Grandma’s farm consisted of five acres, mostly wooded except for a half-acre garden loaded with berries and vegetables. Out back stood a shed stuffed with old rakes and spades and other hand tools. Mason jars were scattered among bushel and berry baskets filled with tulip bulbs, all of it smelling like dirt and honest living. Behind the door hid two push mowers, the kind with reels and no motors. Grandma didn’t believe in Briggs and Stratton.

Trimmed in dark blue, the house proper had two bedrooms, one bathroom with an old fashioned, four-footed tub crouched against the back wall, a walk-through kitchen and a living/dining room.

Grandma believed in blue.

Faded blue curtains framed every window, and wallpaper decorated with tiny blue flowers covered the walls. We dried our hands on blue towels, put our dandelions in blue vases, and ate homegrown asparagus and corn, bacon-wrapped woodcock and grouse, and home-baked blueberry pie and biscuits off of blue plates.

“Why do you like blue so much. Grandma?” I asked her when it was my summer to visit.

Wiping flour on her blue apron, she reached for the rolling pin and worked the dough flat. “Well,” she paused, “have you ever seen anything bad that’s blue?”

I couldn’t think of anything except maybe the blue veins protruding on the backs of her hands when she pinched the dough around the pie plate.

“No,” I answered, unwilling to risk losing dessert. Grandma could paint the town blue for all I cared. I was just happy to be there, knowing what was to come.

“Now red, there’s a color full of the devil. Nothing but stop signs, cuts and bites and sailors taking warning. Yellow’s about as bad, all loaded down with caution and jaundice and ornery yellow jackets. And white and black are just opposites of the same. Ghosts and fog and other night things stuck inside nightmares. Green’s the color of envy and money, the root of all evil. Brown’s all mixed up with dead grass and leaves clogging the ditches.

“Blue, though, that’s God’s color,” she continued. “On Sundays when he’s resting, I picture him lying on the sky like it’s a blue carpet or maybe a blue bedspread to pull around himself until he’s ready to slip into some trunks for a dip in Lake Superior. Blue water surrounded by blue spruce the last time I saw it. Or maybe even the Atlantic. You know your grandfather came me from across the ocean.”

Sighing from the memory, she wiped flour from a small sapphire wedding ring and then laughed. “About the only bad blue I know is what those old ladies at church put in their hair!”

“Flaring Broadbills,” a gouache painting completed in the 1940s.

My grandparents met in New York at the turn of the previous century. Serving as a cook in a large upstate home frequented by the Roosevelts, Teddy himself, she claimed. Grandma fell in love with her British sailor and suitor who deserted the Royal Navy for her. I never knew the order or the truth of things, but I knew most of the stories. Grandpa was born to a bobby in London, lived in an orphanage, lied about his age and joined the navy at 16, served on the H.M.S. Blenheim, attended the opening of the Kiel Canal where he saw the Czar, met and married Grandma, joined vaudeville, settled in northern Michigan, opened a general store where my father and uncles worked, and died before I understood death.

“Why’s Grandpa lying down in church. Grandma?”

When she hugged me, she smelled like lilac and wore a blue dress.

“He’s just sleeping, child. Soon he’ll be hunting and fishing with God.” It was the only time I heard sadness in her voice.

Truth be told, from the picture albums stacked in the corner of the farm, I knew that both of them hunted and fished. There were stringers of trout or ducks pushing against the edges of every snapshot. My favorite showed them leaning against a Model A, legs crossed and arms akimbo, both wearing waders, shoulders touching, his to hers, Mona Lisa smiles curving their lips and straw hats tilted low over their eyes like a couple of cowboys. Even though the photograph was black and white, I just knew Grandma’s shirt was blue.

Tucked in one of the albums was an envelope stuffed with old duck stamps with their names scrawled across them.

Two of each, the oldest from 1937 depicted three geese descending, cost one dollar and was issued by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The last purchased were issued by the U.S. Department of Interior in 1960 and featured a Labrador with a mallard in its mouth. I know because I still have them.

“Which are your favorites. Grandma?”

She didn’t hesitate. “1938,1949,1953,1956 and 1960.”

“Why those?” I asked, thinking she would tell me stories of special hunts.

“They’re all blue.”

“1938 is green.”

“The ducks on it are bluebills, I believe.”

“Or redheads.”

“Close enough,” she observed.

Most of the summer I worked side by side with Grandma, planting crops and picking berries and learning the fine art of farming on a small scale. She taught me how to block lettuce and space corn kernels in a row so later the stalks wouldn’t crowd each other. Cucumbers we planted in mounds and, on those nights when frost was possible, we covered our tomato plants with bushel baskets. I learned to differentiate weeds from carrots and radishes, and how to lay out strings for the peas to climb. I hoed beans, shucked corn and dug potatoes. Some days she sent me over to the neighbors to pull mustard out of the potatoes and to turn over bales of hay lying in the field so they wouldn’t rot.

Illustration by Bob White.

“Dime a bale and penny a weed,” the neighbor man insisted, even when Grandma sent me back with the money. Between the neighbor’s pay and the 50 cents per quart of red and black raspberries we sold to the local grocery, I pocketed decent money for a boy in the 1960s. I knew I was going to need it.

Come a cool August morning. Grandma handed me a piece of toast covered with blueberry jam. Smiling, she said, “Well, young man, you’ve been working awfully hard for a good two months. I think it’s time for some hunting lessons.”

Grandma walked from her bedroom carrying an old 16- gauge Remington humpback that I had seen her pose with in the pictures. She had pulled on a pair of worn blue jeans under her blue-flowered dress. Ducking into the shed, she emerged dragging a flour sack full of empty soup cans.

“First things first,” she said, dropping the bag and cradling the gun in her arms like her firstborn. “You know how Grandma on hot mornings gets up like molasses, slow like she’s stuck to the sheets nearly, but on cool mornings she rolls out of that bed like mercury from a broken thermometer? Shooting’s like that, only in between. You can’t be molasses but you can’t be mercury either.

“Your Grandpa used to call it patient hurry,” she said. “And depending on the bird you’re hunting, you lean more towards one than the other. Woodcock, for instance, are closer to molasses. You know we got a farm full of them, but you won’t shoot many unless you let them stretch out like a yawn before you pull the trigger. Watch.”

She pulled two blue paper-cased Peters shells from her apron, loaded the gun and handed me a soup can.

“Now I want you to stand behind me and throw that can as high as you can.”

When I did, she lifted the gun to her shoulder without hurry and fired, crumpling the can at the peak of its flight.

“See? Molasses.”

She picked up the empty shell casing and handed it to me. “If you cherish the land you hunt, you’ll pick up your empties.”

I took it from her hand and smelled the sweet, smoky residue. It was like gasoline; you shouldn’t like the smell but you do.

“Now throw me another can hard and fast, only this time level it out like a partridge.”

She mounted the gun fast and fired almost before the can flew past the barrel’s end, knocking it sideways on the climb.

“Grouse don’t yawn. They’re quick, like mercury.”

Much of August was spent on lessons. Grandma and me rising early to practice molasses and mercury, and the safety required for hunting and shooting. She taught me how to carry the gun safely, barrel pointed high or low and left or right or middle, depending on where she stood. Later we marched mornings abreast in the cornrows, rain or shine. Grandma carrying a broom while I carried the 16-gauge, managing to keep in a line with her despite the eye-level cornstalks that obscured my vision.

She showed me how to cross fences correctly, handing her broom to me, crawling under the barbed wire in her dress and blue jeans, and taking broom and gun from me before I slid under. Again and again I practiced loading and unloading the gun, gaining confidence and skill.

Eventually, Grandma pitched soup cans from behind me—like a “New York Yankees pitcher,”—sometimes high like a woodcock, sometimes low like a rabbit, sometimes straightaway like a partridge. When I missed, she would invariably yell at me.

“More mercury!”

“Too much molasses!”

“Well, I sure struck you out on that

one, sonny!”

“Bean soup’s got your number, boy!”

By August’s end I had shot up all of my earnings but rarely missed, blasting the labels from nearly every can she tossed. The day I crumpled my first double, beef barley and tomato, Grandma shook her head in praise.

“You shoot better than your Daddy did at your age.”

At supper that evening she presented me with three new blue shotgun shells, much as she had to my father and my aunts and uncles and older cousins.

“These are for you,” she said. “Tomorrow you can start hunting the bird feeder.”

Hunting the bird feeder were magic words in my family. All of us, even the girls, worked Grandma’s farm for this last practice and prelude to field hunting. Whooping at dawn’s first light on the third weekend of September, I rushed to the shed, lugged out a bag of cracked corn and sunflower seeds and filled the feeder to the brim, spilling some on the ground.

Located at the far end of the strawberry patch because Grandma believed seed would distract more birds than any scarecrow, the faded blue feeder stooped with age, and the wooden post had begun to rot, despite a coating of creosote. The animals didn’t care though. Crows, grouse, turkey, pheasants, rabbits, ducks, squirrels, songbirds, deer, chipmunks . . . they all came.

My instructions were to wait for in-season game (squirrels, grouse, rabbits, woodcock, crows) and then fetch Grandma, who would bring the gun and oversee the hunt.

Cocky like most novices, I positioned a milk crate on the edge of the strawberries 10 yards from the feeder and hunted with the high expectations of youth. By noon barely a songbird had visited the seed and my confidence sagged.

“Well?” she hollered from the window.

“Nothing yet.”

Bringing me a sandwich, she noticed my slouch.

“You look like a fern in a fall frost,” she laughed. “Most days two of everything’s out here and I’ve had half a mind to give Noah a call. What do you think you’re doing wrong?”

When I shrugged, she laughed again.

“Did you think a partridge was just going to walk right up to you? You have to hide, boy.”

“How?”

“Well, that blue spruce could use some trimming.”

By mid-afternoon, I had built a branch blind with Grandma’s help and, by evening, rabbits and squirrels surrounded the feeder. Each time I stood to get her, though, they scattered wildly at full throttle. No matter the animal, I couldn’t get a jump on them and spooked them repeatedly. Vexed, I gave up at sundown.

Grandma sat in a rocking chair by the west window looking like Whistler’s Mother while knitting a blue scarf in the low light of the setting sun. Mischief tugged at the corners of her mouth.

“See much?” she asked cheerily.

“Couple of rabbits and squirrels, but I scared them off when I went to get you. It was pretty slow.”

“Well,” she paused, “that’s most of what hunting is. Looking around and enjoying and appreciating what God’s given us. It’s not so slow when you learn how to look and listen. Hey, did you see any woodcock picking at that seed?” A small smile dimpled her cheeks.

“No. I didn’t even see that doe and fawn we’ve been seeing most mornings and evenings.”

“Which way was the wind blowing.”

“I don’t know.”

“You have a lot to learn, kiddo.”

Learn I did. Although I never shot anything at the bird feeder—none of us did—I learned that woodcock eat worms, deer scent like bloodhounds and a turkey’s vision rivals the best binoculars. I learned about stealth and stalking, and how to pattern the arrival and departure of game. I understood how to use the wind to my advantage and how to ambush deer coming from a bedding area or leaving a food plot. I heard pheasants cackle for the first time in my life and laughed at myself for thinking partridge drumming was some farmer’s tractor starting in the distance. I listened to bright red cardinals whistle at their girlfriends and watched dandelion yellow finches hang like circles of sunshine from the feeder while black-capped chickadees cracked sunflower seeds with ease. I distinguished fox squirrels from grey and red squirrels, and recognized the difference between a button buck and a doe by their body shape. I knew a hen pheasant from a grouse in flight and the difference between a crow’s nest and a squirrel’s nest.

Most of all, I learned the patience required to look and listen. By the time Grandma took me on my first hunt, autumn already worried summer with early frosts, splashing pink, red and yellow across much of the landscape. Once green and lush, most of the ferns were browning and a cool afternoon breeze chilled our skin as we walked to the back woods where a small stream meandered through the property before spilling into a marshy bog.

Quivering with anticipation, I slipped one shell into the chamber, all that Grandma would allow, and breathed deeply. No sooner had my boot sunk into the muck when two woodcock launched like miniature helicopters, wings whistling and beating as fast as my heart and shot. Both birds spiraled toward the tree canopy unscathed before leveling off and disappearing.

Chagrinned, I looked at Grandma. “Too much mercury, I know.”

“Timberdoodles one, hunters zero,” she replied. “Just remember what I taught you and you’ll even the score.”

I remembered. Flushing a single into zigzagged flight, I paused my hurry as the bird yawned right.

“Can of soup,” I whispered, bringing the gun to my shoulder and firing. The bird fell in front of Grandma, who brought it to me and placed it in my hand.

“It’s the color of November,” I murmured, elation and sadness choking my voice.

“I know what you’re feeling.”

She paused, watching me struggle with grief and joy. “It makes you feel like you shot a poem. That’s part of it, too, knowing that you’re killing something beautiful. Understanding that makes you humble and teaches you reverence for everything God gives us.

Don’t ever lose that feeling. It makes you a better hunter and a better man, which is the purpose of hunting anyway.

Come on now, I think we’ve been invited to a dance.”

I followed her to the edge of the woods that opened onto a small field, once an orchard, with tall grass and a few apple trees scattered around it. At one end, the sun promised Indian summer, a fading red balloon floating over the horizon. At the other, a harvest moon rose big and bright, glowing golden orange in the evening sky.

Already the woodcock had gathered everywhere and nowhere, bowing and rising one second and gone the next, poetry dipped in twilight as they prepared for the journey south. Singles, tens, a hundred if there were 50, bird after bird darted past, evening acrobats twisting and spinning until more twittered above in helter-skelter, awkward grace.

We watched astounded until the dance subsided. When the sun eased below the treeline, we followed the moonlit path back to the house, our first and last hunt together.

The next morning my summer with Grandma ended and I returned home.

Grandma has been gone many years now. Once a year, I visit her grave where on her marker below her name is printed “Molasses and Mercury,” words my daughters now understand. At her funeral we all wore something blue in her honor and my father delivered the eulogy. Just before he spoke, he took three blue shotgun shells from his pocket and placed them on the lectern. We laughed and cried and cheered and some of us held up the three cartridges she had given us as kids. Dad reminisced about the farm and thanked Grandma for being a “rare and special mother and the best of hunters.”

Dad spoke about her love for blue and made us laugh when he reminded us of the soup cans and the old broom she carried in the field. Most of all, he talked about the gift Grandma had given to each one of us and asked that her great grandchildren receive the same one.

“Teach them to hunt,” he said. “You won’t go wrong.”

Then he walked to where she lay and placed his three shells in the pocket of her blue dress.

“Just in case the angels need some shooting lessons,” he whispered, and I remembered thinking that if anyone could teach angels to shoot, it would be Grandma.

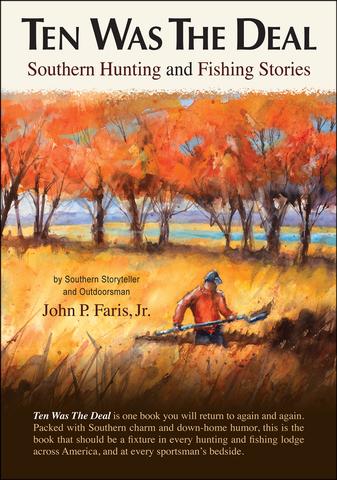

Ten Was The Deal is more than a book of stories about hunting and fishing, it offers all of the enchantment of yarns spun while sitting on the tailgate of a pickup truck; all of the lore of tales told around a campfire. Ten Was The Deal is definitely a keeper. John’s stories are set in pinewoods, along Piedmont streams, in Lowcountry fields, or along the coast of the Carolinas. This volume reveals a boy’s journey to manhood: turkey hunting with a grandfather, duck hunting with a dad, and sharing his first kiss with a fishing buddy. Buy Now

Ten Was The Deal is more than a book of stories about hunting and fishing, it offers all of the enchantment of yarns spun while sitting on the tailgate of a pickup truck; all of the lore of tales told around a campfire. Ten Was The Deal is definitely a keeper. John’s stories are set in pinewoods, along Piedmont streams, in Lowcountry fields, or along the coast of the Carolinas. This volume reveals a boy’s journey to manhood: turkey hunting with a grandfather, duck hunting with a dad, and sharing his first kiss with a fishing buddy. Buy Now