The hunt and the wilderness were more than just an escape for William Faulkner. They also taught him patience and self, discipline and were the inspiration for some of his greatest literary works.

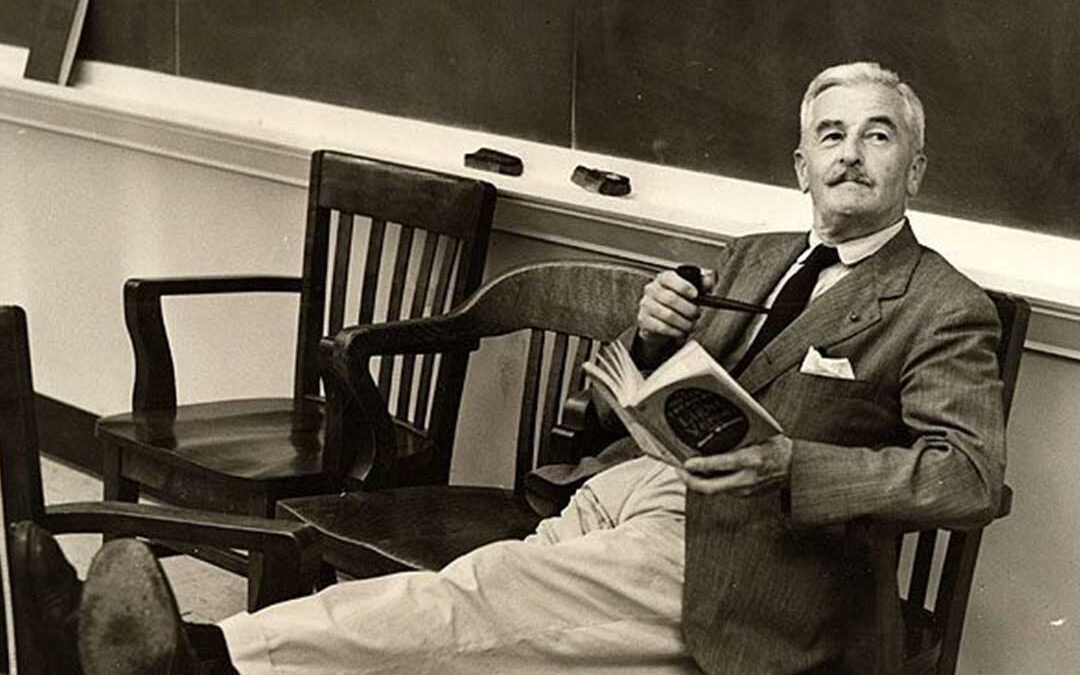

Early on the morning of November 10, 1950, William Faulkner received a phone call from a Swedish newspaperman informing him that he had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. The award is the greatest honor a living writer can receive, and for Faulkner, whose novels and short stories had been ignored for so many years by the literary establishment, it was a long overdue acknowledgement of America’s greatest 20th century writer.

Early on the morning of November 10, 1950, William Faulkner received a phone call from a Swedish newspaperman informing him that he had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. The award is the greatest honor a living writer can receive, and for Faulkner, whose novels and short stories had been ignored for so many years by the literary establishment, it was a long overdue acknowledgement of America’s greatest 20th century writer.

In the following days Faulkner was besieged by newspapermen and well-wishers, who no doubt expected him to spend the succeeding weeks basking in the spotlight of his sudden international fame or preparing his Nobel Prize acceptance speech for the award ceremonies he would attend in Stockholm, Sweden on December 10. Faulkner, however, had another trip in mind.

On November 16 he mailed a hurriedly typed letter filled with typographical errors to Sweden, politely explaining he would not attend the Nobel Prize ceremonies. Duty out of the way, Faulkner turned his full attention to a more important matter: preparing for his annual week in deer camp. He gathered his guns and supplies, and the next day disappeared into the wilderness and isolation of the Mississippi Delta, leaving behind a legion of frustrated reporters who wandered around Oxford, Mississippi, like jilted suitors.

After it became known that Faulkner had told the Swedish officials he would not be coming to Stockholm to accept his prize, these reporters were joined by a group of anxious State Department officials who wanted desperately to convince the writer that it was his duty as an American citizen to prevent an international incident. But there was no way to contact Faulkner, for he was miles from the nearest road or telephone. He did not return until November 27, ten days after he had left. Protocol was to prevail, however, thanks to friends and relatives who finally persuaded Faulkner to attend the ceremonies.

This anecdote tells us much about Faulkner, a private man who disdained the attention of intellectuals and literary critics, preferring instead the company of simple, unassuming men who, as he once put it, were not “even very literate, let alone literary.” He was also a man who, as an accomplished hunter and outdoorsman, was much more comfortable in the silence and isolation of the wilderness than in the sound and fury of a city.

The “big woods,” as he called them, offered Faulkner an escape from the pressures of his art, a turbid personal life and, at least late in his life, fame. But the hunt and the wilderness were more than just an escape for Faulkner; they were also an inspiration for some of his greatest literary works.

“He taught the boy the woods, to hunt, when to shoot and not to shoot, when to kill and when not to kill, and better, what to do with it afterward.” —Go Down, Moses, 1942

William Faulkner was probably destined to be a hunter and outdoorsman, for patience, self-discipline and an ability to work in solitude — the traits of both a writer and an outdoorsman, marked his character and temperament. These traits were developed amidst a family and society that made his interest in hunting and outdoors almost inevitable.

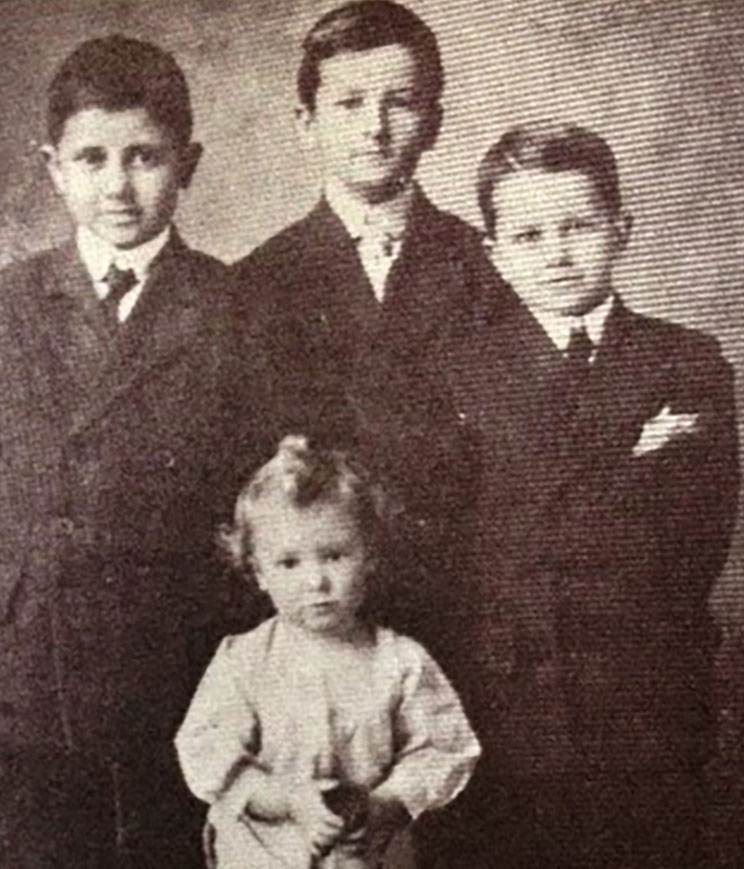

Faulkner was born in New Albany, Mississippi, on September 25, 1897, and moved with his family to Oxford in 1902. At that time northern Mississippi was sparsely populated, with many large pockets of forest, an area in which it was only natural that a boy would spend much of his time hunting rabbits and small game in the woods. This was especially true if the boy’s father was an avid hunter, as Faulkner’s father was.

Faulkner was born in New Albany, Mississippi, on September 25, 1897, and moved with his family to Oxford in 1902. At that time northern Mississippi was sparsely populated, with many large pockets of forest, an area in which it was only natural that a boy would spend much of his time hunting rabbits and small game in the woods. This was especially true if the boy’s father was an avid hunter, as Faulkner’s father was.

Murry Falkner (William Faulkner preferred to spell his last name with a “u”) had many failings as a father. He had a tendency to drink too much (a trait he shared with his oldest child, William) and was often insensitive, morose and taciturn around his four sons, except when he took the boys to a nearby hunting lodge, of which he was a member or on long walks in the woods on autumn Sundays. Here he was in his element, for Murry Falkner was a man who derived much pleasure from walking and hunting in the woods.

As Faulkner’s younger brother John would recall years later, “It was here in the woods that he came closest to his children.”

During such times the elder Falkner would often tell his sons about past hunts, like the time he had shot a panther in Tippah County, or another time when he had shot an eagle, the last ever seen in the region, that had been killing a farmer’s lambs. There were hundreds of other stories that left an indelible imprint on the young William’s imagination.

Murry Falkner did more than just tell stories; he also taught his sons all the skills necessary to be good hunters and outdoorsman. At age eight, each boy was given an air rifle and was taught to use it as if it were a real gun. At ten they graduated to rifles and at 12 were given shotguns. The elder Falkner also bought two beagles with which the boys could hunt rabbits.

By the time he was a teenager, Faulkner was an accomplished hunter and was already displaying some of the characteristics that would mark him as a hunter for the rest of his life. Even as an adolescent he had a sincere respect for the game he pursued. He ate what he killed and never let an animal he shot suffer needlessly; nor would he ever leave a creature he had crippled, refusing to hunt further until it was found.

Once, unable to find an injured bird before dark, he returned the next morning to continue the search. Young Faulkner’s forays into the local woods with his gun taught him valuable lessons about courage, love, pity and responsibility, words the writer would later use to describe what the big woods had taught young Isaac McCaslin in “The Bear.”

In the fall of 1911, however, Faulkner received a particularly brutal lesson, one that almost made him give up hunting forever. While hunting rabbits after school one day, Faulkner accidently shot and killed one of the beagles his father had given him and his brothers. As soon as he realized what had happened, he dropped his gun and, leaving it where it lay, carried the dead dog back home. He lay the dog on the porch and went to his room, locked the door and then allowed himself to cry. The event was so traumatic that it would be years before he would regain his interest in hunting; he would never again use the shotgun with which he had killed the dog.

No one seems to be exactly sure when Faulkner began to hunt again, though Joseph Blotner, the writer’s biographer, says it was probably during the fall of 1915. No longer was Faulkner hunting the squirrels and rabbits of his boyhood; he had been invited to join a group of fellow Oxfordians to hunt deer and bear at General James Stone’s deer camp on the edge of the rich, untamed Mississippi Delta about 30 miles from Oxford. Here the young man quickly regained his enthusiasm for hunting.

Because he was a novice, he was given the least desirable and the most remote deer stand, but he accepted this as fair and stayed at his stand until the other hunters came for him late in the evening. His patience and fortitude paid off; not only did he gain the respect of the other hunters, but he also killed his first buck. The still-warm blood of the freshly killed deer was smeared on Faulkner’s face as he participated in the timeless ritual of being “blooded” after his first kill. It was a moment that he apparently never forgot, for a quarter of a century later he would use a similar moment to mark a boy’s transition towards manhood in his short story “The Old People”:

Because he was a novice, he was given the least desirable and the most remote deer stand, but he accepted this as fair and stayed at his stand until the other hunters came for him late in the evening. His patience and fortitude paid off; not only did he gain the respect of the other hunters, but he also killed his first buck. The still-warm blood of the freshly killed deer was smeared on Faulkner’s face as he participated in the timeless ritual of being “blooded” after his first kill. It was a moment that he apparently never forgot, for a quarter of a century later he would use a similar moment to mark a boy’s transition towards manhood in his short story “The Old People”:

“So the instant came. He pulled the trigger and Sam Fathers marked his face with the hot blood which he had spilled and he ceased to be a child and became a hunter and a man.”

There was more to deer camp than just the actual hunt, however; there were the many hours spent around the campfire drinking and telling stories of past hunts. Faulkner listened quietly but intently to the older hunters.

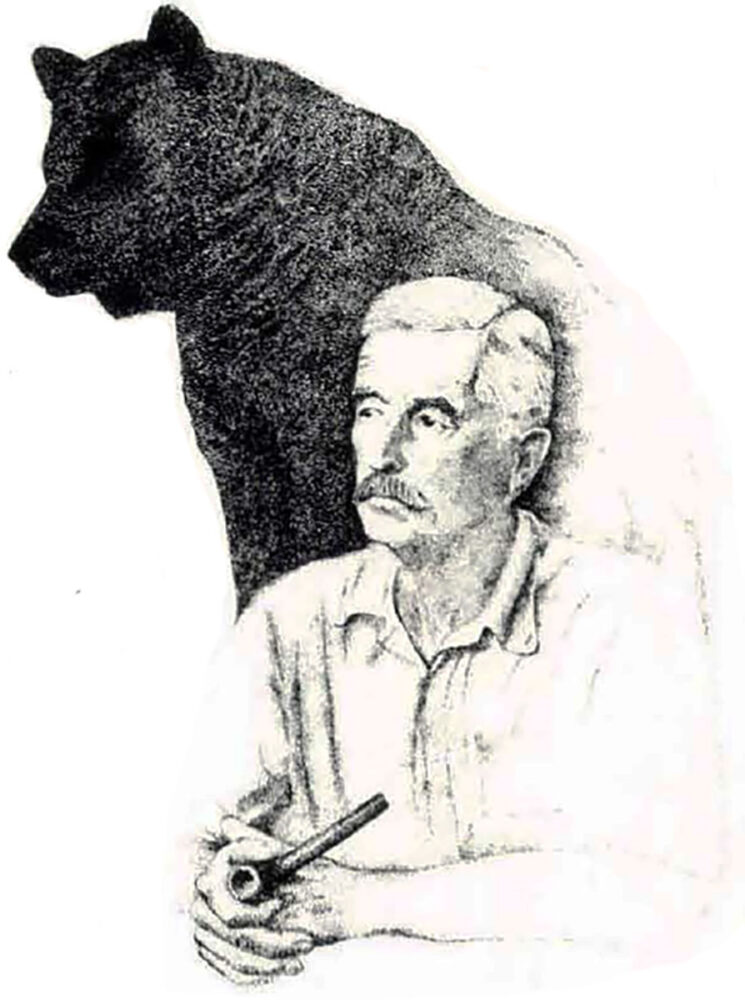

One story he heard during these early deer hunts particularly captured his imagination. It was about a legendary bear called Old Reel Foot (so named because of the two missing front toes on its front left paw) that had evaded some of the older hunters for about two decades. Once a hunter measured the great bear’s track and found them to be eight inches wide.

There had been many epic battles between Old Reel Foot and the dogs and men who pursued him, but the great bear always won, once killing 25 of 27 dogs that had pursued it into the cane and vine thicket that was its home.

Late in life Faulkner would remember Old Reel Foot in an interview and credit the stories he had heard around the campfire as the inspiration for one of his finest pieces of writing, “The Bear.”

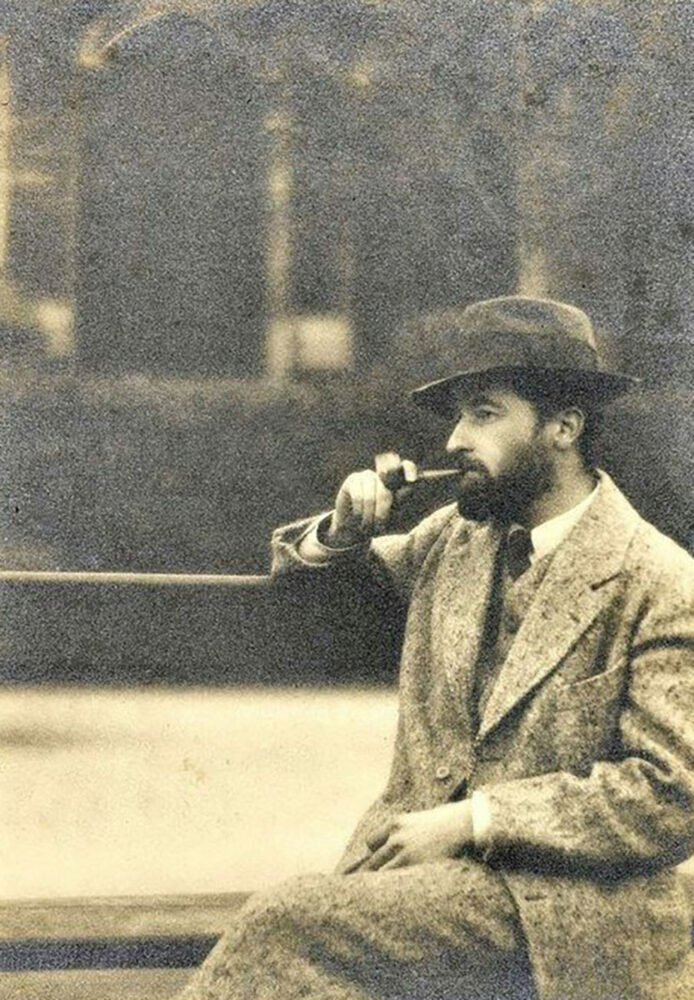

All of this would occur much later, however, because at this time young Faulkner was not seeking inspiration from the people, places and events around him. Soon, like many young artists, he would leave the provincial world he had grown up in and travel to New Orleans, New York and Paris.

From 1918 to 1927, Faulkner would spend much of his time away from Mississippi, though he would often go to deer camp if he happened to be in Oxford in the late fall. His writing reflected this newfound worldliness, and his first two novels (Soldiers Pay, 1926; Mosquitoes, 1927) suffered from his attempt to write about a world he didn’t really know or understand.

From 1918 to 1927, Faulkner would spend much of his time away from Mississippi, though he would often go to deer camp if he happened to be in Oxford in the late fall. His writing reflected this newfound worldliness, and his first two novels (Soldiers Pay, 1926; Mosquitoes, 1927) suffered from his attempt to write about a world he didn’t really know or understand.

In 1927, William Faulkner finally returned to Oxford to live, having taken the advice of fellow author Sherwood Anderson, whom Faulkner had met in New Orleans in 1925.

“You’re a country boy,” the older, more experienced writer had told him. “All you know is that little patch up there in Mississippi where you started from.” But Anderson also assured the younger writer that knowledge of “that little patch” was more than enough for any writer to make great literature, providing he had the talent.

So Faulkner came home not only to live but to write about his “little postage stamp of native soil,” and though he would occasionally leave Oxford in the following decades, it was almost always out of economic necessity.

His third novel, Sartoris, was set in northern Mississippi, the world Faulkner had grown up in. In his fictional representation of that world, Faulkner finds his heroes, his “tall men,” living not in towns and cities but in the isolation of wilderness. They are hunters and farmers who are brave, loyal, compassionate, independent men who, unlike so many of the characters in the book, are still close enough to nature to respect it and to be humble in its presence:

“Listen. The talking ceased.And again across the night the dogs’ voices rang among the hills, long, ringing cries fading, falling with a quartering suspense, like touched bells or strings repeated and sustained; by bell-like echoes repeated and dying among the dark hills beneath the stars, lingering yet in the ear, crystal-clear, mournful and valiant and a little sad.” – Sartoris, 1927

They are in many ways the kind of men the writer hunted with on his autumn treks into the delta, but one incident in Sartoris was, if not inspired by, at least worthy of a late-night telling around a deer campfire. The story concerned Jackson MacCallum’s hybrid hunting dogs, half hound and half fox, which displayed the worst traits of both species: “Can’t smell, can’t bark and damn if I believe they kin see,” one character comments.

They are in many ways the kind of men the writer hunted with on his autumn treks into the delta, but one incident in Sartoris was, if not inspired by, at least worthy of a late-night telling around a deer campfire. The story concerned Jackson MacCallum’s hybrid hunting dogs, half hound and half fox, which displayed the worst traits of both species: “Can’t smell, can’t bark and damn if I believe they kin see,” one character comments.

Faulkner finished Sartoris in September of 1927, and that November he probably once again participated in General Stone’s annual deer camp, despite some hesitancy on the part of some of the other hunters who weren’t sure a “book-writer” belonged in their camp.

As his brother John recalled: “Because he was a writer, the town had already begun to look at him as a little queer, and at first the other hunters didn’t know whether they’d get along with him or not.”

But Faulkner “asked no favors, just to be allowed to hunt with them and be one of them.” Not only did he continue to be accepted by these men, but as the years went by he played a larger and larger role in organizing the hunt.

In October 1929, William Faulkner married Estelle Olhman Franklin, who had been formerly married and had two children, and a few weeks later The Sound and the Fury, a book regarded by some critics as his greatest work, was published. However, during the next few years, Faulkner found it increasingly difficult to support his family, and in 1932, like other writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Nathaniel West, he went to Hollywood to make money as a screenwriter. He would spend more than four years there, but it was spread out over a 23-year span.

In October 1929, William Faulkner married Estelle Olhman Franklin, who had been formerly married and had two children, and a few weeks later The Sound and the Fury, a book regarded by some critics as his greatest work, was published. However, during the next few years, Faulkner found it increasingly difficult to support his family, and in 1932, like other writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Nathaniel West, he went to Hollywood to make money as a screenwriter. He would spend more than four years there, but it was spread out over a 23-year span.

Faulkner had gone to Hollywood to work, but he did occasionally have opportunities to hunt in southern California. In fact, two of the memorable anecdotes from Faulkner’s stay in Hollywood involved hunting.

The first occurred in the 1930s, when director Howard Hawks took Faulkner and Clark Gable, at that time one of the most famous men in America, dove hunting. The two had never met, and when the conversation turned to literature, Gable asked Faulkner whom he thought were the best writers of the present generation. Faulkner replied with a list of names that concluded with his own.

“Do you write, Mr. Faulkner?” Gable asked, genuinely surprised.

“Yes,” replied Faulkner, who not to be outdone, added, “What do you do, Mr. Gable?”

Another amusing incident occurred after Faulkner returned to the Beverly Hills Hotel from a wild boar hunt. He entered the hotel, unshaven, wearing his hunting clothes. As Faulkner walked across the hotel lobby to the main desk, the clerk gave a startled cry and dropped to the floor; a salesman ran out the door and two women fainted. It seems while Faulkner had been hunting, a robbery had taken place at the hotel and he had been mistaken for the returning gunman.

These hunts were a welcome distraction for the writer, who was often unhappy and homesick in Hollywood. Fortunately, he was able to go back to Oxford and work on his own fiction.

Once home there was time to hunt, and during the 1930s and 1940s Faulkner spent much of his free time hunting small game in the woods surrounding Oxford. Aside from the pleasure he derived from the pursuit, killing and eating of the game, hunting also allowed him to refresh himself after a long stint at the typewriter.

Sometimes it even allowed him to avoid unwanted social engagements, as when Russia’s national ballet troupe appeared in Oxford and Faulkner was invited to meet one of the star ballerinas. “Please tell the lady I have a previous invitation to hunt a coon,” he told the bearer of the invitation.

Faulkner certainly enjoyed these brief respites in the woods, but it was the late-November deer hunts that inspired so much of his writing during his middle years.

Faulkner certainly enjoyed these brief respites in the woods, but it was the late-November deer hunts that inspired so much of his writing during his middle years.

Faulkner feared the destruction of the wilderness in a way that transcended his personal concerns.

During the 1930s and 1940s William Faulkner’s role at the deer camp was changing. Now one of the veterans, he delegated an increasing amount of responsibility. Faulkner took these responsibilities seriously and was always willing, as another veteran noted, “to do his part of the hardest, dirtiest work in camp.” Another hunter put it more colorfully: “He’d take the front end of the log the same as I would, or anyone else.”

In 1935 Faulkner typed a charter for the Okatoba Hunting and Fishing Club, which gave the writer and his deer-camp companions exclusive hunting and fishing rights on land leased from General Stone, who had headed the first deer hunt the writer had been on nearly 20 years earlier. Such an organization had not been needed then, but as Faulkner was quite aware, the big woods and the wildlife that inhabited it when he was a teenager were now rapidly disappearing.

Faulkner expressed these fears to the state game commission in a letter in which he asked for a deputy game warden to be appointed for the newly chartered club land: “It is our intention to protect the game which is fast being exterminated in that section, and we want the help of your department to help us accomplish this aim.”

Nevertheless, by 1940 the hunters were no longer able to hunt on General Stone’s land, which had been denuded by timber companies. Instead, they were forced to establish their deer camp 150 miles southwest of Oxford on the Big Sunflower river.

Faulkner feared the destruction of the wilderness in a way that transcended his personal concerns, for he believed that many of mankind’s most admirable traits — humility, courage, responsibility, compassion, independence — were best learned in the woods and it was perhaps inevitable that these concerns would be the major theme of a short story he began working on in 1935.

The story was eventually called “The Bear,” and in the next seven years Faulkner would expand it until it reached novella length; he would then add six shorter stories, including two more set in the big woods, “The Old People” and “Delta Autumn.” The collection, titled Go Down, Moses, was published in 1942.

Go Down, Moses is a book with many characters and many themes, but the heart of the book centers on the growth and development of young Isaac McCaslin. We first meet Ike as a boy in “The Old People,” but in “The Bear” we see him attain manhood by participating in the yearly hunt for a giant bear named Old Ben.

As Faulkner would note in an interview, the boy “learned about man. About courage, about pity, about responsibility from that bear.” However, although Go Down, Moses celebrated the writer’s belief that the wilderness could teach these essential lessons, the book also reflects his grave fear that man would soon destroy the wilderness.

As Faulkner would note in an interview, the boy “learned about man. About courage, about pity, about responsibility from that bear.” However, although Go Down, Moses celebrated the writer’s belief that the wilderness could teach these essential lessons, the book also reflects his grave fear that man would soon destroy the wilderness.

In “Delta Autumn,” the story that follows “The Bear,” Isaac McCaslin, now an old man, lives in a “land across which there came now no scream of the panther but instead the loud hooting of locomotives” and where “paths made by deer and bear became roads and highways”:

“At first they have come in wagons: the guns, the bedding, the dogs, the food, the whiskey, the keen heart-lifting anticipation of hunting; the young men who could drive all night and all the following day in the cold rain and pitch a camp in the rain and sleep in the wet blankets and rise at daylight the next morning and hunt. There had been bear then. . . But that time was gone now. Now they went in cars, driving faster and faster each year because the roads were better and they had farther and farther to drive, the territory in which game still existed drawing yearly inward. . ..” —“Delta Autumn”

It was during this portion of his life (the 1930s and 1940s) that Faulkner spent the most time in deer camp and acquired many of the anecdotes about his time in the wilderness. According to those who hunted with him, men such as Red Brite, Ike Roberts and John Cullen, Faulkner would sit with the other men around the campfire at night to drink and tell stories. There, though reticent by nature, he would sometimes join in the storytelling.

The other hunters enjoyed listening to him, although, as John Cullen observed, Faulkner’s tales were often more complex and harder to follow than those told by other hunters. Cullen concluded that while Faulkner told a story “fairly well,” some of the other hunters were better storytellers. Usually Faulkner would simply sit quietly and listen. Sometimes he would unobtrusively write down a few notes, evidently for future fictional development.

These men had fewer reservations about Faulkner as an outdoorsman and hunter than a writer, for he was an expert with a compass and an excellent shot. He was also known as a man who was reluctant to shoot a doe, even when it was legal (as it almost always was) to do so. According to John Cullen, he shot only two does in his many years at deer camp and killed these only because they needed the meat at camp.

Although the men who hunted with Faulkner had known he was an author, few, if any, realized how great a writer he really was, especially since the world had largely ignored his literary genius in the 1920s, 30s and early 40s. However, Faulkner began to achieve worldwide acclaim in the late ’40s, and when the deer camp convened in the fall of 1950, they suddenly had a Nobel Prize winner in their camp.

At first, Faulkner was the only one in camp who knew he had won the prize since he had never cared to discuss his writing in camp and saw no reason to begin. But on the second day a hunter who had brought a newspaper to camp broke the news. That night the hunters celebrated with a feast of “coons and collards,” one of Faulkner’s favorite dishes.

Nevertheless, there was a slight uneasiness in the camp, for it was hallmark of Southern letters.

Uncle Ike Roberts, the elder statesman of the group, asked a question many of the other men must have been silently thinking: “Bill, now that you got all that money, I hear your head’s so big you’re not goin’ huntin’ with me anymore.”

Uncle Ike Roberts, the elder statesman of the group, asked a question many of the other men must have been silently thinking: “Bill, now that you got all that money, I hear your head’s so big you’re not goin’ huntin’ with me anymore.”

Faulkner’s reply: “Hell, that’s just money. They haven’t got any deer meat over there,” seemed to satisfy Uncle Ike temporarily; but later that evening he asked another question: “Bill, what would you do if that Swede ambassador came down here and handed you that money right now?”

Faulkner, who was washing dishes, stopped just long enough to reply: “I’d tell him just to put it on the table over there and grab a dryin’ rag and help out.” This remark not only amused the other hunters but assured them William Faulkner was unchanged by the Nobel Prize.

There was one more amusing incident connected with the Nobel Prize. After the hunters returned from deer camp, one of Faulkner’s companions wrote the King of Sweden (who had given Faulkner his award in Stockholm) and invited him to next year’s deer camp to hunt and share “a coon and collard dinner, for if you are a friend of William Faulkner’s, you are a friend of ours.” The king politely declined the invitation.

William Faulkner went to several more deer camps in the 1950s and continued to do a lot of bird hunting around Oxford, but as he got older the kill became increasingly less important to him.

In 1946, Faulkner wrote a letter to a friend in which he mentioned a magnificent stag he had missed: “He was a beautiful sight. I’m glad now he got away from me though I would have liked his head.”

In 1954, he wrote another letter explaining that though he would be going to deer camp soon, he had no intention of shooting a deer, a sentiment he repeats in “Race at Morning,” a short story he wrote in the late summer of 1954 and which is included in Faulkner’s 1955 collection of hunting stories entitled Big Woods. In the story Mr. Ernest, a veteran hunter, refuses to shoot a wily buck he has pursued for years, pretending instead that he has forgotten to load his gun. For Faulkner, as for Mr. Ernest, the pleasure of the hunt now was in the pursuit, not the kill:

“Which would you rather have? His bloody head and hide on the kitchen floor yonder and half his meat in a pickup truck on the way to Yoknapatawpha County, or him with his head and hide and meat still together over yonder in that brake, waiting for next November for us to run him again?” – “Race at Morning,” Big Woods

With such an attitude toward hunting, it is not surprising that in the last years of his life Faulkner found increasing pleasure in the ceremonious sport of fox hunting, in which the quarry is pursued but rarely killed.

William Faulkner died on July 6, 1962. In the last half-decade of his life he did not return to the wild bottomlands of the Big Sunflower River to deer hunt, although he did maintain the lease on the land, evidently hoping to enter the bog woods at least one more time:

“. . . the Big Woods, shoved, pushed further and further down into the notch where the hills and the Big River met, where they would make their last stand. It would be a good one too, impregnable; by that time, they would be too dense, too strong with life and memory, of all which had ever run in them, ever to die―the strong irritable loud-reeking bear, the gallant high-headed stags looking longer than comets and pale as smoke, the music-ed and untiring dogs and the splattered horses and the men who rode them; himself too. Oh yes, he would think; me too. I’ve been too busy all my life trying to waste any living, to have any time left to die.” —“A Bear Hunt,” Big Woods

The world has lost William Faulkner but not his life’s work. We who read him today and profess to be outdoorsmen can still learn much from him, for Faulkner understood the wilderness and the hunt as only a few men can. It is our good fortune that he chose to share that knowledge with us.

The world has lost William Faulkner but not his life’s work. We who read him today and profess to be outdoorsmen can still learn much from him, for Faulkner understood the wilderness and the hunt as only a few men can. It is our good fortune that he chose to share that knowledge with us.

“It is his [the writer’s] privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past.” —Nobel Prize Address, December 10, 1950.

Jacob F. Rivers’s Cultural Values in the Southern Sporting Narrative examines classic southern fiction—along with lesser-known literary works—with an eye to the ways that southern writers such as William Elliott, William Gilmore Simms, and William Faulkner depict hunting and outdoorsmanship. Blending literary history with sociology and cultural criticism, Rivers explores the recurring themes of honor, fair play, and noblesse oblige and illustrates how the sporting genre has reflected the moral consciousness of the American South. Buy Now

Jacob F. Rivers’s Cultural Values in the Southern Sporting Narrative examines classic southern fiction—along with lesser-known literary works—with an eye to the ways that southern writers such as William Elliott, William Gilmore Simms, and William Faulkner depict hunting and outdoorsmanship. Blending literary history with sociology and cultural criticism, Rivers explores the recurring themes of honor, fair play, and noblesse oblige and illustrates how the sporting genre has reflected the moral consciousness of the American South. Buy Now