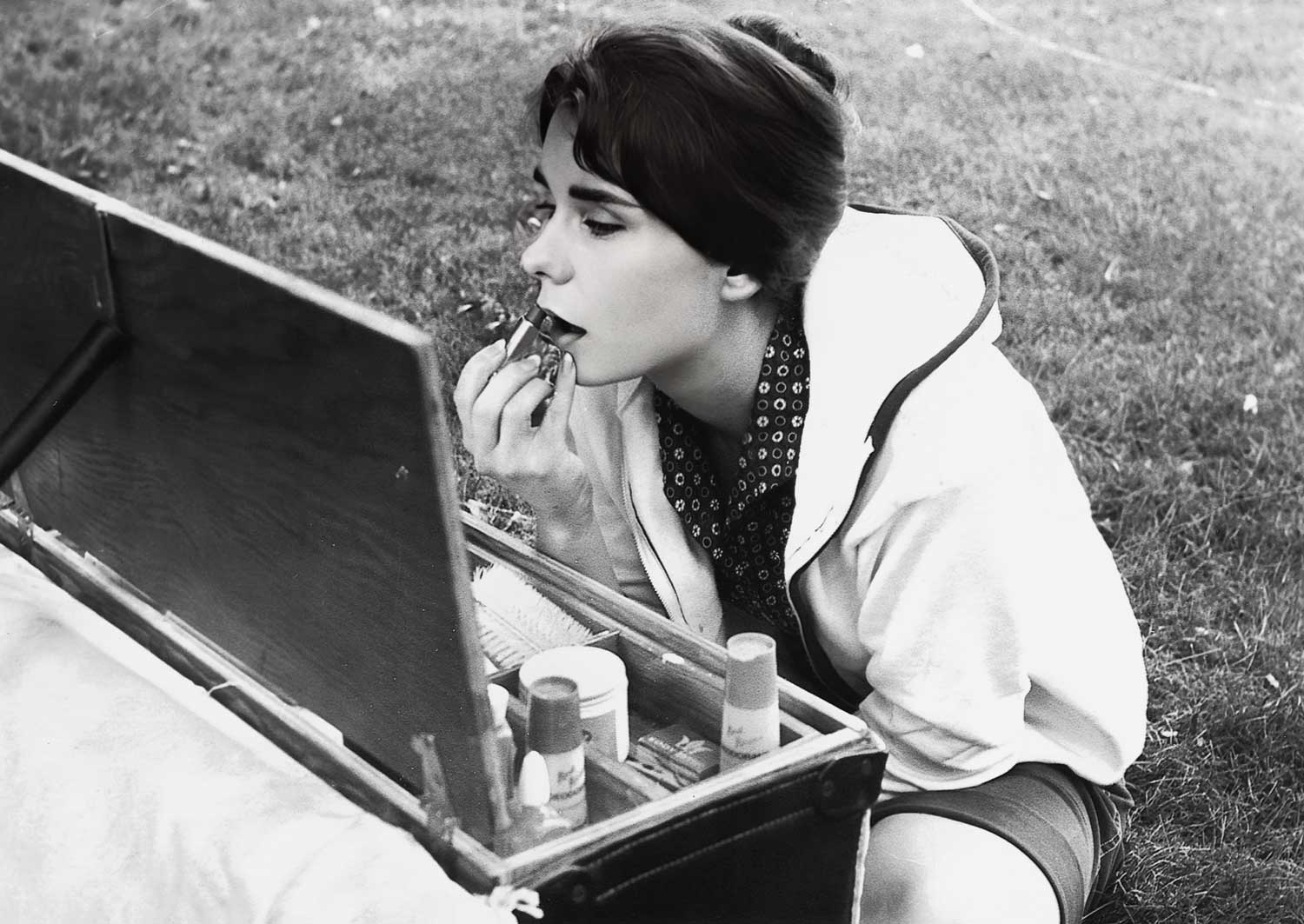

The Little Dove was pouting, and when she pouts she is such a virtuoso that connoisseurs come from miles around to watch and to admire. Hers is a ladylike pout, an I-married-a-madman-but-I’ll bravely-put-up-with-it pout. It would break your heart to watch her.

She had gone into her act when we pulled up in front of the group of three adobe houses down there in Sonora, and I had stopped the car in front of the most dilapidated and had said, “Well, here we are. Here’s home!”

She could look through the doorless entrance and see evidence that cows had used the hut as a refuge during bad weather. She could see the litter of thorny cholla balls, cow dung, sticks and trash that was a pack rat’s nest in one corner. Where we sat in the noonday Mexican sun at over 4,000 feet elevation, the thin, invigorating, high-altitude air was pleasantly warm. The frost of winter nights still hung in the miserable adobe hut, however, and when a gentle breeze stirred, we would feel and smell the chill, dank, musty effluvium of the old house . . . bats and manure and pack rats and the faint ghosts of gone and forgotten Mexican meals . . .

The three houses that formed the village were about a 100 miles south of the American border in Sonora and about 25 miles from the good highway that leads from Nogales, Arizona, south to Hermosillo, Sonora. As you shall see, it was and probably still is one of the greatest whitetail countries on earth. I had found the spot the previous year by the simple expedient of turning off the highway and following a miserable excuse for a road that led toward blue, oak-clad mountains to the east. Now I was sharing my find with my family.

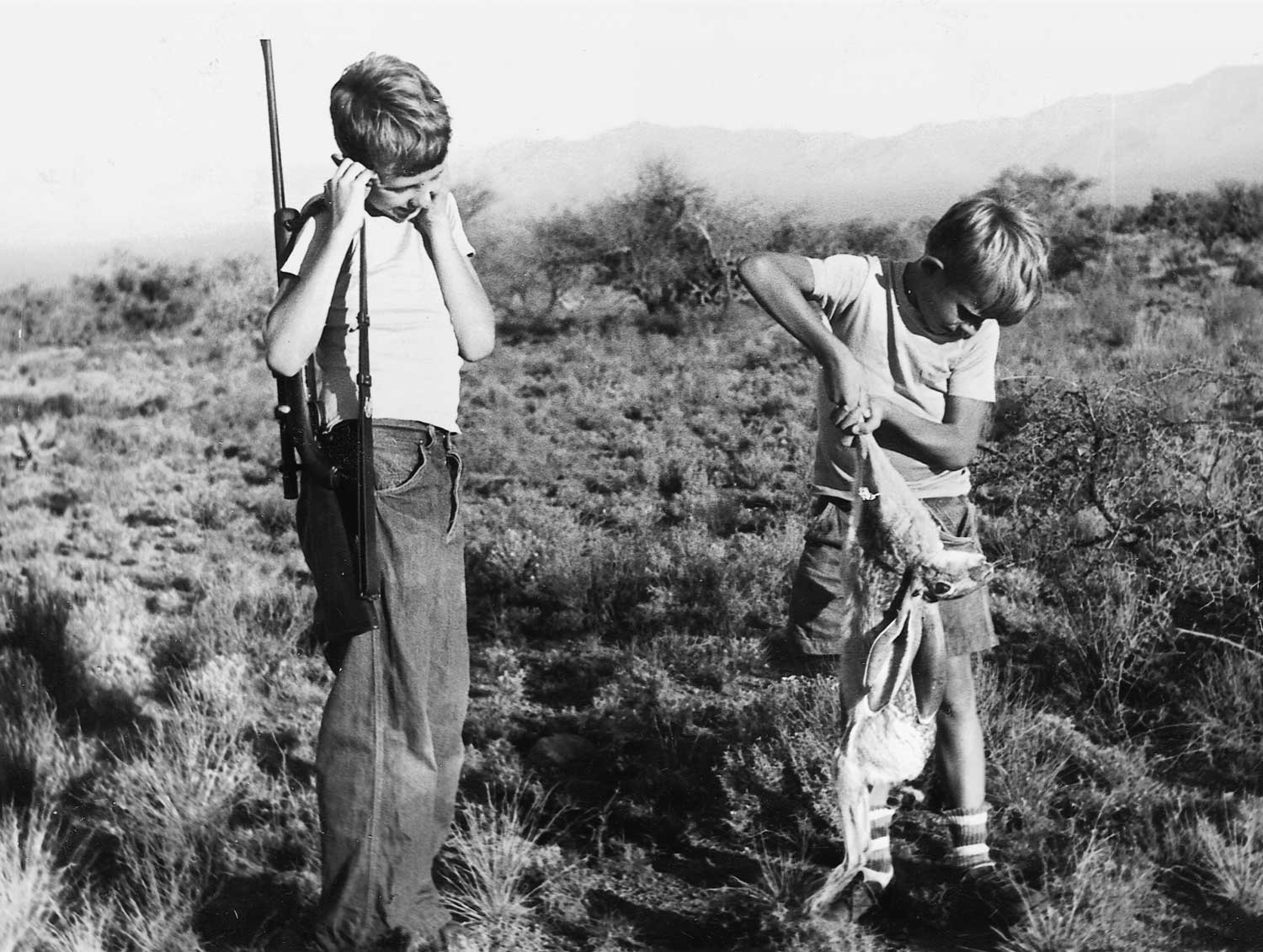

The two boys, Brad and Jerry, then little fellows, were sitting on a pile of bedrolls, food and gear in the back of the car. They looked around with wide-eyed interest.

“Is this where we are going to stay?” Brad asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“It stinks, Daddy,” he told me.

“Mamma’s mad,” said Jerry.

“Come on, boys, and help me unload the car and make camp,” I ordered.

With the broom I had brought along, I swept out the litter in the hut. The “stove” was a raised platform of adobe (dry mud bricks) under a hole in the roof, which served as a chimney. Some of the numerous scrubby chickens that ran around the place dodging skunks, coyotes, foxes and hawks and somehow making a precarious living from bugs and weed seeds had been roosting on the stove, and it was littered with their feathers and their droppings.

Gradually the boys and I made order in the hut. We put up our four folding cots and laid the bedrolls on them, set up a folding table and stools, stacked the food boxes so they were accessible, built a fire on the estufa. Slowly the place warmed up.

Finally, I opened a couple of split pints of Hermosillo beer and called my wife: “Come here, my proud beauty, and I’ll buy you a beer!”

I heard the car door slam and presently she came in looking slightly sheepish. She glanced around and grinned.

“I’ve been acting like a heel,” she said, “and I’m sorry. You and the boys have been sweet. I was tired and this place was so horrible, I just couldn’t face it!”

Some Mexican children had been eyeing the activity in our hut from a distance and now they gathered up enough courage to peer in the door. There were three of them – a little girl about 6, a boy of 8 or 9, and another of 12 or so. The two youngest children wore only very dirty blue shirts, and the 12-year-old was clad in what was left of the upper third of what had once been a pair of cotton pants, but which now was little more than a breechclout.

“What are you called?” I said to the children.

The little ones squirmed in horrible embarrassment but the 12-year-old said, “I am called Jose.”

“Who is your papa?”

“My papa is Manuel Parades, and I know who you are. You are one of the three gringo hunters.”

“Where is your papa?”

“He is up the little river to wash for gold.”

Eleanor dug around in a grub box and presently came up with a box of chocolate candy someone had given us for Christmas. She extended it to the children.

“Like candy?” she asked.

With a little coaxing the children each took a piece, sampled cautiously, gobbled enthusiastically, then took another. For a few minutes our boys and the Mexican children stared at each other as if they were from another planet, then they all went out to play.

As the babble of their voices faded away, Eleanor got up off her stool, walked to the corner where her .257 was leaning in its saddle scabbard. She picked it up, withdrew the bolt and looked through the bore, blew some dust from the scope lenses, buckled on a little leather cartridge box. Then she turned to me. “I want to go hunting.”

“It’s a bit late, old girl, but we’ll take a turn and see what we can see,” I said.

It was only a little after three when we started out, but the December sun was already headed for the horizon and a faint chill in the thin clean air was replacing the warmth of midday. To the north the mountain range rose like a wall. The lower slopes were thinly clad in picturesque and thorny desert growth – saguaro (giant cactus), palo verde, cholla, different varieties of long-armed feathery ocotillo. High up at the heads of the canyons the thorny stuff was replaced by the evergreen oaks the Mexicans call encinos. Still higher on the lofty peaks and ridges grew great yellow pines with red boles and whispering open crowns.

My plan was to hunt south along the foot of the big mountain a mile and a half or so to a cluster of brushy foothills where the year before I had always seen deer. We hadn’t gone a quarter of a mile when we ran a young doe out of the brush and up on the mountainside. Deer sign was everywhere. Now and then we’d hear them move off in the brush, but for a time we saw no more.

When we got to the little foothills, I told the gal to sit down on the hillside overlooking a saddle between the two highest knobs. It was a natural deer pass, and I thought I could run some deer through it by working around the hills. I sat down in the sun and waited for her to climb to the saddle.

Once, as she toiled up the slope, I saw the gray form of a deer slipping through the brush to her right. Finally, I saw her come out on the saddle and walk up the hill where she sat down with her rifle over her knees and lit a cigarette. Then I took to the brush.

I hadn’t gone 50 yards when I heard a deer move in front of me. Then I heard another. Droppings were everywhere and so were fresh tracks. I was halfway around the hill and was heading back toward the saddle when I heard two shots. When I got to the pass, Eleanor was standing over two bucks, one a fine big four-pointer, the other a spike.

“Good going,” I said. “How many did you see?”

“Gobs,” she told me. “First I saw a whole bunch of does and little cute fawns. I was watching them when a great big buck sneaked by before I could get a shot at him. Then these two came over!”

I laid the old .30/06 up against a boulder, took out my pocketknife and removed the insides of the two bucks. Then I put each across a big boulder, propped open the belly cavities with sticks so the frosty night air would chill them out.

“Well,” I said finally, “let’s wobble back to our little gray home in the West. Night is coming on, my pretty, and if we don’t hustle we might get et up by coyotes or mountain lions or something.”

“You take the little buck,” Eleanor said, “and I’ll take both rifles.”

“They’ll keep. We’ll come back with Manuel in the morning with horses.”

“If you don’t carry that buck in, I’ll do it myself. Didn’t you notice those kids? They were starving! Did you see those big bellies, those skinny legs, the hollow eyes? I’ll bet they haven’t had any decent food in months.”

In some ways I am a fairly observant character. In others I am not. Since the gal had mentioned it, I remembered that those kids had looked pretty gaunt and wide-eyed. It occurred to me that the people along the rillito might be having a tough time. They had a few rocky little milpas back in the canyon, where they diverted water from the creek to raise corn and a little chile.

When they were feeling industrious, they panned gold in the sands, but it was hard, poorly paid work, and if they got a few flecks to the pan, it was about all they could expect. In addition, the storekeepers back in the towns on the highway generally gave them about half what their gold was worth. They had got most of their cash income by acting as cowboys for a rancher who had run cattle in the area, but there had been a drought in that country and for a couple of years now there had been no cattle in there. That meant no wages for cartridges, for sugar, for coffee, for lard . . .

That little spike buck was deliciously fat, though I seriously doubt if he dressed out more than 60 pounds, maybe not over 50. But as anyone who has ever lugged one in over his shoulder knows, a dead deer is pound for pound probably the heaviest burden in the world.

It was almost dark when we got back to our hut. The five kids were playing in front of the shack. Jose was teaching Bradford how to handle a lariat by roping the little girl. All were smeared ear to ear with chocolate and the box of candy was a shambles.

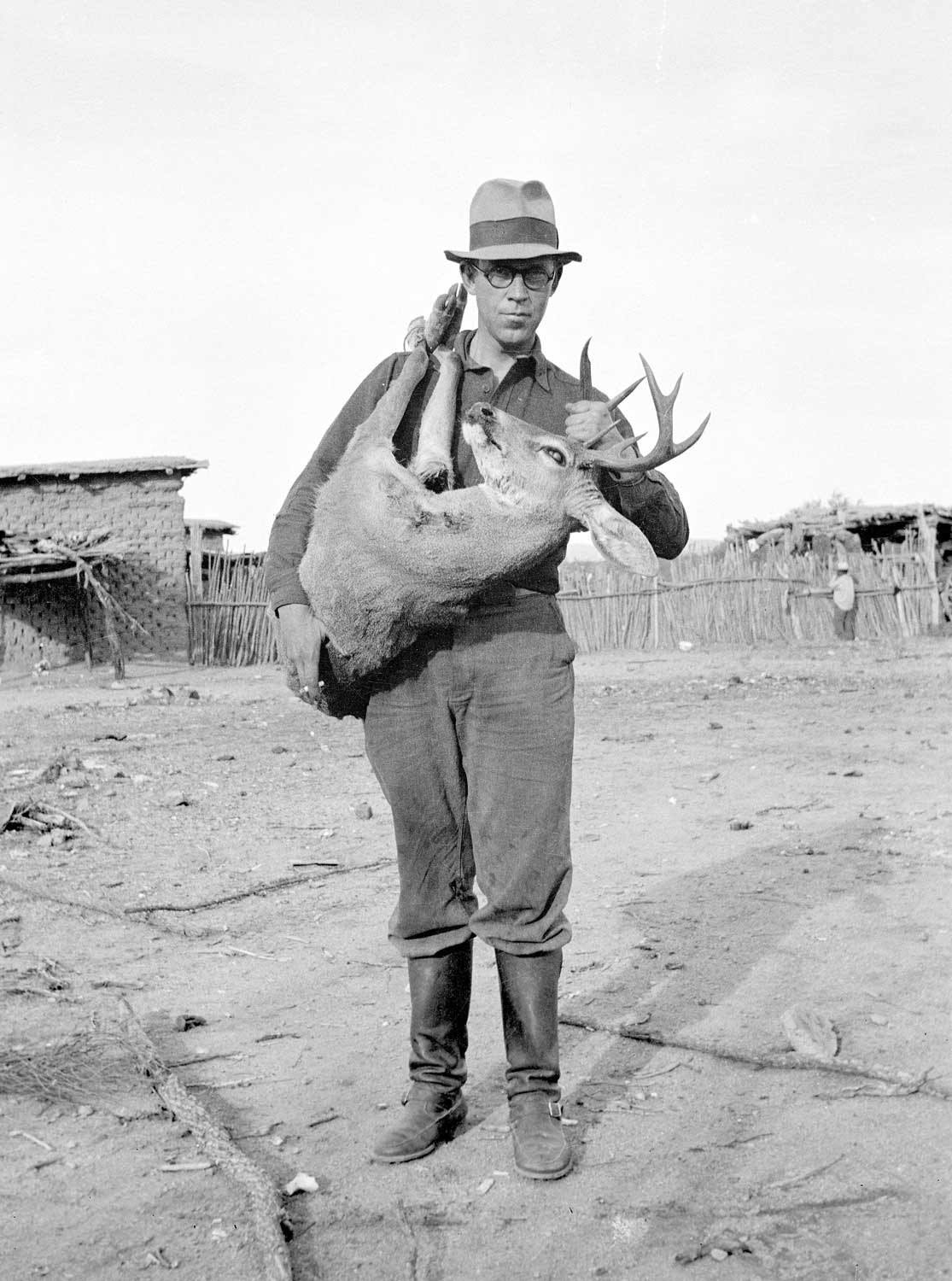

Manuel, the father of the three, had returned from his placer mining. He came up to greet me with a smile and the characteristic limp handshake of the country Mexican. Manuel was a tough and skinny little hombre, a fine horseman and a good hunter, but right then he was pale under his tan. When he helped me hang the little buck in the enormous mesquite tree that grew in front of the houses, even lifting his share of that diminutive buck seemed an effort.

“How are things going, Manuel?” I asked.

“So, so,” he said.

“I’ll take the backstraps of this little buck for breakfast. You take the rest.”

“Thanks,” he said, his face lighting up.

“Have you had much meat of the deer to eat?” I asked.

“I have no money to buy cartridges!”

“Do you have coffee?”

“We have no money to buy coffee.”

The staples of life to the poor Mexican are frijoles (beans), coffee, a coarse and unrefined but delicious sugar called pinoche, meat lard and corn. With no work, no cartridges, little gold dust, the families down there on the creek at the edge of the mountains had been living for months, I found out, on field corn boiled in water with a little salt. Now and then they had devoured one of the scrubby little chickens that had escaped the predators, and occasionally they fed the children an egg.

“But we are very poor,” he concluded. “Many times the children cry because their bellies hurt. This meat will taste good!” Then his face clouded. “Soon comes the New year. Now we have meat, but we do not have fat. We cannot make tamales and enchiladas. Alas, we have no coffee. We do not even have an onion! We cannot have a feast!”

Eleanor, whose knowledge of Spanish is far from profound, had nevertheless been catching a word now and then as Manuel and I skinned the buck. When I came in with the backstraps, the glowing gasoline lantern had made the hut bright and cheerful and good smells came from pots on the fire built on the mud platform that was our stove.

“Things are pretty tough with them, aren’t they!” she asked.

“They have been living on dried corn boiled in water. They don’t even have any fat. Nor do they have coffee. I can’t imagine a Mexican house without coffee or tortillas!”

She started rummaging through our supplies.

“We can spare some sugar,” she said, taking a sack out, “and we can give them a pound of coffee, some lard and some canned fruit. I’ll give them a couple of loaves of this bread we brought from home. I’ll make biscuits in the Dutch oven. I can spare some flour, too. With the venison they can have a feed tonight.”

“What hurts Manuel,” I told her, “is that the New Year is coming up in a few days. They haven’t got the makings of tamales and enchiladas. You know how Mexicans are about holidays. Tamales are to them what the New Year’s goose is to us!”

“We’ll fix that!” she said.

That night there was feasting and merrymaking in the little community. Now that the housewives had lard, they ground up corn into coarse meal in the same sort of stone metates their Indian ancestors had used a thousand years before. Then with salt, lard and water they made the corn cakes called tortillas and cooked them on a piece of sheet iron over an open fire. The coffeepot bubbled and from an old lard can on the fire rose the delicious odor of venison and chile bubbling along with an onion Eleanor had furnished. But as the coffee and the tortillas were finished, most could not wait for the stew. Instead, they cut strips of meat from the little buck, toasted them over oak and mesquite coals, and devoured them with a little salt. The meat and coffee made them a little giddy, and later, I fear, someone broke out a jug of home-distilled sotol, a drink that tastes, to me anyway, like rubbing alcohol mixed with high-test gasoline.

Before I turned in, I sat around the fire for a time and talked to the men about the coming hunt. Manuel promised to be out at the crack of dawn to catch the horses, so as he put it, we “could hunt while the frost still lay white on the grass and the big bucks stood stiff and shivering on the ridges.”

I gave Manuel and his brother Ramon 75 pesos in advance for horse and guide hire, in addition to 25 pesos for treinta-treinta (.30/30) cartridges. In those days, that was about $20, but it would buy some cartridges and a lot of simple food.

While Manuel hunted with Eleanor and me, Ramon was to ride into town by a shortcut with a packhorse and return with frijoles, lard, sugar, coffee, onions. Before I left the fire, the kids had gone to bed in a clammy, unheated room in their parents’ house. I peeked in to see how they were making out. The three huddled together on a cowhide that lay hair side up on the dirt floor and over them was a thin cotton blanket!

When I joined my family in our own hut, I was told the burro had tried to move in on them for the night and they had been forced to throw out a scrubby little rooster they had found perched quietly on the stove. As we dozed off to sleep, the place next door was still jumping.

The next morning I was already awake when the little rooster Eleanor had given the bum’s rush the night before greeted the dawn from the big mesquite. I got up, started the fire on the adobe platform, got a bucket of water from the rillito, made coffee, fried bacon and backstraps and browned toast. Presently we were all dressed and organized. But no horses arrived and no sound did we hear from next door.

Presently, though, I heard an axe whacking at the woodpile and went to see Manuel’s wife gathering wood for the fire.

“Where’s Manuel?” I asked.

“Sick at the stomach,” she told me, shaking her head.

Just then Ramon’s esposa emerged with a bucket to go to the creek. By a curious coincidence Ramon was also a bit under the weather with an ailing stomach. It was, they told me, a case of too much fresh meat. The sotol? Of course the sotol could have had nothing to do with it, as it is a fact known all over Mexico that there is nothing like a slug of sotol to settle the stomach . . .

I didn’t want to let the big buck Eleanor had shot the night before get warm from the sun, so I caught the indignant burro that tried to move in the night before, managed to put an oversize sawbuck pack saddle on him, and while he moaned and protested like a man having his leg cut off, I led him into the hills, loaded the buck on him, and managed to get him back.

By that time, so slow had we progressed, it was almost noon.

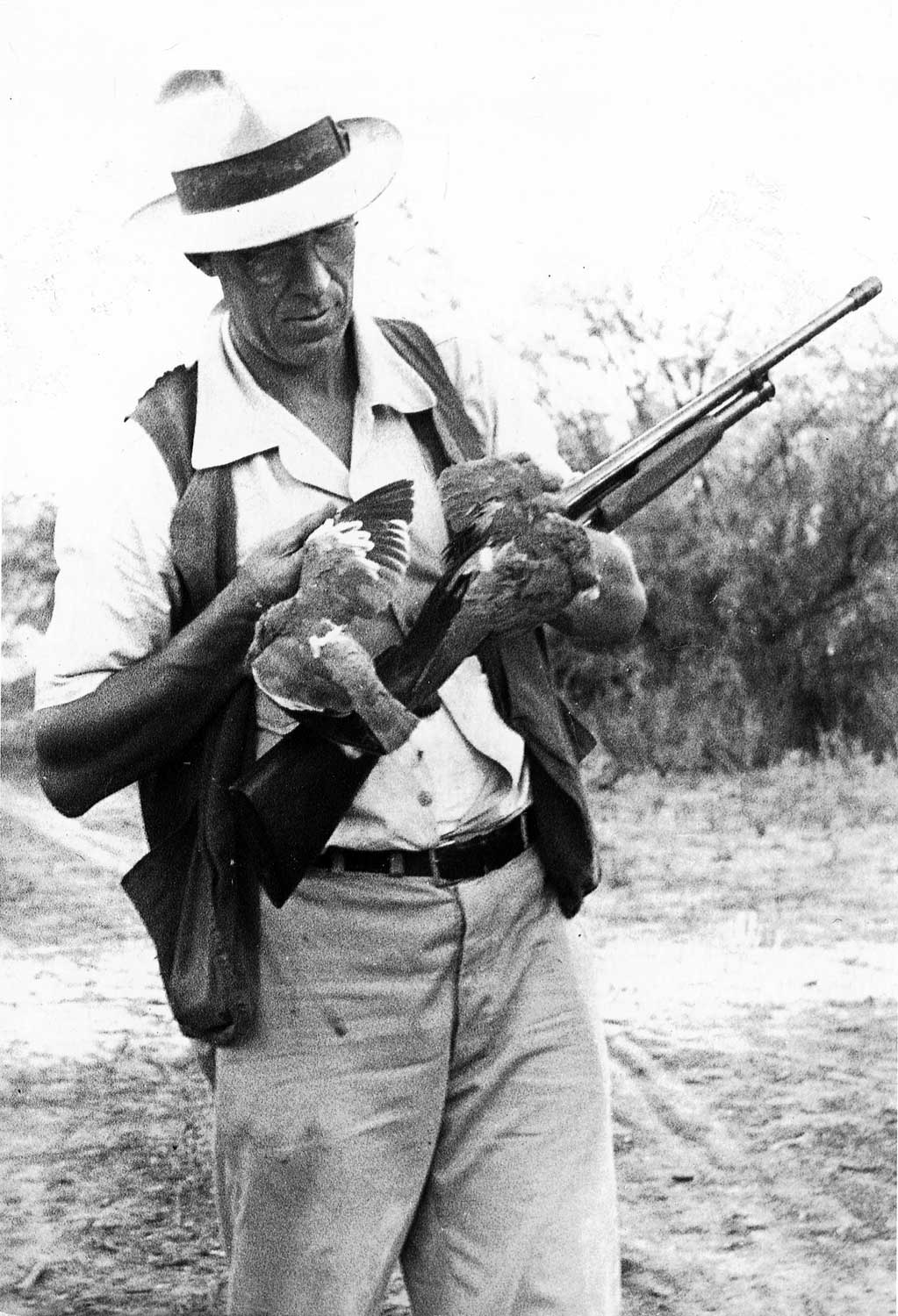

Eleanor told me that not long after I left, Ramon had ridden off to town to buy .30/30 cartridges and grub, and that Manuel had gone into the hills to find our horses. In the meantime, Eleanor had taken her shotgun and had hiked with the boys back into one of the milpas in the canyon where she shot eight of the gorgeous tropical Benson quail, birds of blue, gray and orange with long orange topknots. So far as I know that little milpa is the very northern limit of the range of this, “the elegant quail,” as it is sometimes called.

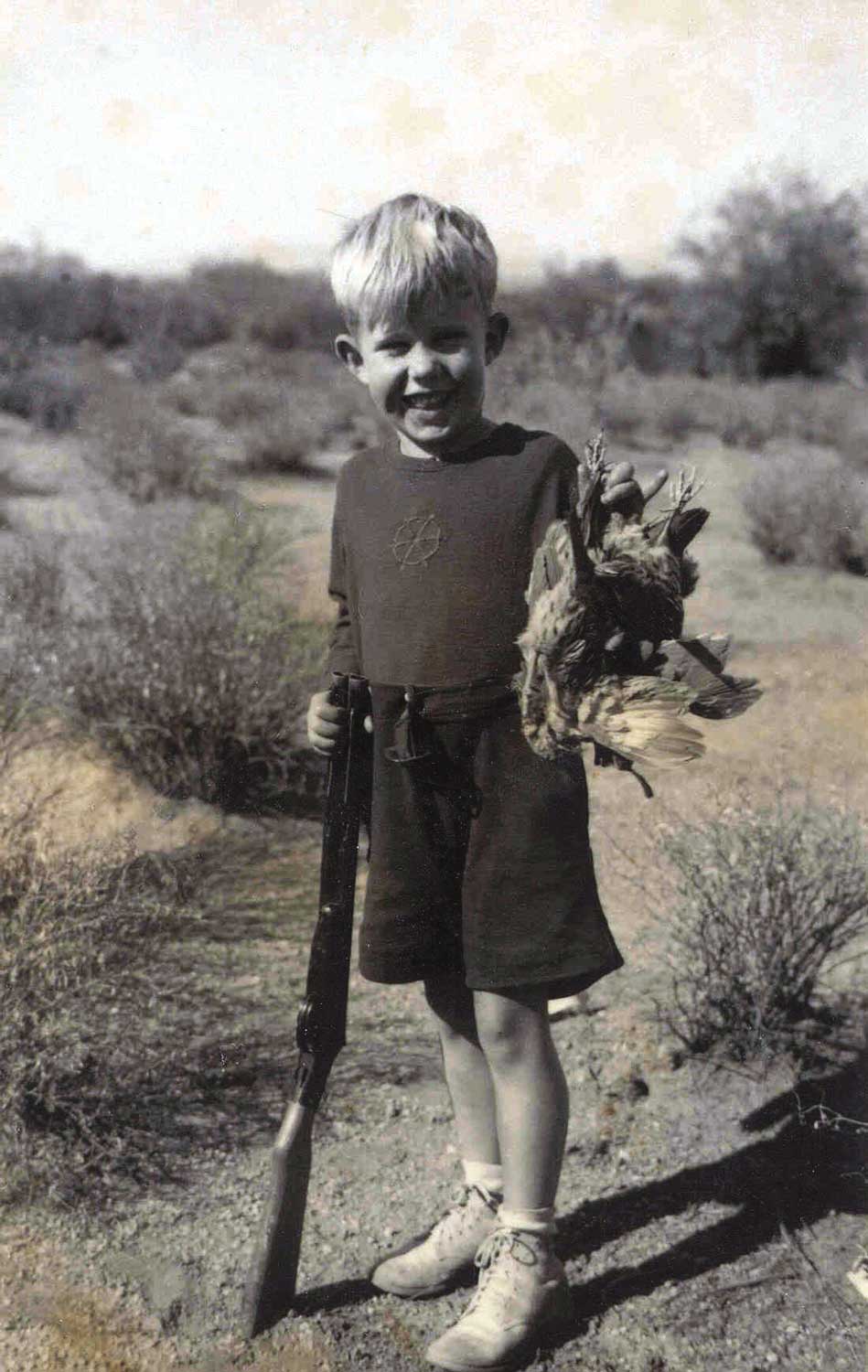

Brad O’Connor at age 5, armed with his toy double gun, retrieves a brace of Gambel’s quail.

We lived a wonderful, lazy life those ten days we stayed in the village. If we wanted to hunt quail, we had our choice of the lovely Benson quail up there in the milpas where the little river came out of the mountains through a deep canyon or the Gambel’s quail that lived lower down along the arroyos. And that isn’t all!

One day when we hunted high in the mountains in a region where cattle seldom ranged and the rich gramma grass was belly high to a horse, Manuel saw some Mearns quail scurrying through the grass. He was carrying the shotgun on his horse for us that day, so Eleanor piled off and went on a quail hunt there at 7,000 feet elevation on the grassy slope of a big peak.

The Mearns quail is generally called the fool quail. He is a simple and trusting soul who depends on squatting in the grass for protection against hawks. Often, he can be killed with sticks or even picked up in the hand – hence the name. He is, though, one of the most delicious birds in North America. For a quail, he has a very large breast, tender, delicious, faintly flavored with all manner of wild and wonderful things.

And every afternoon not long before sundown hundreds of mourning doves came hurtling down right across our adobe hut from the mountains. They fed up there on weed and grass seeds during the day and then as the afternoon shadows lengthened, they came whistling down to water in the creek and roost in the cottonwoods that grew along its banks. When the flight was on and we wanted a dove stew, all we had to do was step out of our hut and go into action.

Deer were everywhere – high on the grassy ridges, in the oak thickets of the draws up in the hills, clear down in the cactus and catclaw. Sometimes we’d ride far back into the hills, but often we’d simply walk out from the house.

Once, Eleanor went on an expedition with the two boys over toward the hills where she had got the bucks the first day. Presently, I heard a shot and a little later Brad came running back to tell me that mamma had shot a buck and for me to come and “take its stomach out and throw it away.”

I tried to space the shooting of my own limit of three bucks in order to meet the food situation, and I must have seen 50 or 60 mature bucks I never fired a shot at. A couple of times I rode out with Manuel, let him carry and use my rifle to get some meat. I have a suspicion that Manuel and Ramon traded some deer they had killed with the .30/30 ammunition I had bought them for some more food and some clothes, because Jose showed up with a shirt and a pair of pants and the little girl was bouncing around in a calico dress.

This was the day after three nice fat bucks disappeared from the big mesquite tree in front of the house.

At any rate, the two families were eating well and were thriving. It was wonderful to see how quickly the gaunt faces filled out and color came into those pale cheeks.

The day before the New Year there was a great hustle and bustle in the houses along the creek as the women made tamales for the New Year feast. They ground up corn, mixed it into a white paste with lard, flavored it with salt. They boiled quantities of venison, then diced it up, flavored it with a rich chile sauce. They washed, sorted and trimmed corn husks. Then the women spread the corn mixture on the husks, put on a dab of the meat and chile mixture and folded it all up into a tamale. That night we could see clouds of mist rising from a big lard tin as they steamed them.

On New Year’s Eve, it pains me to admit, the O’Connors were all busy pounding their ears as the old ear died and a new one came into being. The boys had insisted that they were going to stay up until after midnight, so after we had eaten, we tuned in the portable radio on an American station. They had played hard during the day, though, and by nine o’clock they decided it would be nicer to listen from their beds. In a few minutes they were asleep.

Earlier that day Ramon had brought us over a bottle of sotol from a still he had back in the hills. Valiantly we tried to drink some of it mixed with grapefruit juice, but it didn’t put us into any holiday spirit and by ten o’clock we were in our sleeping bags.

The next morning the sun was well up and the Mexican women were bustling before I awakened. For once my friend the little rooster had forgotten to greet the dawn. After breakfast Eleanor decided that she’d take the boys and go quail hunting down the creek where there were several coveys of Gambel’s. With Ramon, I rode down to the southeast to see if I couldn’t wind up my limit of three bucks, since about all the meat that was left had gone into tamales.

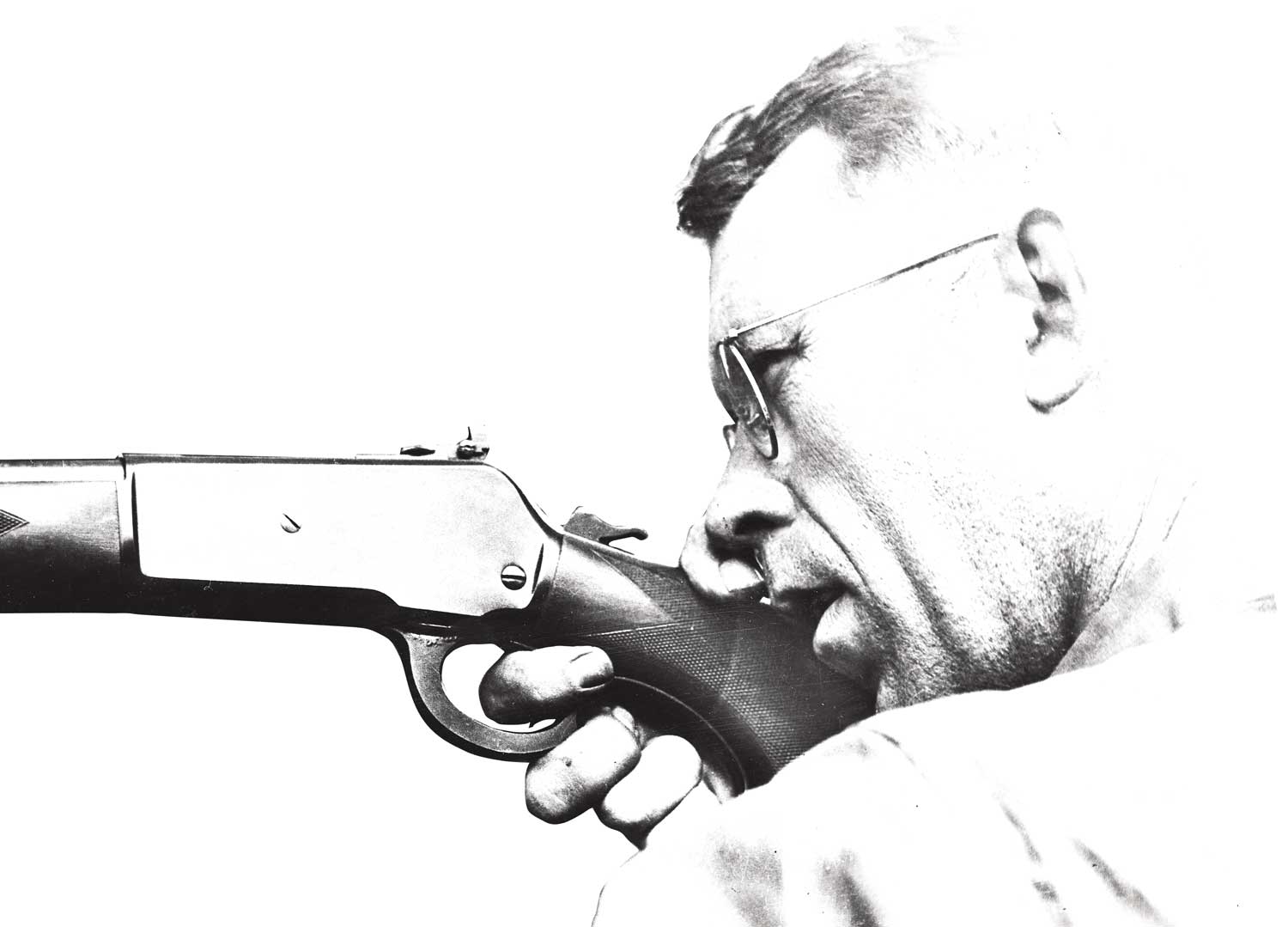

In a little chain of round, cactus-covered hills, I tied my horse, took my old .30/06 out of the saddle scabbard, and waited on a hillside while Ramon made a wide circle to the mouth of the canyon below me and then rode up it. Long before I could see or hear him, deer started to sneak out the canyon and disappear across the saddle into the head of the next canyon.

First came a dainty little blue-gray doe with twin fawns. After her, sneaking along head low came a gaunt old buck. He had a good head, but I knew he was too thin to be good meat so I let him pass. Then came a whole flurry of does, fawns and young bucks.

By now I could hear the sharp click of the feet of Ramon’s horse on rocks, and I had about decided that we’d have to try another canyon. Then I saw him – a nice, four-pointer in the prime of life, so fat that his grizzled-gray back looked as wide and meaty as that of a feed-lot polled Angus steer.

It really wasn’t much of a shot. I simply waited for him to go past an opening in the brush and cactus about 125 yards away. Then I led him possibly a foot and squeezed the trigger. I doubt if he even twitched.

Ramon and I brought the deer back and hung him in the tree about the time Eleanor had dinner ready. All in all it was quite a feast – broiled venison chops, mashed potatoes, tomatoes, dove-and-quail stew. She had even made an apple pie in the Dutch oven.

We were about to tear into this provender when a delegation of our neighbors showed up. They carried a couple of dozen tamales steaming in their husks and a dozen delicious flat enchiladas, which are corn cakes fried brown and crisp in deep fat, then dunked in chile sauce, and sprinkled with white cheese, chopped up pepper and onion. We were up to our ears in food.

Beaming, the delegation stood by while we sampled the dishes. I devoured a couple of the enchiladas, washed them down with frosty beer. Then I opened up a tamale and took a bite. To my amazement the meat was white.

“This is not venison!” I said to Manuel. “What is it?”

He howled with laughter. “That,” he told me, “is the rooster, the noisy one that tried to sleep on the estufa, the one that awoke you in the dawn with his shrill cries from the trees!”

I took another bite. That chicken tamale was wonderful. Then I turned to Manuel. “What do you have in the others – the burro?”

And that crack was quoted all through the area. It established me not only as the husband of La Cazadora (the lady hunter), but as a wit and quite a guy in my own right!

Note: Originally published in Outdoor Life, “We Shot the Tamales” relives one of several hunting trips in Mexico made by the O’Connors in the 1930s.