Men of remarkable talent and courage, Er Shelley and Paul Rainey brought a unique form of hunting to Africa.

As the 20th century dawned, the gamelands near Memphis beckoned two very different young men. One was a pointing dog trainer from rural Michigan, uncannily gifted with animals. The other was a Cleveland-born coal and-coke fortune heir with a thirst for adventure. heir names were Er M. Shelley and Paul J. Rainey.

Paul J. Rainey, a keen adventurer (he once lassoed a polar bear) and expert polo player, donned a British officer’s uniform for this formal portrait.

On a visit in 1900 to the National Bird Dog Championship, Rainey fell in love with the country. He promptly bought 12,000 acres at Cotton Plant, Mississippi and turned it into a sportsman’s paradise. He expanded a rustic lodge to a dozen bedrooms, anchored by a trophy room and an indoor pool on the ends. He built a 50-stall brick polo barn, kennels for hounds, bird dogs, retrievers and fighting dogs, fishing lakes and a village of servants’ homes. He installed a rail siding for private cars. At nearby New Albany, he built a world-class hotel, complete with marble floors and a European chef. He called his place Tippah Lodge. On Saturday nights, the music of W.C. Handy’s jazz band from Memphis drifted over its dance floors.

Rainey followed the neighbor Hobart Ames and raised Black Poll and Jersey show cattle and Duroc swine. Addicted to riding to the hounds, he served as president of the American Foxhound Association and hosted its National Hunt. Standing six-feet-four-inches, he cut a handsome figure on the Memphis social scene as well as on Long Island, where he maintained a mansion, racing stable and ocean racing yacht, and in England at his lavish country house. He also owned a 23,000-acre duck-hunting marsh in Louisiana.

A 10-goaler in polo, Rainey rode for the Meadowbrook Club, the first team to defeat the British. He brought a polo team to Cotton Plant to represent the South. He raced automobiles. He patronized the Bronx Zoo and the American Museum of Natural History. On Harry Whitney’s Arctic Expedition of 1910, he lassoed and helped capture a polar bear — the great Silver King — which would long delight children at the zoo. After his death, his sister gave the Bronx Zoo its landmark art deco gates in his honor and donated his duck marsh to the Audubon Society. Its natural gas reserves still finance Audubon projects.

Er M. Shelley would become a revered figure in the world of pointing dogs.

The dog trainer Shelley, born in 1874, had won his first pointing dog field trial in 1898. In 1906, he capstoned that career by winning the National Bird Dog Championship with the setter Pioneer. At the same time, he had in his string the famous setter Jessie Rodneld’s Count Gladstone and pointer Hard Cash. A photo of the three dogs together is today the most recognized photo of bird dogs ever made. Soon after Shelley’s win of the national, Rainey hired Shelley as his dog trainer and huntsman. Thus began a unique sporting collaboration.

In the fall of 1910, Rainey, restless for adventure, hit on a radical plan: to hunt lions in Africa with hounds. It had never been tried. Knowledgeable hunters scoffed. He’d never get the dogs true to lion scent because of so much other game, and if he did, they’d be mauled by the big cats. Rainey looked to Shelley to solve these problems.

In January1911, Shelley sailed to British East Africa. He camped at the Nairobi racetrack, which he acquired with Rainey’s money. For hunting mounts, he bought all the placed thoroughbreds at a point-to-point race meet, 30 in all. On the plains outside Nairobi, Shelley trained the hounds with the help of George Outram, a young Australian and one of the first four professional hunters for Newlin and Tarlton, the pioneer safari outfitters.

To get the hounds true, Shelley bought a pair of lion cubs. Each day the cubs were led across the plains, and their course marked with flagged canes. Riding thoroughbreds with bullwhips in hand, Shelley and two assistants whipped in any errant hound. In no time, the pack hunted true.

In the meantime, the more than 30 bear hounds and fighting dogs Rainey had obtained from J.M. Avent of Tennessee had been augmented by four sight-chasing staghounds, 20 “green” Mississippi hounds, eight shepherds from Illinois, six English fox terriers, six police dogs from Germany, six quarter-bred English fox hounds, some local airedales and finally several feral pie dog-airedale crosses Shelley trapped near Nairobi.

When Paul Rainey and pals arrived, all the dogs were assembled and trained. Rainey hired Alan Black as head professional hunter. Shelley described Black as “probably the best in the country.” But Black was not enthusiastic about hunting lions with dogs, fearing someone would get hurt and mar his professional reputation.

The 320-mile railroad from the port city of Mombasa to Nairobi had been completed just 10 years earlier. Teddy Roosevelt had been in the country for his celebrated safari the year before. Nairobi was a tiny outpost with few European residents. While Victorian adventurers and Indian traders were being drawn to the Dark Continent, Nairobi was still primitive. Game was everywhere — Shelley saw 30,000 head on his train ride to Nairobi.

Lions were still classed as vermin, requiring no hunting license and carrying no limit. Railroad workers and farm hands lived in terror of man-eaters, which had killed hundreds during the railroad’s construction and now regularly ambushed maintenance crews.

Though they would hunt near the equator, the high altitudes, between 6,000 and 12,000 feet, meant cool mornings and evenings. But midday sunstrokes could quickly kill a hatless white man. While hunting lions with dogs was untried, “riding lions” – hunting them from horseback — was not.

“The expedition for this first hunt was enormous – one of the largest safaris that ever left [Nairobi] … over 200 porters and three large ox wagons that carried five tons each … The white men … were … Rainey, Dr. Johnson, Mr. Heller of the Smithsonian … a movie picture operator and the white hunters, Black, …Outram and I,” wrote Shelley in his 1924 book, Hunting Big Game With Dogs In Africa.

On the first day’s hunt, 150 porters lined up as game drivers. The guns, or hunters, were mounted on steeplechasers. The first day brought several close calls for Shelley as he learned not to ride close to the trailing hounds, for in tall grass the lions would drop back and lie in wait for a rider.

“We bagged nine lions that day and several of the Masai chiefs … When they saw nine of their worst enemies lying upon the ground … sent Mr. Rainey two fat sheep and called him “bonner encuba” (meaning the great master) … We bagged 27 lions on this trip of six weeks,” Shelley wrote.

Paul Rainey had promised the American Museum of Natural History a group of lion mounts for its central exhibit. Once the hunting techniques had been perfected, Shelley and Rainey set out to fulfill the promise. For this second hunt, they traveled to the holdings of Rainey’s friend Lord Delamere, a pioneer elephant hunter and settler, near Lake Elementeitia. On the first night in camp, a monster lion roamed nearby.

“We could hear him roar occasionally and grunt with that deep, sonorous never-to-be-forgotten rumble, as he passed along … There was no more sleep that night, since try for him we must.

“Mr. Rainey and I started early, taking some 15 or 18 hounds, while the boys led as many fighting dogs behind … Jim and Buster, two very reliable strike dogs, were allowed to cast about, while the remainder of the [hound] pack was kept at heel.”

Buster soon struck, then “The entire pack was with him, harking in. What a riot of voices! What pandemonium! … We had a good, stiff gallop for about eight miles to the foothills of a mountain … The boys with the fighting dogs [on leash] were a mile or two behind. “At last, the lion jumped from his lair …

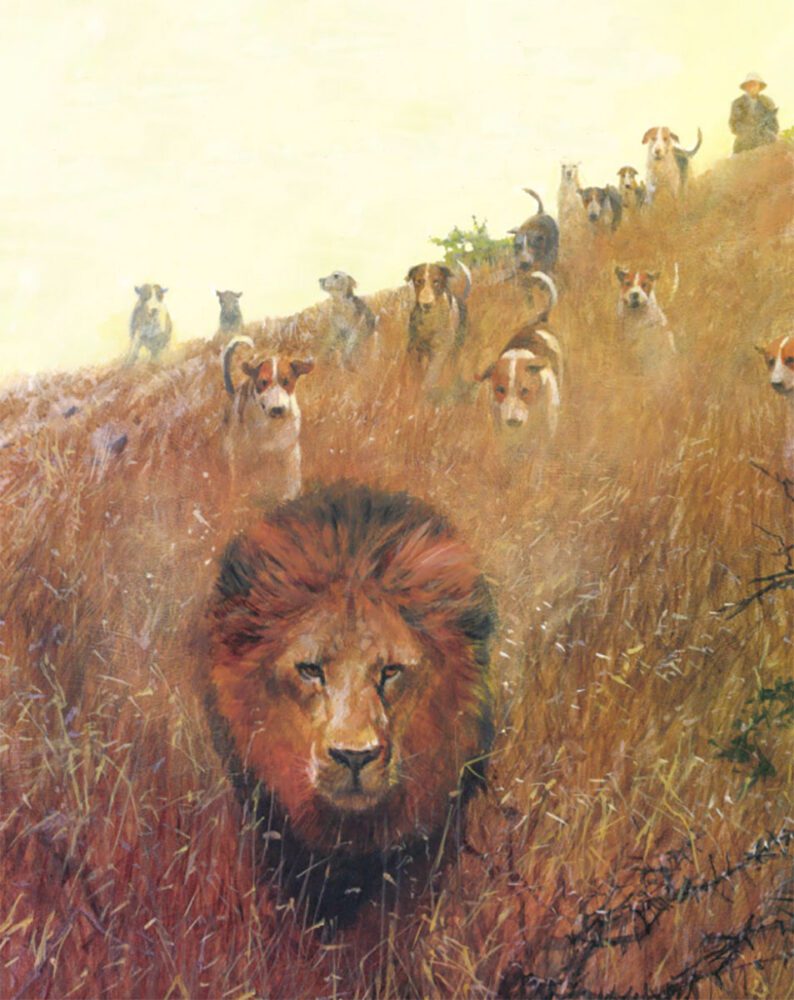

Hounded (detail) – by John Seerey-Lester

“Mr. Rainey rode on toward the pack, while I had the boys release the fighters, their voices varying from high crescendo to deep bass and mingling with the general din … He [the lion] saw us, and broke through the dogs, making straight for us. Mr. Rainey took the first shot as the maddened beast came plunging through the high grass, but this did not stop him. On he came roaring and lashing his tail, all the fury within his untamed breast being wrought up to its highest pitch. It was my turn then, and I fired, knocking him down in his tracks. Mr. Rainey’s bullet had pierced the fleshy part of the forearm, while mine had crashed through his brain. He was by far the largest lion that we had ever killed …a new record for that country. This one measured 10 feet and 10 inches. He stood 50inches at the shoulder, and measured 38inches around his forearm.”

Er Shelley had just saved his employer’s life. It would not be the last time. The next day, a seven-mile hound chase led to the same mountain where the big lion had been killed, and again Shelley and Rainey faced a charge. This time they dropped the lion at their feet with shots to the head. An old Masai warrior tending cattle had seen them pass on horseback and joined the hunt with his spear. After the lion charged, they looked about for him, and suddenly a spear struck in the ground beside them. The old warrior was 40 feet above them in a tree! Soon they harvested the rest of the “Rainey Group,” nine lions that for many years stood mounted in the entrance hall of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

While Rainey made a brief return to America, Shelley and the dog pack were recruited to search for a man-eating lion. Horses could not be used because of tsetse flies. Shelley took a dozen hounds and a young American, Roy Stewart, also employed by Rainey, by train to Simba Station. From there, the dogs succeeded in running the man-eater into hilly country where Shelley killed it with a fantastic running shot of 475 yards with open sights (using a .350 Rigby Mauser). Then a pride of 10 lions was spotted, including a huge black-maned specimen. Shelley killed it with an unbelievable shot of 710 after several of Nairobi’s top white hunters, who were closer, missed it repeatedly. On this trip, Shelley contracted a high fever and became delirious, though later a doctor in Nairobi cured him and he remained healthy his remaining four years in Africa.

The publicity created by the new Sport of lion hunting with dogs left the budding safari industry concerned that Rainey and Shelley were having too much success. At the same time, farmers near the Southern Game Reserve were complaining to the government that lions from the Reserve were playing havoc with their livestock. To address the problem, the government invited Rainey and his friend, Dr. Johnson of Lexington, Kentucky, and white hunters Harold Hill, Roy Stewart and Shelley. They were joined by Captain Murray and his famous white hunter Percival (who had guided Teddy Roosevelt and would later guide Ernest Hemingway) and the chief game ranger, Ousman, with his own safari. Over a hundred porters, 16 pack mules, an 18-ox wagon and a six-mule dog dray supported the expedition.

For two weeks the action was fast and furious, and another record for lion kills was posted. Not long after, lion and leopard hunting with dogs would be outlawed as too lethal.

In the summer of 1914, Shelley took a leave of absence from Rainey’s employ. After a brief visit back to America, he returned to Africa for two more years on his own, hunting and making motion pictures.

In his book, Shelley does not mention a dark chapter for Rainey after Shelley temporarily left his employ. At the Long Bar of the Norfolk Hotel in Nairobi, the gathering place of white hunters and their well-heeled safari clients, Rainey recruited professional photographer Pop Blinks as camera man for his new compressed air-driven camera. Rainey then sought a white hunter to set up a scene in which a lion charges a camera. Alan Black, George Outram and the cousins Clifford and Harold Hill all turned Rainey down, judging the job too dangerous. That left Fritz Schindelar, a dashing, mysterious character, perhaps a Hungarian Hussars commander on the lamb from a European scandal. He was known as absolutely fearless in the face of dangerous game, as was Rainey.

Rainey had already achieved success with silent documentary films, including Water Hole, African Hunt, Common Beasts of Africa and Military Drill of Kikuyar Tribes and Other Native Ceremonies.

African Hunt had run for a year-and-a-half at Broadway movie houses. But Rainey wanted above all else to film a charging lion close up, and Fritz Schindelar agreed, for high pay, to set it up. The party traveled to Rainey’s Naivasha ranch, 80 miles west of Nairobi. Being a region of ranching and thus lion policing, the big cats were educated to hunting and doubly dangerous.

Schindelar cut a daring figure on his white Arabian polo pony. In their first 15 days, the party killed eleven lions. On the 16th day, January 9, 1914, the party camped southeast of Lake Naivaska in rough country covered with black volcanic rubble. At Ngasawa Gorge, the hounds jumped a “huge and very alert maned lion.” The chase was on.

The lion struck out up Mount Longonat, a 9,000-foot extinct volcano, seeking the cover of high leleshwa brush. Soon the dogs bayed it. The heavy cameras were set up on tripods, and now it fell to Schindelar to induce the lion to charge. He repeatedly rode his white pony to the edge of the brush, but the lion would not take the bait.

Then Schindelar rode in deeper from another angle, and the lion charged. The charge bowled the pony over and knocked Schindelar out of the saddle. He landed on his feet with his double rifle in his hands. The lion charged him, and he fired both barrels into its open jaws. The shots had no effect, and the lion tore into Schindelar’s stomach. He died two days later in the Nairobi hospital.

A pall was thus cast over the Rainey African experience, but Shelley, no longer in Rainey’s employ, chose not to tell of it in his book. A full account of the incident is included in White Hunters by Brian Herne (Henry Holt & Co.,1999), an excellent history of safari hunting in Africa.

World War I temporarily ended Rainey’s African adventures. For health reasons, Rainey was rejected for U.S. military service, but he was determined to serve. He went to England and arranged to sponsor, at his own expense, an ambulance unit in France under his command. He also served as a photographer for the Red Cross. His portrait in a tailored British officer’s uniform hangs today in the dining room of the lodge at The Rainey Place, a part of the original Tippah Lodge property, now owned by H.L. “Sandy” Williams and John Vaughan IV, of Corinth, Mississippi. The partners have spared no effort to restore it as a wild quail paradise, using habitat practices recommended by game biologist Dr. Wes Burger of Mississippi State. Rainey and Shelley would no doubt be pleased.

A decade after Rainey’s death, Ernest Hemingway made a safari in the same region. He wrote up the experience in The Green Hills of Africa, judged by the critics as one of his poorer literary efforts. But the trip inspired two of his three greatest short works of fiction — The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber (any hunter’s favorite) and The Snows of Kilimanjaro. The third was The Old Man and the Sea, which won him the Nobel Prize in 1954.

The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber is based on a real hunt on which a husband died, accidentally or on purpose, shot by his wife as a wounded buffalo charged. It became the 1947 motion picture The Macomber Affair, starring Gregory Peck, Robert Preston, Joan Bennett, Reginald Denny, Carl Harbord and Gean Gillie. This picture sparked the post-World War II revival of the safari business, and the worldwide awakening to the need for African wildlife conservation. It also led to a series of additional Africa adventure films, including King Solomon’s Mines, The Snows of Kilimanjaro and Mogambo.

Lion at Bay (detail) – by John Seerey-Lester

Shelley privately published his book on his Africa experiences in1924, a year after Rainey’s mysterious death at sea while crossing from America to his holdings in British East Africa (he was 46). Rainey had studiously avoided matrimony, but not female company. Shortly after moving to Tippah Lodge, he met May Peters Graham, wife of a prominent Memphis physician. When the doctor threw her over in favor of a maid, Mrs. Graham moved to Tippah Lodge and became Rainey’s hostess. She and his sister, Grace Rainey Rogers, were with him on the ship when he died. Mrs. Graham lived on part of the Tippah Lodge property given or sold to her by Rainey’s sister until her death in 1959.

While the cause of his death has never been revealed, legend has it he was hexed by a fellow passenger from Asia who had provoked Rainey by being too friendly with Mrs. Graham. The man supposedly said, “You will be dead by your next birthday,” to which Rainey replied, “Not likely — tomorrow s my birthday.” Rainey died on that46th birthday, perhaps from a stroke or cerebral hemorrhage.

Shelley’s book reveals Rainey as a man of remarkable talent and courage and a man deeply respectful of the East African culture and peoples. Shelley learned Swahili soon after his arrival there. He marveled at the ability of native porters to trek15 miles a day carrying 60pounds of gear on their heads. He was in awe of the courage and teamwork of native hunters who in small groups, armed only with shields and spears, faced lions and slew them with seeming ease.

In addition to his Africa book, Shelley published two influential books on dog training, Twentieth Century Bird Dog Training and Bird Dog Training Today and Tomorrow. He pioneered the use of pigeons and the “chain gang” method of teaching dogs by encouraging them to observe others in training. He developed humane methods for curing gunshyness still used today. According to fellow Field-Trial Hall of Famer Ed Mack Farrior, he was the most interesting conversationalist Farrior ever knew.

After 14 years as Rainey’s huntsman, Shelley spent the rest of his life as a bird dog trainer, managing hunting reserves in Alabama, South Carolina and Illinois, and finally settling in Columbus, Mississippi, where into his 80s he maintained his own well-patronized training establishment. Several of the most successful bird dog trainers of the 20th Century were mentored by Shelley, including J. Louis Holloway, Clyde Morton and Al Brennaman. Shelley died in 1959 at age 85, a revered figure in the bird dog world, as well as a legendary African professional big-game hunter and accomplished writer.

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now