“I want to leave something to the imagination…some mystery in the painting. I want to leave room for a viewer to participate.”

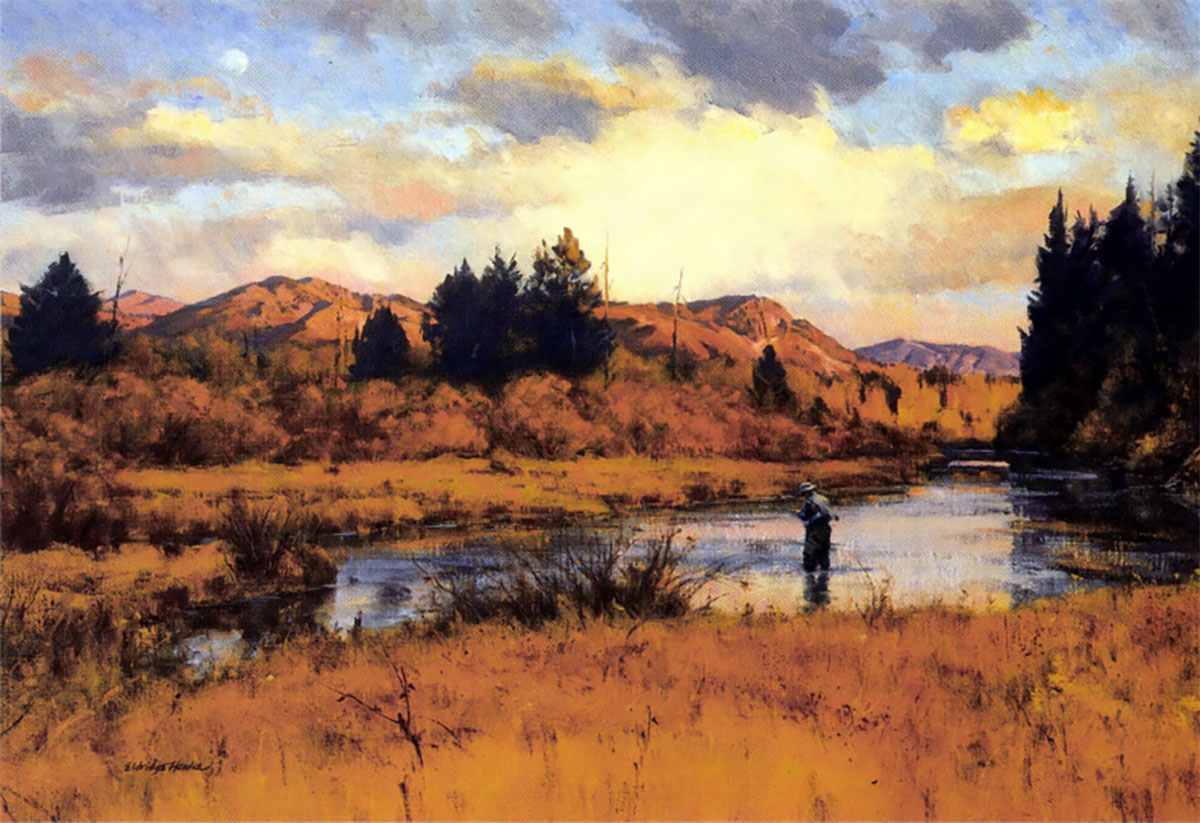

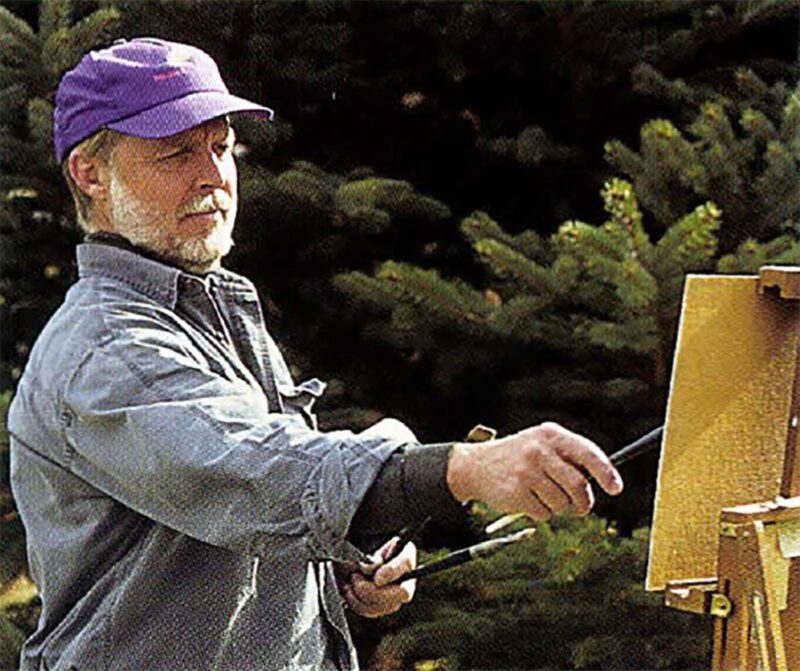

Utah artist Jim Morgan believes that painting on location is invaluable in creating a landscape that has more feeling and more spontaneity.

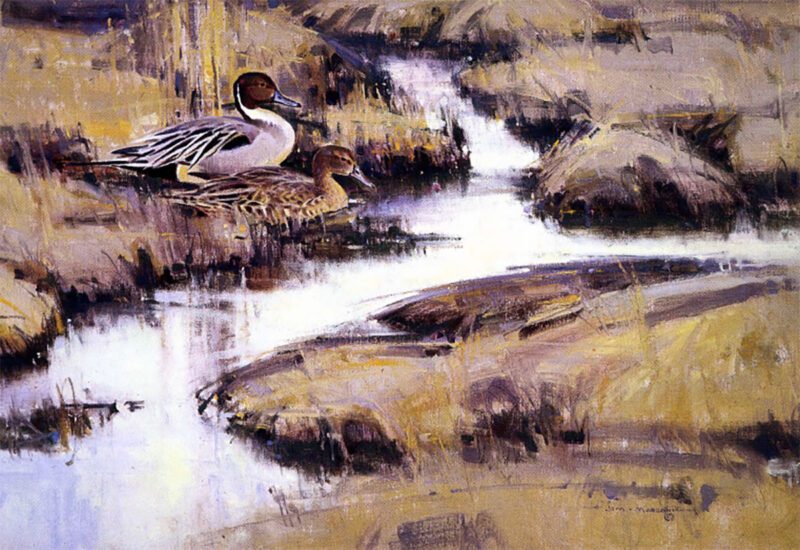

Jim Morgan reached over and picked up an old canvas goose decoy, one of several near his paint-spattered easel. His latest work-in-progress, an oil painting of pintails resting on a marsh not five miles from his northern Utah home, seemed all but finished. Before handing me the decoy, Morgan held it in his hands. The life-like bird was made from the stuffing of an old mattress, its canvas exterior sealed with bee’s wax. The decoy felt oily, almost alive.

“I bet this decoy is seventy years old,” he observed. Morgan’s father made the decoys after seeing a Utah Lake hunter use the store-bought variety. Before he died, he gave a half-dozen to each of his two sons. They looked well used.

The artist’s father was a hunter, trapper and inventor. Those skills came in handy in the tiny centra l Utah farming and mining community of Goshen. He was the kind of person who could look at something such as a boat or camper and build his own. Years later, the influence of the father on his son seems obvious.

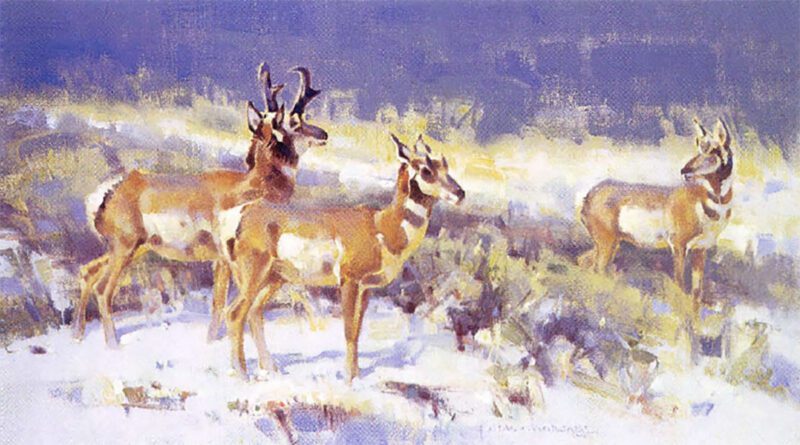

Sage Courtship — Pronghorns

“A good artist should also be an inventor,” says Morgan, nursing a cup of morning coffee while sitting on a high-legged chair. “He creates something where nothing existed before.”

Maybe that explains how Morgan’s father knew that his son possessed a talent worth nurturing. Jim started drawing when he was three. Despite the fact there was no art class at the local high school and few folks in those days thought it was possible to make a living by painting, his parents encouraged their son’s avocation.

Jim has gone on to make a good living at painting wildlife and western landscapes, though to this day, he is still challenged by his art, never quite satisfied and constantly striving to improve. Once finished with a painting, he eagerly proceeds to the next. There is little in the way of sentiment when he watches a painting go out the door to a gallery or exhibition.

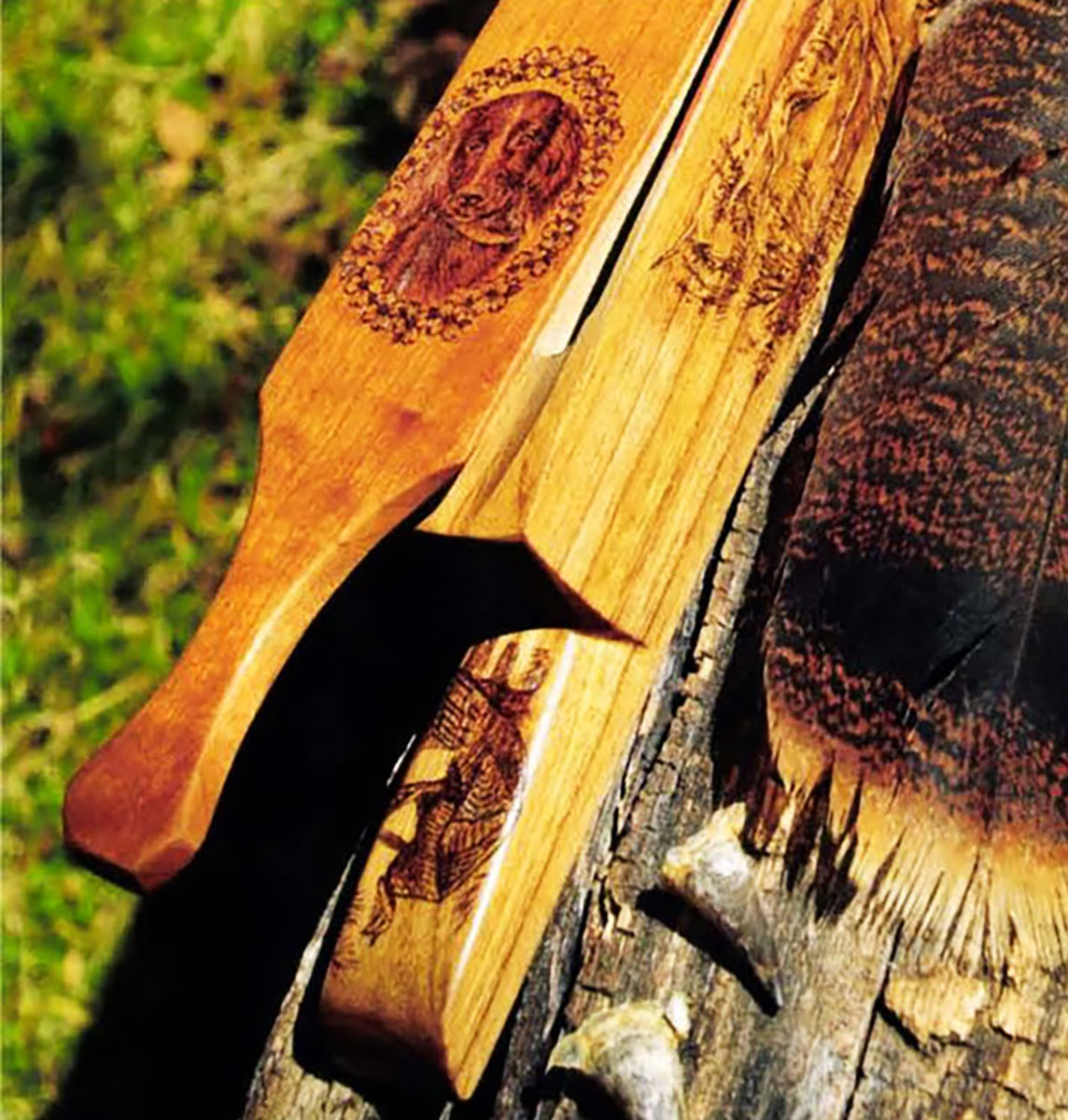

Lady of Leisure — Cougar

“I enjoy the process, but once I complete a painting, I would just as soon it went away. I’ve kept a few. The ones I think are the most successful are the ones no one else likes,” he laughs.

Some would rank Jim Morgan among the world’s best contemporary wildlife artists. His style, however, is not realistic or detailed, which has proven so popular among collectors Instead, he plays with light, brushstrokes and texture much like an impressionist. His art captures the feeling of a moment in the wild, where the movement of a well-camouflaged bird or animal might be all a hunter sees out of the corner of his eye. His colors are bright and eye-catching, and his compositions totally absorbing, whether it be a gaudy ringneck pheasant strutting out from under a snow-dappled tree or a pair of pintail ducks resting on the bank of a narrow stream.

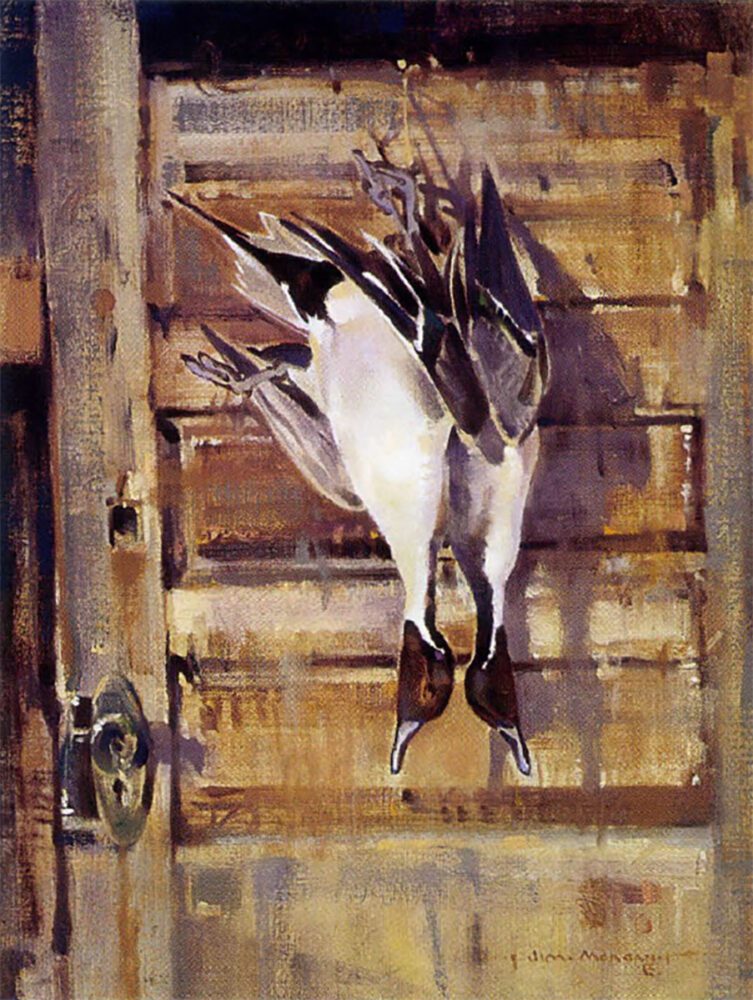

Barn Door — Pintails

Jim’s distinctive style has earned praise from his peers and many of the most prestigious exhibitions and galleries in the country. John Apgar, co-owner of JN Bartfield Galleries in New York City, one of the nation’s oldest galleries dealing in the art of the American West and wildlife, ranks Morgan among the top ten wildlife artists living today.

“There is an almost poetic quality to Jim’s art,” says Apgar. “He imparts a nice spontaneity and uses wonderful. Impressionistic colors. So many artists paint almost directly from a photograph so the finished product looks almost like a photograph Jim’s paintings are real- they look like museum pieces. Most artists try to do a portrait of an animal with little background His animals are part of an overall scene. They are landscapes with animals in them rather than just a portrait of an animal.

“Nationally acclaimed sculptor Ed Fraughton says Morgan looks at light differently than a normal person; as a result, his paintings make others appreciate what they see in the wild.” There is a freshness and a uniqueness about his work that comes through,” notes Fraughton. “You often get people who work in styles that are similar to other people He has a style of his own that is pleasing.”

Saltgrass Sultan — Pintails

Morgan lives in the tiny, store less town of Mendon at the base of the 11,000-foot Wellsville Mountains not far from Utah State University where he studied art and met his wife Ruth This is heaven for someone who loves wild places Raptors soar on wind currents high above the mountains that embrace a federally designated wilderness area. Trout streams plunge down the high-country slopes, then glide through quiet valleys sprinkled with small farms and ranches.

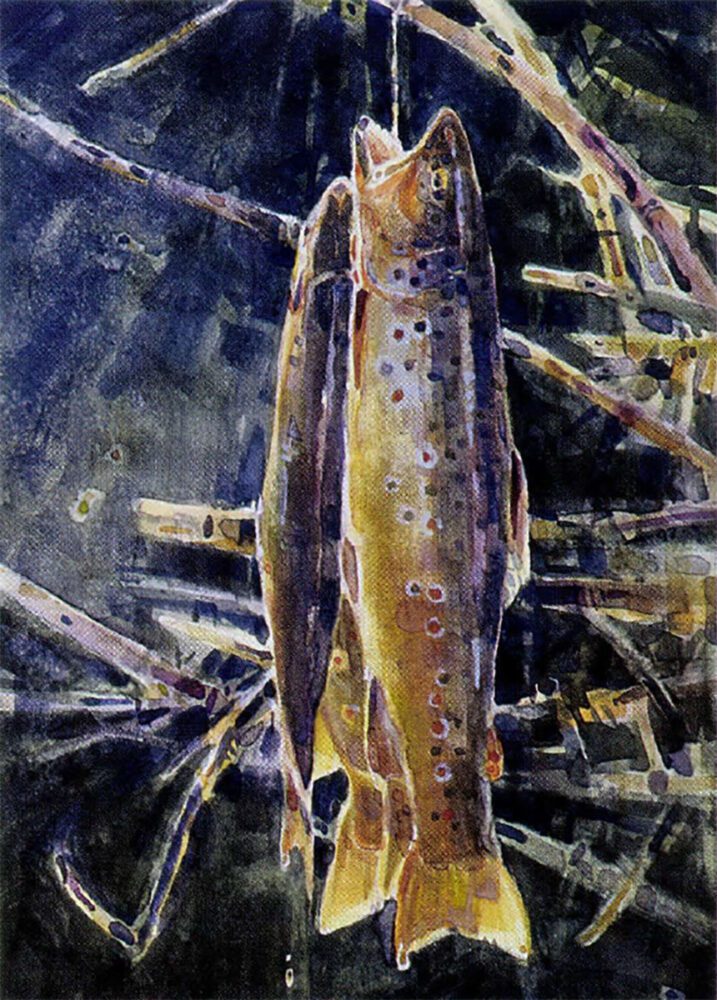

Morgan is an avid fly-fisherman, who uses flyrods that he fashioned himself, just like his father did before him. ”I’m perfectly happy catching small trout from small waters. A 12- or 14-inch brown from a six-foot-wide stream is just fine with me,” he says.

Sun Seekers — Bobwhite Quail

He takes this same, relaxed approach to hunting. “I used to be a predator back when I was attending the university. My hunting buddies and I pretty much lived off the land. Now I just like to go out and watch the dogs have fun.” Jim hunts ducks and geese on a nearby marsh with the county game warden, though in recent years he and his yellow Lab spend more hours pursuing upland game. “Our area is blessed with just about every species of game bird you can think of,” he says. “We have ruffed, blue, sage and sharptailed grouse, pheasants and Hungarian partridge — almost everything except bobwhite quail and woodcock.

The subjects of his colorful landscapes are also close by. The door of a weathered old barn next to Morgan’s home creates a background for a painting of a pair of gees he once shot. A gnarled apple tree in his neighbor’s yard has been the subject of numerous paintings. There are heron rookeries a few mils from his home. A rooster pheasant can be seen perched on the side of a nearby two-lane road, pecking at pieces of gravel.

There is a reason one seldom sees a human being in one of Morgan’s paintings. He likes to look at the world alone. And Cache County remains a good place to do just that In the winter, when snow covers the frigid valley floor, the artist waits for just the right moment, often looking out the window in a studio filled with reminders of the wild world and books filled with pain tings by his best-liked artists.

On the Rocks — Hooded Mergansers

“One of my favorite things to paint is snow and the effects of light on it,” he says. “The light can be dramatic, but still be really subtle. What I find so interesting about snow is that it’s a great simplifier. It covers unnecessary distractions, so you can concentrate on texture and patterns.”

Jim is drawn to patterns that can best be seen in the early morning twilight or at dusk. “That low light creates dramatic, long shadows. But it’ s all very fleeting You can see a certain play of light and shadow for a couple of minutes and then, that’s the end of it.”

On some afternoons, Jim will find a secluded spot in Cache Valley, where he will unfold his easel and paint oil studies of the surrounding landscape. “I don’t work plein air nearly enough, but ‘ do it whenever’ can because it’s so worthwhile for truly experiencing a time and place — the wind in your face, seeing the light and shadows slowly changing, even, I guess, putting up with mosquitoes flying into your paint. Looking into the shadows, you can see colors that you would never see in a photograph. What I take back to the studio is basically a kind of artistic shorthand with color notes that helps me create a landscape that has more feeling, more spontaneity.

“Painting on site is really just an exercise in seeing,” he points out. “That’s what art is anyway It’s being able to not just look, but to see. I try to express my impressions of a scene, not create an exact representation. “I let nature suggest what’ paint, but what’ put down on the canvas is filtered through my own experiences in the wild.”

Jim seeks to attain only a few relatively simple goals in his art. He wants to enjoy the process of painting, while generating emotional participation from those who view his work. And, he tries to bring an awareness to others of the often-overlooked and intimate aspects of nature.

“Jim is a wonderful, painterly artist, who really draws you into the scene — he gives you a strong sense of being there,” says Maryvonne Leshe, general manager and partner of Trailside Galleries. “He conveys the sense of suddenly walking up and seeing the animal, as if caught in a moment of time.”

“I want to achieve a balance between the subject and its environment,” Jim asserts. “This harmony is further aided by the play of light, shadow and subtle color changes. I am intrigued by the patterns and shapes found in nature. I concentrate on the effects of light on these elements and the resulting array of colors and nature’s ever-changing moods.”

Jim is a modest person. One can sit with him for several hours and hardly get a sense of his high standing in the art world. He does not come across as a self-promoter or someone interested in making huge amounts of money.

“Jim is a kind and gentle man, who has a tremendous sensitivity and love for painting the wildlife he knows and lives with,” adds Leshe, who has been showcasing and selling Morgan’s originals for the past eight years. “He is an artist with great personal vision and talent.”

German Browns

The only clue he might give to his stature among the best American wildlife artists is in the one-page biography he handed to me with little fanfare In it, one learns that he has won numerous awards, including the Robert M. Lougheed Memorial Award from the National Academy of Western Art in Oklahoma City; the 1996 Red Smith Artists Choice Award from the National Wildlife Art Museum in Jackson, Wyoming; The 1993 and 1995 Ben Stahl Artist’s Choice Award from the Northwest Rendezvous in Park City, Utah, and an Award of Merit from the Society of Animal Artists in New York.

Morgan, 51, plans to keep trying to learn new things. He experiments with different paints. And he has returned to his roots by doing more watercolors. He is even fooling around with sculpture, sometimes to give his paintings added perspective and sometimes in the hope of creating a different kind of art. Mostly, he laughs, his future sculptures are nothing more than blocks of clay sitting in their paper packages.

One thing is obvious. He loves the outdoors. And he enjoys looking at the wild world with the eye of an artist hunting for yet another way to express the beauty he sees.

“I want to leave something to the imagination,” he says… “some mystery in the painting. I want to leave room for a viewer to participate.”

Most of those who look at his work in books or galleries throughout the United States feel that sense of participation. Nearly all marvel at his style.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1999 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now