Tour featuring major retrospective of Wyoming’s Tucker Smith ends January 2, 2022.

One enduring memory I have is of a silhouetted figure, the outline of a cowboy hat, the rangy gesture of a man, hand extended, holding what appeared to be a magic wand, reaching toward a small square surface tilted upright on an easel.

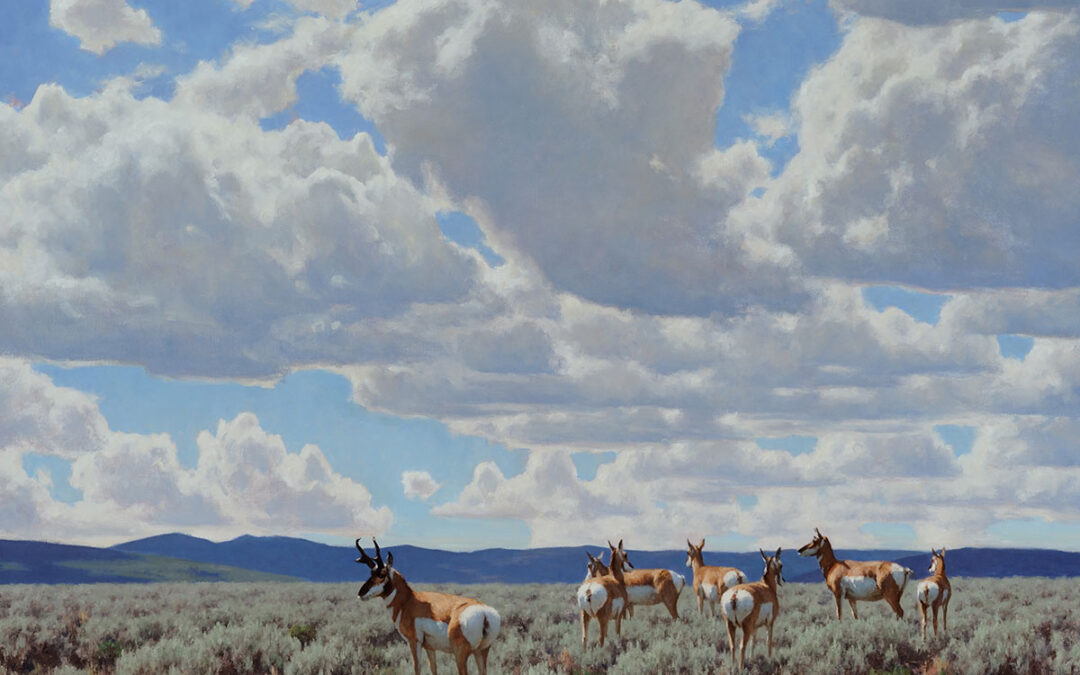

Tucker Smith (American, b. 1940), The Boys of Summer, 2018. Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, U.S.A., museum purchase in honor of Margaret Webster “Maggie” Scarlett, with thanks for her many years of service as Chair of the Whitney Western Art Museum Advisory Board. © Tucker Smith.

Steadily, as clouds churned overhead, as the sun sent gentle streaks of afternoon light gleaming across the blue–green surface of Peak Lake, the actual place began to take shape. He had heard bull elk bugling there in the fall, seen tracks left by recolonizing grizzlies, observed moose in the drainages spiraling downward from Vista Pass through the headwaters of the Upper Green River and encountered herds of pronghorn on the flats nearly a mile below.

How do you conjure the spirit of a mountain range, in this case the Wind Rivers of Wyoming, and not diminish their power?

Always, translation comes down to the perceptive abilities of the beholder. Each of us goes afield and accrues memories, so vivid in the mind they can make us cry in hindsight. And yet, if pressed to explain the feelings in words, it’s nearly impossible. Unless, of course, one is a painter, and when you are a damned fine wielder of brush and oils, a single person can bring the ineffable story of an entire wild rise of rock to life. In this case, Tucker Smith has more than earned the title “painter of the Winds” which is no small appellation.

For any artist it takes pluck—some would even say, blind arrogance—to claim one “walks in the footsteps of a master.” Carl Rungius (1869-1959) is considered nonpareil when it comes to painting North American big game animals. Countless wildlife and sporting artists claim they are inspired by him.

Yet when people assert that Smith has wandered up the same paths as Rungius to achieve a more airy perspective on wild backcountry, they don’t mean it figuratively or casually. He literally has spent decades tracing the same routes Rungius went on horseback at the start of his career when, as a young man recently arrived from Germany in the late 19th century, he ventured into the Wind Rivers.

For Rungius these Wyoming treks, while formative and earning acclaim in the effete fine art world of the East, proved to be short lived. He not long afterward decamped to Banff in the Canadian Rockies and divided his time between there and New York City for half a century. Smith hasn’t courted the Winds as a visitor, nor does he aspire to “paint like Rungius.” He’s built a venerable body of work painting wildlife, breathtaking landscapes, cowboy camps and hunting outfitter scenes as a way of solidifying his connection to home.

Tucker Smith (American, b. 1940), East Fork Rams, 2011. Oil on canvas, 24 × 32 in. Collection of Jerry and Viesia Kirk. © Tucker Smith.

Last summer (2020), the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole staged the largest and most important retrospective of his career, Tucker Smith: A Celebration of Nature. What a showing it was—and is—the artist’s remarkable corpus hanging in a gallery space that in years past has, fittingly, featured the second largest public collection of Rungius works in the world. Some 75 finished paintings plus 15 field studies assembled in a single grouping that next travels to museums in Oklahoma, Virginia and Georgia.

Yes, in earlier decades, it would have been accurate to say that Smith haunted Rungius’ shadows but this exhibition demonstrated that Smith, in his own right, is one of the most important Western painters of his generation.

Smith does not like to attract attention to himself. Born in 1940 in St. Paul, Minnesota, his family, in the dawn of his teenage years, relocated to Pinedale in a fateful move that has had positive ripple effects in the art world. Smith grew up knowing the same outfitting family that had taken Rungius on his first painting trips into the Winds.

I have a stack of notepads filled with observations about Smith made over the years, dating to when he worked in Helena, Montana, as a computer program and systems analyst for the state of Montana. It may seem a disconnect to point out that Smith earned a degree in mathematics, not fine art, from the University of Wyoming, yet it makes perfect sense when examining the complicated relationships between color value and harmony present in his compositions.

Back in the days when I first interviewed Smith, he had gained some acclaim painting in his free time creating railroad scenes. With a house in the outskirts of Montana’s capital city, he and his wife, Jean, grew homesick for the western front of the Winds that stretch north and south of Pinedale where they had been high school sweethearts.

The Smiths made a big move, Jean encouraging Tucker to follow his bliss. Heading home to Wyoming proved to be transformational, unlocking talent that had only been hinted at when he held down a job to pay the bills and raise a family.

A generation ago, I had the good fortune of joining Smith on one of his “artist painting trips” high into the Wind Rivers put together by big game hunting guide Todd Stevie of Thomson Outfitters. Joining Smith then were painters Jim Morgan and Christopher Blossom and over the years other landscape and wildlife artists—a veritable who’s who—have gone on the Vista Pass ascent, as much to share company with Smith as to for themselves. It is the source of a dazzling diversity of works that reflect the contemporary West, not over the over-romanticized version of it.

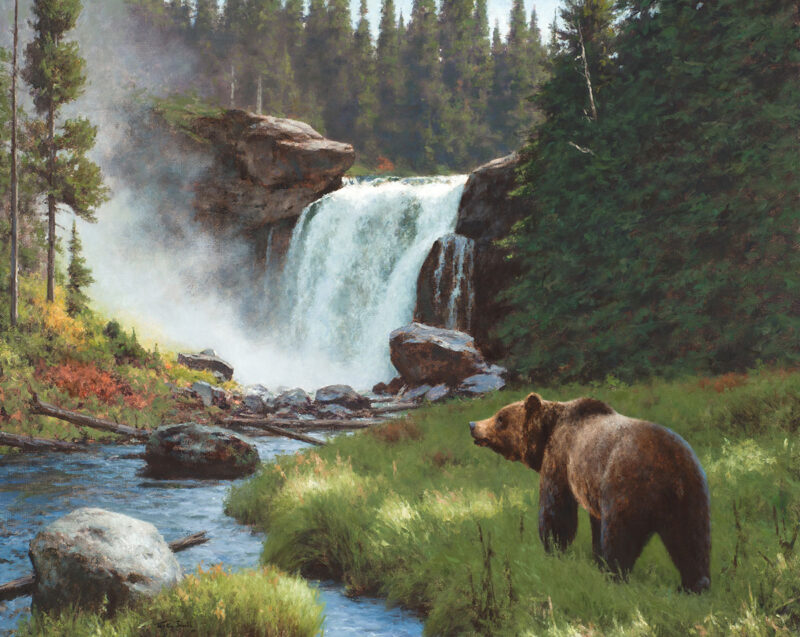

Tucker Smith (American, b. 1940), Moose Falls, Yellowstone National Park, 2014. Oil on canvas. 32 × 40 inches. Purchased with additional funding generously provided by the Friends of Jean and Tucker Smith, National Museum of Wildlife Art. © Tucker Smith.

“This is the place that has always filled him up,” Morgan told me as we camped with Smith years ago. “It’s a special treat to be in the Winds with Tucker as your guide,” added Blossom. “The adage is that your strongest work happens when you paint what you know. When you see Tucker’s portrayals of scenes in the Northern Rockies, there’s no question that he knows his subjects and wants to present them in a way that gives them honor,” suggested painter Matt Smith (no relation) in a profile I wrote about Tucker.

Dr. Tammi Hanawalt, curator at the National Museum of Wildlife Art, says the exhibition chronicles Smith’s evolution and she points to a work such as “Moose Falls, Yellowstone National Park” as an example of his ability to paint realistically, with detail, that is actually a mesmerizing convergence of abstract brushstrokes.

No living painter has done more to champion Rungius’ connection to Wyoming. Hanawalt, too, has accompanied Smith to the Winds. “He can point out in the Rungius catalog everywhere he painted in the Winds down to the old trees that were growing when Rungius passed by them,” she says. “Tucker is showing us landscapes as they were known to people who came before us and as they still exist today. He’s been there as a witness to a part of the United States that holds a lot of meaning, especially for those who know Wyoming.”

Rungius was a big game hunter who used the animals he harvested to inform his understanding of musculature and anatomy. Smith is a sportsman who has spent thousands of hours observing his subjects in all seasons, commemorating the giants for all to share.

Among the scenes that have earned Smith accolades or command popular attention are two that are not based in the Wind Rivers. “Return to Summer” depicts a bison herd along the Rocky Mountain Front of Montana, along an ancient corridor known as the Old North Trail where wildlife and indigenous people moved southward down the continent. The painting won the 1990 Prix de West Invitational Purchase Award from the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City—the most prestigious prize in Western art.

Since then he’s earned numerous other kinds of recognition from premiere museums across the West. Another work, “The Refuge,” is a panoramic showing thousands of wapiti that mass every winter at the National Elk Refuge in Jackson Hole. The refuge is located just across the highway from the National Museum of Wildlife Art and the Smith piece made its debut on the morning that the museum opened. As a gesture of honor, the museum prominently displays it at the main gallery entrance.

Tucker Smith (American, b. 1940), The Refuge, 1994. Oil on canvas 36 x 120 inches. JKM Collection, National Museum of Wildlife Art. © 1994 courtesy of The Greenwich Workshop.

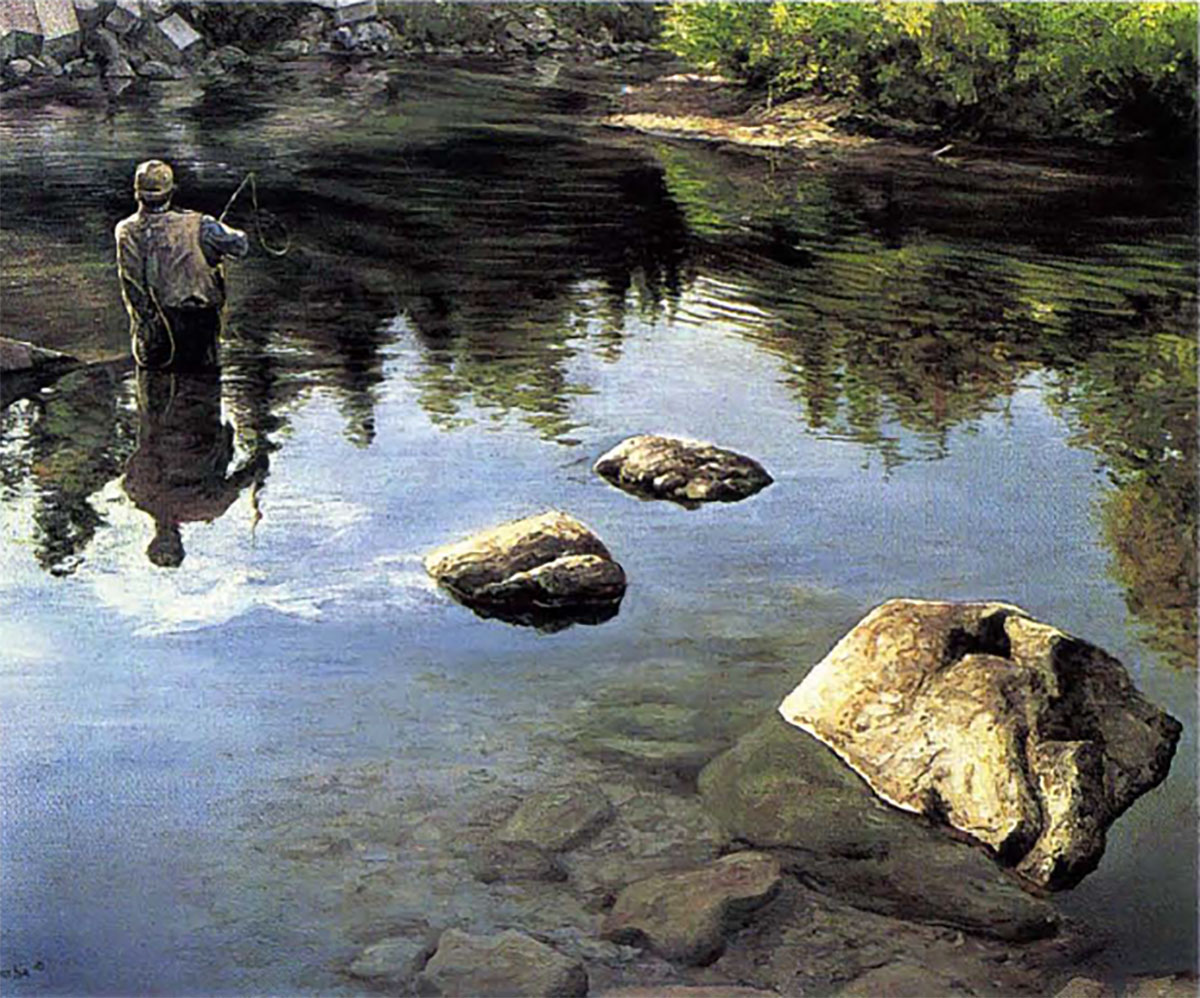

While Smith’s finished paintings have been in demand, becoming part of private and public collections, what has also resonated with me are his plein air pieces and field studies painted spontaneously in the mountains. Beneath shifting ambient light and dramatic backdrops ranging from glacier sheathed peaks to glistening aquamarine tarns that sparkle like jewels, they are beauties. Known for being eminently affable yet laconic in personality, Smith, to me, always reveals his passionate side in the plein air pieces. They project an immediacy and a daring—as if he is openly declaring an affection for place that originates deep in the soul.

As he has said, “it’s much more difficult to paint loosely than to paint tight” and indeed his maturation is evident in how far he’s come from those early railroad scenes long ago.

“Some think that to be creative one must invent the new. However, to be obsessed with rebelling against the established can inhibit creative observation, just as thoughtlessly adhering to the established inhibits creativity,” Smith says. “Personally, art has broadened my interests and helped me to see the not-so-obvious. One of the greatest attributes of art is that one does not need to be a painter or sculptor to participate. One only needs to observe.”

If you want to see some of the finest wildlife art of our time, it is well worth your while to see the exhibition.

You can still catch the exhibition, Tucker Smith—A Celebration of Nature, until January 2, 2022 at the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, GA.

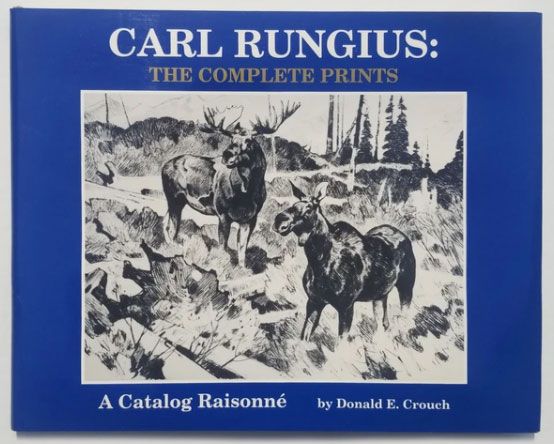

Hardcover, 210 pages. By Donald E. Crouch, 1989. Extra large format. A comprehensive study of print compositions created by American wildlife artist Carl Rungius (1869-1959). Includes the most thorough bibliography on Rungius (up to 1989), along with information on periods in his printmaking, print editions, themes, prices, condition of the copper plates today, and museum holdings. The 46 etching-drypoints are reproduced to exact scale, with the exception of three vertical compositions, and are accompanied by 91 drawings, photographs and documents, and five paintings reproduced in full color. Buy Now

Hardcover, 210 pages. By Donald E. Crouch, 1989. Extra large format. A comprehensive study of print compositions created by American wildlife artist Carl Rungius (1869-1959). Includes the most thorough bibliography on Rungius (up to 1989), along with information on periods in his printmaking, print editions, themes, prices, condition of the copper plates today, and museum holdings. The 46 etching-drypoints are reproduced to exact scale, with the exception of three vertical compositions, and are accompanied by 91 drawings, photographs and documents, and five paintings reproduced in full color. Buy Now