Oysterman and artist, Gilbert Maggioni, married late and had no children. He passed his legacy to two young men, William Rhett of Beaufort and Grainger McKoy of Sumter.

Gilbert Maggioni was an ornery old cuss most people said. He cussed the weather and he cussed the tides and he cussed the moon and the wind and he cussed his oyster pickers and his shuckers whom he dearly loved and he casually shot at trespassers.

His granddaddy immigrated from Italy in 1870, took a wife in Jacksonville and got into the oyster business in Thunderbolt, Georgia, so named from a lightning strike that made a flowing well; nasty water everybody said, overwhelming even the kick of local scrap-iron whiskey, a considerable accomplishment.

Some stuff is just too good to ever make up.

***

There was a Maggioni cannery with a steam boiler in my hometown and I marked my childhood with the throaty blasts of the whistle. When it summoned the shuckers to work, it was time for school. Noon blast, the school ate lunch, an hour later, another blast, we got back to the books. And finally, the knock-off whistle when Momma put supper on the table, oysters and shrimp most times.

You could hear that whistle for miles.

***

“It’s a brave man who first ate an oyster.” That’s attributed to Johnathan Swift, the author of Gulliver’s Travels, and it’s a lie. It was a hungry man who first ate one. Early coastal humans watched the ’coons and the birds. “Maybe we should get us some of those? At least we won’t have to chase ’em.”

They did and the shorelines hereabouts are littered with ancient shell piles from those first oystermen.

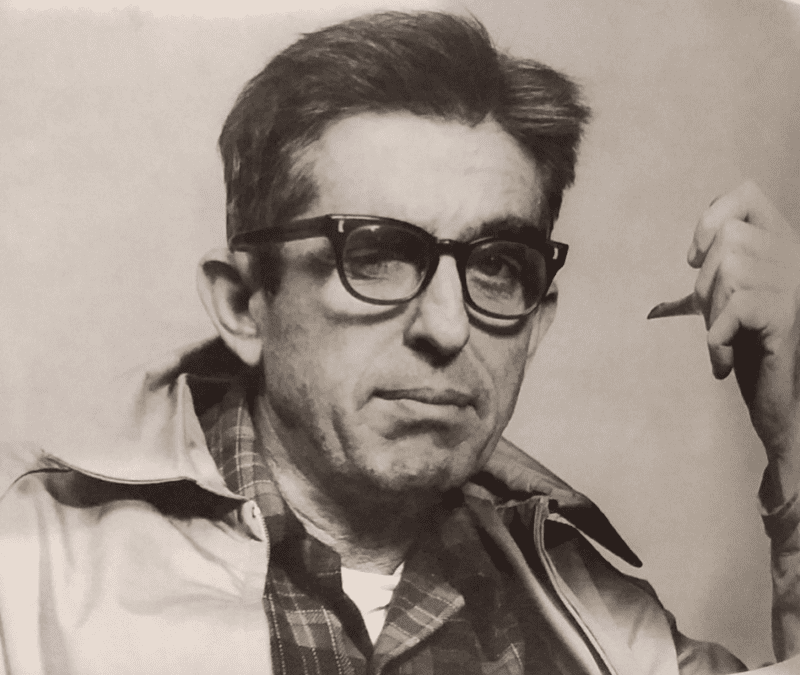

Gilbert Maggioni

Fast forward ten-thousand-odd years. In 1887, a U.S. government report described how New Yorkers went wild over “oysters picked, stewed, baked, roasted, fried and scalloped; oysters made into soups, patties and puddings; oysters with condiments and without condiments; oysters for breakfast, dinner, supper; oysters without stint or limit, fresh as the pure air and almost as abundant.”

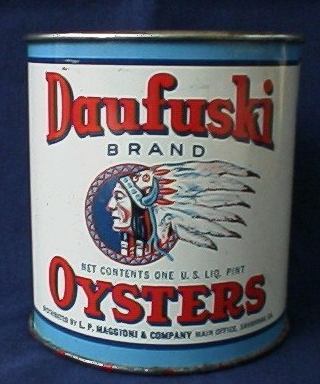

“Almost” is a mighty big word. When northern and Chesapeake Bay oyster banks were over-harvested, oystering moved south. The L. P. Maggioni & Company established its first cannery on Daufuskie Island in 1893, and eventually built five more hereabouts. Fall and winter, black rivermen went out in flat-bottomed boats powered by oars or sail every low tide, tonging up fifty to one hundred bushels per man per day. At about ninety pounds per bushel, it was literally backbreaking work, and empty opium vials—sold over the counter or ordered from Sears and Roebuck—still turn up along creekbanks to this day.

The men hauled oysters to the factories, where their wives and sometimes their children worked long hours in the shucking sheds. Five gallons per person per day was considered a tolerable output. Each gallon was worth a bronze token the size of a half dollar, redeemable for cash on Friday, or when money was tight, as it often was, tokens could be swapped for grits, flour, bacon and beans at the company store.

Maggioni’s “Daufuski” brand oysters with the distinctive Indian chief label were shipped world-wide, reportedly even enjoyed by Tsar Nicolas II of Russia.

Gilbert Maggioni bragged up a typical oyster-picker in a 1977 interview. “He lived probably not far from the creek…winter time he would gather oysters for one of the oyster plants and in the summer time he farmed…He was spindle-legged but about three feet across at the shoulders, and he could break store-boat oars just as fast as you handed them to him…It was not an uncommon thing for one of these gentlemen to row from Bluffton to Beaufort, 22 miles, to buy groceries.”

Gilbert Maggioni bragged up a typical oyster-picker in a 1977 interview. “He lived probably not far from the creek…winter time he would gather oysters for one of the oyster plants and in the summer time he farmed…He was spindle-legged but about three feet across at the shoulders, and he could break store-boat oars just as fast as you handed them to him…It was not an uncommon thing for one of these gentlemen to row from Bluffton to Beaufort, 22 miles, to buy groceries.”

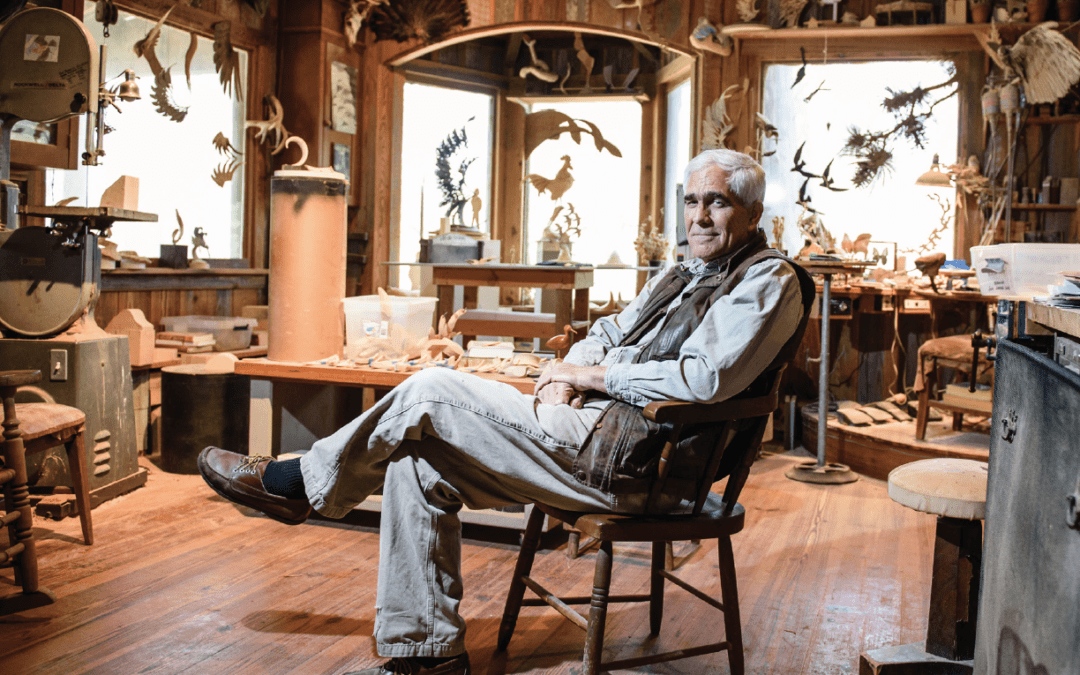

Overharvesting and pollution took their toll. One by one the canneries closed though large scale live-shucking operations continued well into the 1970s, oysters shipped out iced down and raw. Gilbert Maggioni, who had been painting since the late 1930s, had more time to devote to his art. He was a bachelor most of his life, “and only had to bush-hog his yard once a year,” one man recalled. Another remembers a shed full of wood chips and half-carved decoys, not far behind the shucking house. “His birds were expensive, even in those days. I still wish I would have bought some. Thankfully he did not recognize me as one of the boys he shot at earlier.”

Gilbert Maggioni married late and had no children. He passed his legacy to two young men, William Rhett of Beaufort and Grainger McKoy of Sumter. Both had college degrees but that did not matter. He set them to work in the oyster factory—without pay—and after ten to twelve grueling hours, he would consent to letting them look over his shoulder. “Be true to the bird, be true to the bird,” was his oft repeated mantra.

And what a truth! By then Maggioni had gone far beyond working decoys. He was creating sculptures of wood that resembled taxidermy more than carving. Feathers—sometimes a hundred or more—were individually carved and inserted into the body of the bird—or birds as was often the case. And they were not just gamebirds anymore, but coots, gallinules, herons and hawks. And Maggioni introduced a new technique, high-tensile steel wires hidden within his birds so they appeared actually in flight. Imagine two red tail hawks fighting over a copperhead snake, one hawk on his back on the ground, another in flight and the copperhead stretched writhing between them. You can’t see the steel wire running from the grounded hawk, up through the body of the snake, to the beak of the top bird which is firmly latched onto the snake’s neck.

The results appear to defy gravity.

“Covey Rise,” 1981, by Grainger McKoy.

COLLECTION OF EARL F. SLICK.

PHOTO COURTESY OF GRAINGER McKOY.

Both Rhett and McKoy adapted and refined the technique and both have become acclaimed artists in their own right. Rhett owns a gallery on Bay Street in Beaufort, South Carolina, where he displays and sells his own carvings, Lowcountry-themed historic maps, prints, even antique firearms, two floors of delight for any antiquarian. McKoy has expanded into a line of jewelry managed by his son, gamebird brooches, feathered rings, pendants in gold and silver. “I wanted something that would sell when I wasn’t working,” he explained.

Indeed, an artist can only do so much.

Gilbert Maggioni passed in March of 2001. I saw him toward the end. He was holed up in his creekside home, oyster beds visible through a picture window, his working decoys on shelves and hearth. There was a fire in that hearth, oxygen mask be damned. He’d strip off his mask, tell stories and laugh ’til his scant breath failed him. Then he’d take a few whiffs and begin again.

He’s buried in Savannah, not far from Thunderbolt where this story all began.

Only six people showed up for the funeral. He was an ornery old cuss, like I said.

Had I known, there’d been seven.

For more information: The Rhett Gallery 901 Bay Street, Beaufort, SC 29902 (843) 524-3339 www.rhettgallery.com. For links to Grainger McKoy’s jewelry page, visit www.grangermccoy.com.

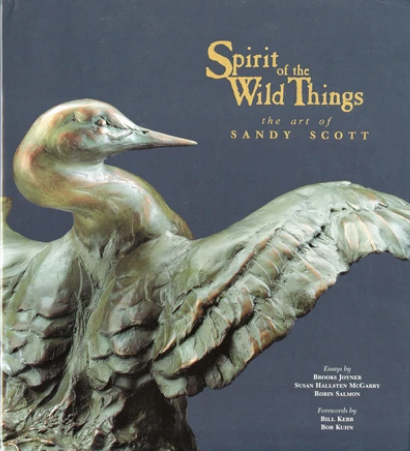

Sandy Scott is widely recognized as one of the country’s premier animal sculptors and printmakers. Designed with highest possible standards, including a wealth of specially commissioned color plates and black-and-white photos, this book is meant to be savored and cherished. At its heart are Scott’s own thoughts and musings, compiled in her journals over the years. Organized into four chapters titled Seeing, Feeling, Understanding and Expressing, these tantalizing essays summarize Scott’s working methods, beginning with childhood years hunting and fishing, which established her lifelong profile as an avid outdoorswoman and lover of animals. Buy Now

Sandy Scott is widely recognized as one of the country’s premier animal sculptors and printmakers. Designed with highest possible standards, including a wealth of specially commissioned color plates and black-and-white photos, this book is meant to be savored and cherished. At its heart are Scott’s own thoughts and musings, compiled in her journals over the years. Organized into four chapters titled Seeing, Feeling, Understanding and Expressing, these tantalizing essays summarize Scott’s working methods, beginning with childhood years hunting and fishing, which established her lifelong profile as an avid outdoorswoman and lover of animals. Buy Now