Morgan Hillard Tracked the grizzly 90 miles by following prints and carnage left in its wake.

Three miners dead; torn limbs and partly consumed bodies, grieving widows and children, and a horde of hunters now camped near “the meeting of the rivers,” a place named by the Salish Indians where the Bitterroot and Blackfoot flow into the Clark Fork of the Columbia. It was gray light of dawn; the moon going down like a large sliver of ice above a plateau covered with ponderosa pine. Below him, the Clark glowed with a black metallic light in the moon’s reflection as steam boiled off boulders exposed in the current.

Three miners dead; torn limbs and partly consumed bodies, grieving widows and children, and a horde of hunters now camped near “the meeting of the rivers,” a place named by the Salish Indians where the Bitterroot and Blackfoot flow into the Clark Fork of the Columbia. It was gray light of dawn; the moon going down like a large sliver of ice above a plateau covered with ponderosa pine. Below him, the Clark glowed with a black metallic light in the moon’s reflection as steam boiled off boulders exposed in the current.

It was the spring of 1898 and 30 hard-looking men, each toting a long rifle, sat on bedrolls or squatted on their haunches around a large tree stump. Gray canvas tents were strewn along the Clark where squaws charged $3 to milk the juices out of drunk, smelly cow hands, loggers, miners and drifters, old and young men hurting from too much rot-gut whiskey, brawling, cavorting and little sleep.

From his place in trees above the two rivers, Morgan had no trouble seeing or hearing the sheriff who stood on the stump, a thin, small-boned, capable lawman from Missoula with a Colt revolver that came out lightning-quick, it was said.

“That old griz has killed and chewed apart three men so far,” he began. “Little Bit tracked him south as far as the Bitterroots, and then came here. There’s a $500 reward for anyone that brings him in dead. He’s a man-killer and has to be put under.”

There were grunts and hawked-up spit from the dregs of throats, and brown streams of chewed tobacco splattered frozen ground as the men assessed the money amount and the time it would take to earn it. And then there was the weather and Bitterroot Mountains to think about.

“I’m limiting the hunt to six men. Form a line on Little Bit and I’ll do the picking.”

Satanka, Morgan’s blue mustang was saddled; he’d washed, eaten and had his coffee. His blanket and change of cloths were rolled inside his slicker, saddlebags packed with razor, soap, Almanac, salted pork, two cooked prairie chickens wrapped in butcher paper and burlap, tin plate, cup, fork and spoon, a small cook pot, matches and a box of .44 rounds. He put on his Stetson, flat crowned with a four-inch brim, wool shirt, vest, canvas pants and chaps that had turned black from animal grease and wood-smoke, hung his .44 Navy revolver in a light-hand draw, tied-down holster, levered a shell into the chamber of the Henry rifle, tied the bedroll to the back of the saddle, donned his duster, swung up and angled down the slope through dead and dying campfires, lipping up tent ropes, and riding through litter and sub-humans that called themselves hunters, scattering the men in all directions like quail until he stopped in front of the sheriff.

Satanka, Morgan’s blue mustang was saddled; he’d washed, eaten and had his coffee. His blanket and change of cloths were rolled inside his slicker, saddlebags packed with razor, soap, Almanac, salted pork, two cooked prairie chickens wrapped in butcher paper and burlap, tin plate, cup, fork and spoon, a small cook pot, matches and a box of .44 rounds. He put on his Stetson, flat crowned with a four-inch brim, wool shirt, vest, canvas pants and chaps that had turned black from animal grease and wood-smoke, hung his .44 Navy revolver in a light-hand draw, tied-down holster, levered a shell into the chamber of the Henry rifle, tied the bedroll to the back of the saddle, donned his duster, swung up and angled down the slope through dead and dying campfires, lipping up tent ropes, and riding through litter and sub-humans that called themselves hunters, scattering the men in all directions like quail until he stopped in front of the sheriff.

His voice came out flat like the sound of a cocked trigger. “I tracked that bear this far, reckon I’ll see it to the end without no help from this scum that call themselves hunters. That griz deserves to be put down proper.”

Sheriff Nettles took in the man he knew; black eyes the size of marbles set deep in his Scottish face, wild tangle of black hair flecked with gray sticking out from under his hat brim and below his shirt collar in back, but his flat chest as hard as a boiler plate, wide shoulders, washboard stomach, arms as big as wagon hubs and ham-like fists that looked to have the texture of buffalo hide. Looking at him would lead a man to believe him younger than his 50-plus years.

“Hard words, Morgan. I say who goes after the bear.”

His eyes caught and impaled the sheriff — hunter’s eyes rimmed with quivering energy as though he was hearing the sound of the unseen grizzly far out on the wind.

“Not from this crowd, Nettles. That griz has got a bullet in him; made him crazy with pain. Bastard that shot him didn’t have the guts to track and finish the job. Probably one of these heathens calls themselves hunters done it.

“Nettles suddenly had a better handle on why the grizzly was attacking anyone in its path. “You have proof he was shot? Little Bit said nothing about it.”

Morgan reached in a duster pocket and flipped an empty brass casing toward Nettles. “Found this and then tracked to his blood. He’s hit all right. And that Indian you call Little Bit ain’t all he’s stacked up to be. He tracked the griz to the Bitterroots, but that bear trailed him back here and crossed north over the Clark no more than a half mile from where these bastards are camped, a night ago.”

Nettles sighed, and locked eyes with the seated rider. “Last time I saw you, Morgan, you was afoot. That’s a damn fine-looking mustang. Where did you get it?” Morgan smiled, if the thin crease that moved his lips the width of a grouse feather could be called one. “Northern Cheyenne buck didn’t need her anymore.” He watched the sheriff for a reaction or explanation; saw nor heard none and went on. “She’s called Satanka, and that’s an Indian woman’s name for medicine dancer, and Nettles, she’s smart, light and fast on her feet. She’ll take me to the griz.” A hunter named Brody stepped in front of the mustang. “Now hold on. He said six men, Mister. You ain’t in charge here. That’s money anyone of us could use. The Lord knows that for sure.”

Nettles sighed, and locked eyes with the seated rider. “Last time I saw you, Morgan, you was afoot. That’s a damn fine-looking mustang. Where did you get it?” Morgan smiled, if the thin crease that moved his lips the width of a grouse feather could be called one. “Northern Cheyenne buck didn’t need her anymore.” He watched the sheriff for a reaction or explanation; saw nor heard none and went on. “She’s called Satanka, and that’s an Indian woman’s name for medicine dancer, and Nettles, she’s smart, light and fast on her feet. She’ll take me to the griz.” A hunter named Brody stepped in front of the mustang. “Now hold on. He said six men, Mister. You ain’t in charge here. That’s money anyone of us could use. The Lord knows that for sure.”

Morgan eyed the man. “You look about three quarts low, old-timer. Better get back to drinking and leave the huntin’ to me. Reckon the earth and things on it was put here for a purpose to nurture and sustain us. All of it gifts from the Lord, and that grizzly is like he is now on account of man, and that just ain’t right.”

Nettles smiled. “Brody, he’s right. If I sent six of you out, you’re so hung over, half of you would have shot the other half before sundown. It’s yours to do, Morgan.”

Without as much as a head nod, Morgan touched knees to Satanka ,turned her north away from the Clarkto cut into the tracks of the grizzly following the Blackfoot through lake country and meadowland and humped green foothills, a purple haze to the north mountains and old growth trees that were so tall they looked as if they touched the sky.

Morgan smelled the heavy, cold odor of the Blackfoot and the wetness of boulders in deep shadows along its banks, the prints of the bear drawing him east and north up-stream into hard country.

People bothered him; the country was filling up with settlers and that angered him. He could hardly go a day without bumping into a nester, miner, railroad man or cowboy wandering across Montana Territory, leaving trash in their passing.

He’d left the Bozeman jail afoot a month ago after another barroom brawl. A terrifying experience to his adversaries and a beautiful thing to watch as he stood with his back to a wall, ham-like fists cracking bone and bringing up welts as blood ran off his head and face.

The judge’s warning had shaken him. “One more altercation in Montana Territory Morgan, and you’re going to prison, locked up so you can’t do anyone harm but yourself,” Judge Grimes had said.

He didn’t belong anywhere anymore, couldn’t find peace unless he was far out in back country, and that was getting hard to find. Maybe he’d head north. That night, dry lightning rippled through thunderclouds that sealed the Blackfoot valley. The wind was up and trees shook along the riverbank, scattering dead pine needles across the water. This would be the time for the grizzly to attack, he thought, but the mustang would warn him of man or beast long before they got to him.

He didn’t belong anywhere anymore, couldn’t find peace unless he was far out in back country, and that was getting hard to find. Maybe he’d head north. That night, dry lightning rippled through thunderclouds that sealed the Blackfoot valley. The wind was up and trees shook along the riverbank, scattering dead pine needles across the water. This would be the time for the grizzly to attack, he thought, but the mustang would warn him of man or beast long before they got to him.

Toward morning, bolts of lightning crashed on the ridges up Blackfoot canyon, bursting the tips of pines into small fires that flared and drowned in rain. By noon the storm had passed, the rain stopped and the sun came out.

Then the griz was there, cutting down out of timber on Morgan’s side of the Blackfoot, wading into the river and swimming across the deepest part, the current carrying the bear west past Morgan until he lumbered belly-deep into shallow water on the north side and walked dripping up the bank into a stand of timber.

Morgan rode upstream, turned the horse into the river and slid off the saddle when Satanka had to swim, holding onto the saddle with one hand while keeping the rifle above his head until he reached shallows where he lead the horse up the bank.

He unsaddled the blue mustang, removed bit and reins, unloaded the beans in the wheel of the Navy, drying it and bullets before reloading, levered a shell into the chamber of his Henry and crept forward. Had the bear seen him? Was it a trap?

Ponderosa pines ran a mile wide and extended up Blackfoot canyon more than five miles. Man and bear in among trees now, some as big across as a wagon, virgin timber with animal trails through. Morgan could smell the bear — close, he thought.

He knew Sheriff Nettles had sent Little Bit to trail him, far back, to see how it fell and then report back. With that much money, it had to be the right griz, and the old Nez Perce Indian had seen it and knew its track.

The dead Northern Cheyenne who’d tried to steal his rifle and belongings; and the judge’s warning wore heavy on him. Morgan couldn’t stand the thought of prison. Thirty-day jail sentences were his limit.

The dead Northern Cheyenne who’d tried to steal his rifle and belongings; and the judge’s warning wore heavy on him. Morgan couldn’t stand the thought of prison. Thirty-day jail sentences were his limit.

He’d thought it through: Take the griz on face to face, and now it was all winding down like a clock pendulum swinging. How would the bear come at him? He knew how he wanted it to happen as he crept forward, legs bent, eyes touching every tree and bush as he edged past downed logs with scrub pines scattered about, all dying from lack of sun, so dense the forest he was in.

And then he was there, standing on his back legs, froth formed around his lips, front paws up, eyes red-rimmed and locked on Morgan, nostrils flared to test the wind. The bear let out a growl that would make a man weak in the knees, dropped down on all fours and swung his massive head from side to side, teeth clicking together as he tried to scent the man.

Morgan straightened, raised his arms above his head and sent forth his own growl as he stepped forward, hoping the bear would rise again. It did, and something primeval clicked in Morgan Hilliard’s head. He dropped the Henry, drew his Navy and rushed forward until his head slammed into the bear’s chest, the revolver working through all six cylinders, his whole life rushing past his eyes as bullets shattered the giant’s heart. The bear’s jaws bit together, cracking bones in Morgan’s head, both dead on their feet as the man-killer fell forward on top of him.

Little Bit caught the blue mustang and retrieved the Henry rifle. He spent a few more minutes “at the place where two giants met and fought,” then left them as he found them. He offered a prayer to the Great Spirit that the hunters would travel good paths in the other life and then rode back to report.

Little Bit caught the blue mustang and retrieved the Henry rifle. He spent a few more minutes “at the place where two giants met and fought,” then left them as he found them. He offered a prayer to the Great Spirit that the hunters would travel good paths in the other life and then rode back to report.

After telling Sheriff Nettles what he’d found, Little Bit looked off into the distant mountains and said, “He was a man. I shall not look upon his kind again.”

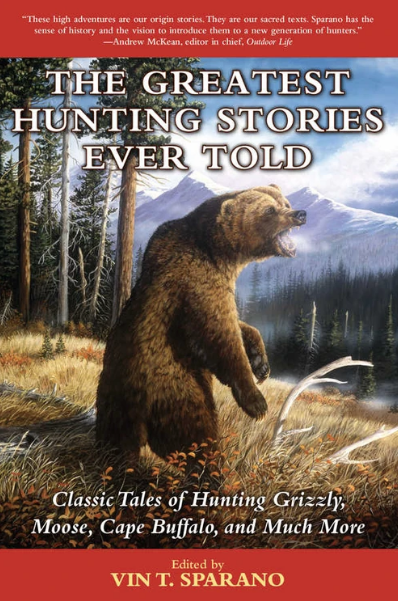

Elephant. Bear. Moose. Rhinoceros. Buffalo. Lion. Since prehistoric times man has hunted. An elemental part of life, seeking out and overpowering large, strong, and fast animals has been a pivotal part of human evolution.

Elephant. Bear. Moose. Rhinoceros. Buffalo. Lion. Since prehistoric times man has hunted. An elemental part of life, seeking out and overpowering large, strong, and fast animals has been a pivotal part of human evolution.

In later times, when hunting for food wasn’t necessary, man still tracked down his prey. Following an instinct for adventure, for the thrill of defeating formidable opponents, man hunted.

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Buy Now