Sportsmen often quote Theodore Roosevelt’s comments on hunting and conservation, but his views on sporting life went far beyond his spoken words.

Through his writings and actions, Roosevelt laid down fundamental guidelines that every hunter can learn from, if not totally agree with. In The Wilderness Hunter and Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, Roosevelt expressed his opinions on hunting big game across North America. In African Game Trails, he visited the Dark Continent and blended local opinions with his views from the American West. Though some of his viewpoints were colored by his time period, many are timeless lessons that every hunter can draw wisdom from.

The Cardinal Sin

“On this day I got rather tired, and committed one of the blunders of which no hunter ought ever to be guilty; that is, I fired at small game while on ground where I might expect large.”

“On this day I got rather tired, and committed one of the blunders of which no hunter ought ever to be guilty; that is, I fired at small game while on ground where I might expect large.”

— T. Roosevelt, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

Roosevelt was after bighorn sheep when three jackrabbits crossed his path. He had previously written about the wariness a hunter needed to pursue sheep, but not seeing game for some time had left his trigger finger itching badly.

He wrote that one rabbit practically begged to be shot, being “perched on a bush, and with its neck stretched up.”

He knelt, fired, missed and instantly regretted his hasty decision—off in the distance an animal stirred and disappeared without Roosevelt or his companion ever learning if it was a sheep or not.

When you target a species to hunt, stick to that animal.

Never Give Up

“I fired into the bull’s shoulder, inflicting a mortal wound; but he went off, and I raced after him at top speed, firing twice into his flank; then he stopped, very sick, and I broke his neck with a fourth bullet.”

— T. Roosevelt, The Wilderness Hunter

Elk are infamous for absorbing lead like a sponge and offering no visible reaction in return. In this 21st century age of one-shot kills and long-range shooting, many hunting guides are frustrated by their clients’ refusal to anchor elk with follow-up shots. The first shot hits perfectly behind the shoulder and the shooter takes a victory lap, leaving the guide to watch as the bull races off to parts unknown.

Roosevelt had poor eyesight and sometimes reached beyond his effective shooting range, but if he had cartridges left and the animal was still in sight he never stopped firing until the animal was secured.

There’s always hope as long as there’s lead in the air.

Measure Distances Accurately

“Distances are deceptive on the bare plains under the African sunlight. I saw a fine Grant[‘s gazelle], and stalked him in a rain squall; but the bullets from the little Springfield fell short as he raced away to safety; I had underestimated the range.”

— T. Roosevelt, African Game Trails

Theodore Roosevelt didn’t have mil-dots, rangefinders or computerized scopes, but if he had he might have chosen to use them. Some hunters disdain technology and feel it has no place in the grand tradition of hunting, but within reason it can a blessing and not a curse. Make small changes to your equipment list, like a rangefinder, and see if the accuracy is worth the electronic convenience.

Hunting with or without modern devices is a personal choice. However, don’t let nostalgia rob you of the chance at more, and more ethical, shots.

Roosevelt in full hunting regalia. Photo courtesy Theodore Roosevelt Center.

Don’t Play The Numbers Game

“The mere size of the bag indicates little as to a man’s prowess as a hunter, and almost nothing as to the interest or value of his achievement.”

— T. Roosevelt, African Game Trails

Roosevelt and his son Kermit kept only a dozen or so of the 512 African animals they killed while on safari. The vast majority of the animals went to museums as exhibit specimens or were used for meat. He wrote that the two had not killed even a hundredth of the animals they could have if they had been willing.

As a foreign dignitary and arguably the most popular man in the world at the time, the only bag limit imposed on him in colonial Africa was the one within his own conscience. Roosevelt knew a full bag limit doesn’t necessarily mean a full day.

Judge your days afield on the memories made, not the shots fired.

Be Sure of Your Target

“The cowboy’s chapfallen face was a study; he had seen, in the dim light, the two ponies going down with their heads held near the ground, and had mistaken them for bears…He knew only too well the merciless chaff to which he would be henceforth exposed; and a foretaste of which he at once received from my companion.”

— T. Roosevelt, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

Being sure of your target not only entails the animal itself, but the space beyond and before it. Shooting an illegal animal can occur if the hunter doesn’t look for sex characteristics or minimum size requirements. Other hunters can also be injured or killed if a shooter blasts away into brush without identifying the target.

“Merciless chaff” is the minimal amount of punishment a hunter should receive if a shot isn’t taken safely and intelligently.

Recoil from Recoil

“When I first came to the plains I had a heavy Sharps rifle, 45-120, shooting an ounce and a quarter of lead, and a 50-calibre, double-barrelled English express. Both of these, especially the latter, had a vicious recoil…I threw them both aside.”

— T. Roosevelt, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

The quote reads a bit hypocritically coming from a man who “carried a big stick” and shot heavy-for-game calibers. For Roosevelt, the gun he settled on was the .405 Winchester. The gun’s dimensions and buttstock gave it a reputation for self-inflicted punishment, but to TR it was a fun rifle that did what he wanted.

For him, the .405 was adequate for every species he wanted to hunt. He felt happy with it’s performance, and with more and more trigger time, Roosevelt gained the experience needed to shoot the rifle well.

The point is not to shoot a .243 Winchester for moose, but to shoot something you—not your friends—can shoot well. If you flinch you fail, and failure in the woods could lead to an animal being maimed or dying a painful death.

Shoot a gun that you look forward to shooting again.

Theodore Roosevelt and his son Kermit sit atop a Cape buffalo taken during their famed African safari. Photo courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Respect Your Elders

“As I ate, he gradually unbent and talked quite freely, and before I left he told me exactly where to find the band, which he assured me was located for the winter, and would not leave unless much harried.”

— T. Roosevelt, The Wilderness Hunter

Not everyone is blessed with a hunting mentor in their family. Roosevelt was born in New York City to social elites, and while his family encouraged young Theodore in his pursuits of taxidermy and the outdoors, there was no one in the home who could teach him firsthand.

Whether it was a guiding outfitter in Maine or an old trapper in the Bad Lands, Roosevelt sought out experienced hunters in whatever area he was in and drank in the advice they offered. Many opened doors to incredible hunting grounds, while others shared harrowing tales of bear attacks and more.

Thankfully, there are programs under various stage agencies that partner hunters with experienced sportsmen and women to teach them the way of the woods. No matter your background or level of expertise with rifle or shotgun, everyone can benefit from a tutor.

Never be afraid to ask for help.

Be Humble

“Then they dashed off, and I missed one shot, but with my next, to my utter astonishment, killed the last of the band, a big buck, just as he topped a rise four hundred yards away.”

— T. Roosevelt, The Wilderness Hunter

Roosevelt believed pronghorn were the hardest targets for the American rifleman. The orb-like eyes sitting on top of their goat-like heads help antelope search the prairie for danger. A hunter can be miles away and still illicit fear in a herd. Roosevelt estimated every buck killed would cost the hunter twice as much ammunition as a white-tailed or black-tailed deer.

To combat this, a hunter had to be willing and able to stretch their shots over hundreds of yards. Roosevelt—whose shooting has become the stuff of legend, if not ridicule—was under no illusions that he was the Annie Oakley of hunting. He took long shots, but he was honest enough to acknowledge his many misses and not brag when he shot well.

Be man or woman enough to admit when a shot hits home in spite of, not because of, your best efforts.

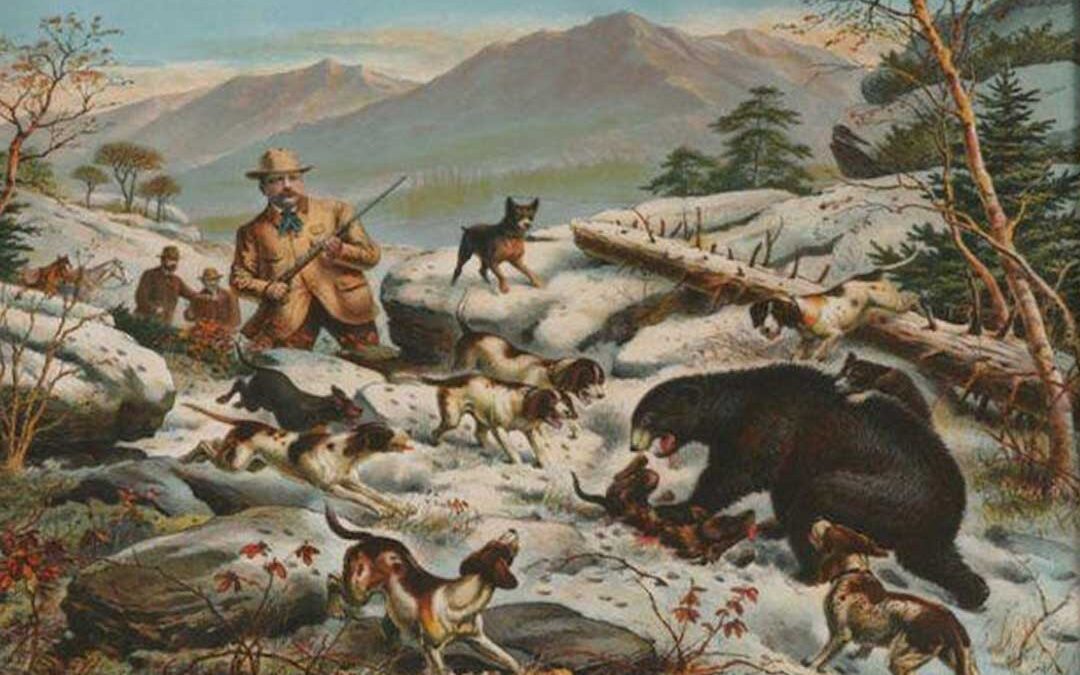

Over The Limit by John Seerey-Lester

Be Honest

“One of my men walked up to the fallen beast, bent over it, and then asked, ‘Where did you aim?’ Not reassured by the question, I answered doubtfully, ‘Behind the shoulder;’ whereat he remarked dryly, ‘Well, you hit him in the eye!'”

— T. Roosevelt, The Wilderness Hunter

In the same vein as good shooting, be willing to own up to your mistakes when you take shots you shouldn’t have. The hunting adage of, “If you’ve never missed, you haven’t been hunting long enough,” is true.

Roosevelt followed this story by saying he and his companions were in need of meat, and therefore had purposefully stretched their shooting abilities. Starvation is one of the few excuses for attempting risky shooting, but its still nothing to be proud of.

Sometimes bad shots end happily like this one, but other times they lead to maimed and suffering animals dying out of reach. Take ethical shots or no shots at all.

Stop and Smell the Roses

“From morning till night I was on foot, in cool, bracing air, now moving silently through the vast, melancholy pine forests, now treading the brink of high, rocky precipices, always amid the most grand and beautiful scenery; and always after as noble and lordly game as is to be found in the Western world.”

— T. Roosevelt, The Wilderness Hunter

Hunting, especially hunting done in the wilderness, is about more than the animals pursued. Roosevelt only spent a few years in the Badlands, but he relished every occasion to camp or chase game. Many of his accounts feature descriptions of the camps he pitched or the sights seen from horseback.

Though he shot a lot of trophy-caliber animals, the rack or skin was always a piece of the prize and not the only reward. Enjoy holding the antlers, but look outside the scope from time to time.

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s “Legends Series” relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation.

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s “Legends Series” relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation.

The large-format, 200-page book covers Roosevelt’s most active years as an outdoorsman from the 1870s until his death in 1919. It also relives the hunting and exploratory expeditions of his two sons in the Far East. It opens with Roosevelt’s first deer hunt as a teenager, then continues chronologically as he pursues such dangerous game as grizzlies, lions and elephants in Africa and North America.

Acclaimed wildlife artist and the preeminent painter of Theodore Roosevelt, John Seerey-Lester takes you on a historic journey to some of the most interesting places on earth. John’s paintings and writings will make you feel as though you are there, sharing the exciting adventures of the former president. Buy Now