You can always follow water, whether it still runs free or is merely a latent image left behind in some dry, desert place.

From trickles to brooks to streams to torrents, water always runs down to its true source, there to be gathered into the air like so much brood and returned on the wind to the places where it once more becomes trickles and branches and torrents and streams.

Even when water has already run its course and is gone, as it so often does here in the high New Mexico desert where I awoke in darkness an hour ago, you can still follow its desiccated trail.

It’s empty path leads up from the cottonwood flats along the San Juan river and then out across the broad piñon- and rock-laced steps toward the base of the cliffs towering above as you follow the dry, sandy watercourse higher and higher and revel in the morning being born around you . . . which is exactly what I am doing at this very moment as the cool, blue, pre-dawn desert light hovers in a delicate balance between darkness and dawn.

In a place such as this, one is small.

Yet small is a good thing to be. For only by being small can you come and go from the holy places without intrusion, without disturbing or being disturbed, without being obtrusive.

Only when you try to be large do you no longer fit your insignificant niche and declare to all around you—man and beast and flower and juniper—that you are in fact an intruder, and therefore neither belong nor deserve to be here.

But if you can somehow learn to belong, there comes an evanescence to your spirit you might otherwise never know. The air and the land and the places where once the water flowed embrace you and seed your spirit with their own sanguine essence, revealing a part of themselves you could never experience on your own.

Then, in a moment of crystalline clarity and with a deep and abiding sense of the present, you suddenly recognize the perfect order that resides in the chaos that surrounds you, and you sense the utter realism of the fantastic.

The air is dry and clear here this morning as the world awakens around me, and for now at least it is relatively cool, providing a fleeting counterpoint to what it will be in just a few hours as the early August sun overruns the day and once more warms it to the point of oppression, when even the rocks will groan in the relentless heat.

Everything here that is alive, from the small desert lizards and skinks, to the songbirds and jackrabbits and mule deer, to the least little flower and cactus and bee, deserves the utmost respect simply for living and growing and singing and buzzing in a place such as this. I feel humble to be a part of the overwhelming silence that surrounds me, if only for this single mystical moment. An eagle is calling in the cliffs above.

This is most assuredly a holy place.

Now, as I climb the steepening slope and weave my way among the rocks and boulders and make my way up along a knife edge to the vertical base of the dry cliffs, the crown of the rising sun suddenly pierces the ragged edge of the sky along the rimrock high above, searing itself into my vision.

I turn away, and I can see my own insignificant shadow along the desert floor far below, and I watch in awe as the mountains eighty miles to the west come alive in the low light of dawn.

I really have no particular destination in mind as I climb, for I simply want to experience the beginning of this day in this place where I have never been, this place for which I have no prior point of reference, this place that is not mine but is even now etching its essence into my soul.

This brief, three-day interlude along the San Juan has been different from any other trout fishing I have ever experienced. On the first evening, after I got Jane and Carly settled in and they met my friend Gretchen Lee who owns the little cabin where we are staying, I headed alone upriver to the Texas Hole.

The Texas Hole is arguably the signature run on the upper San Juan, and it was here where I intended to first set foot in the river. But there were too many fishermen already there, some in the main channel and some waiting in line for their opportunity to work the choice spots. The early afternoon air was warm but surprisingly comfortable with its lack of humidity.

I found the only run I could see that wasn’t teeming with fishermen and went in alone upstream above the island. As I stood there rigging my standard Tennessee pairing, a CDC Caddis with a Fuzzy Worm dropper, I saw a trout rise in the flat water in front of me.

On my fourth cast he hit the Fuzzy Worm, attacking it as though he had never seen such a strange morsel. His size was small but his enthusiasm was high, and I released him with a smile as I realized he was my first trout from the legendary San Juan. A few casts later I caught another one on the same improbable little fly, a rainbow like the first.

Both trout were about eleven inches long and noticeably lighter in color than our trout back home. I wasn’t sure whether this was just an aberration or indeed the normal coloration of desert trout.

I could still see fish taking something off the surface, so after fifteen minutes I changed the little CDC Caddis to a #18 Parachute Adams, retying the Fuzzy Worm dropper two feet below it, then crossed the run where I took a small brown trout on the dropper.

It was clear that whatever they were taking off the surface was not very well represented by anything I had shown them so far, so I searched my fly box for something, anything, that might work. But in the end I settled on my little nymphs.

With dusk approaching, I looked downriver into the main run of the Texas Hole and saw that it was suddenly and surprisingly mostly empty of other fishermen, and I quickly moved down into the edge where the two main currents converge.

I tied on a new piece of 5X tippet with a weighted Carly-22 and trailed the Fuzzy Worm below it on three feet of fresh 6X, then cast slightly upstream and immediately threw a big looping mend even higher. At the end of the drift something significant tapped the line, and I struck too hard and broke off the entire rig.

Clearly he had hit the top fly, so I retied the same two-fly set up. Three casts later another fish again hit the top fly about halfway through the run, and this time I did not overtax the little three-weight on the strike and everything held.

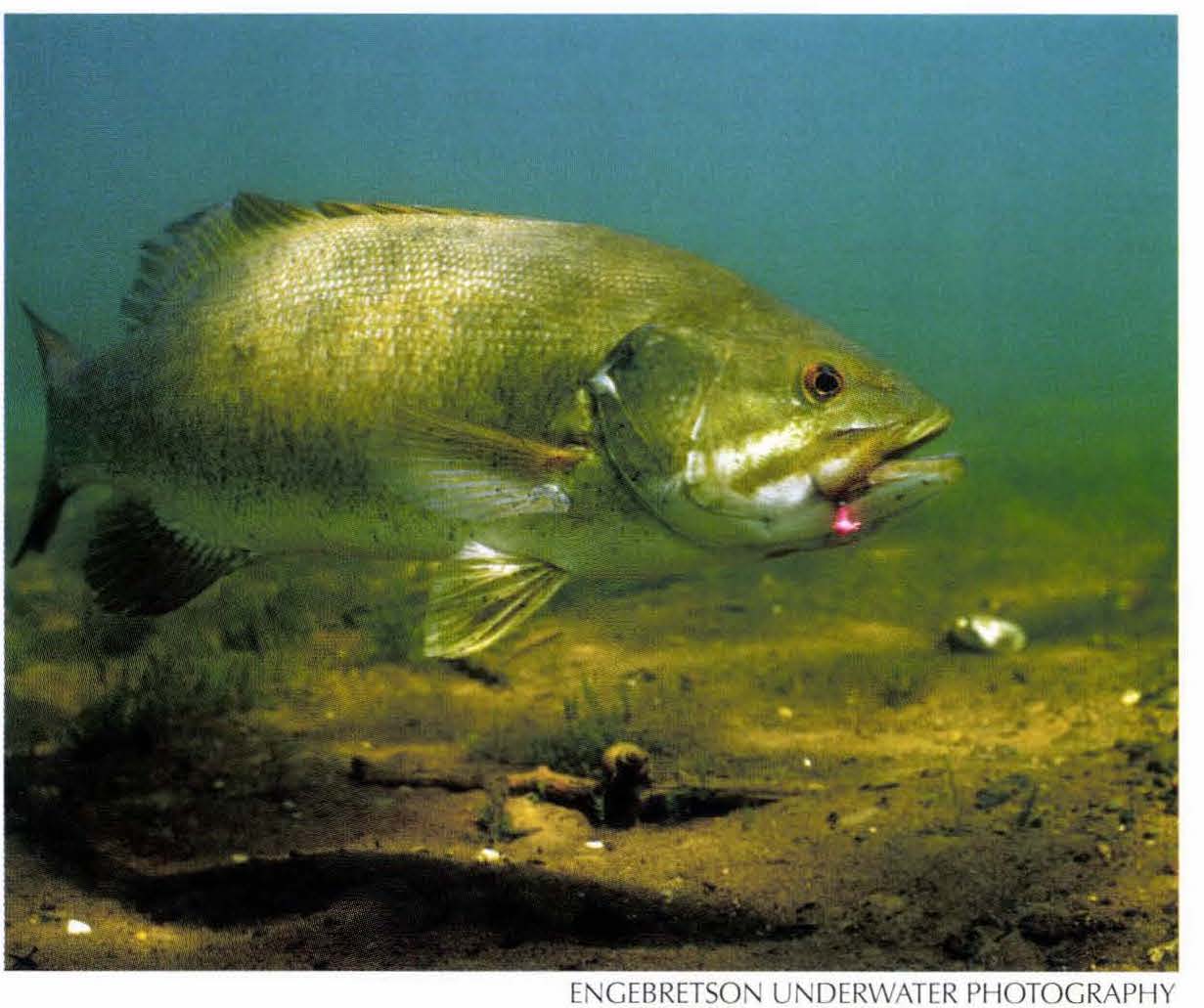

The trout flailed the surface in the waning light and then burrowed deep, heading crosscurrent and slightly upstream. I moved directly into the run, then down to my left to stay below him, and in the dimming shadows it wasn’t until he was actually in the net that I could see he was a rainbow. I estimated him at close to twenty inches, and even in the dusky light he seemed to be very pale in color.

As I released him, I realized that the few remaining fishermen had left and I was completely alone in this marvelous run on this classic river, with the evening entirely mine. For a moment I slipped my bottom fly into one of the guides of the rod, looped the long leader back around the reel, and just stood there in the shadows bathed in the soft sunlight reflecting from the warm cliffs above.

This one big trout had made the entire trip worth the effort. I was very pleased with the evening, having had these last few moments alone for my first foray on the San Juan. When I returned to the cabin an hour after dark, Jane and Carly and Gretchen and I sat outside and ate our supper and marveled at the clear, moonless sky and the millions of stars that vaulted the heavens from horizon to horizon.

In the morning we leave Navajo country, heading east and north into the land of the Jicarilla Apache, then up into the greening mountains and headwaters of the Brazos where our friends are waiting for us.

But for now I have one more day to explore the San Juan. And as I sit here alone at the base of Eagle Mesa in the amber glow of a high desert sunrise, I can see our little cabin a mile or so below to the south, and far beyond it the green, meandering cottonwoods that flank the river.

Two small figures, one in pink and one in green, just walked out and sat down in front of the cabin, and I think the one in pink just spotted me and waved.

Breakfast must be ready.

So am I.

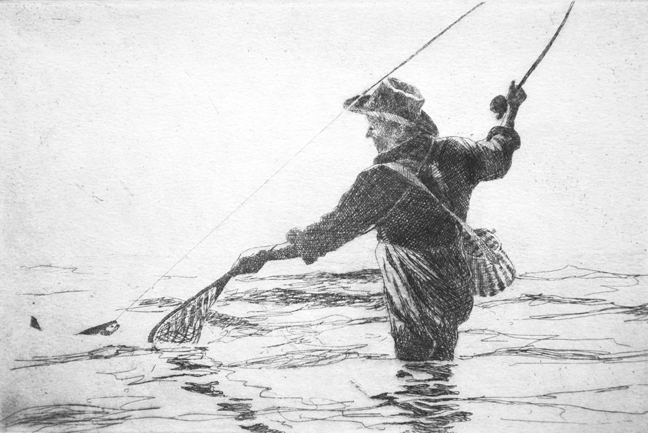

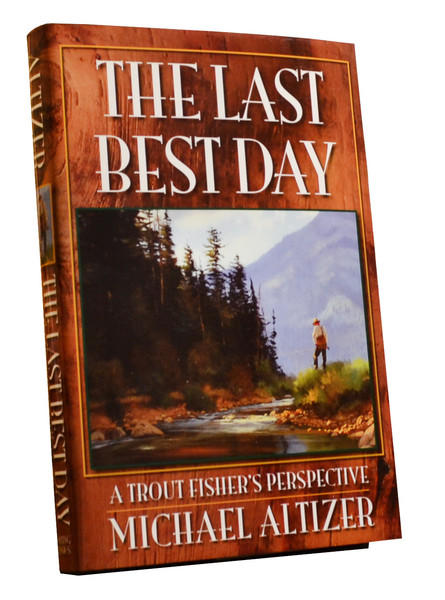

Thirty-five true-life stories covering the author’s fly fishing adventures from the creeks on the Appalachians to the high country streams of the West to the great salmon and trout waters in Alaska. 250 pages; illustrated by Brett James Smith. Buy Now

Thirty-five true-life stories covering the author’s fly fishing adventures from the creeks on the Appalachians to the high country streams of the West to the great salmon and trout waters in Alaska. 250 pages; illustrated by Brett James Smith. Buy Now