It has always seemed to me that any man is a better man for being a hunter.

I have said that my hunting has often been solitary; but that was chiefly in the early days. During the last 25 years, I have rarely taken to the woods and fields in the shooting season without having one or more of my own sons with me. Few human relationships are closer than those established by a mutual contact with nature; and it has always seemed to me that if more fathers were woodsmen, and would teach their sons to be likewise, most of the so-called father-and-son problems would vanish.

Providence gave me three sons, only about a year-and-a-half apart; and since it was not possible for me to give them what we usually call the advantages of wealth, I made up my mind to do my best by them. I decided primarily to make them sportsmen, for I have a conviction that to be a sportsman is a mighty long step in the direction of being a man. I thought also that if a man brings up his sons to be hunters, they will never grow away from him. Rather the passing years will only bring them closer, with a thousand happy memories of the woods and fields. Again, a hunter never sits around home forlornly, not knowing what in the world to do with his leisure. His interest in nature will be such that he can delight in every season, and he has resources within himself that will make his life always seem worthwhile.

Providence gave me three sons, only about a year-and-a-half apart; and since it was not possible for me to give them what we usually call the advantages of wealth, I made up my mind to do my best by them. I decided primarily to make them sportsmen, for I have a conviction that to be a sportsman is a mighty long step in the direction of being a man. I thought also that if a man brings up his sons to be hunters, they will never grow away from him. Rather the passing years will only bring them closer, with a thousand happy memories of the woods and fields. Again, a hunter never sits around home forlornly, not knowing what in the world to do with his leisure. His interest in nature will be such that he can delight in every season, and he has resources within himself that will make his life always seem worthwhile.

Hunters should be started early. As each one of my boys reached the age of six I gave him a single-shot .22 rifle, and I began to let him go afield with me. For a year or so I never let him load the gun, even with dust shot, but I just tried to give him some notions of how to handle it, of how to cross a ditch or a fence with it and in what direction to keep the muzzle pointed.

From the time when the first one was six years old, I could never get into my hunting clothes without hearing, “Dad, take me along!”

Sometimes an argument was added: “I will shoot straight!” To these winning pleas I have always tried to give an affirmative answer, even when I had to alternate carrying a played-out boy and a played-out puppy. But I knew that I was on the right track when I was trying to impress on the younger generation the importance of shooting straight.

I think the rod and gun better for boys than the saxophone and the fudge sundae. In the first place, there is something inherently manly and home-bred and truly American in that expression, “shooting straight.” The hunter learns that reward comes from hard work; he learns from dealing with nature that a man must have a deep respect for the great natural laws. He learns also, I think, in a far higher degree than any form of standardized amateur athletics can give him, to play the game fairly.

Most of our harmless and genuine joys in this life are those which find their source in primitive instincts. A man who follows his natural inclinations, with due deference to common sense and moderation, is usually on the right track. Now the sport of hunting is one of the most honorable of the primeval instincts of man. What human thrill is there in lounging into a grimy butcher-shop and sorrowfully surrendering a hard-earned simoleon for a dubious slab of inert beef? Certainly, any true man would far rather trudge fifteen miles in inclement weather just for a chance at a grouse. Even if he gets nothing, he will be a younger and a better man when he gets home, and with memories that will lighten the burden of the days when he cannot go afield.

A lot of good people, seeing me rearing my sons to be woodsmen, have offered me advice. “How can you love nature and yet shoot a deer?” “How can you bear to teach those children to kill things?”

These parlor naturalists and lollipop sentimentalists, whose knowledge of nature is such that they would probably take a flying buttress for a lovely gamebird, are incapable of understanding that it is far less cruel to kill a wild deer than it is to poleax a defenseless ox in a stall. The ox has no chance; but the deer has about four chances out of five against even the good hunter. Besides, I have a philosophy which teaches me that certain gamebirds and animals are apparently made to be hunted, because of their peculiar food value and because their character lends zest to the pursuit of them. It has never seemed to me to be too far-fetched to suppose that Providence placed game here for a special purpose.

Hunting is not incompatible with the deepest and most genuine love of nature. Audubon was something of a hunter; so was the famous Bachman; so were both John Muir and John Burroughs. It has always seemed to me that any man is a better man for being a hunter. This sport confers a certain constant alertness, and develops a certain ruggedness of character that, in these days of too much civilization, is refreshing; moreover, it allies us to the pioneer past. In a deep sense, this great land of ours was won for us by hunters.

Again, there is a comradeship among hunters that has always seemed to me one of the finest human relationships. When fellow sportsmen meet in the woods or fields or the lonely marshes, they meet as friends who understand each other. There is a fine democracy about all this that is a mighty wholesome thing for young people to know. As much as I do anything else in life, I measure my comradeships with old, grizzled woodsmen. Hunting alone could have made us friends. And I want my boys to go through Me making these humble contacts and learning from fellow human beings, many of them very unpretentious and Simple-hearted, some of the ancient lore of nature that is one of the very finest heritages of our race. Nature always solves her own problems; and we cml go far toward solving our own if we will listen to her teachings and consort with those who love her.

Again, there is a comradeship among hunters that has always seemed to me one of the finest human relationships. When fellow sportsmen meet in the woods or fields or the lonely marshes, they meet as friends who understand each other. There is a fine democracy about all this that is a mighty wholesome thing for young people to know. As much as I do anything else in life, I measure my comradeships with old, grizzled woodsmen. Hunting alone could have made us friends. And I want my boys to go through Me making these humble contacts and learning from fellow human beings, many of them very unpretentious and Simple-hearted, some of the ancient lore of nature that is one of the very finest heritages of our race. Nature always solves her own problems; and we cml go far toward solving our own if we will listen to her teachings and consort with those who love her.

In the case of my own boys, from the .22 rifle they graduated to the .410 shotgun; then to a 20-gauge; then a 16; then a 12. I was guide for my oldest son, Arch, when he shot his first stag. We stalked him at sundown on Bull’s Island, in the great sea-marsh of that magnificent preserve, creeping through the bulrushes and the myrtle bushes until we got in position for a shot. And that night at the clubhouse, when I went to bed late, I found my young hunter still “‘ride awake, no doubt going over our whole campaign of that memorable afternoon.

I was near my second son, Middleton, when he shot his first five stags. I saw all of them fall — and these deeds were done before he was 18.

I followed the blood-trail of the first buck shot by my youngest son, Irvine. He had let drive one barrel of his 16-gauge at this great stag in a dense pine thicket. The buck made a right-about face and headed for the river a mile away. He was running with a doe, and she went on across the water. The buck must have known that he could not make it, for he turned up the plantation avenue, actually jumped the gate, splashing it with blood and fell dead under a giant live-oak only eighty yards from the house!

It’s one thing to kill a deer, and it’s another to kill one and then have him accommodate you by running out of the wilds light up to your front steps. That kind of performance saves a lot of toting. This stag was an old swamp buck with massive antlers. Last Christmas my eldest son had only three days’ vacation; but he got two bucks.

Yes, I have brought up my three boys to be hunters; and I know full well that when the wild creatures need no longer have any apprehensions about me, my grandchildren will be hard on their trail, pursuing with keen enjoyment and wholesome passion the sport of kings. While other boys are whirling in the latest jazz or telling dubious stories on street corners, I’d like to think that mine are deep in the lonely woods, far in the silent hills, listening to another kind of music, learning a different kind of lore.

This privilege of hunting is about as fine a heritage as we have, and it needs to be passed on unsullied from father to son. There is still hope for the race when some members of it are not wholly dependent upon effete and urbane artificialities for their recreation. A true hunter will never feel at home in a nightclub. The whole thing would seem to him rather pathetic and comical somehow not in the same world with solitary fragrant woods, rushing rivers and the elegant high-born creatures of nature with which he is familiar. Hunting gives a mana sense of balance, a sanity, a comprehension of the true values of life that make vicious and crazily stimulated joy a repellent thing.

I well remember the morning when I took all three of my boys on a hunt for the first time. I had told them the night before that we were going for grouse and had to make an early start for Path Valley. There must have been a romantic appeal in the phrase “early start,” for I could hardly get them to sleep that night. And such a time as we had gotten all the guns and shells and hunting clothes ready, and a lunch packed, and the alarm clock set! And now, nine years after that memorable day, we still delight in making early starts together.

That day, before we had been in the dewy fringes of the mountain a half-hour, as we were walking abreast about 50 yards apart, we had the good fortune to flush a covey of five ruffed grouse. It was the first time that any of my boys had had a shot at this grand bird, which to my way of thinking outpoints every other gamebird in the whole world, bar none. An old cock with a heavy ruff fell to Middleton’s gun. A young cock tried to get back over Irvine’s head. It was a gallant gesture, but the little huntsman’s aim was true, and down came the prince of the woodland.

Arch and I were a little out of range for a shot on the rise, but ere long we flushed other birds, and I had the satisfaction of seeing him roll his first grouse. We were walking through some second growth, which was fairly thick. I had just been telling him that in such cover a grouse is mighty likely to go up pretty fast and steep to clear the tree-tops where, for the tiniest fraction of a split second, it will seem to pause as it checks its rise and the direction of its flight, which is to take it like a scared projectile above the forest. I had been telling Arch that the best chance under such circumstances was usually offered as the grouse got above the sprouts and seemed to hesitate.

I had just taken up my position in line when out of a tangle of fallen grapevines that had been draping a clump of sumac bushes a regal grouse roared up in front of Arch. I could see the splendid bird streaking for the sky and safety. At first, I was afraid that Arch would shoot too soon, then that he would shoot too late; either one would be like not shooting at all. But just as the cock topped the trees and tilted himself downward the gun spoke, and the tilt continued, only steeper and without control. With a heavy thud the bird dropped within my sight on the tinted leaves of the forest floor.

Fellow sportsmen will appreciate what I mean when I say that was a great day for me. When a father can see his boy follow and fairly kill our most wary and splendid gamebird, I think the Old Man has a right to feel that his son’s education is one to be proud of. I’d far rather have a son of mine able to climb a mountain and outwit the wary creatures of the wilderness than be able to dance the Brazilian busybody or be able to decide whether a lavender tie will match mauve socks. These little lisping men, these modern ruins who could not tell you the difference between a bull and a bullet — it is not in these that the hope of America, that the hope of humanity, lies.

When Arch was 13, I had him up at daybreak with me one morning in the wilds of the Tuscarora mountains. From the crest of the wooded ridge on which we were standing we could see over an immense gorge on either side and beyond them, far away over the rolling ridges, northward and southward. It was dawn of the first day, and there were many hunters in the mountains. The best chance at a turkey in that country at such a time is to take just such a stand and wait for one to fly over or perhaps to come walking warily up the slope of one of the leaf-strewn gullies. We had been standing together for about fifteen minutes and had heard some shooting to the northward of us, three ridges away, when I saw a great black shape coming toward us over the treetops.

When Arch was 13, I had him up at daybreak with me one morning in the wilds of the Tuscarora mountains. From the crest of the wooded ridge on which we were standing we could see over an immense gorge on either side and beyond them, far away over the rolling ridges, northward and southward. It was dawn of the first day, and there were many hunters in the mountains. The best chance at a turkey in that country at such a time is to take just such a stand and wait for one to fly over or perhaps to come walking warily up the slope of one of the leaf-strewn gullies. We had been standing together for about fifteen minutes and had heard some shooting to the northward of us, three ridges away, when I saw a great black shape coming toward us over the treetops.

“Here he comes, son!” I told my youthful huntsman. “Hold for his head when he gets almost over you.”

Three minutes later my boy was down on the slope of the gorge, retrieving a 19-pound gobbler, as proud as a lad could be, and entitled to be proud. It was all he could do to toil up the hill with his prize.

Irvine shot his first turkey on our plantation in Carolina. He was on a deer-stand when this old tom came running to him through the huckleberries. The great bird stood almost as tall as he did.

Middleton killed his first gobbler under peculiar circumstances. We walked into a flock together, at daybreak, and they scattered in all directions, but were too drowsy to fly far. He wounded a splendid bird, and it alighted in a tall yellow pine about a hundred yards from us. There was not enough cover to enable him to creep up to it, and the morning was so very still that I was afraid his first step would scare the tom from his lofty perch.

“I know what to do,” he whispered to me as I stood at a loss to know what to advise. “Don’t you hear that old woodpecker hammering on that dead pine? Every time he begins to rap I’m going to take an easy, soft step forward. Perhaps I can get close enough.”

“Go ahead,” I told him, and stood watching this interesting stalk.

The woodpecker proved very accommodating, and every other minute hammered loudly on the sounding tree. Step by cautious step Middleton got nearer. At last, he raised his gun, and at its report the gobbler reeled earthward. I thought the little piece of woodcraft very neatly executed.

If the sentimentalists were right, hunting would develop in men a cruelty of character. But I have found that it inculcates patience, demands discipline and iron nerve, and develops a serenity of spirit that makes for long life and long love of life. And it is my fixed conviction that if a parent can give his children a passionate and wholesome devotion to the outdoors, the fact that he cannot leave each of them a fortune does not really matter so much. They will always enjoy life in its nobler aspects without money and without price. They will worship the Creator in his mighty works. And because they know and love the natural world, they will always feel at home in the wide, sweet habitations of the Ancient Mother.

If the sentimentalists were right, hunting would develop in men a cruelty of character. But I have found that it inculcates patience, demands discipline and iron nerve, and develops a serenity of spirit that makes for long life and long love of life. And it is my fixed conviction that if a parent can give his children a passionate and wholesome devotion to the outdoors, the fact that he cannot leave each of them a fortune does not really matter so much. They will always enjoy life in its nobler aspects without money and without price. They will worship the Creator in his mighty works. And because they know and love the natural world, they will always feel at home in the wide, sweet habitations of the Ancient Mother.

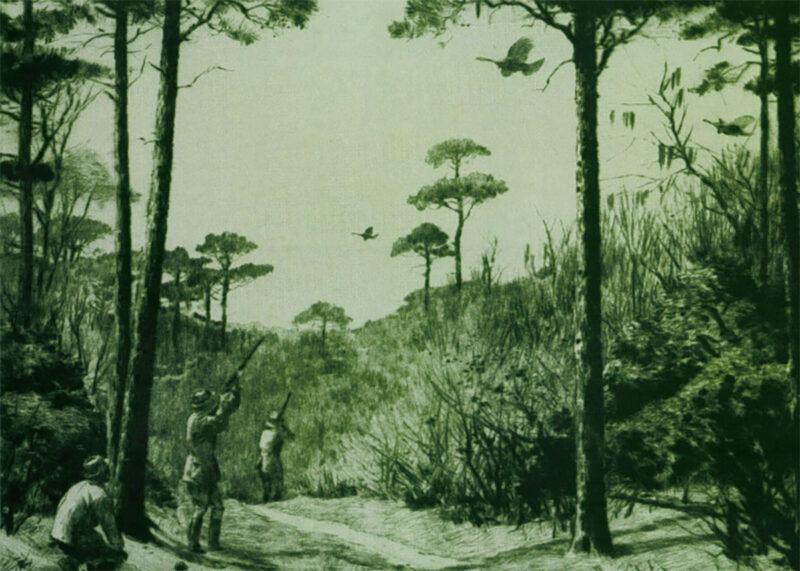

Editor’s Note: This is an edited version of Rutledge’s original story from An American Hunter in 1937. “Why I Taught My Boys to be Hunters” is among 34 stories in Hunting and Home in the Southern Heartland (1992), compiled and edited by Jim Casada. All artwork for this article courtesy of Childs’ Gallery.

During the first half of the twentieth century, Archibald Rutledge hunted wild turkeys in the woodlands surrounding his ancestral South Carolina plantation. He became wise in the ways of the wary creature and wrote prolifically about the sport. In this collection, noted outdoor writer Jim Casada gathers thirty-four of Rutledge’s finest turkey-hunting yarns. Buy Now

During the first half of the twentieth century, Archibald Rutledge hunted wild turkeys in the woodlands surrounding his ancestral South Carolina plantation. He became wise in the ways of the wary creature and wrote prolifically about the sport. In this collection, noted outdoor writer Jim Casada gathers thirty-four of Rutledge’s finest turkey-hunting yarns. Buy Now