When it comes to portraying animals in motion, many wildlife art experts agree that Schatz has few peers — if any.

He is among western Europe’s most renowned wildlife artists. His paintings, some of which sell for as much as $40,000, have been displayed in several prestigious fine art museums, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Six years ago, the West German government awarded him a Kulturpreis — the highest honor an artist in that republic can receive. Yet for all the recognition, Manfred Schatz remains an enigma — private man who shuns publicity and who rarely ventures far from his studio, except to observe and hunt animals in the seclusion of Scandinavian forests.

“I prefer to let my paintings speak for themselves,” says the reclusive, 59-year-old West German. And indeed they do. For when it comes to portraying animals in motion, many wildlife art experts agree that Schatz has few peers — if any.

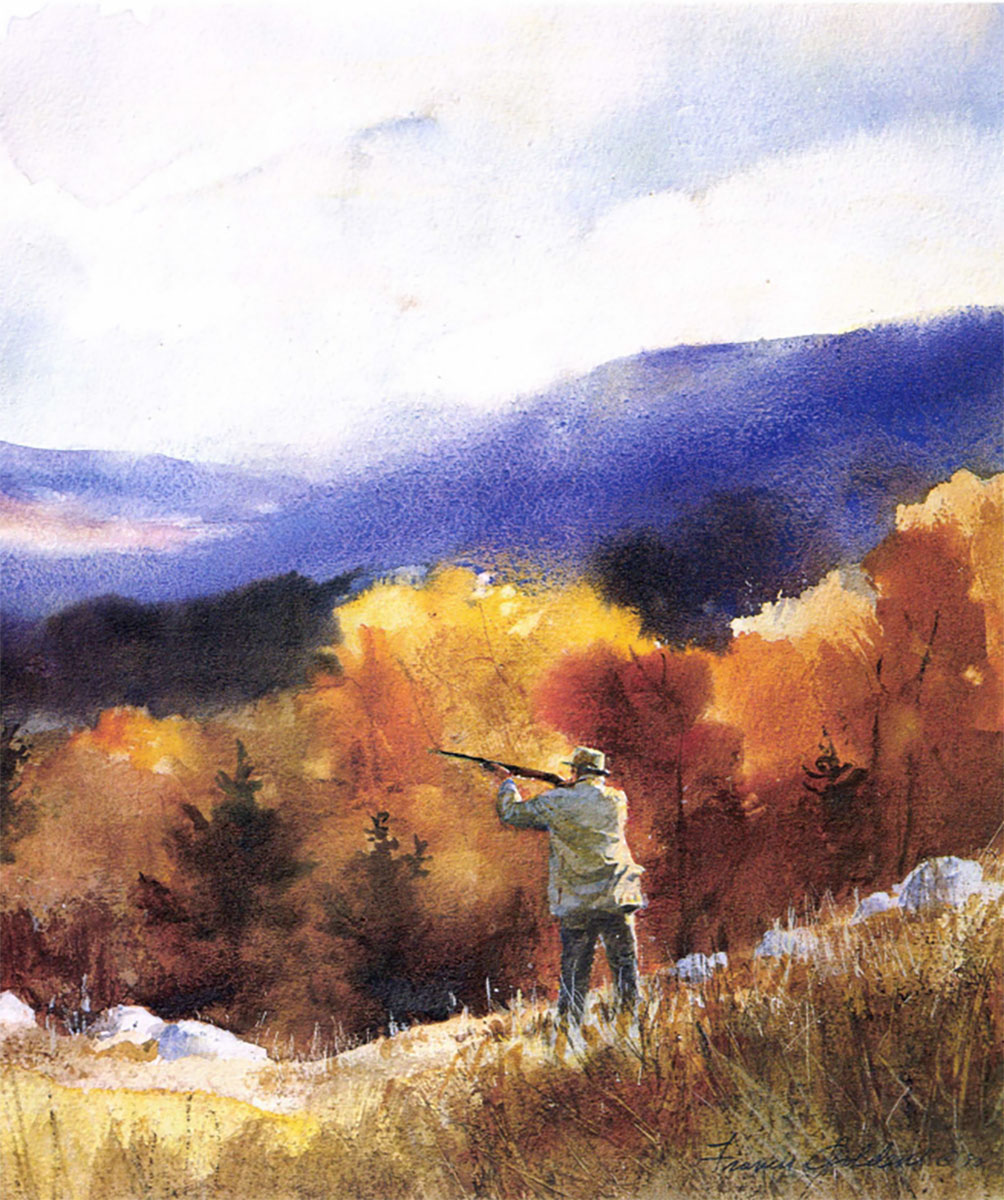

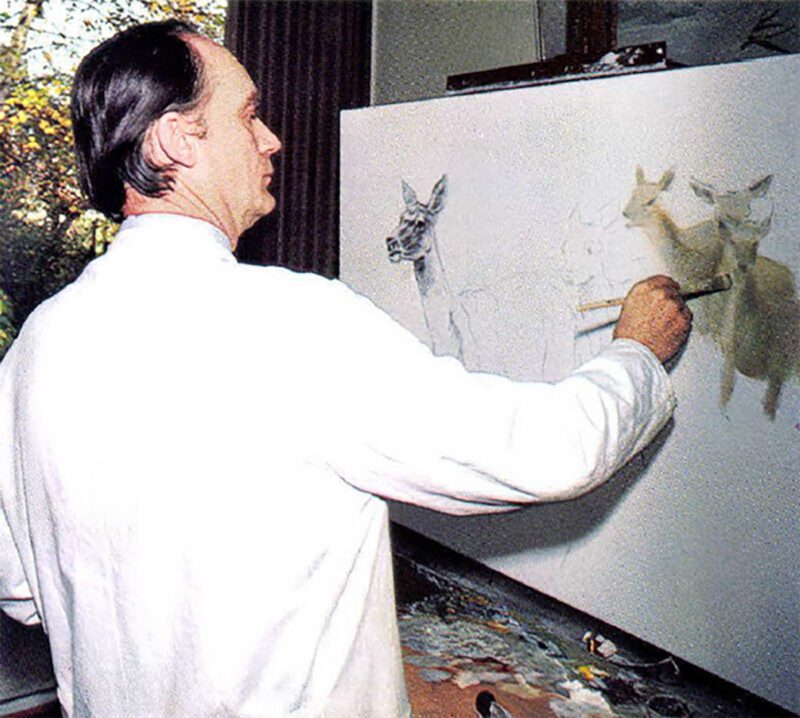

Manfred Schatz, left ,has a thorough understanding of color, composition and animal movements which allows him to translate onto canvas what a sportsman would see in the wild.

“He has the uncanny ability to translate exactly what a sportsman would see in the wiId onto a canvas,” observes Terry Shortt, himself a highly regarded Canadian bird painter. Adds acclaimed U. S. wildlife artist Guy Coheleach: “Schatz can make a European boar look like it’s exploding across the canvas. His impressionistic style may be less time consuming than more heavily-detailed work, but in many respects it is more difficult to paint. It requires a thorough understanding of color and form, of layout and composition and, of course, animal movements.”

While many artists have attempted to depict wildlife in motion, only a few have succeeded. “If a painter chooses to freeze movement, as if it were a high-speed photograph, the result is a stiffness not inherent in nature,” says David Lank, wildlife art historian from Montreal. Schatz avoids such stiffness by intentionally not painting in many details in the background and in the animals themselves. “He deliberately blurs unessential details,” adds Russell Fink, the art dealer from Virginia who represents Schatz in the United States. “When a hunter sits in a blind and watches a flock of mallards come in for a landing, he doesn’t see every feather on the birds, and Schatz believes that’s the way the creatures should be painted.”

Though the German artist is less well known in this country, his paintings and prints nevertheless are gaining acceptance from a broad range of buyers. “Sportsmen buy much of the wildlife art I stock,” notes Fink. “But the Schatz paintings are being purchased not only by hunters and fishermen, but also by fine art collectors.”

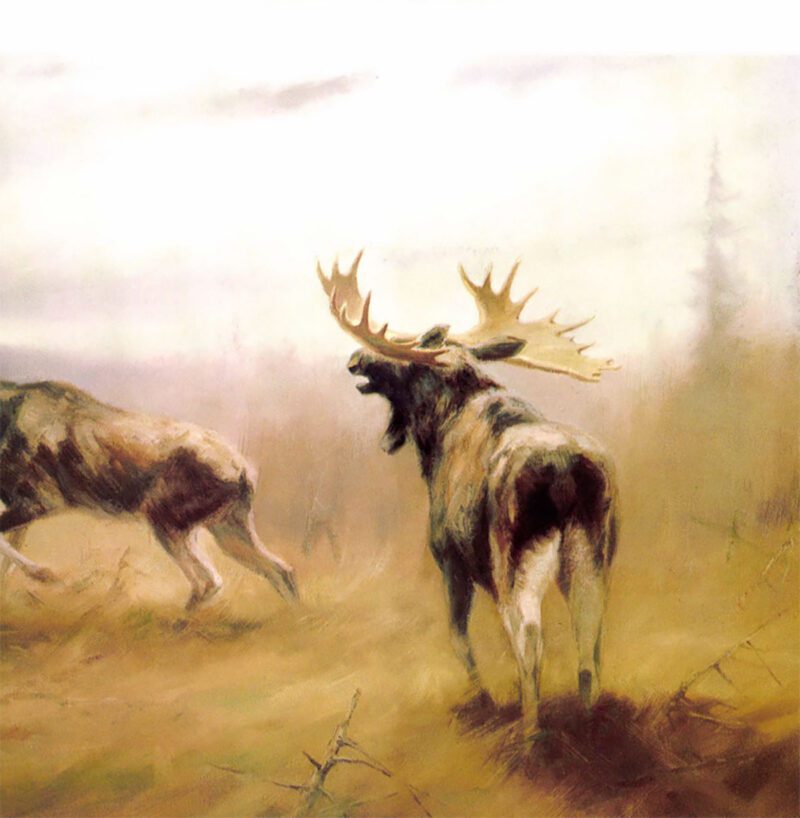

Moose (detail)

Soft-spoken, slightly built and always meticulously groomed, Manfred Schatz presents a conservative image that seems more suited to a banker or doctor than to a gifted and sometimes temperamental artist. He lives with his wife, Ilse, on a quiet street in Meerbusch, a middle-class suburb of Düsseldorf. The manicured front yard and the house itself offer few clues to the famous inhabitant. Inside, the tidy living room is decorated not with animal paintings but with portraits made by the artist of his two sons. The backyard has been left to grow wild. Tall trees dominate much of this area, surrounding a small pond and providing roosting sites for a variety of songbirds. A stone path winds through this thick growth to Manfred Schatz’s private domain: his studio.

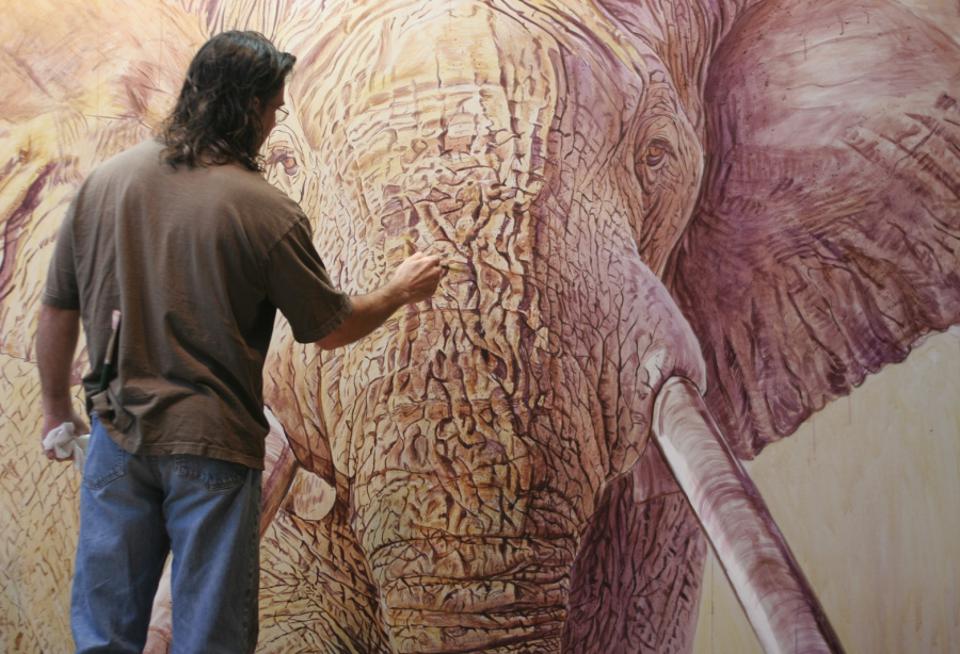

Like the artist, the studio is a model of orderliness. Hardly a smudge of paint is visible anywhere. The brushes and empty canvasses are all stacked neatly in a corner, and a steady stream of light shines in from a bank of spotless windows. All around the room, paintings line the walls — some completed and waiting for their buyers to pick them up, some still being worked on and some too precious to the artist to be sold.

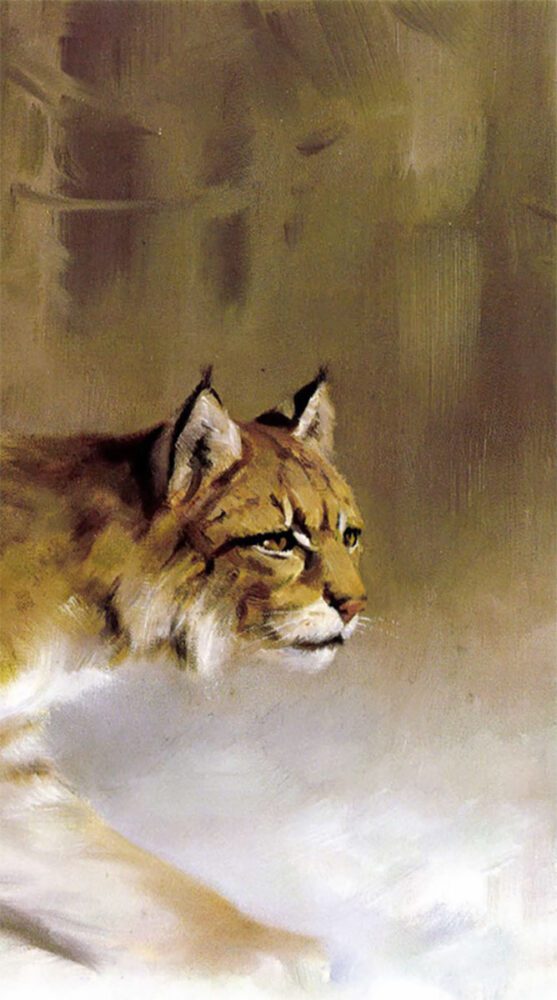

One of these, a large portrait of a lynx running through snow, is particularly special to Schatz. Several years ago, a group of fellow artists selected it as the finest painting on display at a major European exhibit. To Schatz, however, the work is significant for another reason, as well: “It captures the essence of my style,” he says. The artist has repeatedly turned down lucrative offers for it from collectors.

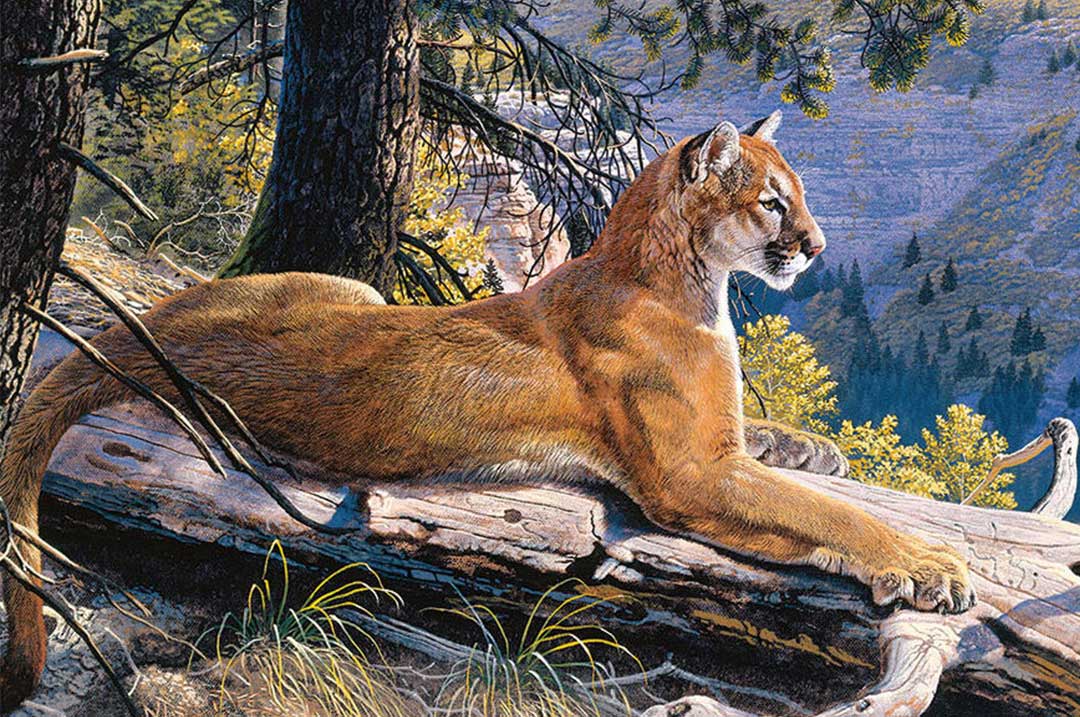

In the painting, the lynx is a blur of motion. Its paws are driving through the snow like whirlwinds, stirring wisps of the white powder into the air. Schatz intentionally used soft, sweeping brush strokes to portray most of the cat’s body. Only the head is carefully etched in detail. The result is a powerful illusion of motion. “When a lynx runs,” observes Shatz, “its head is its most prominent feature. That’s the only part of the animal’s body which doesn’t move. Everything else-including the background-is in motion, and thus appears out of focus to the human eye.”

In the painting, the lynx is a blur of motion. Its paws are driving through the snow like whirlwinds, stirring wisps of the white powder into the air. Schatz intentionally used soft, sweeping brush strokes to portray most of the cat’s body. Only the head is carefully etched in detail. The result is a powerful illusion of motion. “When a lynx runs,” observes Shatz, “its head is its most prominent feature. That’s the only part of the animal’s body which doesn’t move. Everything else-including the background-is in motion, and thus appears out of focus to the human eye.”

Like many of his paintings, this one was made only after Schatz had completed numerous field trips to northern Scandinavia to observe and sketch the cats in the wild. “Winter is the only time elusive creatures like the lynx can be followed, ” he says, “and only then if the snow is high enough to slow the animal down.”

Even within the familiar surroundings of his studio, Schatz remains a very formal person. He has narrow, unnerving eyes that never waver in their intensity. When he speaks, the words come out slowly, as if each phrase has been carefully plotted out in his mind. He rarely feels comfortable around strangers. “Manfred is really a very gentle person,” says Ilse, “but he is also very private and cautious.” Only when the conversation turns to art does the artist begin to relax. “Painting is a test — the only way I can continually challenge myself,” he notes with an air of confidence that is the result of years of critical praise.

Cougar

Manfred Schatz was born in 1925 in the village of Bad Stepenitz, in what was then eastern Germany but today is a part of Poland. His father was a well-known family portrait artist who encouraged his son to begin painting at an early age. When he was 17, Schatz became the youngest student ever accepted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin Germany’s finest school for artists. There, he first studied the technique of a group of painters who would profoundly influence his own style: the Impressionists. “By abandoning their studios and working outdoors, they changed the whole concept of painting,” says Schatz.

Not long after the teenager reported to the academy, a professor asked to see his portfolio. As the instructor leafed through the materials, he pulled several paintings out for closer inspection; all of them were drawings of circus animals Schatz had completed a few months earlier. “He suggested that I concentrate on painting animals,” recalls the artist, “but I wanted to do landscapes. His advice was bitterly disappointing.”

Near the end of World War II, Schatz was inducted into the German army and sent to the Russian Front. There, his entire company was captured and sent to a prison camp in a remote area of the Soviet Union. The artist did not see his home again for nearly five years.

Schatz rarely speaks of those years in prison. When he does, it is only with great remorse. “We had only two hot meals the entire time I was there, ” he remembers, “and those were little more than hot water with cubes of bread.”

Schatz considers the Lynx (detail), the most difficult animal he paints. Numerous trips to northern

Scandinavia to observe and

sketch these cats have enabled him to skillfully portray their elusive

nature.

To help pass the time, Schatz began drawing tiny scenes of prison life for his fellow inmates. Such sketches were against prison rules, however, and when one Russian officer intercepted a drawing, Schatz thought he was in serious trouble. But instead of punishing the artist, the officer asked him to copy a painting from a book by an old Russian master. It was a hunting scene — the first Schatz had ever painted — and soon other officers asked for copies of their own. “I repeated that painting 26 times,” he recalls. Schatz’s health deteriorated in prison and in the fall of 1949, the Russians finally released him. He returned to Germany with a severe case of tuberculosis.

Fortunately, soon after his return, Schatz was reunited with a petite, young German woman he had met before being inducted. Ilse Kray was a government technical translator from Düsseldorf who fell in love with the frail artist. They were married in 1950, and while Schatz recuperated from his illness, Ilse worked to cover their expenses.

After Schatz grew stronger, the couple moved to a large state hunting reserve in northern Germany where the artist’s brother was chief game warden. It was there that Schatz finally shook the tuberculosis. It was also there that he began hunting and painting wild animals in earnest.

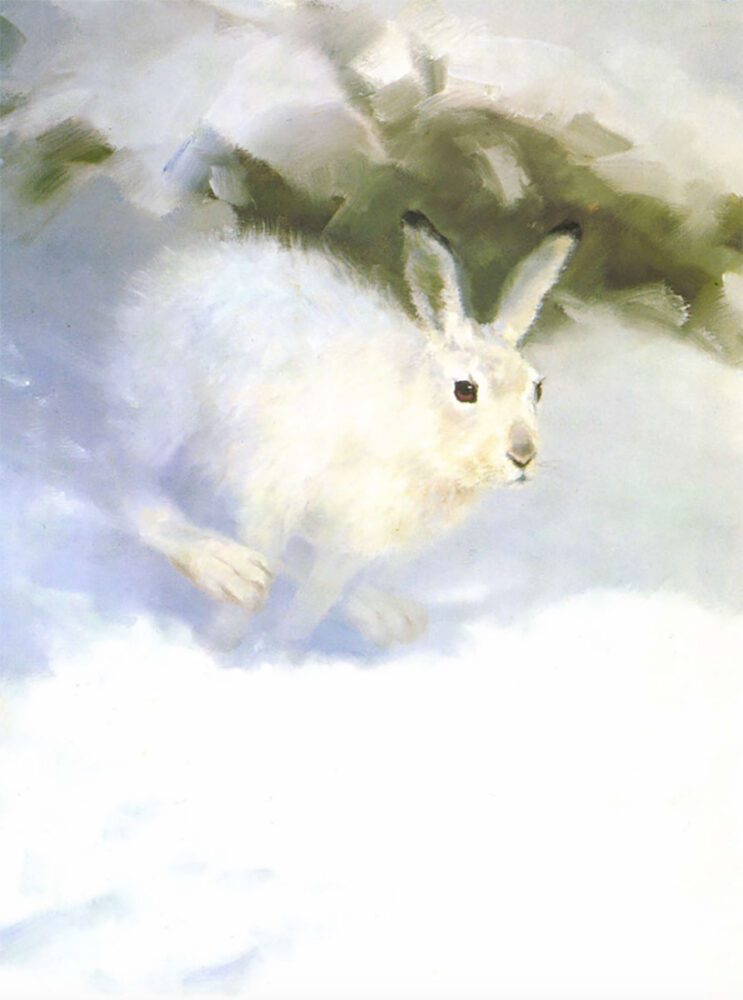

Snow Hare

“My first day at the reserve, my brother took me on his rounds and I remember seeing a flock of mallards flying up from a pond,” says Schatz. “I became hypnotized. The sight of all those birds after so many years of prison confinement so moved me that I couldn’t raise a pencil to sketch them.” Schatz thought back to his professor’s advice and returned to that spot daily. With each trip, he learned more and more details about the birds’ behavior and characteristics. “I’ve since discovered,” he adds, “that it takes years to fully understand how an animal moves, what the texture of its feathers or fur is like, where the shadows fall on its body.”

When Schatz finally left the reserve in 1951, he had made a firm commitment to studying and painting wildlife. By 1953, a West German gallery had organized the first exhibit of his work. Thirty-four paintings were displayed at that show; all but five of them were sold. Since then, he has had major exhibits in more than a dozen cities throughout the world, including New York, London and Munich. In 1975, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto put on an international exhibition entitled “Animals in Art,” which included the works of 143 artists from 25 nations. Schatz was judged the most significant artist of the exhibition.

Today, the artist divides his time between working at home in Meerbusch and visiting a cottage in southern Sweden the take-off point for expeditions to hunt and study animals in the wild. In order to sketch large mammals outdoors, he makes regular trips to Lapland, using seasoned hunting guides to help locate the creatures. “The lynx is certainly the most elusive and difficult animal I’ve painted,” says Schatz, “but the wolf may be the most fascinating to observe.”

Schatz devotes about three months of every year to fieldwork, making dozens of sketches of the animals he later intends to paint at his studio in Meerbusch. Sometimes, such outings can be extremely strenuous. On one occasion, for instance, he spent three days with a Lapp guide, following a large bull elk that was the target of a pack of wolves. “Each day,” he recalls, “there were more wolves surrounding the bull. Their attack was slow and methodical, as if carefully planned in advance. I don’t know how many sketches I made by the time the wolves finally overwhelmed the animal, but I do know that they were invaluable as reference for my efforts to recreate the event on canvas.”

Schatz devotes about three months of every year to fieldwork, making dozens of sketches of the animals he later intends to paint at his studio in Meerbusch. Sometimes, such outings can be extremely strenuous. On one occasion, for instance, he spent three days with a Lapp guide, following a large bull elk that was the target of a pack of wolves. “Each day,” he recalls, “there were more wolves surrounding the bull. Their attack was slow and methodical, as if carefully planned in advance. I don’t know how many sketches I made by the time the wolves finally overwhelmed the animal, but I do know that they were invaluable as reference for my efforts to recreate the event on canvas.”

Traditionally, many of Schatz’s field trips take place during winter. “I have always had a special attraction to snow,” he says, “perhaps because I was born during wintertime.” He has spent many hours outdoors, just looking at snow, both in sunlight and in shadows, both when old and wet or when new and powdery. “Each different condition must be painted in a different way,” he remarks.

Schatz is a master in the use of color. He rarely uses pure white when painting snow; rather he achieves the same effect by mixing together the colors found in nature like here in Polar Bears.

Such tedious field studies, many experts believe, have made Schatz a master in the use of color. “If you look very closely atone of his paintings, you’ll see that there is barely a drop of pure white paint in his snow,” notes Peter Buerschaper, head of the art department at the Royal Ontario Museum. “He gives the illusion of white by mixing together the very same colors found in nature.”

It has taken Schatz years to understand how an animal as a bird moves and what the texture of its fur or feathers is like. A hunter watching mallards land wouldn’t notice every feather and Schatz feels that is the way they should be painted.

“In general, I think what Schatz and some of the other Europeans are doing is more interesting and original than what many of the artists in this country are producing,” adds Don Eckelberry, one of the few wildlife artists ever admitted as a fellow in the American Ornithological Union (normally reserved only for scientists). “Where is it engraved in stone that you must be heavily detailed to be realistic? I consider Schatz to be just as realistic as Audubon was — not as detailed but just as realistic in terms of what the eye sees.”

American wildlife art, continues Eckelberry, is in a period of transition. “There is going to be less tight, detailed work produced here and more of the loose, impressionistic style that Schatz and other Europeans have practiced for many years,” he observes. “And why not? We have all the field guides we need right now.”

Schatz, meanwhile, is now experimenting with paintings that are even more impressionistic than those he produced in recent years. “Some of his current work is very loose, perhaps to amorphous in some cases,” says Russell Fink.

To Schatz, such criticism is valuable — and well-taken.

To Schatz, such criticism is valuable — and well-taken.

However, as he is quick to point out, his style must constantly evolve. Otherwise, painting will no longer offer a challenge.

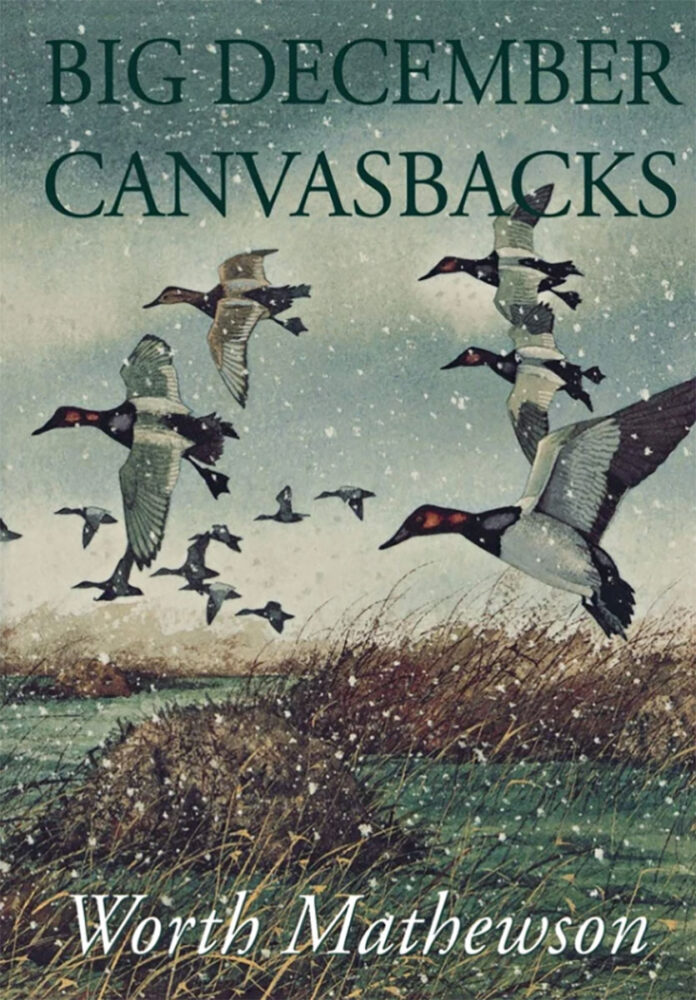

Big December Canvasbacks is a poetic celebration of the beautiful waterfowl of the northwest United States and the captivating places they inhabit. Mathewson, whose writing has regularly appeared in such publications as Field and Stream, has an uncanny ability to take us to the heart of what motivates us to pursue these beautiful animals. The book is lavishly illustrated with line art and will make the perfect gift for any waterfowler. Buy Now

Big December Canvasbacks is a poetic celebration of the beautiful waterfowl of the northwest United States and the captivating places they inhabit. Mathewson, whose writing has regularly appeared in such publications as Field and Stream, has an uncanny ability to take us to the heart of what motivates us to pursue these beautiful animals. The book is lavishly illustrated with line art and will make the perfect gift for any waterfowler. Buy Now