“We had no lion tag and there was no game scout to give permission.”

Moses threw another load of sticks upon the coals. The fire crackled, sparks flew and smoke rolled. Zambia, in the valley of the Great Zambezi. Out on the sandbars, hippos were grunting up dates, a-hunka-hunka-hunka. A leopard coughed in the gathering dark and the world turned to orange and red as the sun slipped off toward Mozambique.

All these safari hands were like unionized Democrats. The skinners skinned and only skinned. The trackers only tracked and a gunbearer would not even look at the ground unless he judged the trackers bamboozled.

Moses opened and shut the kraal gate, fueled the generator and fed the fire, that’s all. Festo gathered mopane firewood, that’s all. Mopane was hard as soft iron, impossible to split but burned hotter than pig-nut hickory. Festo busted branches and sticks to usable length with an axe hand-forged from a broken truck spring— on a mopane wood fire, of course. And then Moses threw them on the fire.

“We like to keep it simple,” Ron explained. “It keeps the hands focused. And if something doesn’t get done, we know exactly who to blame. We never hire from only one family, one clan or village, either. Paying work is scarce in the bush. Spread the money around and you’ll have lots of friends.”

Ron was my PH, an Australian who landed here a dozen years before. He’d enjoyed his share of cardiac elevation, shot his share of dangerous game off clients, elephants, lions and leopards, and culled Cape buffalo when they brought hoof and mouth disease to domestic cattle. Ron shot a double rifle, 470 Nitro Express, cartridges big as your fore-finger.

We were engaged in a sacred African bush camp tradition, the sundowner, whiskey and palaver around a fire at the dying of the sun. Me and Ron, Peter the outfitter who held the hunting concession, Sarge, a Kenyan Arab who drove the safari car, a hard-sprung, open Toyota eight-seater four-wheel-drive with eight-ply rubber that would loose your fillings and stop your watch. Ron had it shipped in from Abu-Dhabi, steering wheel on the wrong side and the shift pattern backwards.

But there was something else on the wind.

“I say. Roger old chap,” Ron asked, “can you spare me a rolling paper?”

I rolled my own cigarettes. I could and I did.

Ganja, the “breath ob Gawd, mon,” is universally enjoyed in the African bush, little marbles of rock-hard green traded for a few kwacha, Zambian legal tender worth about eight U.S. cents each. But there were no rolling papers. Bush Africans used newspaper and you could trade a single pack of Zig-Zags for an ounce of ganja any day of the week just about anywhere.

The camp was on a cut-bank of the Luangwa, 20 feet down a rotten slope to the water. A hippo could not climb it and a croc might try, but it would wake up the night watchman who remained diligent till sunrise when the day watchman took over. Aside from malarial mosquitoes and ivory poachers, hippos and crocs kill far more people than the dreaded Big Five, the dangerous game quintet.

The camp’s backsides were protected by a woven wicker kraal, a seven-foot stick fence. An elephant could walk through it in his sleep, a lion could jump over it and a leopard could weasel his way underneath. But still, it was better than nothing, maybe.

“Back when we were building this camp,” Peter recalled, “we had the kitchen and the dining hall but no kraal yet. We worked all day and when we turned in, one man decided to sleep by the fire instead of inside with the rest of us. I warned him but he said our snoring would keep him awake.”

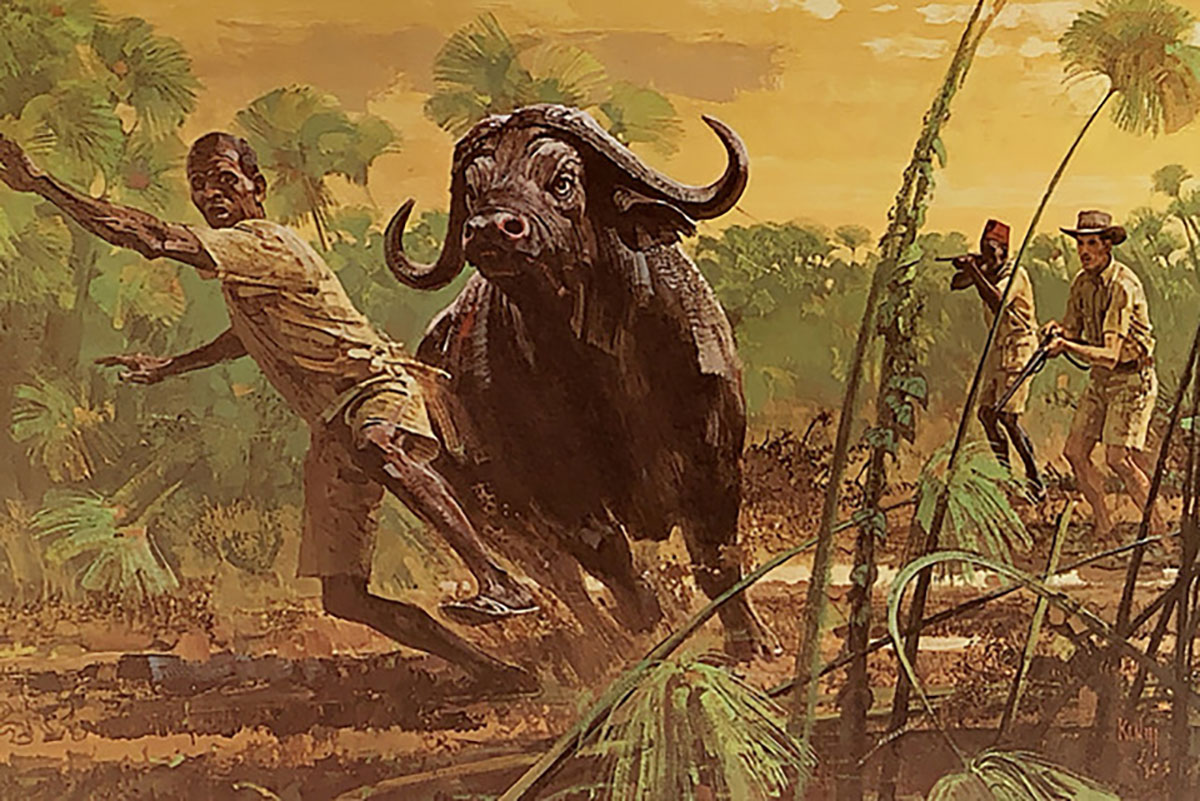

Ernest Hemingway swapping stories with legendary professional hunter Phillip Percival around a safari campfire in 1953.

“One of my exes said I snored,” I said, “so I laid awake one night to see. She was a liar, but I knew that already.”

“One of them?” Sarge asked. “You must be a wealthy man.”

Sarge was Arab, like I said.

I snorted. “You ever talk to Solomon at the Royal Pamodzi in Lusaka?”

“You mean the bell captain that looks like some Moorish admiral at Trafalgar?”

“Yep. I asked him if he was like the Solomon in the Bible, the smartest man with nine hundred wives and concubines. ‘Oh, much smarter, Bwana,’ he said. ‘I have only three.’”

Peter endured the interruption, then resumed his tale. “A couple of hours later, we heard him scream. A big male lion had him by the leg and was dragging him toward the bush.”

“Damn! You shoot him?”

“We had no lion tag and there was no game scout to give permission. And I had just obtained the concession. So we beat the lion with mopane sticks. It released the man but kept his trousers. He lost his underpants when we dragged him back to the fire. The lion turned around, came back and ran off with his those, too.”

I poured myself another dram, a stiff one, and cast an eye upon the kraal, wishing it were chain link instead of thatch, wishing it were topped with barbed wire instead of nothing.

“I believe that ain’t your one and only lion story.”

Peter shrugged, hitched his shorts, his right leg looked like a road map of Cape Town.

“My client broke his jaw in the charge, or it would have been much worse, Bwana. My father taught me three things: Never trust the bush, never trust the dark and a lion never bluff-charges. Once he comes, either you or he will die.”

Sarge’s own daddy had been taken by a croc while fishing. At least they thought it was a croc. All they found was one shoe. Sarge kept mum.

It was Ron’s turn.

“We had this German in camp and he had a leopard tag. Three nights on the bait, he never saw Mr. Spots. One afternoon the skinners came to me. ‘There is a leopard bothering us, Bwana. He tries to get into the skinning shed. Can you shoot him?’ So I asked Alex, the game scout, and he gave his permission.

“We staked a zebra skull to the ground about twenty meters before the shed, made a bed for the client on the floor, and peeled back the thatch wall for him to shoot. We all turned in and in the middle of the night, crunch, crunch, there was the leopard chewing on the zebra skull. The client poked his rifle through the thatch, shot and missed.

“We all went back to bed, confident we had seen the last of the beast, but a hour later, crunch, crunch, there it was again. The client shot and missed the second time! Surely, it would not come back a third time, but it did. This time the client killed it.

“All the hands started dancing and singing and the client joined them. Then Alex pointed and whispered, ‘Look, Bwana, look!’ And I looked and, yes, he had shat himself!”

The hippos kept up their love-sick serenade while another whiskey went around. Moses threw more sticks upon the coals and the leopard coughed again, closer this time.

A collection of the most beloved and enduring novels by Ernest Hemingway: The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and The Old Man and the Sea, as featured in the film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick on PBS. Buy Now

A collection of the most beloved and enduring novels by Ernest Hemingway: The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and The Old Man and the Sea, as featured in the film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick on PBS. Buy Now