From the 2009 Sept./Oct. issue of Sporting Classics.

Cody died last December—cancer, like so many other goldens—and I still can’t believe he’s gone. That’s for the end of the story, though. The beginning is far happier.

Balmoral’s Code of Honor. Cody. He was a present from my wife, back before she was my wife. It was December 1996 when Molly handed me a small box wrapped in holiday paper. Inside was a snow globe with a golden retriever holding a Christmas wreath in its mouth. Dunce that I am, I thought the snow globe was the gift. Molly had to explain that she’d reserved a puppy from a yet to-be-born litter, and that we’d bring him home in March.

In case there’s any doubt in your mind, that was the moment when I realized my wife-to-be was pretty damn incredible.

Cody was a light-colored ball of fluff when we picked him up from the breeder, and he had an obvious mohawk that started right above his eyes. The fluffy part went away. The mohawk stuck around. But funny hair or not, Cody was a prince. Other pups chew on your shoes and your furniture, chase the cat, knock over the garbage and scatter orange peels and coffee grinds all over the kitchen floor. Cody never did. He had so much fun exploring his new Montana home and playing with Panama, our yellow lab, that he never got into trouble.

“The old man has left me here in the truck and taken those other dogs to chase birds. My heart is breaking and I think I’m going to die.”

In fact, the only time Molly ever complained was when Cody started jumping on the bed and sleeping down by our feet. She still tells people about my habit of picking him up, settling him on my chest, then saying, “Now he’s not on the bed anymore,” before falling fast asleep.

As you might already have guessed, Cody grew into a bird-hunting fool. He simply couldn’t get enough. We chased pheasants and sharptails and huns and ruffed grouse, and it never seemed to bother him that I missed more birds than I hit. Other dogs might give you the “What’s up with that?” stare when all their hard work flew off for the next county. Cody didn’t mind, though. Not at all.

My friend Tim Linehan once summed up the sport of fly fishing. “The strike,” he said,“is everything.” Cody felt the same way about the flush. His sole focus was on his end of the deal. If the old man screwed up the shot . . . well, that’s what the old man always did. Of course, on those rare occasions when a bird thundered off and then veered into an errant string of pellets, Cody retrieved it with a combination of joy and swagger that you couldn’t mistake for anything other than sheer ecstasy.

I don’t think I’d be exaggerating if I told you that Cody was as handsome and regal a dog as I’ve ever seen. He was a touch big for a field retriever—85 pounds without an ounce of fat—but he always carried himself with grace and dignity. And there was something about him, some impossible to characterize depth-of-soul that impacted me at levels I can’t begin to describe. I’ve owned other dogs. I’ve loved other dogs. But I’ve never connected with another dog in such an elemental way. It’s almost as if the Good Lord decided to bless me—not with a perfect dog, but with my perfect dog.

I suspect that most of us have felt the same way at one point or another. The trick, if there is a trick to it, is in recognizing the rarity of the gift early on and then spending as much time as possible in each other’s company. Cody’s only flaw—and he had to have one; it was preordained—was that he liked to fight. Not only did he like to fight, but he was good at it. Consequently, we couldn’t hunt him with most other dogs. He was fine with Panama, and with our little golden Ceilidh, and with Tim Linehan’s female retrievers, but we just couldn’t run him with anyone else. Which was truly a shame.

Looking back, the most Godawful sound ever to plague a Montana hunting trip was a direct result of Cody’s propensity for getting in scraps. Cody and I were hunting with Rick Bass and his pointers, and it was Cody’s turn to wait in the truck. Rick and I were just heading off with Point and Superman when Cody began to . . . well, I guess I should call it a howl. It started out low and mournful and then it swelled into this incredible, never-ending crescendo of loss and betrayal. If we could have translated it to human terms, it would have been something along the lines of, “The old man has left me here in the truck and taken those other dogs to chase birds. My heart is breaking and I think I’m going to die.”

That operatic keening went on and on and on—I swear I could still hear it a mile away—and it was horrible. There’s really no other word for it. Cody sounded like he was going to expire from the sheer misery of the experience. He didn’t hold a grudge, though, and he was smiling and ready to hunt when we finally made it back to the rig a couple of hours later.

Lord, I miss that dog.

We think of ourselves as hunters, and of our pups as gun dogs. Yet as important as the hunting is—and make no mistake, it is important—the time we spend afield is only a part of it. There’s a bigger picture. It’s the tail thumps when we walk into the room, the gentle weight of his head on our knee, the absolute trust that shines in his eyes, the way that our hand seems to find his ear of its own volition. It’s the fact that, as every attentive dog owner knows, our dogs define the term “unconditional love.” Hell, if we had half their innate capacity for love—if we had a quarter of it—this magnificent world, which we treat with such studied indifference, would be a paradise.

All we can hope for is that we’ll eventually find the right balance; that the memories will come to outweigh the tears and the terrible sense of loss.

All of which makes it that much harder when they pass. Their light, that special glow that steadies and illuminates our lives, proves far too ephemeral and we’re left with the knowledge that a part of us—a huge, irreplaceable, irreducible part—is gone forever. There are no words that make it better. Nothing makes it better. All we can hope for is that we’ll eventually find the right balance; that the memories will come to outweigh the tears and the terrible sense of loss.

So I’m focusing on those memories—on the brilliant fieldwork and soft-mouthed retrieves, the innumerable games of fetch and frisbee, the swims in the creek, the quiet walks on the trails and dirt roads, the long rides in the truck, the million shared moments that made our world a brighter place and brought us so much joy. Because that’s all I have left. Memories.

Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust. They say it’s better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. I can’t doubt the honesty of those words. They ring true.

I’m thankful for my time with Cody. I truly am. He was a rare dog; a blessing from the day we brought him home until the day he died. But now he’s gone and I miss him. Day after day, week after week, month after month, I miss him. Sometimes, when I look up at the shelf where a plastic golden retriever holds a Christmas wreath in his mouth, it’s hard to breathe.

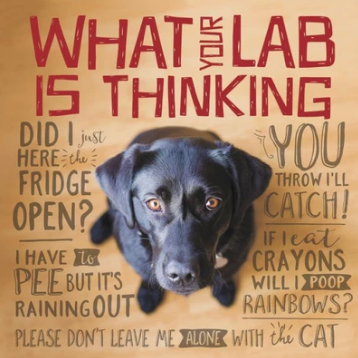

Labs are known for their furry snuggles, playful romping and soulful eyes; just think if they’re tongues were wagging instead of their tails! This playful little book is full of side-splitting inner monologues about a lab’s favorite things, the people they meet and places they go. The bold colors and lighthearted quips are paired with an array of adorable yellow, black and chocolate dogs and puppies, making this the perfect gift book for anyone who’s ever loved a lab. Buy Now

Labs are known for their furry snuggles, playful romping and soulful eyes; just think if they’re tongues were wagging instead of their tails! This playful little book is full of side-splitting inner monologues about a lab’s favorite things, the people they meet and places they go. The bold colors and lighthearted quips are paired with an array of adorable yellow, black and chocolate dogs and puppies, making this the perfect gift book for anyone who’s ever loved a lab. Buy Now