Cleverly designed and impeccably made, the guns and rifles, clothing and accoutrements of British craftsmen have influenced sport the world over.

We can be justifiably proud that we are the greatest melting-pot nation in history. Our willingness to absorb characteristics from virtually every human culture makes the United States a microcosm of the world.

But we began as a colony of the British Empire, history’s most influential political and social system. The Empire itself is gone, victim of its best philosophical concepts and worst social manifestations, but its influence remains – nowhere more thoroughly ingrained than here and in no sphere more apparent than sport.

We transformed some traditional British sporting games, evolved the elegance of baseball out of the complexity of cricket, turned soccer into football. As American sports, tennis and golf remain largely intact in the forms we inherited from our British ancestors.

More importantly, we inherited the British concept of what sport means. As they put it, sport is not so much a contest of skill or will as a demonstration of character. We, as is our way, express it a bit more bluntly: It’s not whether you win or lose but how you play the game. And despite the insistence of a few notable clodpates that winning is everything, we continue to embrace the notions of fair play and respect for the rules of the games.

The field sports represent the most pervasive British legacy, not only in the United States but worldwide, and not only in concept but in equipment as well.

Some traditional British sports endure here largely as curiosities. Riding to the hounds – “hunting,” the British call it – is one such. In the East it is the purview of those who can afford the not inconsiderable expense of maintaining horses and hounds. We in the West take a somewhat rougher approach and, lacking a reliable supply of foxes, chase coyotes on hard-driving quarter horses. In either case, as in England, it’s more about horsemanship and houndsmanship than about bagging a quarry. More often than not, the fox or coyote is the victor, and nobody really gives a damn, expect perhaps the dogs. The sport lies in the chase, never in the kill.

On a broader scale, flyfishing is a British import, from trout to salmon, tackle to trim. In fact, virtually every traditional featherwing salmon fly pattern is a British design, their bright, intricate beauty originating from the old notion that Salmo salar, the Atlantic salmon, feeds primarily upon butterflies. The biology may be faulty, but the patterns would delight any lepidopterist – and without a far-flung empire as a source for exotic, colorful feathers, they could never have existed at all.

On the broadest scale, the British gave us what we call “hunting.” In Britain, the pursuit of large animals with rifles is called “stalking.” By any name, it is the same the world over, and even though the British have no particular claim on the techniques, they certainly influenced the equipment. The 19th-century British sportsman or explorer traveled to what literally represented the ends of the earth, in both Africa and Asia, and for the large and formidable animals he found there, the British gun trade developed the big-bore double rifle. It has since become virtually a British signature as the tool of choice for dangerous game. James Purdey coined the term “Express” to describe the modern cartridges.

Griffin & Howe and others who followed largely defined the classic American design of rifle stocks, bolt-action and single-shot alike – and the classic Griffin & Howe evolved directly from the British stalking rifle.

Bird hunting, anywhere in the world, is essentially a British invention. A digression is in order here, because there is some truth in George Bernard Shaw’s observation that the British and the Americans are similar peoples separated by a common language. As I said earlier, “hunting” in Britain means riding to hounds. “Shooting” means firing shotguns at driven birds, and “rough shooting” is what we call “bird hunting,” which is done on foot. Rough shooting might include the company of dogs, or it might not; either way, it’s hunting to us.

It’s impossible to overestimate the extent of British influence on bird hunting in America – or anywhere, for that matter. The hard part is deciding where to start.

Having one draped across my feet as I write this, I’ll start with dogs. Is it merely accident that the classic breeds are English setter, English pointer and English springer? The Labrador retriever is named after a province of a former British colony, and its ancestors came from Britain. Golden retrievers and Gordon setters originated in Scotland, Irish or red setters, in Ireland.

Even the demonstrably American Chesapeake Bay retriever came from British antecedents. The German shorthair has been transformed from a so-called “versatile” (read that as “Jack of all trades, master of none”) to a brilliantly clever pointing breed by a healthy infusion of English pointer blood. Brittanies, the only pointing spaniel, owe more than a little of their innate abilities to ancestors that looked suspiciously like English setters.

Much as I love the traditions and challenges of British-style driven shooting, I love more to simply watch the dogs. On a really elaborate shoot, every gun has his own picker-up, who for all practical purposes is a dog-handler. The dog – Lab, springer, golden, flatcoat, whatever – sits calmly at heel during every drive, watching pheasants and partridges fall here, there, in front and behind. Neither handler nor dog moves until the gamekeeper calls “All out!” to signal the end of the drive.

Then it’s gangbusters. At a hand signal, a silent whistle, or a command spoken so softly that only the dog can hear it, the process of picking up begins. If the gun is a good shot and has drawn a particularly brisk stand, the handler will augment the dog’s memory of where the downed birds are, but even that is performed in virtual silence and perfect harmony.

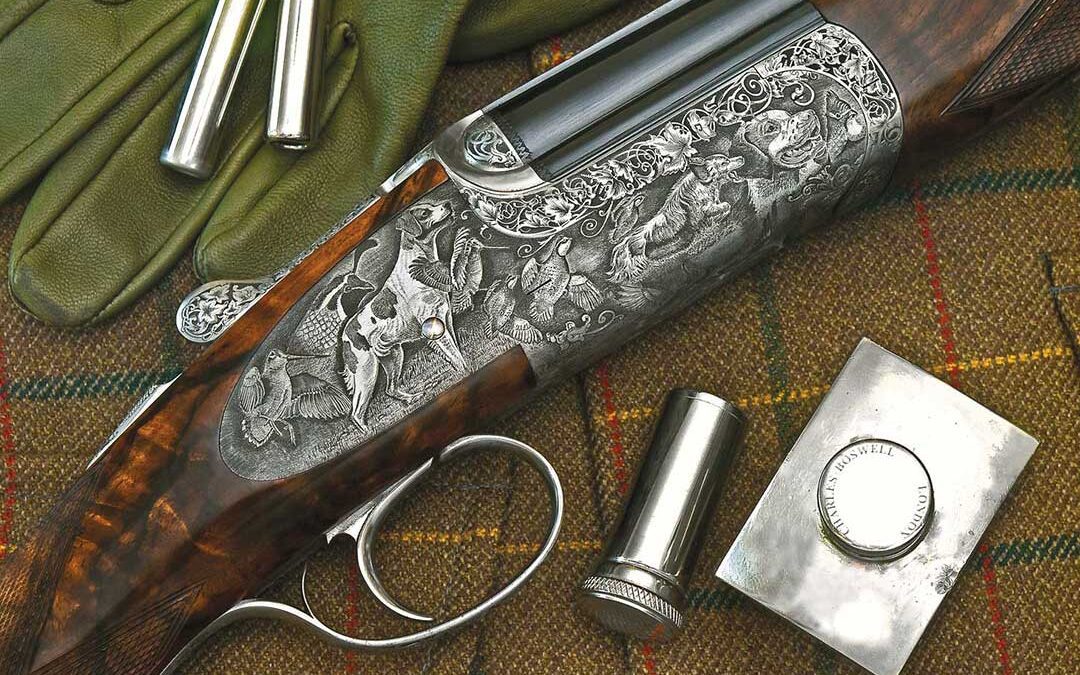

Birds and dogs together are training exercises. Add a gun, and it becomes hunting. It’s no exaggeration to say that the classic game gun is a British invention, even though the principal concepts came from the French.

The sport itself – tir au vol, shooting flying – was originally French. King Charles II took it to England in 1660, when he returned from exile to restore the monarchy after the English Revolution and Cromwell’s tragically prophetic Commonwealth Interregnum.

From France also came the break-action breechloader and the self-contained cartridge, respective inventions of Messrs. Lefaucheaux and Houllier. Both arrived in England about 1850 as concepts with great potential, and over the next 50 years British craftsmen transformed every aspect of that potential into perfection.

Griffin & Howe in New York offers this Purdey Best Ejector Hammer Gun with top tang safety. It’s built in 12 and 20 bore.

By the turn of the 19th century the Manton brothers, John and Joseph, had established a standard of quality in gunmaking that in time would be known simply as “London Best.” The Mantons presided over the ultimate perfection of both the flintlock and caplock muzzleloaders, and their disciples would become the first great generation of modern British makers. James Purdey, William Greener, Thomas Boss, Charles Lancaster, William Moore, William Gray and other former Manton workmen all eventually set up in business on their own, and through them the London gun trade became preeminent throughout the world.

Harris Holland was a notable exception in that he never worked for the Mantons nor for any of the former Manton craftsmen. He was, in fact, not a practical gunmaker at all, but rather a wholesale tobacconist – but his interest in shooting and guns soon led him to commission guns from outworkers to the London trade that he subsequently sold under his own name. Holland ultimately hired workmen of his own, to whom he apprenticed his nephew Henry Holland, and in 1876 the firm of Holland & Holland was born.

Purdey and Boss in particular carried the Mantons’ insistence upon perfect craftsmanship into the modern era, and their work rightly became the standard by which gunmaking worldwide is judged even to this day. Many others contributed mechanical elements that ultimately combined to create the modern game gun as we know it. W&C Scott, Thomas Southgate, John Stanton and Westley Richards & Co. were especially influential. In 1875 William Anson and John Deeley, who worked for Westley Richards, created an entirely new system that would become a standard in itself – a break-action gun with lockwork mounted inside a boxlike frame and cocked by leverage from the barrels. We know it now as the boxlock.

In the other standard form, in which lockwork is fastened to removable sideplates, Holland & Holland proved most influential. Nowadays, virtually every side-by-side sidelock gun built anywhere in the world – be it Belgium, France, Spain, Italy or elsewhere – is made after the pattern of the Holland & Holland Royal Ejector. The Holland sidelock action is standard even in the British trade. The exceptions are those makers who developed proprietary designs of their own; of these, Purdey and Boss are the most famous.

Not all boxlock guns are built strictly according to Anson & Deeley mechanics, but all boxlocks derive from the Anson & Deeley concept, as manufactured even now by Westley Richards.

John Dickson & Son, of Edinburgh, contributed yet a third form, in which the lockwork is fastened neither to sideplates nor to the frame, but rather to the triggerplate, after the German blitz-action concept. What began in the 1880s as the Dickson round action has since become a Scottish signature, still manufactured by Dickson & MacNaughton and by the premier Scottish craftsman of all, David McKay Brown.

By the turn of the 20th century there was nothing left to improve. Ejector systems, self-opening actions, single triggers – whatever refinement could be applied to the side-by-side game gun had been invented, reinvented and ultimately perfected.

The late Victorian Era was the cradle of what we now recognize as British style. The Empire was at its height, British influence felt worldwide. And in that time existed a phenomenon that had never existed anywhere before, and has not existed since. It was a social system centered specifically upon the gun and shooting.

Edward Albert, Prince of Wales, was Victoria’s eldest son, heir to the throne, arbiter of fashion, and doomed for the first 60 years of his life to do nothing except what pleased him. The Queen permitted him no role in British politics and herself refused to participate in the activities of British society. That task fell to the Prince, and the Prince was mightily fond of shooting.

Physically as unsuited to rough shooting as he was to riding, Prince Edward was the central figure in what has since become the classic British shooting sport – driven game.

In the 1860s the Prince visited Hungary as the guest of Baron Hirsch and there was entertained with shooting in the manner of the traditional European battue, in which game was driven over the guns. Legend has it that upon his return to England, the Prince decreed that this was how shooting would be conducted on the Royal estates.

English gamekeepers already knew how to rear pheasants, which the Romans introduced to Britain. The native red-legged partridge still existed in healthy populations, and they, too, were amenable to being pen-reared and released. Red grouse abounded on the heathered moors of Scotland. Apart from red stag and the odd wolf surviving in the remote Scottish Highlands, no big game remained in Britain. Bear and boar belonged to memory; what shooting might be done would be built around birds.

The wealthiest classes were more than happy to follow the Prince’s lead in diversions and pastimes, and by the 1880s shooting was all the rage. Virtually every country estate became a shooting ground, and the gentry vied among themselves to present not only the best of sport but elaborate entertainments to surround it. Weekend shooting parties became extravaganzas of costume balls, concerts and dinners of a scale scarcely seen since the days of Henry VIII. The sheer expense of such excesses was enough to bankrupt more than one great estate.

A wealthy upper class bent on embracing shooting and all it entailed created a demand for fine guns, clothing and other accessories unheard-of before or since. As the political, financial and social center of the Empire, London was the source for the best of everything. By the turn of the century, Westminster and its fashionable districts of Mayfair and St. James were home to suppliers of bespoken goods who could scarcely keep up with the custom of the carriage trade.

There were gunmakers by the dozen – Purdey, Holland, Boss, Woodward, Lancaster, Westley Richards, Henry Atkin, Joseph Lang, Stephen Grant, Rigby, Beesley, Wilkes, Bland, Greener, Churchill, Cogswell & Harrison, Hussey, Hellis, Watson Bros., on and on.

The British gave us the gun – and rifles made along similar lines for dangerous game – and they gave us wonderful sport. Driven game is a form of shooting that has been criticized and even ridiculed – invariably by those who’ve never done it and who only imagine what it’s like.

“Wholesale slaughter,” they sneer, “killing without hunting,” wrapping themselves in self-righteous disdain, as if nothing could be easier than shooting a bird that has been driven overhead.

I would love to put these numbskulls into a grouse butt in Scotland or Yorkshire, or on a pheasant drive in Somerset or Devon or Cornwall, and let them show me just how easy it is to take an honest right and left out of a pack of grouse strafing the contour of the moor at 70 miles per hour or do the same with pheasants flying almost as fast 40 or 50 yards above the guns.

The British gave us the techniques to do that, too – not to make it easy, because it isn’t even for the most skillful shot, but just to make it possible. American sportsmen, by necessity, evolved as riflemen; only within the past 15 or 20 years have we started to become true shotgunners, appreciative of owning a gun that fits, which is simply one that shoots where our eyes are looking when all we do is raise it to our cheek. Appreciative, too, of instinctive techniques that make optimal use of our natural ability to point our hands where our eyes look.

During the heyday of shooting in the late 19th century, the tailors in Saville Row, the Mayfair Street already famous for custom-made clothing, were swamped with orders for shooting tweeds. Because of differences in social structure, geography and the game, our hunting traditions evolved along somewhat different lines, and we consequently tend to think of traditional British shooting wear as some essentially eccentric form of costume. Far from it. Keeping in mind that high-tech, man-made fabrics and other materials did not exist in the latter part of that century, British shooting garb could hardly be more practical.

In a damp northern climate, wool still has no serious rival as a means of staying warm. Tweed, moreover, colored with dyes and woven to resemble the texture of heather, is the oldest example of camouflage clothing worn for sport.

But what about the funny, old-fashioned-looking knickers? Well, for one thing, we can call them “knickers,” but in Britain they’re known as “breeches” or “breeks.” There, “knickers” denote the feminine undergarment we usually call “panties,” so don’t be surprised if you get some odd looks if you refer to knickers as part of your shooting kit. Besides being eminently practical, well-cut breeks are about as comfortable for walking as anything you can find.

For that matter, no footwear can beat the knee-high rubber boots, named after the Duke of Wellington, for slogging around in water and mud, and if you expect to walk comfortably in them, wellies need to fit snugly in the ankle and calf, or pipe. Try stuffing the bottoms of full-length trousers in there, and knee-length breeks with thick wool stockings suddenly make a whole lot of sense.

Even on a drier day, when you might be inclined to forego the wellies in favor of traditional shooting brogues (shoes we typically call “wingtips”), walking or stalking in dewy heather will soon turn trouser legs uncomfortably wet. A veteran Scots ghillie is like to carry two or three pairs of stockings, and if you ask him why, he’ll point out that changing stockings is less trouble than changing trousers.

You can go whole-hog and have an entire shooting suit – breeks, jacket and waistcoat – custom tailored in England by such specialists as Norton & Sons or Haggart’s of Aberfeldy. Holland & Holland in New York is a good source, too. Or you can pick and choose among ready-made goods in this country at Griffin & Howe or from British Sporting Ltd. I don’t know who currently imports Christopher Dawes’ clothing, but if you find it, buy it. It’s good.

A shooting jacket made of waxed cotton invariably is my choice on any cold, windy, rainy day, regardless of whether I’m wearing breeks or brush pants. Waxed cotton garments were invented by seamen and farmers in Scotland and the English North Country. The British climate is not well-suited for growing cotton, but as with the feathers for dressing salmon flies, the empire provided ample supplies of wonderful, long-staple cotton fiber that could be woven into fine-textured fabric. Treated with a waterproofing compound based on beeswax, the result was as nearly impervious to weather as a garment can be.

I know for sure that it’s the best stuff there is for the essentially contradictory tasks of repelling water from the outside and still remaining breathable. Some high-tech materials purport to do the same thing, and I’ve tried them. Some people think they’re great, but I’ll take waxed cotton any day.

What started as purely practical has since become integral to our sense of fashion. Heading out on a rainy or snowy day, I’ll put on one of the half-dozen or more waxed-cotton coats I’ve accumulated, just to stay dry. But on an occasion that doesn’t demand ultimate formality, I’m most likely to show up in a tweed jacket, a tattersall shirt, club-pattern necktie, twill or whipcord trousers and wingtip shoes. We think of it as everyday dress, appropriate for anything from a corporate office to a cocktail party. Fact is, every single element originated as British country clothing. You could show up at a clement-weather shoot anywhere in Britain wearing exactly that and be appropriately dressed.

If what we wear and what we do with a flyrod or a gun is essentially British in origin, how we get there owes something to the British, too. What current SUV, after all, is not the spiritual descendant of a Land Rover?

And at the end of the day, what better tribute to the game we’ve pursued, and the sportsmanship with which we’ve done it, than a dram of good Scots whisky? Regardless of whether your taste prefers the light, subtle flavor of a Speyside, the rich, seaweedy tang of an Islay malt, or something between, it’s a drink not just in honor of a day but of a whole tradition that has permeated our culture in ways we scarcely imagine.

Editor’s Note: “Unmistakably British” originally appeared in the 2002 September/October issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

Sporting Purveyors