For weeks on end, deadly man-eaters would plague Arthur Neumann’s safari.

The English hunter, Arthur Neumann, was still recovering from a terrible mauling by an angry cow elephant in the Lake Rudolph area of British East Africa (now Lake Turkana, Kenya). The year was 1896 and Neumann was already recognized as one of the greatest elephant hunters of his era, though the stomping and goring by the elephant had left him temporarily crippled.

He had been laid up at his camp in Kere for several months and now, at age 46, it was beginning to look like his elephant hunting days might be over. His native help had taken him on a crudely constructed stretcher made from two tent poles and a sheet to his camp several miles away.

It was intended that he would convalesce more comfortably at his own camp, which was close to the kraal of a local tribal leader and all his resources. But after being there for so long without medical aid, Neumann’s condition was not improving.

The nights were long and uncomfortable; he was forced to sleep while propped up or sitting in a camp chair. Neumann felt as though he was suffocating from being cooped up in the tented camp in the sweltering heat. Making his situation even more unbearable were the incessant mosquitoes and tsetse flies.

Night after night he would lay propped-up, unable to sleep as he stared at the roof of the tent and listened to natives singing in the distance. He longed to hear the crowing cock in the nearby kraal, heralding the morning and some relief to his nighttime misery.

During these long nights, he had plenty of time to think about all the bad luck that had befallen him since the beginning of the year. It all began in late afternoon on January 1st, 1896, after arriving at Lake Rudolph from South Africa. Neumann had been sitting in his chair by the river near his camp when he heard an unearthly scream. Raising his head, he saw a ghastly sight.

His manservant, Shebane, was in the mouth of a huge crocodile that was swinging round and heading back into deep water with the young man in his jaws. Shabane had been screaming and flaying his arms and legs, but now he was silent. Then, while gripping the boy by the waist—like a fish in the bill of a heron—the croc swirled around and disappeared with its prey.

Nothing could be done for the poor lad, even though some members of the party wanted to follow the beast with guns and a boat. That idea was soon put to rest and the grieving and mourning began. The young servant had worked for Neumann for two years and had been a valued member of his caravan. He would be greatly missed.

Considering his own run-in with the elephant, things had not gone as planned that year. The rains had come and turned the dry savannah green. The rivers were bulging, the waterholes were full and the game was plentiful, but Neumann was still not in any condition to hunt; in fact, he was unable to walk.

Eventually, Neumann moved his camp back to El Bogoi in the Samburu region of the Great Rift Valley. Still unable to walk, he had to be carried most of the way by his native helpers. But Neumann was unaware that the move would not bring an end to his troubles.

It was June by the time they arrived at their camp and Neumann’s injured right hand had become swollen and was extremely painful after being pricked by a thorn when attempting to put some wood on the fire. It turned out that the hunter was suffering from blood poisoning, which had swelled his hand to an enormous size and caused excruciating pain.

While Neumann was laid up with his injured hand, the camp was struck by an even more tragic incident. One of the natives was digging out a beehive when he was attacked by a lion and carried off —in broad daylight. This was followed by another native who was snatched by a man-eating lion while warming himself by the fire.

Neumann had experienced several encounters with man-eating lions soon after he arrived in British East Africa in 1890. He had hooked up with an expedition organized by Sir William Mackinnon who was to reconnoiter a proposed railway route to Lake Victoria from Mombasa.

It was during this expedition that Neumann and some other members of the foraging party took time to do some hunting. Neumann managed to kill five elephants and five hippos on the trip, which he found most exhilarating.

It may well have been that experience that resulted in Neumann’s decision to become a professional elephant hunter, even though some 38 members of his party were killed by Maasai warriors during their return journey. Apparently it was in retaliation for the confiscation of Maasai cattle by a previous expedition.

The route eventually selected by Neumann’s expedition was also used by the infamous Uganda Railway. Nicknamed the “Lunatic Express,” the railroad line suffered a series of deadly attacks by marauding maneaters that would ultimately kill hundreds of railway workers.

Now, some six years later, Neumann’s safari caravan was facing a similar pattern of attacks by lions that seemed particularly daring and dangerous. He had to take steps to protect his men as well as the donkeys and cattle. Neumann began by setting-up baited gun-traps, similar to ones he’d used in the past. The traps seemed to be the best solution, for two reasons: There was a shortage of marksmen in his caravan, and Neumann was unable to hold and shoot a gun with his right hand.

The men set a gun-trap at the head of a ravine the lions had been using. A thick piece of meat was tied tightly to the muzzle of a snider carbine resting in the fork of a tree branch. The butt of the gun sat in the fork of another branch; a string was looped round the trigger, then tied to the tree branch holding the stock. The rifle sat loosely in the contraption, so when a lion took the bait into its mouth, it would shoot itself.

From sunset until 3 a.m., the camp remained quiet until the silence was shattered by a loud bang, followed by a savage roar and a series of growls that quickly faded away. There was no doubt that a lion had shot itself.

At daybreak, Neumann was helped into the ravine to see what had happened. Two men with guns assisted him as he glassed the opposite side of the valley for any sign of the lion. He could see a lion’s ear sticking up in the grass, but it was not moving. As he and the men approached cautiously, they could hear something moving beyond the dead lion.

Suddenly, another lion broke cover and ran up the opposite hillside. The natives took some snapshots, but none hit home. When the lion reached the top of the hill, it was in clear view as it ambled broadside to Neumann, who attempted a shot that missed the fleeing cat.

Although Neumann was pleased with the trap-killed lion, he realized there was still at least one more man-eater out there somewhere. This made him very uneasy yet determined to bag the other culprit. It wasn’t long before his worst fears materialized in the form of another death; but this time, it affected him badly.

Neumann had improved sufficiently to collect more specimens for the museum, but he was still unable to withstand the rigors of elephant hunting.

And so, he decided to lead a few of his men on a forage to the coast. Accompanying Neumann was a Ndorobo tribal leader, who accidentally took them the wrong way. Because of the delay, Neumann was unable to reach his planned campsite by a stream and was forced to stay overnight in an exposed area of the mountains.

He was very uneasy about camping in the area as there was very little material to make a strong boma for protection from the lions. He considered setting up a baited gun-trap in the hopes of bagging the escaped man-eater. Unfortunately, a heavy downpour brought a halt to construction of both the boma and the trap.

The boma was only half built when the men bedded down for the night beneath a single tree on a small knoll, with Neumann’s tent a few yards away. When the rain stopped, a fire was lit and a store of wood was collected for the night.

Neumann hardly slept as he kept thinking about the possible presence of the man-eaters. He sat staring through the open tent flap, watching the dying embers. Unbeknownst to Neumann, all the natives had gone to sleep and no one was keeping guard.

He had just drifted off into a light sleep when he was suddenly aroused by a loud commotion, which he immediately realized was a lion attack. Among the vicious growls, he could hear screams and shouts amidst a tremendous scuffling noise very close to camp.

Neumann grabbed his rifle and raced out into the dark, but by the time he got to where the commotion had taken place, the lion had already taken off and two natives were shooting into the dark. The unseen lion responded with growls that gradually faded away into the night.

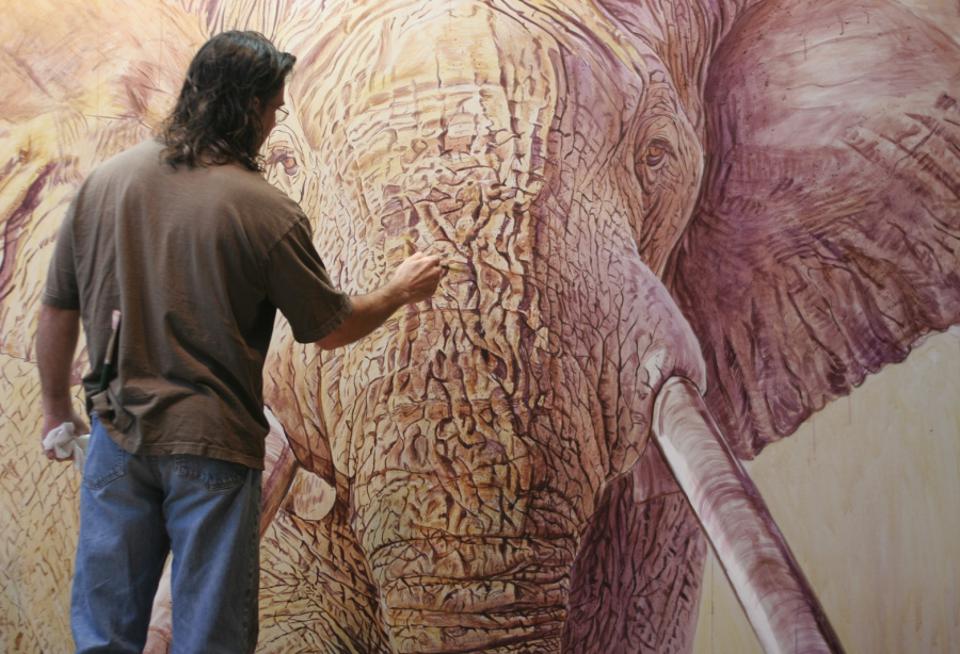

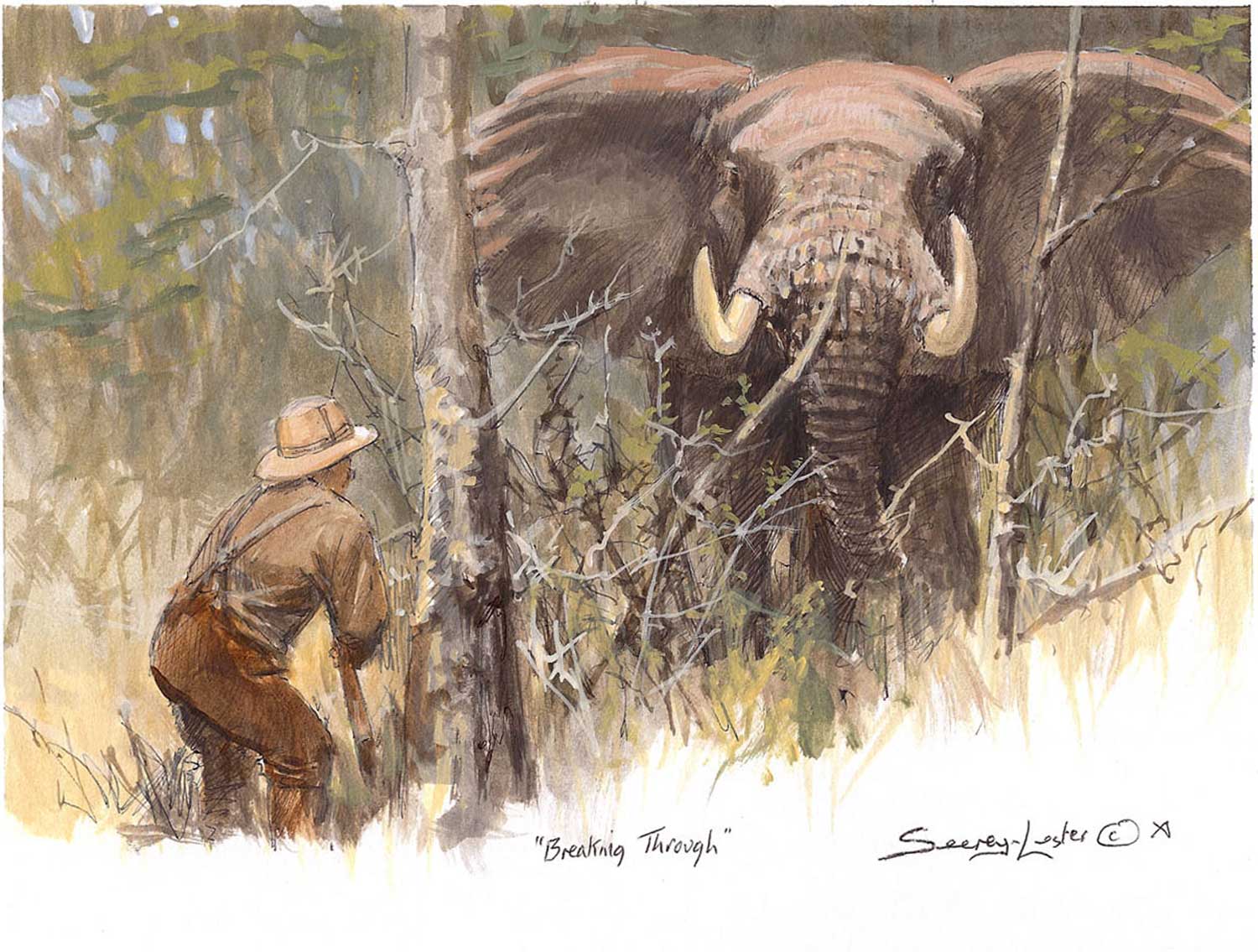

Distant Camp Lights by John Seerey-Lester.

The agitated natives were shouting and pointing at the blood-stained grass at the site of the attack. It soon became obvious that the lion had taken one of his men.

“Who was it?” he asked, as he looked around at all the shocked faces.

The men just stared in silence at Neumann who suddenly realized that the lion had taken Squareface, his long-time gun bearer and valued companion.

There was nothing to be done in the dark; they would have to wait for first light to investigate further. The native helpers were anxious to move on and Neumann knew if he didn’t take charge immediately, he would have a mutiny on his hands. He felt guilty about exposing his men to such danger, but he wanted to avenge Squareface’s death.

All the men gathered round Neumann’s fire and were instructed to keep it lit all night. The conversation around the fire was at first agitated, but soon simmered down to an eerie silence as one by one the men fell asleep.

At first light, Neumann woke Juna, his remaining gun-bearer, and the two men set out to follow the cat’s trail. The lion’s tracks were easy to follow in the damp grass, and it wasn’t long before they came across vultures feeding on the remains of poor Squareface. It was a horrific sight.

Having eaten his fill, the lion had gone back into the forest, but unfortunately, its tracks were no longer visible. The two men returned to camp where they found the dejected natives already packed and ready to move on.

Neumann still wanted to avenge his man’s death, but none of the natives were willing to stay behind with him. So, they soon returned to El Bogoi where the story of the lion’s attack continued to be the topic of conversation among the natives. Neumann, incidentally, never got over his own mauling and the loss of Squareface. The following year, Neumann returned to England to recuperate and set to work writing his autobiography.

Besides a rumored brief visit to Africa in 1901, Neumann never recaptured the elephant hunting success of his youth. He attempted to acquire a parcel of land and sought a government post in the Guasso Nyiro River area of the British Protectorate. Sadly, he was granted neither, and after writing a short note, he committed suicide at his home in central London on May 29, 1907.

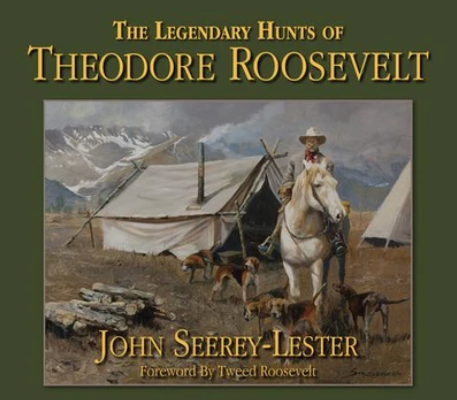

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now