Tyee is the Indian name for a salmon of 30 pounds or more. No one has come very close to the mark.

It seemed to make sense. From the time of the early Indians, Barkley Sounders have called a 15-pound or better chinook salmon a “smiley.”

Maybe the smiles would come later for John Cornett Jr. Right now, his jaw muscles are knotted and his lips are a hard tight slit as he strains to slow the reel-smoking runaway on the end of his line.

The smiles are on the other end of the boat where Don Toeynan and I share the twisted pleasure of seeing our fishing companion in panic-laced misery.

We had talked about all this in the Beaver float plane that brought us from Seattle that morning. Don is a regular at Canadian King Lodge, attracted year after year by the fun and challenge of deep-water fishing for king salmon in the waters surrounding the lodge.

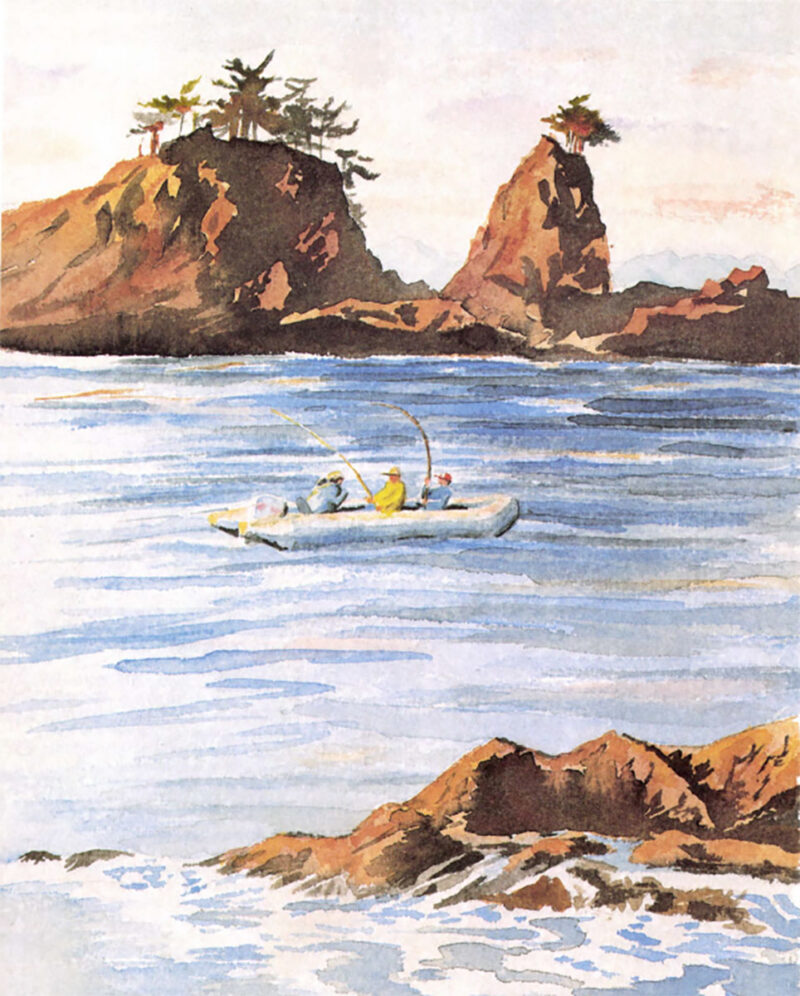

“We’ll be taking big salmon just a short distance from the lodge,” Don predicted. “I mean, in less than five minutes you’ll be in 50-foot water where the kings gather for their spawning run upriver.”

Don’s words brought me back to thoughts of tying into some nice salmon by sundown. Before that I had been engrossed in the rugged beauty of the British Columbia wilderness. The two-hour trip from Seattle to Bamfield, the small fishing village where we would clear customs, is mesmerizing with its fresh, Disney-like colors and contrasts of lush ferns and mosses, craggy rocks of the coastline and emerald green forests of cedar, spruce and fir.

Soon we are banking over the lodge, anchored in a small cove on Tsartus Island, the largest in Barkley Sound. Don had told us to expect a friendly family camaraderie at the lodge and, sure enough, there’s a lively greeting committee on the dock. This is a Wenstob family enterprise and guests are made part of it in minutes. Don exchanges good-natured jibes with Jennifer Wenstob, her son Kevin, and daughters Jessica and Rachel. Jennifer explains that her husband Wayne, an architect in Victoria, won’t join us until the next day. But look. These folks are beginning to get serious about putting our group on salmon. Jennifer has lunch waiting and Kevin and Jessica are piling gear into the boats. We stow our bags in the tight, but comfortable guest room and start getting serious with them.

It’s a little after noon, the sun is warm, the green waters surrounding the dock are pristine and clear. You want to look down there, half expecting to see a knot of salmon cruising through the pilings. Inside the dining room platters of fresh salmon filets, a variety of sandwiches, and Jennifer’s homemade rolls are waiting. A few of the regulars set the tone for our stay by complaining good naturedly (and absolutely without merit) about the food. These folks already feel at home, and you know you aren’t going to be smothered by formality here.

Outside the outboards are chugging quietly. We stuff sandwiches and rolls into our pockets and move to the dock. There I will be four groups. Kevin, Clive Fales, the Wenstob’s cousin Elliott, up from Australia for the summer, and Jessica are the guides. Jessica? Don’t be fooled. This cherub-faced little cheerleader runs a tight ship. She can horse a chinook with the enthusiasm of youth and the endurance of a barrel stave.

We’ll be in Kevin’s boat, and he’s rigged and ready. Don didn’t exaggerate. In five minutes, maybe four, we slow to trolling speed. Kevin has four lines over the side in minutes and the rod tips begin to throb. Heavy bombers take the lures to a depth of 40 feet. The rods are Daiwa 290Es, lightweight nine-footers with plenty of backbone to handle the miniature Mack trucks that cruise the sound. These are whip-action rods, not the broom handles you normally associate with deep-water trolling. And those are fly reels, called “knuckle busters,” at the base of the rods. You know you’ll feel every lunge and headshake.

Although we had looked forward to our trip for weeks, it isn’t easy to concentrate on the rods. A gliding bald eagle targets his approach to a nearby tree; Kevin points to the spot where they saw seals that morning. The cool north woods breeze mixes the scent of spruce and saltwater. Nearby, mountains push through cotton clouds, and the sun massages away the tension of business and big cities.

A screaming reel jolts us back. This is John Jr’s fish, and he scrambles over cushions and tackle boxes to grab the rod. The fish is on solid and a few minutes later, smiles come all around as a king of just over 15 pounds comes to the net. The fish is firm and husky, and has not taken on spawning colors. Several minutes later Don boats a near twin of 18 pounds. We have been on the water for about an hour.

As he reworks the rigs, Kevin talks about the different species of salmon in his waters. We’ll be fishing primarily for chinooks, although coho (silvers)are still running. August is close to the peak period when chinook, coho, and sockeye are most abundant. Chinook production comes mainly from major river systems such as the Fraser and Columbia. Hatcheries scattered throughout BC also release millions of salmon fry each year.

According to Kevin, the largest chinook caught in the area weighed just over 70 pounds. Salmon taken in Barkley Sound have been at sea for three to five years. Farther north, the kings run even larger since they live in the ocean for up to seven years before returning to home streams. The world record, 97pounds, 4 ounces, was taken from Alaska’s Kenai River in 1985.

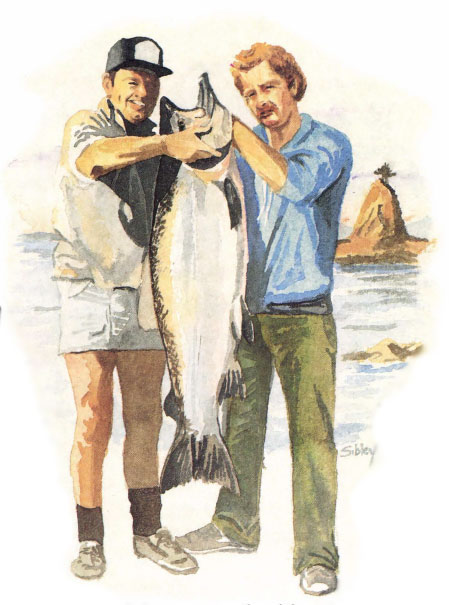

The sun is dipping as the third fish slams our lure. My turn, but I hand the rod to John Jr. My charity is unquestioned as the chinook strips line against John’s furious palming of the reel. Finally the salmon turns, dribbling the rod violently as it fights to move deeper. It’s nearly dark when Kevin slips the net under the weary king, this one just under 20 pounds. Not bad fora few afternoon hours. We’ve heard the whoops from nearby boats and know that others in the group are catching salmon. Back on the dock, flash cameras pop as tired anglers strain to hold their fish at eye level. Kevin and Clive are busy drawing each fish as soon as it is weighed. A cluster of wiry kittens enjoys another salmon dinner in the moonlight.

The daily limit on salmon is four and on this short afternoon, no one has reached it. All boats took fish, however, and spirits are high as the group heads for the showers.

Later, in the dining room, Jennifer, Rachel, and Kevin’s fiancée Sarah Fleming have managed another culinary delight of beef and fresh vegetables with side dishes of broiled-in-butter salmon and halibut filets. Table talk centers around the first “tyee,” with side bets on who will catch it. Tyee is the Indian name for a salmon of 30 pounds or more. No one has come very close to the mark.

The next morning, we learn firsthand about the capricious British Columbia weather. The Wenstobs pass out rubber coveralls and boots as rain pelts the dock. At five o’clock we aren’t ready for a large breakfast. Coffee, juice, cereal, and hot muffins are enough. We’ll return in a few hours for some dedicated work on ham, eggs, and some of the thickest and tastiest fresh blueberry pancakes this side of wherever.

Kevin has the outboard at full speed for only a couple of minutes when we slow for the first trolling pass. As we turn for a second run, we spot Clive’s boat pounding toward us. He throttles down long enough to tell us that his two fishermen have already limited and “you fellows have a nice morning now, you hear?” Kevin takes some ribbing about being late off the dock and we relax, knowing this will be another productive day. In a few hours the sun burns away the low, scudding clouds and we shuck off our rain gear and sweaters. Three fish are in the boat, including my first, and the banter has started over which is the largest. It’s a short discussion, however. My 32-pounder is the first tyee. Now, John Jr. questions my charity of the day before, since the tyee would have been his fish had we followed our rotation. But the day, and the salmon, are enough for all of us. We approach our limits soon after lunch and begin releasing fish under 20 pounds. That evening we learn that a 42-pound king had been taken along with several over 30 pounds.

Kevin has the outboard at full speed for only a couple of minutes when we slow for the first trolling pass. As we turn for a second run, we spot Clive’s boat pounding toward us. He throttles down long enough to tell us that his two fishermen have already limited and “you fellows have a nice morning now, you hear?” Kevin takes some ribbing about being late off the dock and we relax, knowing this will be another productive day. In a few hours the sun burns away the low, scudding clouds and we shuck off our rain gear and sweaters. Three fish are in the boat, including my first, and the banter has started over which is the largest. It’s a short discussion, however. My 32-pounder is the first tyee. Now, John Jr. questions my charity of the day before, since the tyee would have been his fish had we followed our rotation. But the day, and the salmon, are enough for all of us. We approach our limits soon after lunch and begin releasing fish under 20 pounds. That evening we learn that a 42-pound king had been taken along with several over 30 pounds.

Wayne Wenstob drew up his “catch a fish or comeback free” policy with tongue in cheek. John Jr. and I are full-bore professionals at not catching fish. In fact, at one time he was the “not catch fish” champion of three states. We could get nowhere at Canadian King, and nobody in our group came very close either. Later I heard that only one person made it through his stay without landing a salmon and he had fish on several times.

The next day is warm and sunny. Don Toeynan Jr. joins us and we are all catching and releasing fish. As we approach a particularly productive outcropping of rocks, one rod begins to buck. The moment I pick it up, I know that this fish is different.

“What’s the next level up from a tyee?” I grunt, as the salmon starts a reel-searing run in the general direction of Yokahama. I realize too late that the line has stopped paying out and, temporarily corralled, the fish heads topside. Seconds after his dorsal fin breaks the surface, the overstretched line snaps with the report of a rifle, startling the fishermen in a nearby boat. Kevin is, well, disturbed.

“Fifty pounds, John,” he groans. “Probably the biggest king to be hooked around here in weeks.”

Since all the line had been stripped out, I felt vindicated. “There’s nothing I could have done.”

“Well, not exactly,” Kevin is calmer now. “See here. There lovers pooled and the loose line wrapped around one of the handles. Just remember to keep palming the reel. The faster the fish runs, the more pressure you’ll need on the reel to slow him down.”

“Right,” I nodded. ”I’ll remember that the next time I tie into a Sidewinder missile. Just keep the old palm pounding away.”

That afternoon, with our group nearly limited out, we decide to head for open water and a shot at halibut, a saltwater fish that looks like it’s been run over by a flat iron. They’re big as barges here; 70 pounders are not uncommon.

The sea is rough, particularly around the pass joining the sound with open water, and Kevin’s TZAR is tested. Kevin builds his TZARs from aluminum. They are spacious and comfortable when not slamming into six-foot swells. They’re built for stability, like a huge horseshoe-shaped pontoon joined by a flat bottom. I’ve seen pictures of a TZAR hauling a ton-plus generator and it’s hard to imagine anything tipping one over.

The halibut aren’t cooperating, so we cruise offshore, hoping to spot some of the gray whales that frequent the area at this time of year. We get within 20 feet of one that breaches and sounds a few times, then decides he doesn’t like our company.

Back on the sound, we explore a few of the area’s many sea caves; pitch-black inside and dotted with the remains of ancient firesand the bones of unknown early settlers. The shoreline abounds with picturesque sea arches and other scenic jewels worth more than a casual afternoon to examine them.

The weather cooperates again on our final morning. With near limits and sore palms, we enjoy more of the scenery. Jessica and Elliott pass often, making hand signals on the depth and size of their fish. We know when Jessica’s boat is approaching, because she’s usually singing in high spirits and sometimes at full volume. This time Don yells across the water, “Jessica, what did you do with the money your mother gave you for singing lessons?” Her reaction tells us that this is not the first time Don has posed this particular question.

This kind of friendly banter is part of the fun and fills in the few slow moments in fishing action.

Then, too soon, it is over. As the float plane taxis up, the smiles, handshakes, and loaded fish cartons tell you that Canadian King Lodge has a new crop of “regulars,” including John Jr. and myself.

Next time, there’s this 70-pound plus king somewhere this side of Manila.

Veteran saltwater angler and Keys resident Bill Horn shares his years of experience pursuing tarpon, permit, and bonefish and captures the magic and mystery of flats fishing around the world. Not only are biology, behavior, and tactics for the fish covered, but Horn also discusses famous destinations and profiles legendary guides. Guide interviews, fly pattern recommendations, and the latest research round out the instructional information. Buy Now

Veteran saltwater angler and Keys resident Bill Horn shares his years of experience pursuing tarpon, permit, and bonefish and captures the magic and mystery of flats fishing around the world. Not only are biology, behavior, and tactics for the fish covered, but Horn also discusses famous destinations and profiles legendary guides. Guide interviews, fly pattern recommendations, and the latest research round out the instructional information. Buy Now