a name for it. Mrs. Gertrude Hurlbutt claimed the $100 first prize when she suggested “Skeet,” from a Scandinavian interpretation of the word “shoot.”

In 1927, Remington Arms Co. Inc. established a shooting range at its Lordship, Connecticut site. Though basically a trap club, the Lordship facility enabled shooters to try their hand at skeet. The new pastime quickly grew in popularity and in 1935 the first National Skeet Championships were held in Solon, Ohio, with 167 shooters on 26 fields. Today, boasting 25,000 members, the National Skeet Shooting Association is an important and active organization, thanks to Bill Foster, its first president and first inductee into the Skeet Shooting Hall of Fame.

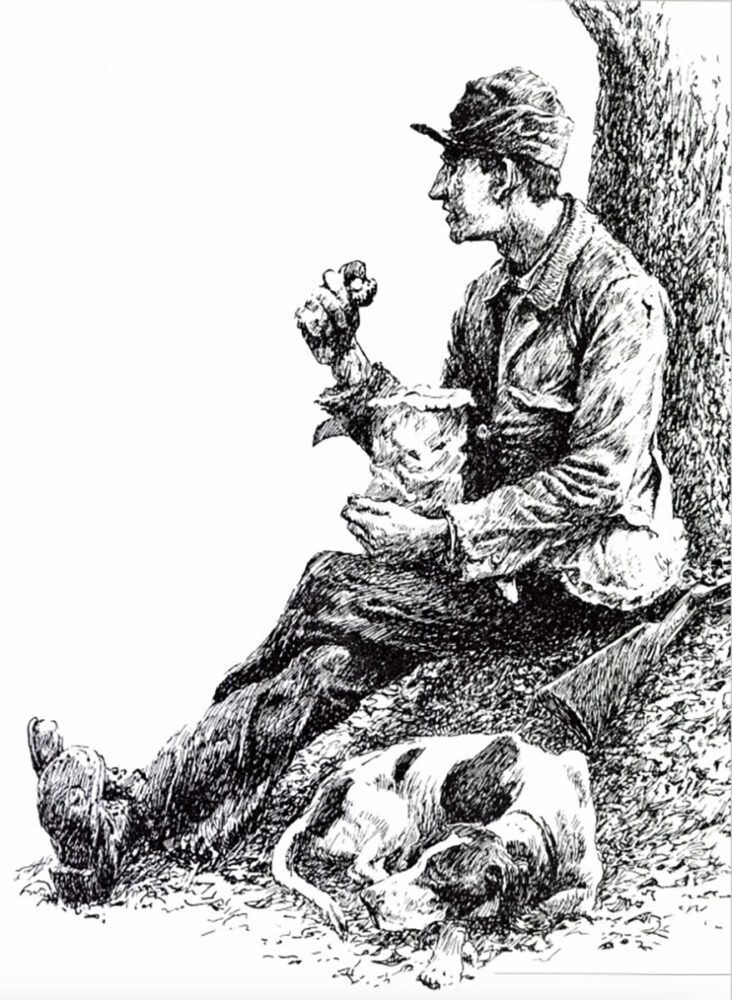

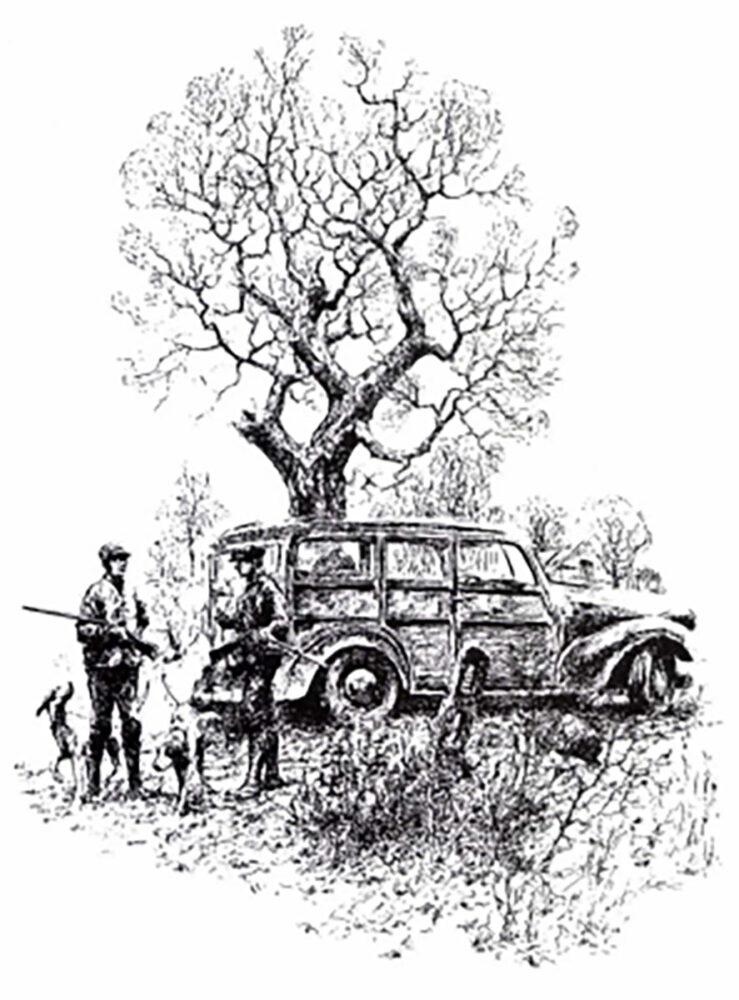

This delightful scene is among hundreds of Foster’s magazine illustrations, many of them light-hearted, folksy compositions a la Norman Rockwell.

Though Foster is now widely recognized as the father of skeet shooting, few realize that he was also a pioneering conservationist who made significant contributions in the development of fish and wildlife management. In 1932 he testified at the Senate hearing on waterfowl in Washington, D. C., advising that a biological survey be conducted at year’s end to determine statewide seasons. He urged lawmakers to not act hastily adopting a shell tax or an increase in license fees. These hearings ultimately led to establishment of the duck stamp bill.

It’s interesting to note that Nash Buckingham “weighed in” via at least one letter to Foster, dated January 26, 1932, from Memphis, Tennessee. It begins with “My dear Bill —” and goes on to state: “You are right when you say that more action must be given to sectional climes and conditions” and “You have done mighty well to keep in the middle of the road.” Buckingham concludes with “I’ll always be interested in ‘Conservation’ and not a damn bit afraid to do my own thinking and speak up.”

William Harnden Foster’s artistic ability, for whatever reason, has never received its true acclaim. His pictures of sporting events, trains and bird dogs were gems, characterized by exacting study and firsthand knowledge of each subject or situation. No wonder his bird dogs come to life on canvas when one understands he was the owner and handler of “Ding’s Palmetto Kent,” “Dapple Joe’s Bend,” and “Along Came Ruth.” His series of bird dog paintings for a DuPont calendar are prizes for any lover of gundogs.

Altogether, Foster did more than 250 magazine covers (many with just the letter “F” as a signature), as well as numerous calendar, catalog and poster illustrations for arms and ammunition manufacturers. His flawless execution, arresting sense of composition and diverse range of subjects are appreciated by those lucky enough to have seen his original paintings — and even more by those who own one. Some of his images have a folksy Norman Rockwell look to them; almost all impart a strong sense of “being there.”

We know that Foster spent considerable time around Merrymeeting Bay in Maine, one of the great duck-hunting tidewaters in the Northeast and home to the finest black duck shooting in the country. Little is known and nothing has been written about his decoy carving accomplishments, but a few examples have survived. Certainly, Foster was never recognized for his decoys, but after careful examination of the few still in existence, we know that his artistic ability comes through loud and clear. Some experts believe Foster decoys rank right up there with some of his famous contemporaries.

Skeet-shooting writer Gertrude L. Travis posed for this 1905 painting for Motorboat magazine. Foster designed his own powerboat and collaborated with another good friend, L.L. Bean, to build a duck boat.

Foster’s most memorable work, at least to bird hunters, is his only book: New England Grouse Shooting. Foster apparently drew from many observations and experiences in his favorite grouse coverts to write the book. I have read a number of his submissions, and clearly, he knew his material intimately. Foster made a science out of discovering how and why grouse are missed. With uncanny ability he recreated different wingshooting situations in his drawings and piqued reader interest though his writing. His easy style, smooth transitions and appealing characterizations of local gunners make New England Grouse Shooting a treat to read on that cold, snowy evening as you dream of the next season,

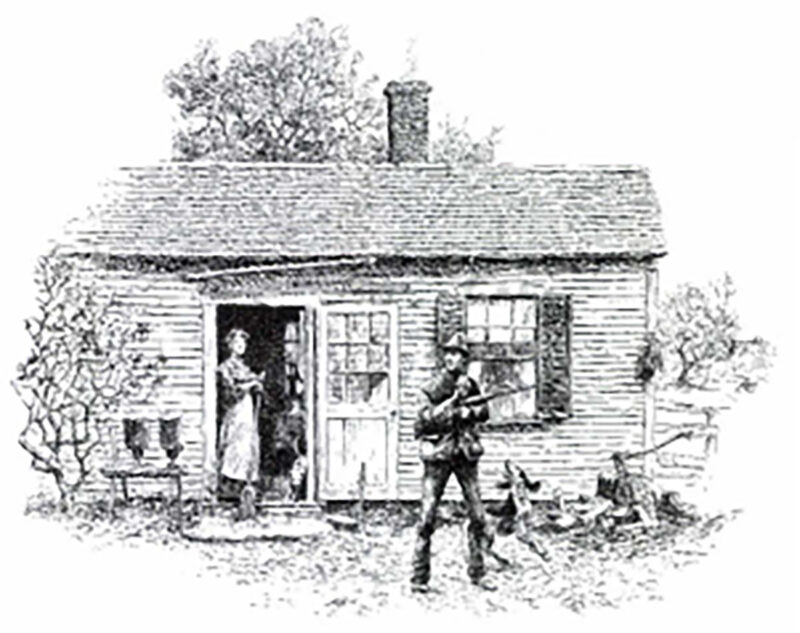

Foster’s black-and-white sketches in the book are particularly wonderful. Superbly drawn, they range from simple pen-and-ink vignettes of ruffed grouse, bird dogs, guns, boots and other gems to elaborately detailed hunting scenes, each recreated from his own observations in the field. In the history of sporting literature, few books can match Grouse Shooting’s eclectic array of black-and-white sketches.

Published posthumously in 1942 by Charles Scribners Sons, New England Grouse Shooting remains a classic. A second edition, approved by his son, Bill Foster Jr. in 1970, was also published by Scribners and a special “memorial” edition was produced by Willow Creek Press in 1983.

The book touches the soul of the grouse hunter. In the Introduction for the 1970 version, the great outdoor writer Edmund Ware Smith wrote: “l owe much to Bill. He had a great ear for that which was false and his gentle scorn for purple passages in writing has served me well. It was he who taught me much of what I know about grouse hunting and I shall always remember his silent and effortless way of getting through the woods: his affection, at times amounting to reverence for the cover and scenery around Wadleighs Falls and Lee, New Hampshire and Martins Pond and Dawn Shots near Andover, his boyhood haunts.”

For anyone who has ever owned a double gun, the first chapter, titled “The Little Gun,” is especially appealing. It covers the early beginnings of a 16-gauge Parker that had been in the Foster family for five generations (a complete story of its history and details from Parker Company records appeared in Double Gun Journal, volume 12, issue 4 in 2001). The chapter concludes with the kind of writing that every hunter, young and old alike, will treasure:

“With hopeless attempt at nonchalance, into the kitchen I walked, set The Little Gun in its corner, and with a feigned air of indifference tossed my pa’tridge onto the heap, noting, at the same time, where it landed. My grandfather said nary a word. He just got up slow-like, fished out his worn purse of the many compartments and handed me 65 cents. Then he sat down again. I wish I might see him do it over again — now. I’d look for the twinkle in his calm eyes that I know was there that big night when I was twelve.

“With hopeless attempt at nonchalance, into the kitchen I walked, set The Little Gun in its corner, and with a feigned air of indifference tossed my pa’tridge onto the heap, noting, at the same time, where it landed. My grandfather said nary a word. He just got up slow-like, fished out his worn purse of the many compartments and handed me 65 cents. Then he sat down again. I wish I might see him do it over again — now. I’d look for the twinkle in his calm eyes that I know was there that big night when I was twelve.

“The Little Gun had begun to uphold its reputation in the trembling hands of the third generation.”

To truly appreciate Foster’s contribution to the American sporting life, you need to read every word of New England Grouse Shooting, in addition to his articles in Hunting and Fishing and National Sportsman. Published in the ’20s and ’30s, the magazines can be found in used bookstores or occasionally at flea markets. Not only are the advertisements and stories interesting, you might be lucky enough to find illustrations by Foster himself.

William Harnden Foster died suddenly from a heart attack on October 30, 1941, while judging the New England Bird Dog Championships in Scotland, Connecticut. He was only 55 at the time. Foster was remembered by family and close friends as cordial and soft spoken, with a quiet sense of humor and boundless energy. Bill Jr., in his 1970 Foreword for the Willow Creek Press edition, wrote: “Whether he was painting a picture, writing a book or carving a decoy, he tried to show and describe things as they were — in detail, but without frills or embellishments. Even now, 40 years later, they still ring true.” William Harnden Foster’s mark on the American shooting scene — his colorful illustrations, beautiful oil paintings of sportsmen and bird dogs, and of course his role as the father of skeet — altogether make him a man for all seasons. Hopefully, more Americans will gain an appreciation for this wonderful sportsman and his enduring legacy.

Jacob F. Rivers’s Cultural Values in the Southern Sporting Narrative examines classic southern fiction—along with lesser-known literary works—with an eye to the ways that southern writers such as William Elliott, William Gilmore Simms, and William Faulkner depict hunting and outdoorsmanship. Blending literary history with sociology and cultural criticism, Rivers explores the recurring themes of honor, fair play, and noblesse oblige and illustrates how the sporting genre has reflected the moral consciousness of the American South. Buy Now

Jacob F. Rivers’s Cultural Values in the Southern Sporting Narrative examines classic southern fiction—along with lesser-known literary works—with an eye to the ways that southern writers such as William Elliott, William Gilmore Simms, and William Faulkner depict hunting and outdoorsmanship. Blending literary history with sociology and cultural criticism, Rivers explores the recurring themes of honor, fair play, and noblesse oblige and illustrates how the sporting genre has reflected the moral consciousness of the American South. Buy Now