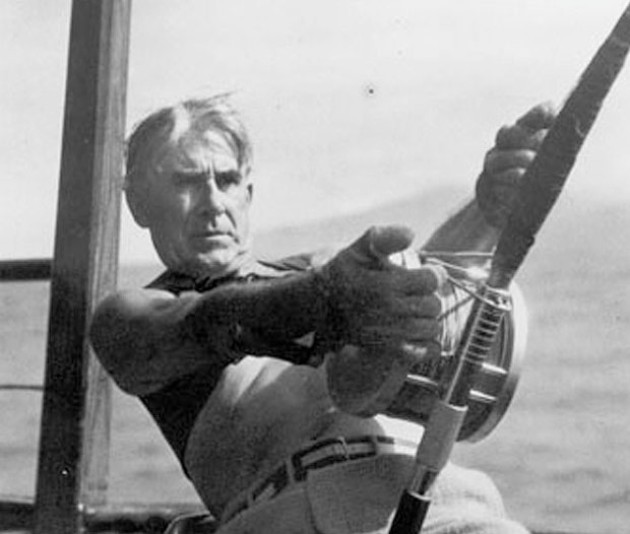

An excerpt from Grey’s Tales of Fishes, published in 1919.

It is very strange that the longer a man fishes the more there seems to be to learn. In my case this is one of the secrets of the fascination of the game. Always there will be greater fish in the ocean than I have ever caught.

Five or six years ago I heard the name “wahoo” mentioned at Long Key. The boatmen were using it in a way to make one see that they did not believe there was such a fish as a wahoo. The old conch fishermen had never heard the name. For that matter, neither had I.

Later I heard the particulars of a hard and spectacular fight Judge Shields had had with a strange fish which the Smithsonian declared to be a wahoo. The name wahoo appears to be more familiarly associated with a shrub called burning-bush, also a Pacific coast berry, and again a small tree of the South called winged elm. When this name is mentioned to a fisherman, he is apt to think only fun is intended. To be sure, I thought so.

In February 1915 I met Judge Shields at Long Key, and, remembering his capture of this strange fish some years previous, I questioned him. He was singularly enthusiastic about the wahoo, and what he said excited my curiosity. Either the genial judge was obsessed or else this wahoo was a great fish. I was inclined to believe both, and then I forgot all about the matter.

This year at Long Key I was trolling for sailfish out in the Gulf Stream, a mile or so southeast of Tennessee Buoy. It was a fine day for fishing, there being a slight breeze and a ripple on the water. My boatman, Captain Sam, and I kept a sharp watch on all sides for sailfish. I was using light tackle, and of course trolling, with the reel free running, except for my thumb.

Suddenly I had a bewilderingly swift and hard strike. What a wonder that I kept the reel from overrunning! I certainly can testify to the burn on my thumb.

Sam yelled, “Sailfish!” and stooped for the lever, awaiting my order to throw out the clutch.

Then I yelled, “Stop the boat, Sam! It’s no sailfish!”

That strike took 600 feet of line quicker than any other I had ever experienced. I simply did not dare to throw on the drag. But the instant the speed slackened I did throw it on, and jerked to hook the fish. I felt no weight. The line went slack.

“No good!” I called, and began to wind in.

At that instant a fish savagely broke water abreast of the boat, about 50 yards out. He looked long, black, sharp-nosed. Sam saw him, too. Then I felt a heavy pull on my rod, and the line began to slip out. I jerked and jerked, and felt that I had a fish hooked. The line appeared strained and slow, which I knew to be caused by a long and wide bag in it.

“Sam,” I yelled, “the fish that jumped is on my line!”

“No,” replied Sam.

It did seem incredible. Sam figured that no fish could run astern for 200 yards and then quick as a flash break water abreast of us. But I knew it was true. Then the line slackened just as it had before. I began to wind up swiftly.

“He’s gone,” I said.

Scarcely had I said that then a smashing break in the water on the other side of the boat alarmed and further excited me. I did not see the fish, but I jumped up and bent over the stern to shove my rod deep into the water back of the propeller. I did this despite the certainty that the fish had broken loose. It was a wise move, for the rod was nearly pulled out of my hands. I lifted it, bent double, and began to wind furiously. So intent was I on the job of getting up the slack line that I scarcely looked up from the reel.

“Look at him jump!” yelled Sam.

I looked, but not quickly enough.

“Over here! Look at him jump!” went on Sam.

That fish made me seem like an amateur. I could not do a thing with him. The drag was light, and when I reeled in some line the fish got most of it back again. Every second I expected him to get free for sure. It was a miracle he did not shake the hook, as he certainly had a loose rein most all the time. The fact was he had such speed that I was unable to keep a strain upon him. I had no idea what kind of a fish it was. And Sam likewise was nonplussed.

I was not sure the fish tired quickly, for I was so excited I had no thought of time, but it did not seem very long before I had him within 50 yards, sweeping in wide half-circles back of the boat. Occasionally I saw a broad, bright-green flash. When I was sure he was slowing up, I put on the other drag and drew him closer. Then in the clear water we saw a strange, wild, graceful fish, the likes of which we had never beheld.

He was long, slender, yet singularly round and muscular. His color appeared to be blue, green, silver crossed by bars. His tail was big like that of a tuna, and his head sharper, more wolfish than a barracuda. He had a long, low, straight dorsal fin. We watched him swimming slowly to and fro beside the boat, and we speculated upon his species. But all I could decide was that I had a rare specimen for my collection.

Sam was just as averse to the use of the gaff as I was. I played the fish out completely before Sam grasped the leader, pulled him close, lifted him in, and laid him down—a glistening, quivering, wonderful fish nearly six feet long.

He was black opal blue; iridescent silver underneath; pale blue dorsal; dark-blue fins and copper-bronze tail, with bright bars down his body.

I took this 36-pound fish to be a sea-roe, a gamefish lately noticed on the Atlantic seaboard. But I was wrong. One old conch fisherman who had been around the Keys for 40 years had never seen such a fish. Then Mr. Schutt came and congratulated me upon landing a wahoo.

The catching of this specimen interested me to inquire when I could, and find out for myself, more about this rare fish.

Natives round Key West sometimes take it in nets and with the grains, and they call it “springer.” It is well known in the West Indies, where it bears the name “queenfish.” After studying this wahoo, there were boatmen and fishermen at Long Key who believed they had seen schools of them. Mr. Schutt had observed schools of them on the reef, low down near the coral—fish that would run from 40 to 100 pounds. It made me thrill just to think of hooking a wahoo weighing anywhere near a hundred pounds. Mr. Shannon testified that he had once observed a school of wahoo leaping in the Gulf Stream—all very large fish. And once, on a clear, still day, I drifted over a bunch of big, sharp-nosed, game-looking fish that I am sure belonged to this species.

The wahoo seldom, almost never, is hooked by a fisherman. This fact makes me curious. All fish have to eat, and at least two wahoo have been caught. Why not more? I do not believe that it is just a new fish. I see Palm Beach notices printed to the effect that sailfish were never heard of there before the Russo-Japanese War, and that the explosions of floating mines drove them from their old haunts. I do not take stock in such theory as that.

As a matter of fact, Holder observed the sailfish (Histiophorus) in the Gulf Stream off the Keys many years ago. Likewise the wahoo must always have been there, absent perhaps in varying seasons. It is fascinating to ponder over the tackle and bait and cunning calculated to take this rare denizen of the Gulf Stream.

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly.

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly.

Though he made his name and his fortune as an author of Western novels, Zane Grey’s best writing has to do with fishing. There he was free from the conventions of the Western genre and the expectations of the market, and he was able to blend his talent for narrative with his keen eye for detail and humor, much of it self-deprecating, into books and articles that are both informative and exciting. Buy Now