A touchstone of Donaldson’s work is his ability to translate the feeling one gets in encountering tremendous volumes of open space.

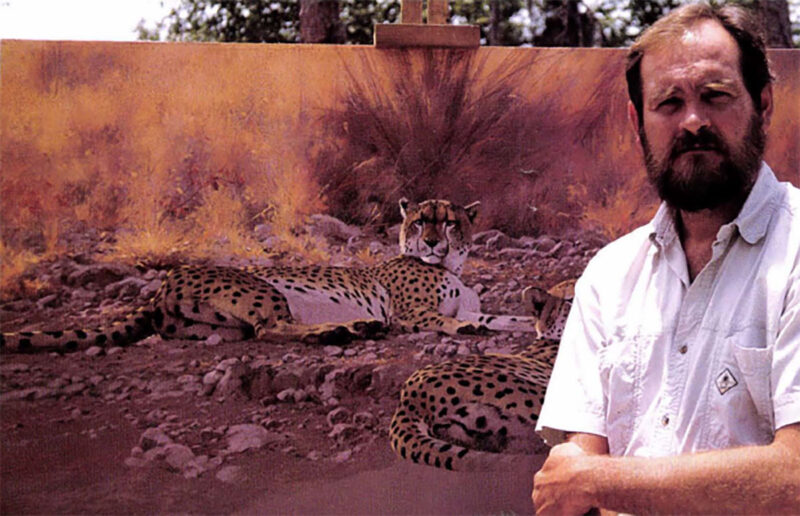

Africa-born Kim Donaldson moved his family to Florida’s southwest coast. On the easel behind him is Late Afternoon Light – Cheetahs.

Kim Donaldson could do nothing to prevent his eyelids from closing. His mind was drifting in and out of fitful sleep and his body, strained from a bout with African tick-bite fever, was succumbing to fatigue. Donaldson felt powerless. With dawn’s half-light creeping in upon a waterhole at Kruger National Park where he had set up his stake-out, all conscious awareness drained away into dreams.

He imagined the lumbering stilt necks of giraffe coming in for a drink; he saw a warthog charging straight into the oasis pool, dangerously oblivious to a pride of lions nearby. He pictured sable and jittery roan antelope inching their way toward a liquid surface that reflected a sky of cumulus clouds. And while still in deep sleep, he fantasized, too, about something he had done often — sketching game in a cloud of stirring dust.

For Donaldson, Africa always has been a place where dreams and reality merge into one. Sometime later he awoke to a stirring behind him in the back seat of his jeep. “I had this strange feeling that something was watching me,” he recalls. “The hair on the back of my neck stood up. As I turned around, there was a baboon staring me in the face. It got a fright and bolted out the passenger side of the vehicle. I got a fright and leaped out the other way.”

The episode was one that both primates lived to tell about, but Donaldson knew he was lucky Anything can happen in the bush, and it is this air of expectation that he constantly brings to the canvas.

To many collectors in Britain, southern Africa and the U.S., Donaldson is regarded as one of the premier painters of African wildlife. He paints with his guts, as they say, and he knows his subjects from years of stalking (and being stalked) in the wild. A native of the former Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Kim was raised on a “farm” that even by the standards of today’s western ranches would be large.

It would be easy to conclude, one could suppose, that an intrepid artist like Donaldson would be drawn to bold, brash oils and acrylics to capture the essence of a masculine, brooding environment around him. But what he has demonstrated convincingly is that every scene involves varying degrees of perception. When Donaldson wants to create a mood, he turns to a medium that most artists overlook: pastels.

“Pastel is nice because once you choose your color and put it down, the effect is immediate,” he explains. “It allows the viewer to be one step closer to the actual scene. The color you get is very rich and has a wonderful range. It’s something that is hard to find in other mediums.”

What makes Donaldson’s art particularly unique is that the works his pastels over an underpainting done in either acrylic or oil. “I honestly don’t know of any other artist who does this,” says Kim. “I do it to build up tonal values — black versus white and all shades in between — and to add more three-dimensional strength. It’s all a very lengthy process, but definitely worth the extra effort.”

While Donaldson’s pastels are crisp and realistic, compared to the hyper-realism practiced by most animal artists his work would border stylistically on impressionism. Only two other contemporaries are able to wield pastels sticks and crayons with a comparable degree of dexterity — Dino Paravano and Paul Bosman. Together, this three-some has held sway over the medium.

Scarlet Ibis

“Pastel has generally been regarded as a secondary medium,” Kim notes. “People who buy art tend to be afraid of pastel, believing it to be merely a chalk. They think that if you take a feather duster and wipe over the top of it, you might rub it all off. What they don’t realize is that once it is framed up with glass and a museum-quality mounting, it has as long a life, if not longer, than an oil painting.”

A touchstone of Donaldson’s work is his ability to translate the feeling one gets in encountering tremendous volumes of open space. When he paints a line of elephants moving along a sand river, the African veld stretching toward the horizon, we can comprehend the vastness of its grasslands.

But then, Kim Donaldson knows all about wide open spaces. Born in 1952, he grew up in the eastern highlands of Zimbabwe near the Mozambique border where the closest town of any size was forty miles away. The Donaldson clan came to the continent in a roundabout way. His great-grandfather, the family patriarch, was shipwrecked off the Cape Coast when South Africa was a British colony. A generation later, Kim’s grandfather made his way eastward and endured a failed attempt at starting an ostrich farm, but it did not dampen his spirit. Eventually he secured enough money to purchase a large tract of land, setting aside a small portion for crops and the rest to open rangeland for cattle and native fauna.

The plains and hills formed a major crossroads for wildlife. Leopard, giraffe, sable, impala, kudu, wildebeest — the short route to the game trails began not far from the front door of the Donaldson home. “I was very fortunate to have grown up in Rhodesia on a ranch, and that was my world before the politics of the country started going crazy,” he told me. “The country went through a stage when hunting and game culling got out of control, but fortunately the animals made a comeback.”

As a boy, Donaldson set out for the wilderness alone. “I think of the freedom I used to have to go out and hunt. We lived in a small town, but I would stay at the family ranch often for a week to ten days at a time.” The self-reliance and intuition honed in the bush, he says, enabled him to become a competent guide, and he helped visiting sportsmen fill out their permits for trophies. The insight that he brought to the hunt eventually found its way onto canvas, and although he stopped harvesting the quarry himself, he depicted animals through the mind’s eye of someone who lived among his subjects.

Peter Wilkins divides his time between a home in Zimbabwe and the art markets of Johannesburg. A former neighbor of Donaldson, at least in relative terms, he grew up hunting and observing wildlife the same way the artist did. Wilkins began selling Donaldson’s originals 15 years ago, and it did not take long before his art caught the attention of buyers at Everard Read, the premier gallery in Johannesburg. Word spread to England, and interest from the famed Tryon Gallery, which represents the likes of David Shepherd, culminated in a one-man exhibition.

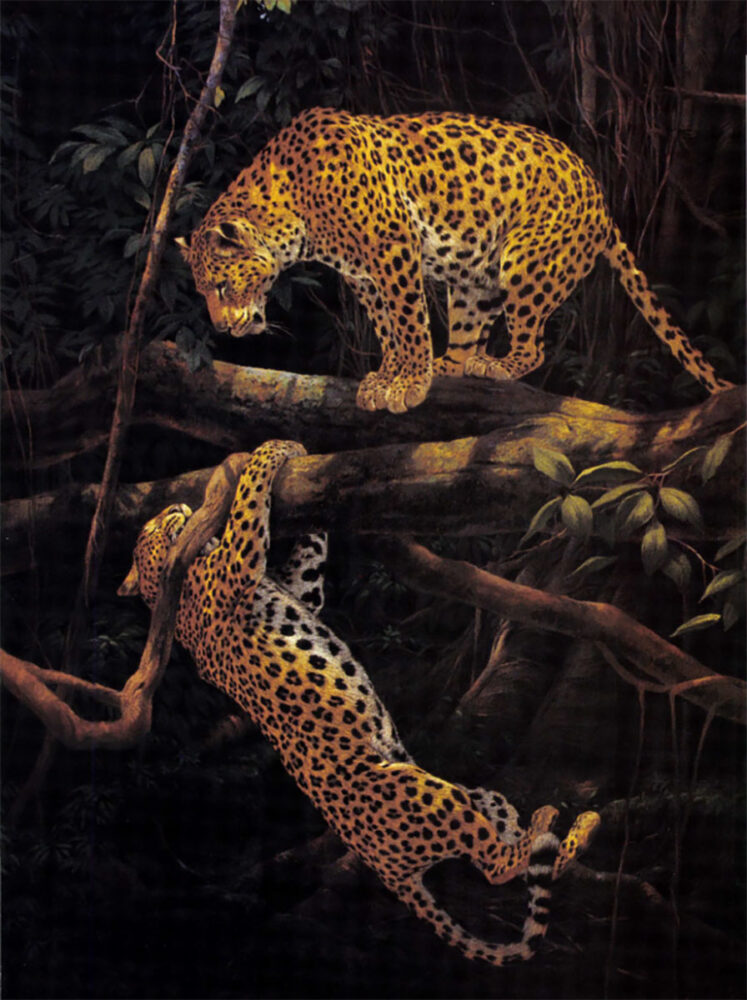

“I think there are three factors which the public likes about his work,” says Wilkins. “Kim manages to capture the atmosphere of Africa in a way that few other artists are able to do. Secondly, his paintings are always very accurate in terms of environment and anatomy. He doesn’t make mistakes and when he paints a leopard, it doesn’t look like a cheetah, nor does it have the wrong tree in the background. His environment is absolutely correct. Third, and most important, he understands the African bush so well. He was never a passive observer.”

A pair of courting leopards in Childish Lover.

With his youth piqued by the writings of Ernest Hemingway and African authors who made a career of hunting, Kim says his years of traversing a seemingly interminable land have humbled him. “I’m not a Hemingway, and I’m not a wild man. I’m a regular sort of person. I love wildlife, but by the same token I’m very respectful of it. I’m not a person who will go into the bush to deliberately get an elephant to charge, so that it will impress the people I’m with and give me a rush of adrenaline. There are a lot of silly people who will do it. I’m not one of them.”

When you’re dealing with a wide assemblage of large predators and virulent diseases that can kill quickly, there is no reason to go looking for trouble, he adds. The hunting guide-turned-painter can casually recite a handful of instances when he challenged the odds and took a chance, and other instances where a simple oversight almost led to disaster.

“One time along the Zambezi River I set up my tent beneath a big acacia tree. I failed to notice that elephants were browsing on the tree’s ripe seed pods. That night I awoke to a bull elephant browsing right above my head. He broke one of my tent ropes and the canvas fell down on me. I stuck my head out to see the elephant’s legs about two feet from my face! I was extremely frightened, but I knew if I remained still, he wouldn’t step on me. There have been documented cases of African soldiers sleeping out on the ground who have had entire herds of elephant walk right through their camps and no one was hurt or stepped on.

“With wildlife, there are measures you can take to avoid encounters,” he notes, after relating an incident in which he was treed for hours by a black rhinoceros. “But with disease, that’s something you cannot escape. By far, more people are killed by disease in Africa than anything else.”

Social upheaval, sweeping across many nations, hasn’t changed the way that he approaches the bush, but then again, Donaldson knows how to escape the crowds. “Generally, when I travel I’m getting away from everything. I’m not near the cities where there are problems. Still, the strife in Africa is a sad situation. To me, the Africa of my youth is as much about the people as it is the wilderness.”

Having painted most of the major wildlife venues in southern Africa, the 42-year-old artist is now challenged to create new glimpses of animals that have never been rendered. One of his works, The Celebration of Life, depicts the springtime ritual performed by springbok, a small plains antelope. With their legs locked straight and the hair on their backs fluffed up, the animals engage in a bouncing movement called “spronking” or ” pronking.”

The painting of springbok prompted Kim to ask how German legend Wilhelm Kuhnert might have approached this quirk of behavior and how he might have applied his own signature, making something so narrow be accessible to people who never have seen it happen.

“Kuhnert never relied on photography, which is what most wildlife artists, including myself, lean on so heavily these days,” Donaldson says. “Unfortunately, one of the reasons is the success and subsequent demand of ultra-realism. A lot of the creative touches of the artist are becoming of secondary importance to the print market, which is dictating a style of painting. Kuhnert was known as a person who could sit down and do a painting without having to make anatomical corrections. I doubt there’s any living wildlife artist who can do the same.”

Donaldson moved his family to a new home on Florida’s southwest coast. Even though he left Africa, the distance has given him a clearer direction in defining the critical elements which go into one of his paintings.

Toward the distant plains, as an evening procession of wildlife begins, winds pick up and dust devils skirt the horizon. A sky of diffuse light, clouded with haze and dust, becomes the color of pink Chablis. It is a verdant color that has nothing to do with plants. As Donaldson suggests: “I don’t like painting green.”

The ability to track light in a scene as it filters through the atmosphere is essential, but in Africa, the artist must also anticipate the projection of light as well as what’s already there. For example, grasping the way dust clouds run interference on white sunlight reaching the earth determines ultimately how an artist paints the fur of an animal’s coat or the subtleties of its posture.

Kalahari Lions reflects the broad range of colors Donaldson achieves in pastel.

Each autumn Donaldson returns tohis former haunts on research missions. There, in the half-dozen nations which comprise the Horn of Africa, it is the dry season, when wildlife congregate around the waterholes.

These are ecological hotspots, he says; the places where animals constantly interact. The ebb and flow of animals around these wetlands, typically at sunrise and sunset, is one of the few behavioral patterns that has remained constant over millions of years.

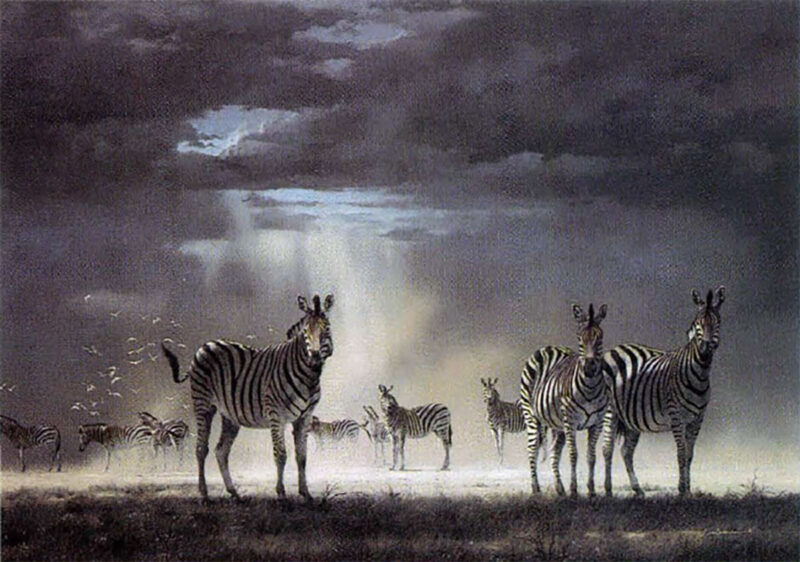

The waterhole motif has become synonymous with Donaldson’s name, and the stories behind the paintings have educated thousands of viewers about the importance of protecting these critical drinking areas. The Halcyon Gallery in England staged a one-man show featuring 42 of his originals, all inspired by the comings and goings of animals at six different waterholes. Donaldson gleaned his material from a five-week safari in 1992 that saw him traveling more than 7,000 miles across portions of South Africa, Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe. The portfolio from that trip includes portrayals of cats, zebra, antelope and birds.

Brewing Storm

“It is absolutely outstanding work because the pieces examine the watering holes at dawn, midday, late afternoon and evening,” says Lionel Green, who assists his son Paul in running the Halcyon Gallery. “The difference between Kim and a lot of other wildlife painters in Africa is the fact that he grew up there,” Green adds. “He lives it and breathes it. He knows the setting because once he hunted it. From this background, he understands the seasonality and atmosphere that must resonate from a painting, and it shows in his work.” Green said when the exhibition opened, collectors from Scotland to the south of England came to the show and praised Donaldson’s work, in particular his landscapes which de-emphasize wild life, but provide a context for the animal’s place in the environment.

Donaldson’s strongest sales have been in England and South Africa, largely because his art was introduced to the U.S. market only two years ago. The man responsible for making Kim’s work known to North American collectors is Ross Parker, who owns Call of Africa Gallery in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

American buyers, Parker maintains, have different tastes than the Europeans who prefer smaller paintings with animals presented as small pieces in the overall landscape. Collectors on this side of the Atlantic tend to favor large, super-realistic portraits that focus primarily on the Big Five. Europeans, with their longtime colonial tradition, are more knowledgeable about lesser-known species, while sportsmen here, particularly those who never have been on safari, are attracted to game animals that are eminently recognizable.

Experienced hunters here in the U.S. have demonstrated a strong interest in Donaldson’s paintings of Africa’s big game. In January the Dallas Safari Club in conjunction with Game Coin will host a show featuring Donaldson’s original, Year of the Hunter. Two of his paintings will also be displayed at the Houston Museum of Natural History where an exhibition sponsored by the Endangered Species Media Project opens in March. And in 1996 Call of Africa Gallery plans to do a major show with fellow Zimbabwean Craig Bone and the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach.

Ross Parker has done especially well with Donaldson’s large originals, some measuring as wide as six feet. In 1993 several works, priced between$22,000 and $29,000, were quickly scooped up. As for prints, Parker and his company, Environmental Art Awareness Group Inc. Publishing, releases only one Donaldson image per year in a marketing effort aimed primarily at a small audience of more sophisticated and educated collectors.

“We’re not in the business of mass-producing prints,” Parker maintains, “and we keep our editions small, usually about 450. As far as I know, we’re the only company that combines serigraphy (a form of silk-screening) with Advanced Continuous Tone lithography on a very heavy, top-quality stock. With regular offset lithography you can print about 5,000 colors, but with ACT you can do up to 25,500. This enables us to create an image that is almost100 percent true to the original.”

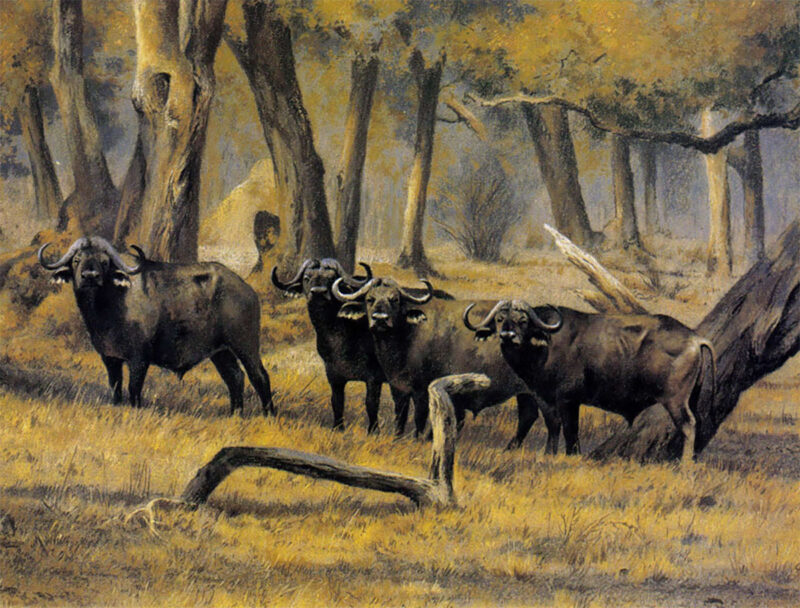

Buffalo at Mana Pools, a dramatic result of his many hours observing wildlife at waterholes

throughout southern and Eastern Africa.

“I don’t think anyone in the world can paint a lion better than Kim,” says Parker. “It seems like an easy subject to paint, but the problem is the long mane around its face. Many painters end up with a mane that looks as if its been blow-dried. Others have trouble with the face being too stubby or too elongated, or they make the lion look too pretty When Kim paints a lion, he creates a scarred, hardened face, and a mane that doesn’t look all combed out. It’s a lion that seasoned hunters who have traveled to Africa will appreciate.”

For Donaldson, there is no telling where his next African travels will take him artistically He returned again last fall and will unveil a newline of pastels in the spring. Many stateside collectors have eagerly embraced rumors that Kim may add North American wildlife to his portfolio. “I honestly don’t know where my art will go from here,” he says, suggesting that on his horizon there always is the prospect of a better painting.

“Regardless of where I live or paint, Africa will run through my blood. To me, wild Africa is the best place on earth. It’s something I want to share with the world by recording it before it’s gone.”

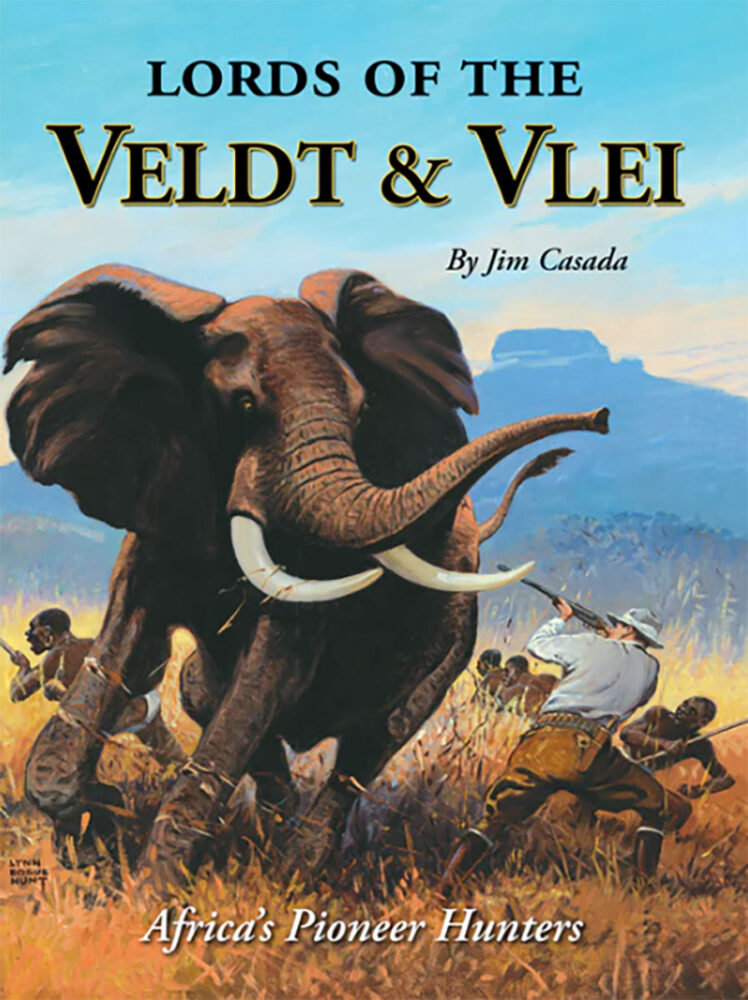

This account looks at some of the mightiest and most mesmerizing of these Nimrods, chronicling their careers while highlighting their eccentricities, delving into the factors that drove them, and sharing their achievements. Each profile is accompanied by a selection from published accounts by these pioneers of African sport, and dozens of vintage photographs and captivating pieces of art that offer a striking visual accompaniment to this saga of splendid sport. Buy Now

This account looks at some of the mightiest and most mesmerizing of these Nimrods, chronicling their careers while highlighting their eccentricities, delving into the factors that drove them, and sharing their achievements. Each profile is accompanied by a selection from published accounts by these pioneers of African sport, and dozens of vintage photographs and captivating pieces of art that offer a striking visual accompaniment to this saga of splendid sport. Buy Now