Mike Stidham, the critically acclaimed, self-taught artist, paints fishscapes.

One summer evening a year ago, Mike Stidham left his studio and drove a few miles to a heavily fished stretch of the Provo River where it spills out of the Wasatch Mountains through the outskirts of metropolitan Salt Lake City. Fly rod in hand, an energetic bounce to his 40-something step, he descended the stream bank to a long, deep channel where he talked briefly with several anglers about to head home with empty creels. Convinced that the pool held trout, Stidham quietly waded in and began methodically working several dark holes necklaced by smooth cobble. Almost as if by command, brown trout began rising from the depths to hammer his dry flies, raising eyebrows among the gathering crowd.

One summer evening a year ago, Mike Stidham left his studio and drove a few miles to a heavily fished stretch of the Provo River where it spills out of the Wasatch Mountains through the outskirts of metropolitan Salt Lake City. Fly rod in hand, an energetic bounce to his 40-something step, he descended the stream bank to a long, deep channel where he talked briefly with several anglers about to head home with empty creels. Convinced that the pool held trout, Stidham quietly waded in and began methodically working several dark holes necklaced by smooth cobble. Almost as if by command, brown trout began rising from the depths to hammer his dry flies, raising eyebrows among the gathering crowd.

Stidham, one might surmise, put on the impromptu clinic not only to affirm a personal connection with the subjects of his art, but as a reminder to startled onlookers that a river never sleeps. Good fishing water, he says, contain a world of mystery rarely discernible to the human eye.

Which, in a nutshell, is why Mike Stidham, the critically acclaimed, self-taught artist, paints fishscapes.

Art Bond, an avid fly-fisherman and owner of Western Wildlife Gallery in San Francisco, has wiled away countless days casting with some of the finest angling talent in the world — in the Rockies, the Caribbean and on the flats of Florida. “Mike Stidham is, without a doubt, the best fly-fisherman I’ve ever seen,” Bond says. “He can look at the water running down a gutter and tell you when the next hatch will occur and what it’s going to be. He has extraordinary patience, flawless insight and a feel for water that’s almost like a sixth sense.”

Art Bond, an avid fly-fisherman and owner of Western Wildlife Gallery in San Francisco, has wiled away countless days casting with some of the finest angling talent in the world — in the Rockies, the Caribbean and on the flats of Florida. “Mike Stidham is, without a doubt, the best fly-fisherman I’ve ever seen,” Bond says. “He can look at the water running down a gutter and tell you when the next hatch will occur and what it’s going to be. He has extraordinary patience, flawless insight and a feel for water that’s almost like a sixth sense.”

Like magic, Bond says, Stidham also has the rare ability of transferring his gift to canvas in a way that has made him one of the premier sporting painters in North America, eliciting comparisons to the legendary Richard Bishop, Frank Benson and Ogden Pleissner.

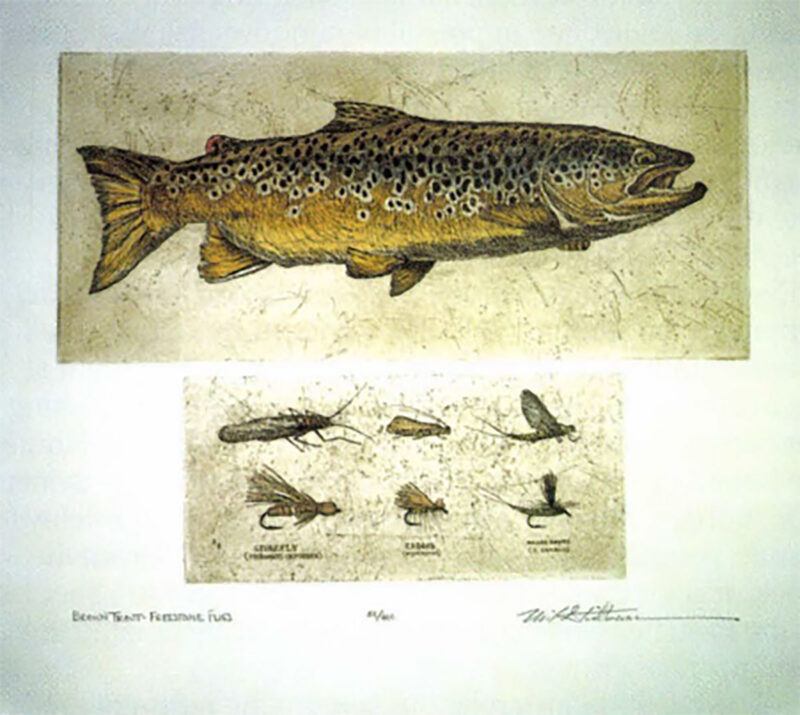

As a fine artist, Stidham aspires to elevate gamefish representation to a grand level of princely respect. He sets up his palette with the same prescience employed in narrowing fly patterns to match a hatch. And he believes his mission is not merely to render “fish pictures,” but to create paintings and etchings that transcend the subject. “I get asked all the time if I’m a wildlife artist or a sporting artist,” he says. “Just call me an artist. That will be fine.”

Adds Stidham, “When I first started painting fish and ducks and geese, I was so overwhelmed with trying to get the anatomy right I lost track of the larger view of art. Over the years my perspective has changed,” said the man who was commissioned to paint the newly published New Hampshire Atlantic Salmon Stamp for 1998. “Obviously you have to know the anatomy of your subject, but I’m not in the business of doing medical illustrations. My challenge isn’t to make a painting that looks like a fish, but to portray fish in a way that is worthy of a painting.”

Adds Stidham, “When I first started painting fish and ducks and geese, I was so overwhelmed with trying to get the anatomy right I lost track of the larger view of art. Over the years my perspective has changed,” said the man who was commissioned to paint the newly published New Hampshire Atlantic Salmon Stamp for 1998. “Obviously you have to know the anatomy of your subject, but I’m not in the business of doing medical illustrations. My challenge isn’t to make a painting that looks like a fish, but to portray fish in a way that is worthy of a painting.”

Today, Mike, his wife Kathy and their four kids (two boys and two girls) reside in a picturesque enclave of Salt Lake City, surrounded by the high Wasatch to the east, Great Salt Lake on the western horizon, and miles of trout streams. For the Stidhams, trout literally provide financial as well as spiritual sustenance.

Stidham is part owner of a clothing company, Wasatch Dry Goods, which sells t-shirts featuring his art and distributes them nationally to retailers such as Orvis, L.L. Bean and Nordstrom department stores. Recently, however, Mike has put these peripheral concerns on the back burner and devoted himself almost entirely to painting.

Nomadic from his roots, Stidham spent his early childhood in the bone dry Mojave Desert around Palm Springs, California, where his father, a contractor, plied the construction business. The trout bug bit when his dad was hired to build condominiums at the fledgling Snowmass Ski Resort in Aspen, Colorado, and the young Stidham spent a summer taking casting classes while fishing the storied Roaring Fork and Frying Pan rivers.

Nomadic from his roots, Stidham spent his early childhood in the bone dry Mojave Desert around Palm Springs, California, where his father, a contractor, plied the construction business. The trout bug bit when his dad was hired to build condominiums at the fledgling Snowmass Ski Resort in Aspen, Colorado, and the young Stidham spent a summer taking casting classes while fishing the storied Roaring Fork and Frying Pan rivers.

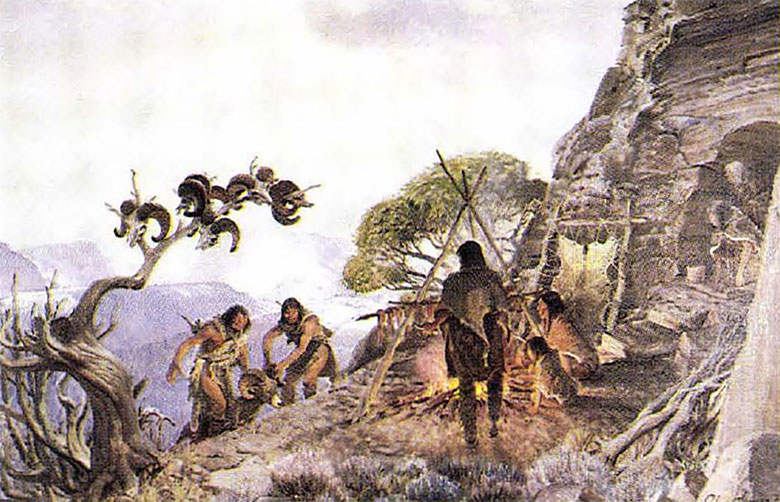

Not long thereafter, the family moved to Lake Arrowhead, California, and then to the little town of Bishop along the foot of the Sierra-Nevada. By now, spending every available afternoon knee-deep in pursuit of rainbows, his Waltonian convergence was complete when he was invited to join several friends who made regular pilgrimages to the Yellowstone country. In his impressionable mind, wading the Madison, Henry’s Fork, Gallatin and Yellowstone was like discovering the quintessence of paradise. And they would always draw him back.

Even while in high school, Stidham carried a sketchpad whenever he ventured into the outdoors, rendering small watercolors of barns and farm scenes and selling them at local art shows. His fledgling career as an artist and fishing raconteur, however, was sidetracked by a mission to Florida on behalf of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. For Stidham, the only belief more devout than his fidelity to family, painting and fishing is his fealty to God. Given the backdrop for trout waters in the West and saltwater species in the East, he seems convinced the Almighty created the terrain with fly-fishing in mind.

Following Stidham’s religious sojourn, he returned to his favorite rivers, fishing his way home to Bishop from the Rockies, but by then his folks had resettled in southern California. So he struck out for Yellowstone, eventually landing a temporary job guiding clients for Bud Lilly’s venerable fly shop in West Yellowstone, Montana. When he wasn’t guiding, Mike sold enough watercolors for Lilly to showcase his work in the store.

Following Stidham’s religious sojourn, he returned to his favorite rivers, fishing his way home to Bishop from the Rockies, but by then his folks had resettled in southern California. So he struck out for Yellowstone, eventually landing a temporary job guiding clients for Bud Lilly’s venerable fly shop in West Yellowstone, Montana. When he wasn’t guiding, Mike sold enough watercolors for Lilly to showcase his work in the store.

“One of the first artists I recruited was David Whitlock and that led me to Mike’s work,” Lilly says. “Together, Dave and Mike set the tone for fish art whose national popularity grew out of this region. The accomplished fish artists are great fishermen. They know the environment and imbue an emotion. Mike is one of the very talented artists of this small group; he’s made a real impression, not just on art, but on the sport of fly-fishing.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the foundation of Stidham’s following is a corps of enthusiastic collectors who share an affinity for sport fishing. In short, they’re angling fanatics. They range from middle-class families which proudly hang his limited-edition etchings on the wall to business executives who purchase original oils for the corporate board room and fireplace mantles at their second homes. Among them are actors Michael Keaton and Don Johnson.

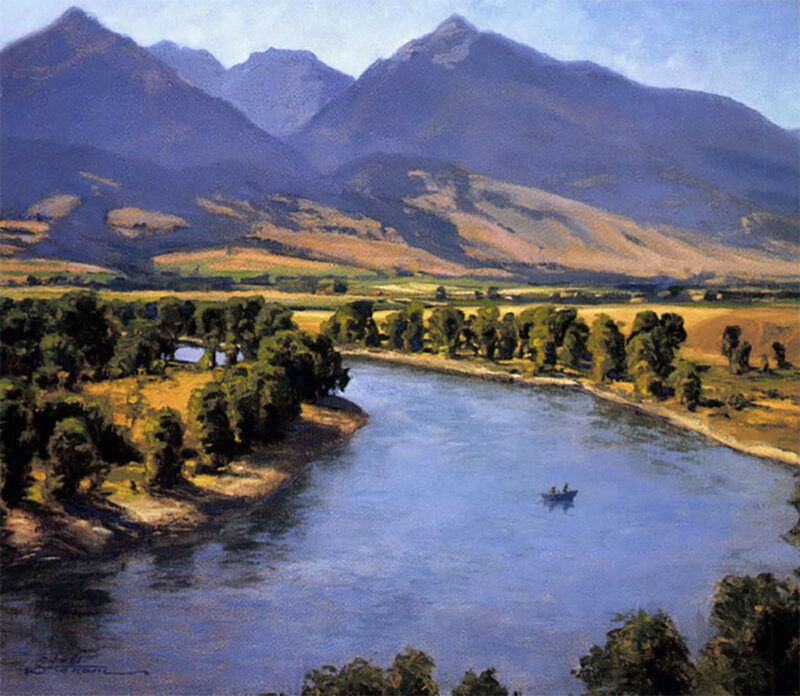

“The typical collectors are men and women who don’t have the luxury of going out fishing every weekend, but who want a beautiful daily reminder of what they really would rather be doing,” says Jim Brown, owner of Old Main Gallery in Bozeman, which serves as the main outlet for the artist’s work in the northern Rockies. “Mike’s pieces resonate with the viewer.” Although Stidham’s art could still be classified as realistic, his canvases are actually montages of abstraction that convey light, movement and color beneath the water’s surface. For him, the key to successful execution is design.

“I don’t think I’m consciously moving toward abstraction, but instead of conveying every little detail, what intrigues me more is distilling down the essential shapes and colors — to paint them sparingly. In the sporting art that I like, a strong statement is always one where you can’t add or take away from a good design element without upsetting the balance. That’s what I’m trying to do — find the balance between less and more.”

Stidham says the colorful paintings of Stanley Meltzoff made him aware of how marine subjects could be portrayed with a fine art flair. “After I saw one of his sailfish pieces in a magazine, I went to an art show in Laguna Beach that featured the work of California’s landscape impressionists. I remember looking at a sailboat painting by Edgar Payne, which glowed with light and held it in luminescence. I decided it would be fun to paint a permit that way, laying on the paint thick to capture the depth of color.”

Later, Stidham took a plein air painting course from landscape master Clyde Aspevig. “A real revelation that came out of that class with Clyde was that it doesn’t take a month to make a good painting.”

The length that Stidham will go to research a painting lends insight into his métier. During one memorable trip across the bonefish waters of southern Florida, he instructed the guide to treat his father to a day on the flats, while Stidham grabbed a towrope and slipped into the water behind the boat to observe fish habitat. “I spent the afternoon in a snorkel and mask, snapping underwater pictures and getting a flavor of the environment, but when I got home and developed the film, the photographs didn’t look anything like the images in my memory.” Stidham realized that he needed to skew his palette away from the soft, duller earth-tones of watercolors in favor of the effusive radiance of oils. “Obviously, every artist paints from a given point of view, but I decided that to convey the beauty of the underwater realm, I needed to present my own impressions rather than reproducing what the camera sees. It’s this interpretive approach that makes a painting interesting.”

The length that Stidham will go to research a painting lends insight into his métier. During one memorable trip across the bonefish waters of southern Florida, he instructed the guide to treat his father to a day on the flats, while Stidham grabbed a towrope and slipped into the water behind the boat to observe fish habitat. “I spent the afternoon in a snorkel and mask, snapping underwater pictures and getting a flavor of the environment, but when I got home and developed the film, the photographs didn’t look anything like the images in my memory.” Stidham realized that he needed to skew his palette away from the soft, duller earth-tones of watercolors in favor of the effusive radiance of oils. “Obviously, every artist paints from a given point of view, but I decided that to convey the beauty of the underwater realm, I needed to present my own impressions rather than reproducing what the camera sees. It’s this interpretive approach that makes a painting interesting.”

The most important element in a gamefish painting, Stidham insists, is an understanding of how light gathers and directs the eye. “Light has its own mechanics, which determine how atmospheric colors play and how the light comes through the lens formed by the surface of the water.

“My favorite saltwater fish is the permit, because I love its shapes and planes and its fluid movement. When you’re painting the flats of a bay where permit feed, the tendency is to think of the environment as static, but there are weeds floating a certain way with the tide and light bars are moving around, illuminating the turtle grass bottom. All you’re really trying to do in this setting is paint light and color, but without light there can be no color,” he says.

“Many people assume that the problem with painting blue water is coping with a limited palette, but there are ways to paint the color without using only blue. It’s fun to load your brush and walk your way through it.”

Editor’s Note: This excerpt is from, and can be read in its entirety in, the 1998 March/April issue of Sporting Classics.

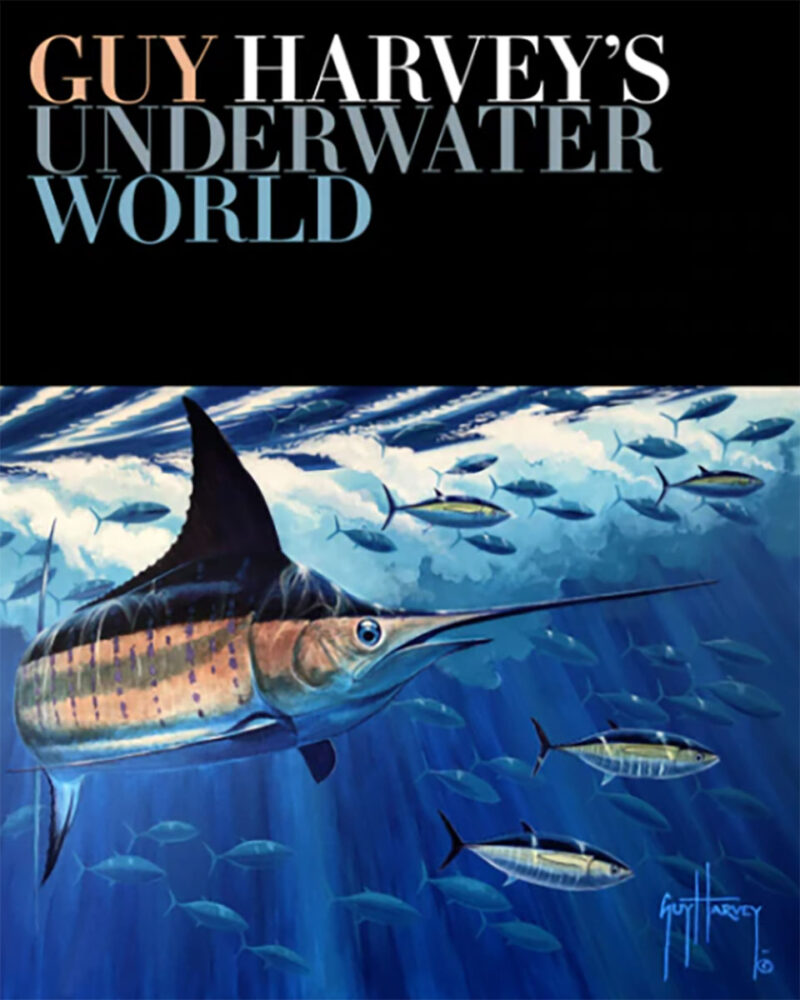

World-class angler, diver, photographer, and artist Guy Harvey shares his signature artwork, knock-out photographs, and fascinating stories of his time on and in the waters of the world. From Alaska to Australia to the Galapagos and beyond, Guy takes us along on the international fishing experiences of a lifetime.

World-class angler, diver, photographer, and artist Guy Harvey shares his signature artwork, knock-out photographs, and fascinating stories of his time on and in the waters of the world. From Alaska to Australia to the Galapagos and beyond, Guy takes us along on the international fishing experiences of a lifetime.

This strikingly beautiful, large-format book showcases Guy Harvey’s around-the-world fishing and diving adventures. Drawing from meticulous notes, knock-out photographs and Guy’s signature artwork, Guy weaves together fascinating stories, scientific discoveries and insights into the behavior of dozens of gamefish species to give us an up-close picture of his time on and in the water. Buy Now