“I’m convinced that some dogs point things other than birds because they’re afraid of making a mistake.”

Here’s a tip: Should you ever be invited on a late-season grouse hunt with Terry Barker and me, the correct response is whatever variation of “No” you can hustle into play. For example, “I’d love to, but I promised my mother-in-law I’d give her a pedicure.” Or, “Geez, I’m overdue for a prostate workup, and my urologist just started offering weekend hours…”

What you have to understand is that these hunts are ritually brutal. Driving home after the most recent one, Terry groaned, “Oh, man, I hope I can make it to eight o’clock.”

What you have to understand is that these hunts are ritually brutal. Driving home after the most recent one, Terry groaned, “Oh, man, I hope I can make it to eight o’clock.”

“What’s at eight o’clock?”

“Bedtime.”

The other thing about these outings is that they’re typically (if not invariably) fruitless. Despite our minor local reputations as grouse hunters, any amount of snow on the ground pretty much shoots our supposed expertise to hell. We used to think we knew where grouse go when it snows, but then, there’s a lot we thought we knew before we became eligible for our AARP cards.

“Just off the top of my head, I recall my dogs pointing house cats, bedded-down calves, raccoons, porcupines, turtles and tortoises.”

Still, there are occasional compensations, small rewards that mitigate at least some of the pain and suffering. It’s not every day that you get a rock-solid point on a black bear, for instance.

Actually, as Terry describes the scenario — we’d split up to take opposite ends of the sprawling Woodtick Hollow cover — the identity of the pointed object is open to question. Summoned by Belle’s Guns beeper, he’d found the pretty tri-colored setter standing in the trail. Her posture was oddly recoiled, as if the scent was pushing her backward, and she seemed to be focused on a Christmas tree-sized balsam fir about forty feet away. Behind the balsam stood a dark, desk-sized boulder, a not uncommon sight in this neck of the woods.

Terry took a couple steps in that direction — and the rock morphed into, quote, “The biggest goddamn bear I’ve ever seen.” Displaying no particular concern, the lordly bruin shot a quizzical (or perhaps appraising) look at the dog and man, then casually ambled off. It hadn’t gotten very far, though, before it flushed a grouse.

While it’s true that Terry’s grip on reality can at times be tenuous, I honestly don’t think he made that up.

And no, he didn’t kill the grouse. (Now that would have been a tale for the ages.) His excuse, however, was unassailable, and quite possibly unique in the annals of the sport.

“I had no shot,” he shrugged. “The bear was in the way.”

Was Belle pointing the bear, the grouse, or both? Well, who knows, though it’s hard to believe that she didn’t smell the bear at such close quarters. Her atypical, backwards-leaning posture certainly seems to suggest that she knew something wasn’t kosher.

By the same token, it’s entirely possible she smelled the grouse, too. The canine olfactory system is so powerful, and so sensitive — drug- and bomb-detection dogs routinely react to concentrations of scent in the parts-per-billion range — that even a fetid blast of bear stink poses about as formidable an obstacle as wet tissue paper poses to a machete. Dogs point birds in the reeking wake of skunk encounters all the time; there’s even a credible story about a famous field trial setter from the 1960s, Tishomingo, pointing birds while in the process of proudly retrieving a skunk he’d just killed.

By the same token, it’s entirely possible she smelled the grouse, too. The canine olfactory system is so powerful, and so sensitive — drug- and bomb-detection dogs routinely react to concentrations of scent in the parts-per-billion range — that even a fetid blast of bear stink poses about as formidable an obstacle as wet tissue paper poses to a machete. Dogs point birds in the reeking wake of skunk encounters all the time; there’s even a credible story about a famous field trial setter from the 1960s, Tishomingo, pointing birds while in the process of proudly retrieving a skunk he’d just killed.

In other words, it’s damn near impossible to “mask” the scent of birds from a bird dog, just as it’s damn near impossible (as any number of guys doing hard time will attest) to mask the scent of drugs or other contraband from a dog trained to sniff out the stuff.

This begs the question of why, if their noses are so incredibly discerning, our dogs point so many things that aren’t birds? Spend enough time hunting in enough different places, and you’ll amass a long, interesting list of critters whose scent prompted your dogs to style up. Just off the top of my head, I recall my dogs pointing house cats, bedded-down calves, raccoons, porcupines, turtles and tortoises (the latter got to be a real nuisance in the Nebraska Sandhills), a variety of snakes (none venomous, thankfully), toads . . . You get the picture. If it has a pulse, they’ve pointed it.

One of the more vivid of these experiences occurred on a blazing afternoon in South Dakota. We were hunting chickens and sharptails on the Ft. Pierre National Grasslands, and when Emmylou posed decisively at the edge of a room-sized patch of big bluestem — the flame-hued sine qua non of the tallgrass prairie — I had no doubt that it was money in the bank. I strode in, my Fox 16 at the ready — but instead of the sky filling up with birds a young coyote broke cover. It didn’t get far, though, before Emmy nipped its heels and rolled it. The brush wolf came up bristling and snapping, and it was only with some difficulty that I was able to call off my dog, avert the possibility of bloodshed (on either side), and allow the coyote to scamper over the hill.

“I’m convinced that some dogs point things other than birds because they’re afraid of making a mistake.”

Then there was the time hunting quail on the Hapgood Ranch in Texas when Butch locked up next to a patch of coiled and ropy ground vines. It seemed an iffy place for birds — too thick, if you can imagine that — but Butch was resolute, so while Bubba Wood and Andy Cook guarded the perimeters, I waded in. I kicked around, kicked around some more, and was about to say “False alarm” when the piece of the vine patch directly in front of me levitated, shuddered violently and spat out a malign apparition that took me a bewildered moment or two to I.D. as a wild hog.

If you’ve never had the pleasure, trust me when I tell you that these beady-eyed porkers can really motor. Their razor-sharp tusks can rip a dog from stem-to-stern, too, although this pig vanished so quickly and comprehensively that our dogs just sort of looked around as if to say ‘What the hell was that?’ and continued about their business.

With exposure, experience and the proper reinforcement, most dogs learn to ignore “other” scents — including non-game birds such as meadowlarks (which can bedevil dogs on the prairies) and the various sparrows known generically as “stink birds” — and only point the real thing. Some dogs improve to a degree, while some seem perpetually befuddled, pointing anything and everything when by all rights they should know better. It’s as if they’re unable to make the super-fine olfactory distinctions that other dogs can, though I think issues of confidence — or, more precisely, its lack — factor in as well.

I’m convinced that some dogs point things other than birds because they’re afraid of making a mistake. This may not be an entirely man-made problem, particularly with “soft” dogs, but it’s one that excessive pressure contributes to. Rightly or wrongly, these dogs don’t trust their noses, so as a result they figure that they should always err on the side of caution. Sometimes you can tell by their body language — generally “loose,” lacking intensity and style, etc. — that they’re pointing “on spec,” but not always.

It can be frustrating to hunt over dogs like these, but take heart: There was a champion setter a few years back — an inductee into the Field Trial Hall of Fame, in fact — that throughout his career was an incorrigible pointer of rabbits. The thing is, you always have to give them the benefit of the doubt. They deserve at least that much.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2007 April/May issue of Sporting Classics.

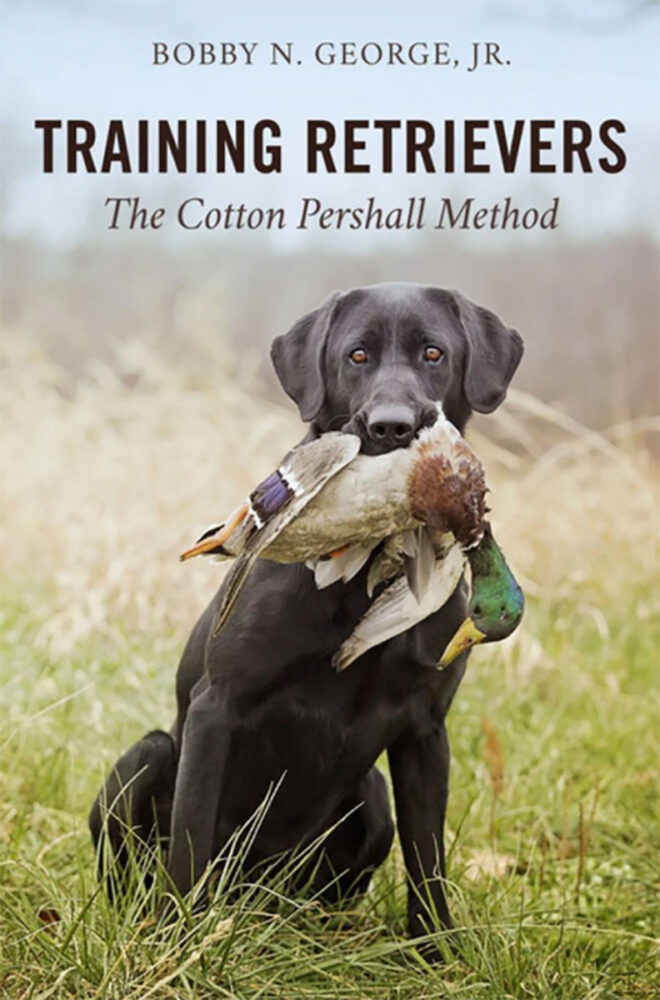

In the opinion of many, nobody was more influential or had a greater impact on retrievers—their training, handling, and breeding—than Cotton Pershall. This book was a command performance, because thousands of dog owners and trainers requested that Pershall’s methods be set down for generations to follow. Through the eyes and words of professional trainer Bobby N. George, Jr. that’s exactly what happened.

In the opinion of many, nobody was more influential or had a greater impact on retrievers—their training, handling, and breeding—than Cotton Pershall. This book was a command performance, because thousands of dog owners and trainers requested that Pershall’s methods be set down for generations to follow. Through the eyes and words of professional trainer Bobby N. George, Jr. that’s exactly what happened.

The book includes complete techniques and training guidelines for lining, marking, obedience training, play training, handling doubles and triples easily, land and water retrieving, the forced retrieve, techniques to make your dog a more effective waterfowl retriever, and starting puppies through finishing a dog—as well as fifty years of reminiscences about dogs, trainers, waterfowl hunts, and field trials. Buy Now