It was a hard life lesson this fisherman learned when forced to break his promise to fish another day, for tomorrows are never guaranteed.

The peaches, pinks, and purples of the sunset were mirrored in the wet sand of receding waves. It would be light enough this August evening on Pawleys Island, this three-mile slice of heaven along the South Carolina coast.

I was following the small footprints of my two young children, Ashley and John, and my seven-year-old nephew, William, in the warm seaside sand. William was the youngest of the three. He was my baby sister’s first child. He was a handsome young boy with thick brown hair and beautiful bright brown eyes. He was a four-foot bundle of energy, full of curiosity and a thousand questions. Because my sister lived in Atlanta, I did not get to be with William much except at the beach on shared family vacations. He loved to be outdoors and anything I was doing from checking crab traps, throwing a cast net, to fishing in the surf, William was always by my side. He would say, “Let me do it, Uncle Johnny, let me do it.”

The three cousins dashed ankle-deep into the dying edge of each wave, giggling and laughing at some made-up game they were playing. I was only half watching with my eyes. My mind was on tomorrow. I had been in charge of these three forever energized, mischievous rascals since early morning. Happy marriages offer trade-offs between busy moms and dads, and today was pay forward for the promise of a tomorrow all by myself surf fishing.

As the children danced twenty yards ahead, we worked our way toward the northern inlet of this barrier island. I was carrying my eleven-foot surf rod with a hammered finish, chrome Able spoon, clipped in the base of the first ferrule. When we reached the inlet, I planned to let the children play along in the fading light as I waded fifty yards or so further out on the spit of sand that separated the Atlantic Ocean from Pawleys Creek.

The day-trippers were long gone. Formations of brown pelicans were heading for North Island to roost, and the waves were pushing the falling tide into emerald haystacks.

I gave the standard parental instruction, “Y’all stay close, John, Ashley. Play right here for a few minutes while I go out and make a few casts. Don’t get into trouble, and we’ll make milk shakes when we get home. William, stay with John and Ashley, Okay?”

I began wading out. When I got knee-deep I freed the Able and turned the left-hand handle of the big Penn spinning reel. The right length for the one-ounce lure to load the rod was a foot from the reel tip. I flipped the bail and cast the silver missile sixty yards into the seaside surf.

I was not really fishing – if there is such a thing – only scouting for tomorrow.

After two more casts to the seaside with no encouragement, I tried in the creek’s direction thinking that since the tide had turned and the rip was forming in that direction, it might just be the ticket to hook a hungry bluefish.

As I began to make my first retrieve I felt a sharp tug on the hem of my faded rolled up khaki pants. Having seen sharks cross this shallow spit on previous trips, I instinctively jumped and turned and looked down into the face of William who was wet to the bone.

“William, what are you doing way out here?”

No sooner had I finished my sentence than a crossing wave knocked him a little off balance.

“You are soaking wet. Your mother is going to kill me,” I shouted above the crashing of the surf.

I continued retrieving the lure and saw him watching the revolving shiny spool. He pointed to it and begged, “Let me do it. Uncle Johnny, let me try.”

“No, no.” I told him. “The rod is much too big for a little guy.” I glanced back to the beach to be sure that my two were still out of the water. An upset sister is one thing. An angry wife is quite another. Seeing they were still somewhat in place on the shore, I said “William hold on to my pants pocket. I’ll just make a couple of casts, and we’ll head back to the house.”

I put the Able out into the middle of the increasingly more defined rip. Nothing.

“Please let me do it?” William begged, his eyes locked onto the big whirling spool.

“No. Let Uncle Johnny make just one more cast and we’ll go. Are you cold?”

The last attempt produced nothing more than disappointment. As I held William’s hand we slowly pushed our way through the falling chop over the bar. The water was late-summer warm, but the breeze made anything wet feel like forty degrees.

I gathered up my two children, still somewhat dry, and retraced our quarter-mile walk back to Snail’s Pace, our summer house. Lights in oceanfront cottages winked on in increasing numbers as dusk faded into darkness.

My two children raced ahead, milk shake promises pulling them home. Still holding William’s hand I could feel him trembling with the cold. I had nothing for him but “It won’t be long ‘til we’ll be there.”

Several times he begged “Me do it? Me do it, Uncle Johnny.” My final “No, William, we’ll do it tomorrow!” had a little too much bite. His hand slipped from mine, and I wished the words back.

Just to break the silence I said, “William your mother is going to skin both of us alive. Just look at us! You are soaked!” As we climbed the last of the steep steps over the dunes I said, “Go get some dry things on, and I’ll get the milk shakes ready. You want vanilla or chocolate?”

“Vanilla,” was the expected answer. His grandfather, my dad, loved vanilla ice cream, and William copied everything his beloved Dee Dee did.

As I slipped into the kitchen and fired up the forty-year-old Hamilton Beach blender, I could hear my sister all the way from the other end of the small house say “William, where in the world have you been? You are soaked! Come get in a hot shower right now!”

I was glad to be in another part of the house, away from her. I knew she would calm down a little while doing the shower thing.

I made three milk shakes, two chocolate and one vanilla. To soothe my conscience, the vanilla was extra large. I was determined to take William out in front of the house tomorrow, make a few casts, and let him reel the line in. I would make it all right.

Morning dawned with promise. Payback time. My day off. I fished the south end hard, then moved to the north end for a couple more hours with no better luck. By noon a dark front moved on a west wind. I made it to the house as the sand began to blow down the beach in lateral lines that stung my knees.

I was showering off some of the salt and sand under the house in the outside shower when my wife, Claudia, peeked over the wooden shower door and said, “Everyone thinks the rain has set in, and since this is the last day, we all think we should pack up and leave early.”

It was an idea hard to argue against. The weather was growing worse with every passing minute. I packed the Oldsmobile station wagon in pouring rain. It made no difference. In ninety- five degree heat by the time I would have completed the loading of suitcases, beach toys and fishing gear, I would have been soaking wet, no matter.

The next time the thought of William crossed my mind was late that night back at home in Spartanburg when I unpacked, washed and cleaned the rod and reel. We would probably go back to Pawleys Labor Day for a final trip. I would make teaching William a priority then.

That trip never happened.

Instead a call came from my dad. Mom and Dad were immediately heading to Grady Memorial Hospital in downtown Atlanta. A car had hit William as he and his dad were leaving a Braves baseball game. William had massive head injuries and many broken bones. A nine-day vigil at the hospital by the family and friends followed.

I realized the extent of his injuries when on the second day the nurses asked my sister for a picture of William. They wanted to see what he looked like. I never went into the room where William lay. I did not have the courage.

On day ten William went to be with the Lord.

A week after the funeral my neighbor, a doctor, assured me that William’s death was a blessing. My head told me so, but my heart would not accept it. A few days later, I sat beside my sister in her living room. She stared into nothingness. In a drugged monotone she mumbled, “We wanted to donate William’s organs to maybe help some other child. When I asked the doctor what they were able to use, he looked at me and nervously said, ‘Why Harriett, William was a healthy seven-year-old. There was nothing we could not use, eyes, skin, all the organs. We were able to use it all.’”

Harriett said she had turned to the doctor and said, “Eight.” The doctor said, “I’m sorry, I don’t understand.”

Harriett said “William was eight, not seven. He died on his birthday.”

After two weeks of on-and-off private weeping, I did not think I could cry any more, but I was wrong.

Since that day I have been blessed to fish in many places around the world. I have caught and released some big fish. I have surf fished up and down the east coast many, many times. I have also returned to our seaside cottage on Pawleys Island several times a year for over twenty-four years, but I never pick up my surf rod and wade into the waves that I don’t remind myself of my promise to William.

Until this day I have never told this story to my sister and the pledge I made to never, ever again, say to a child, “No, no. We’ll do it tomorrow.”

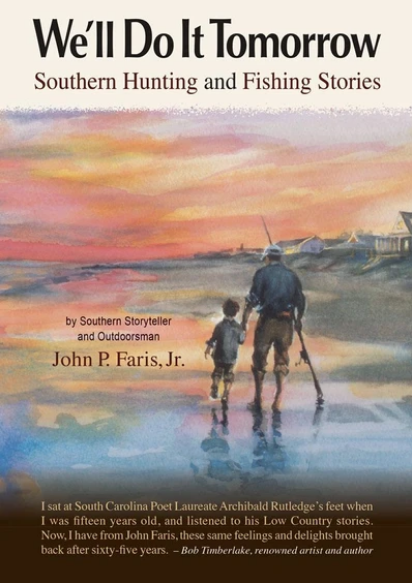

We’ll Do It Tomorrow by John P. Faris, Jr. is reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” Shop Now

We’ll Do It Tomorrow by John P. Faris, Jr. is reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” Shop Now