All grown up and reputable now, it’s time to be proper, to forget about catchin’ carp and all those boyhood memories, back when a Zero bar cost a nickel.

I wish I wasn’t so sophisticated as I am, so I could just haul off in the daylight and find me a good carp pond again, like once we did when I was young enough not to know better.

When I could just up and run out the door and jump in the car with my Uncle Troy, and go off and do it without feeling like Granny had caught me in the chicken shed with a National Geographic, and a goofy grin on my face. Back when it was every bit as respectable as using sassafras leaves when you found yourself without toilet paper, before some prissy-body invented baby wipes, and even polite folk could get away with calling orange-jelly Christmas candy “sheep-snot.”

It would be nice to do it in cut-off pants and yesterday’s dirty tee-shirt again, without the guilt that I’m supposed be in Orvis, or Filson, lookin’ pretty and wearin’ a blue bandana round my neck. Plying a three-weight and a Hendrickson, for brookies on a picturesque little Pennsylvania freestone, just below a red covered bridge, while all about the maples burn scarlet and gold. That way, at least, I’d be in character. Upholding the image people generally imagine of a man, painfully plain actually, who hides-out behind a by-line in an upscale outdoor magazine.

It’s just that those were good times, when I was about ten years old, and Uncle Troy got off from the post office at noon on Saturdays, about the time the whistle went off each day at the Asheboro Fire Station. And swung by to pick me up in his old black, turtle-backed Plymouth sedan, which would be loaded to the gills with fishing paraphernalia: rods and reels, tackle boxes, tubs and tins – Pfleuger Summit bait-casting reels, knuckle-busters, mainly, with black dacron line – stiff glass rods you could kill a snake with, lard buckets to sit on and a fresh baking of carp bait. All I had to do was holler “Bye” to Mama, jump in and go.

I’d be watching for him after midmorning, hoping he’d get loose early. Finally, I’d hear him coming. About three blocks away. I’d know it was him before he’d get even to Worth Street, cause the brakes on the old Plymouth complained of inattention, and Uncle Troy’d forget to give the tires air so they always ran low and squealed around the corners.

But he never forgot the important things, like a Zero bar and a Ginger Ale, that he’d picked up at Watkin’s Grocery on the way, a little brown sack with a spare oatmeal cookie or two, and a quart of chocolate milk to share later, if the carp were slow to bite and we found ourselves hungry. They’d be there on the front seat, when he swung the door open wide, and he’d say, “Haul in, Boy, and les us sally off a-fishin’.”

It was about nine miles through the country, to Grady King’s carp pond concession on Old Coleridge Road, just the other side of Purgatory Mountain, and we’d sip the Ginger Ales on the way. Cause Uncle Troy’s throat would be dry, from all the stamps he had to lick for folks on a Saturday morning back then. From all the palavering about turnip greens or the latest town gossip, cause it wasn’t polite to sell a man a stamp without asking how his garden grew.

The Plymouth would belch and lurch, but never give up, and the sun would be shining all around, shimmering off the silver bellies of the maple leaves, that the warm summer breeze had tickled to their backs. And I was so happy my heart was going to jump out of my throat.

“A fine day, Boy,” Uncle Troy’d declare. “The Lord got up on the good side of the bed today. Them carp gonna crawl right out on the bank and throw their fins up. Won’t even have to toss a line.” And he’d wink, and give me a big “who-haw,” as he struck a match on the metal steeling post of the Plymouth, to light up another cigarette. While he stuffed the one before, unfinished and smoldering, in a bulging ash tray.

I’d know now if I smelled like tobacco smoke, but back then it wasn’t much a matter, cause ever’body did. From Camels, or Phillip Morris, or Old Golds. Uncle Troy smoked Cools, with the penguin on the packs, green and ice-white. They’d kill him one day, but he didn’t know it yet, and if he had, it probably wouldn’t have mattered. But not before I was a man grown, and not afore we’d gone off and caught a lot more carp together, and he’d licked a blue passel of five-cent postage stamps.

I’d have to get out and pee again by the time we pulled up under the oaks in Grady King’s side yard, and dodged the gaggle of shepherds and hounds that milled and bawled around the bunch of cars gathered there already. Because I was so excited my eye teeth ached, the more when I saw again the rusty set of Chatillion scales that hung there, under the limb of a tree. Waiting to weigh in the biggest fish of the day, which won you five silver dollars, and a free fishing pass for the next weekend. All the way there, I’d imagine today it would be me that won, and what I’d do with a whole five dollars

Only a rooster and a rundown bait shack attend this abandoned carp pond, once a happy part of the southern sporting scene.

Mister Grady had about seven carp ponds on his place, and he didn’t open any one of them until one o’clock, and it was five-’til-one now, and everybody was gathered around fretting, waiting to pay and go on a-fishing. For two dollars, Mr. Grady would write you down for a pond; for three, you could pick your own. If he knew you pretty well, he might even sneak in a suggestion. Uncle Troy would take out his wallet and hand him three.

With that, Mister Grady would measure the stubble on his face with his spare palm, check to see who was watching, and lean in close. Cause he and Uncle Troy knew each other long before, from the Post Office.

”Take this boy over behind the curing barn,” he’d say, just loud enough for me to hear, “to Number Three. We jus’ hauled a fresh load of fish in there las’ week. They’s carp in there’ll go fifteen, maybe eighteen pounds.”

Mister Grady always enjoyed it when my eyes swelled. Course he’d tell us about the same thing every week, ‘cept it was always a different pond.

Nonetheless, when everybody rushed off, I was always afraid they’d beat us there, cause Uncle Troy was so slow, taking time to light all those Cools.

When they didn’t, we’d claim our usual place along the bank, under the leaning willow tree. There’d be five or six other clumps of people scattered around the pond, jabbering and staking out poles. You carried forked sticks for that, and nobody put out less than four or five.

“I bet nobody’s got bait good as ours,” I told Uncle Troy.

He gritted his teeth into an exaggerated grin and bobbed his head. We were always pretty smug about our bait. We’d stopped by Lettie Lutterlow’s, like always, along the way. Everybody knew she baked the best carp dough in the county. You had to order it two weeks ahead. I’d looked at the license plates in Mister Grady’s yard while he was doling out the ponds, and they were mostly from other places, like High Point or Gibsonville. Bet they didn’t have any.

Besides, Lettie and Uncle Troy were sweet on each other back in his courting days, before he married my Aunt Nettie – except the one time Grandpa took out the back seat of the Ford and hauled back a load of pigs. The afternoon before Uncle Troy and Lettie had a date. Uncle Troy had done his best, going to the drug store like he had and buying all that talcum powder to scatter round the back of the Ford. But there ain ‘t much way you can stop a pig from smelling like a pig, so the best that could happen smelled like a whore house with a busted sewer. Anyway, Lettie had finally forgiven that in later years, and would save us the finest and freshest batch of bait.

It’d come in big, heavy pads of dough done up in wax paper, and it smelled good enough to eat. Uncle Troy said Miz Lettie would rather show you the mole on her thigh than give away the recipe, but you could tell that at least, it had vanilla flavoring, licorice, a dash of butterscotch, and maybe, we thought, a sniffer of roadhouse brandy. And, of course, enough cotton to make it hang together on the hook.

You pinched off a wad and rolled it into a ball about the size of a banty egg and packed it onto the hook. Then you flung it out into the pond far as you could, and propped the rod on the stick, so you could take the slack out of the line with the reel. That way, when mister carp came along and started sucking on it – trying it out like they always did to see if they liked it – you could see the line rise and fall.

Some folks used a little bell on the line, between the rod and the water, or a small ball of dough, so you could hear or see it better – and get ready, afore he guIped it down for good and sailed off in a mad rush for the middle of the pond.

“Watch them rods, Boy,” Uncle Troy’d warn. “Don’t let nary an eye off of ’em.”

Cause if you did, a big ol’ five-dollar carp’d jerk one of them off-and-gone into the pond. Usually not for good, as somebody’d likely snag it out the next Saturday. But you were indisposed meantime.

Mostly, it was rare back on the running board of the Plymouth, chew on an oatmeal cookie, sip chocolate milk, and watch and wait for the suspense to thicken. Then snatch up the rod and cross his eyes when he made his getaway run.

When somebody fought one, it was a community event – Whooo-haw – everybody round the pond jumpin’ up and down, a-whooping and hollering encouragement. Carp were huge, when you finally rolled them out on the bank, compared to the twelve-ounce sunfish and six-inch horney-heads that were my normal creek fare. Five or six pounds, laying there in the grass, sucking air and grunting, golden and slick-headed, with scales the size of fingernails and the little fleshy whiskers on the pucker of their lips working like earthworms. And everybody came over to see.

Nobody ate them much. Said they were coarse and bony. But Granny could cook them, until the bones melted, and we’d have three or four – fried-up – if we were lucky, come dinner Sunday. And, Boy, they’s good.

“Well, Boy, I got to go off and lick another week of stamps,” Uncle Troy would tell me later that afternoon, reaching in his pocket and handing me two-bits. “That’ll keep you in Zero bars.” Cause you could buy five for a quarter. And I had to go back to school, be sad, and pine the way ’til next Saturday when we could go off again.

But I’m all grown-up and reputable now, and folks might say I ought not to do that anymore. I ‘spect I oughta just forget about a carp pond – nobody keeps ’em nowadays nohow – just be proper, knot a blue bandana round my neck, and make for Pennsylvania. The problem with unrespectable is that it’s too much fun.

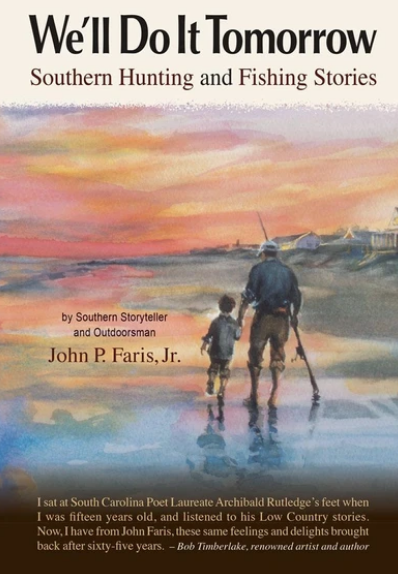

We’ll Do It Tomorrow: Southern Hunting and Fishing Stories by John P. Faris, Jr. Reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” Buy Now

We’ll Do It Tomorrow: Southern Hunting and Fishing Stories by John P. Faris, Jr. Reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” Buy Now