For three seasons I helped my Aussie mates run a bowhunting camp in the most remote tropical wilderness you can imagine. Asiatic buffalo were the quarry, and we hunted by stalking. My first close encounter with the beasts told me to expect nothing but tense moments.

That initial encounter occurred during our exploratory trip to Melville Island, a huge Aboriginal reserve in the Arafura Sea north of Darwin. Companions Bill Baker, Brad Kane and Dan Smith were all seasoned bowhunters from Queensland, but none had ever killed a buffalo. As the sole Yank in the group, I’d never even seen one.

That changed quickly the first night we set out from camp to explore the unfamiliar surroundings. After a short walk down a ridgeline from the truck, we spotted a group of bachelor bulls grazing in an open area below us — two youngsters and one monster with horns that seemed to sweep out and back forever. Dan was the designated hitter. Just recovering from neck surgery, I couldn’t pull a heavy bow and was serving as a non-combatant.

As we discussed possible routes for a stalk, the wind switched and all three animals pointed their noses upward. This observation established two important points that we would see over and over — buffalo have an excellent sense of smell and their noses are their primary means of defense. At the first hint of human scent, the young bulls snorted and trotted off into the scrub. Their older companion, however, looked up the hill, lowered his head, and began to march in our direction.

As we discussed possible routes for a stalk, the wind switched and all three animals pointed their noses upward. This observation established two important points that we would see over and over — buffalo have an excellent sense of smell and their noses are their primary means of defense. At the first hint of human scent, the young bulls snorted and trotted off into the scrub. Their older companion, however, looked up the hill, lowered his head, and began to march in our direction.

Two minutes later the bull closed to within 15 yards, staring at us as if someone had just shot his dog. Dan maintained a tight grip on his bow, although the animal’s frontal angle offered no opportunity for a shot. With my arm around the nearest eucalyptus, I was busy wondering whether I could still shinny up a tree as quickly as I could when I was a kid. A backup rifle would have lessened the palpable tension in the air, but we didn’t have one. In a fit of bravado, we’d decided to leave our firearms behind.

The ensuing 20 minutes provided our introduction to what I now call the buffalo stare. The bull bored holes through us with his eyes and ran his tongue over his nostrils to help him identify our unfamiliar scent. Dan remained frozen, waiting for the bull to turn and expose his ribs, although none of us was sure that taking a shot would be a particularly good idea. Finally, something broke the spell, and the massive animal turned with a snort and cantered away.

Then we headed back to camp ahead of the lengthening shadows to wash our dry mouths out with cold beer and rethink our approach to bowhunting Asiatic buffalo.

Then we headed back to camp ahead of the lengthening shadows to wash our dry mouths out with cold beer and rethink our approach to bowhunting Asiatic buffalo.

Australia differs more from the rest of the world than any place I’ve ever visited. Among other things, no placental mammals are native to the continent. Most are marsupials like our opossum, and then there is the platypus, the world’s only egg-laying mammal. The dingo apparently derived from canine stock introduced from Asia by Malay traders. Early colonists quickly began filling in this blank spot in their new home’s fauna by importing ungulates ranging from camels to six species of deer.

The buffalo arrived from Asia in the 1820s. The idea was to domesticate them as a source of meat and hides. While that may have seemed like a good idea at the time, the huge bovines quickly proved unmanageable. Impossible to confine, they spread across the remote Northern Territory where large free-ranging populations persist to this day.

Asiatic buffalo are massive beasts, with mature bulls frequently weighing more than a ton. Their size and belligerent disposition make them a particularly challenging quarry for the bowhunter. Fortunately, the terrain proved well-suited to the close-range stalking opportunities we needed in order to kill them cleanly.

The animals usually spent the night grazing in open fields near the tideline, then moved uphill during the morning to wallow and sleep in the shade. The ridges were studded with gum trees and leafy, green cycads, which often provided cover while we maneuvered into point-blank bow range.

At that time of year—summer on our calendar but the dry winter in Australia—the land felt parched, even though we were rarely out of sight of the sea. The only fresh water was in stagnant pools in otherwise dry creek beds. The pools provided wallows for the buffalo and ambush sites for the crocodiles. Wallabies constantly exploded from underfoot, and the tree canopy rang with constant chatter from a menagerie of cockatoos and parrots.

At that time of year—summer on our calendar but the dry winter in Australia—the land felt parched, even though we were rarely out of sight of the sea. The only fresh water was in stagnant pools in otherwise dry creek beds. The pools provided wallows for the buffalo and ambush sites for the crocodiles. Wallabies constantly exploded from underfoot, and the tree canopy rang with constant chatter from a menagerie of cockatoos and parrots.

The local Aboriginal population lies on the distant western end of the island, concentrated around the village of Snake Bay. The only people inhabiting the area near our camp were Laurence and Marjorie Priddy, an Aboriginal couple with whom I became great friends. Laurence’s mother had hidden him in the bush during the period when the Australian government was separating Aboriginal children from their families and sending them to boarding schools to “civilize” them. His great woodsmanship reflected the time he’d spent living off the land.

Several years prior to our initial exploratory trip, I’d gotten to know Bill Baker and quickly recognized him as one of the best bowhunters I’d ever met. But buffalo were a curse species for him, and he’d failed to take one on several trips to mainland buffalo country. Although we really had no idea what we’d find on Melville Island, we all hoped it would provide Bill with an opportunity to break his jinx.

Several years prior to our initial exploratory trip, I’d gotten to know Bill Baker and quickly recognized him as one of the best bowhunters I’d ever met. But buffalo were a curse species for him, and he’d failed to take one on several trips to mainland buffalo country. Although we really had no idea what we’d find on Melville Island, we all hoped it would provide Bill with an opportunity to break his jinx.

And it did, although success didn’t come easily. We made a number stalks in the days following that first encounter only to have our best-laid plans unravel at the last minute for reasons ranging from capricious winds to the raucous cries from cockatoos that alerted everything in the jungle to our presence. But we’d located a dry creekbed that the buffalo used as an uphill travel route every morning while moving from the food-rich meadows near the shoreline to their bedding areas on a shaded ridge. And that’s where Bill finally overcame his curse.

During the fourth morning on the island we worked slowly downhill into a reliable sea breeze and let a huge mob of cows, calves, and young bulls pass us in the scrub—some so close I could have touched them. But I suspected that a mature bull would be bringing up the rear, and I was right. Bill made a cautious, well-executed stalk to 20 yards, only to have dense brush deny him a clear shot. That’s when the bull noticed him, and another buffalo stare-down began.

By this time the bull was facing Bill, eliminating the possibility of a shot. Frontal shots with a bow are a bad idea on any big game animal, especially a one-ton beast with thick hide and heavy ribs between the arrow and the boiler room. Neither hunter nor hunted moved and neither did I, for 30 minutes by my watch. You never know how hard it is to remain frozen in one position for half an hour until you’ve had to do it.

By this time the bull was facing Bill, eliminating the possibility of a shot. Frontal shots with a bow are a bad idea on any big game animal, especially a one-ton beast with thick hide and heavy ribs between the arrow and the boiler room. Neither hunter nor hunted moved and neither did I, for 30 minutes by my watch. You never know how hard it is to remain frozen in one position for half an hour until you’ve had to do it.

Finally, the buffalo had had enough. But instead of spinning and running off as we’d seen others do, he made a leisurely turn and showed his ribcage. Big mistake. Bill’s recurve sent an arrow straight into the bull’s heart, and soon we were up to our armpits in the team’s first buffalo.

I admit that it felt odd to make that initial trip while unable to hunt, but I still enjoyed the experience. Among other things, I fed camp with barramundi taken with my fly rod, dodged a few saltwater crocodiles, and learned a lot about an exotic, unfamiliar habitat. I also learned a lot about Asiatic buffalo, knowledge that would prove highly useful when I returned the following year with a bow and doctor’s clearance to use it.

After being limited to observer status on the first trip, I wasn’t feeling particularly picky about horn size once I returned with a bow in my hand. We arrived in camp to find a crocodile lying next to the barbie. Exhausted by travel, I tumbled into bed as soon as we chased him back into the creek. Cockatoos woke the camp at dawn, and we headed for a long meadow where we’d found lots of buffalo the year before.

When I spotted a mature bull grazing in an open field, I decided to try the stalk despite the lack of cover. The grass, though, obscured his vision when he put his head down to feed, and that’s when I moved. It took me nearly an hour to approach within 20 yards, at which point I simply needed the bull to turn broadside. Unfortunately, that’s when he noticed me, initiating another buffalo stare.

When I spotted a mature bull grazing in an open field, I decided to try the stalk despite the lack of cover. The grass, though, obscured his vision when he put his head down to feed, and that’s when I moved. It took me nearly an hour to approach within 20 yards, at which point I simply needed the bull to turn broadside. Unfortunately, that’s when he noticed me, initiating another buffalo stare.

I spent an uncomfortable 20 minutes fighting cramps and muscle fatigue, moving nothing but my eyes. Fortunately, the breeze remained steady in my face. When the bull finally dismissed me and started to feed again, he actually came toward me. The animal was plenty close enough, but I still needed him to turn. When he did, I sent a heavy arrow on its way and watched the bull collapse in plain sight a few seconds later.

Because of their size, thick hide, and heavy bones, buffalo make an imposing target for an arrow, and I’ve listened to a lot of discussion about what constitutes adequate tackle to kill one cleanly. Draw weight is usually the first topic in the conversation, but after lots of experience I’ve decided this is one of the least important variables when choosing archery tackle for a buffalo hunt.

Because of their size, thick hide, and heavy bones, buffalo make an imposing target for an arrow, and I’ve listened to a lot of discussion about what constitutes adequate tackle to kill one cleanly. Draw weight is usually the first topic in the conversation, but after lots of experience I’ve decided this is one of the least important variables when choosing archery tackle for a buffalo hunt.

In preparation for my first trip, I’d worked my way up to 90-pound limbs for my recurve before an unexpected neck surgery put an end to that. As I acquired more experience, I went to progressively lighter bows on each return trip, to 78 pounds and then to 72. Sharp, fixed-blade broadheads and heavy arrows are much more important than stout bows. On these hunts I always carried shafts made from Brazilian walnut that weighed more than 1000 grains.

Above all, shot placement is more important than tackle, as I saw several hunters learn the hard way. A buffalo’s vitals are located well forward, and the arrow needs to be placed tightly behind the shoulder with the animal perfectly broadside or slightly quartering away. Shots even a few inches back of the shoulder crease might produce a clean kill on a moose or an elk but will hit nothing but partially digested grass on a buffalo.

I’ll summarize my views on the subject with a simple statistic. Of some three dozen encounters between buffalo and arrows that I either witnessed or initiated, every properly placed arrow delivered at the correct angle resulted in a clean kill, no matter how light the draw weight of the bow. (Bill killed one with a 65-pound recurve.) And with one lucky exception (an arrow that struck the animal at the base of the neck), every shot that resulted in any other kind of hit led to a lost buffalo, no matter how heavy the bow.

Fortunately, the combination of good stalking cover and animals that receive virtually no hunting pressure made it fairly easy to get close enough to launch a lethal arrow, as demonstrated by the bull I killed during my third trip to the area.

Fortunately, the combination of good stalking cover and animals that receive virtually no hunting pressure made it fairly easy to get close enough to launch a lethal arrow, as demonstrated by the bull I killed during my third trip to the area.

Fickle winds spoiled a couple of stalks that morning, but we spotted a lone bull plodding downwind along a well-defined pad through the scrub. We knew where the trail led, and a high-speed walk eventually brought us into what we thought would be a good position for an ambush. In fact, it was almost too good. The moment we arrived the bull appeared out of the jungle, and I barely had time to crouch behind a cycad and nock an arrow before he was right on top of me. Timing my draw so that he was bringing his near leg forward when I released, I sent an arrow through his chest from a range of three yards. Moments later he collapsed in plain sight barely 50 yards from where I’d shot him.

Asiatic buffalo readily invite comparison with another large bovid—the Cape buffalo of southern Africa. Physically they’re quite similar, although the Cape buffalo carries a bit more weight in its front quarters. And—a point of particular interest to bowhunters—the ribs of both species lie very close together. It’s almost impossible to drive a broadhead into a buffalo’s chest without hitting bone—a good argument in favor of the heavy arrows and sharp, fixed blade broadheads mentioned earlier.

Although buffalo can and do kill people in Australia, I think Asiatic buffalo lack the malignant personality of their African counterparts. I’ve never killed a Cape buffalo but have spent considerable time around them, and I would have to think long and hard about shooting an arrow into one from a range of three yards.

Amidst all the talk of bowhunting dangerous game, it’s easy to lose sight of one of this hunt’s most memorable aspects—the tropical wilderness where Asiatic buffalo live. The uninhabited far end of the island where we hunted looked like the kind of place where Robinson Crusoe might have washed ashore. Fly-fishing for barramundi and other game fish was fantastic, and the huge saltwater crocodiles are the most imposing creatures I’ve seen anywhere on earth. The exotic birdlife in the canopy overhead had me thumbing through my reference book every day.

Due to complex local political changes, there’s no hunting on the island now, though buffalo remain abundant throughout the Northern Territory mainland and hunting opportunities abound. Furthermore, Bill Baker died of cancer before his time during the last year I visited Australia, and the place just wouldn’t be the same without him. I can’t count the number of people who told me they wanted to hunt buffalo with us . . . someday.

Due to complex local political changes, there’s no hunting on the island now, though buffalo remain abundant throughout the Northern Territory mainland and hunting opportunities abound. Furthermore, Bill Baker died of cancer before his time during the last year I visited Australia, and the place just wouldn’t be the same without him. I can’t count the number of people who told me they wanted to hunt buffalo with us . . . someday.

I’m glad I was crazy enough to make my own someday happen while I could.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 2015 Jan/Feb issue of Sporting Classics.

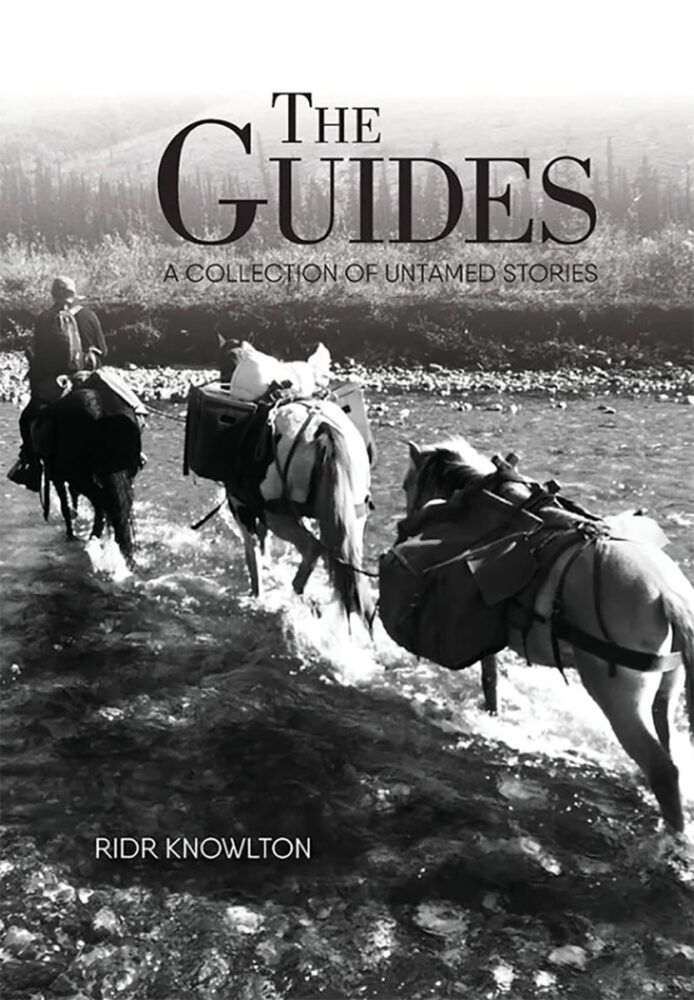

These stories are not about the game hunted or the fish caught. They are about everything else a sportsperson experiences in the field: the environment, the weather, the wildlife and (especially) the people who create lasting memories by putting the “wild” in wilderness. Buy Now

These stories are not about the game hunted or the fish caught. They are about everything else a sportsperson experiences in the field: the environment, the weather, the wildlife and (especially) the people who create lasting memories by putting the “wild” in wilderness. Buy Now