The relevant and meaningful question isn’t “Which breed is best for pheasants?” It’s “Which breed is right for me?”

No upland gamebird engenders so much disagreement, disputation and plain, unvarnished discord as the ring-necked pheasant. Other gamebirds are rarely the targets of invective— Has an ill word ever been uttered against the bobwhite quail? Has anyone dared profane the character of the ruffed grouse?—but the pheasant’s critics are legion. And vocal. “Ditch parrots” is the preferred term of derision, although a grouse hunter of my acquaintance, a man who was about as politically incorrect as they come, leaned toward “heathen Chinee.” He was enthusiastic about killing them; he just wasn’t all that keen on hunting them.

The most memorable line I’ve heard in this vein was authored by a dead-serious quail hunter, a guy who ran champion pointers and German shorthairs. I’d innocently invited him to join me on a pheasant hunt in Iowa.

“I’m not about to waste my dogs’ talents on those goddamn ditch parrots,” he snorted. “It’d be like hitching a Ferrari to a honey wagon.”

Even the legendary Ben O. Williams, who makes this sport look so effortless that he’s been called “the Zen master of upland bird hunting,” admits that he’s no great fan of the ring-neck. Indeed, he once wrote a piece for Pointing Dog Journal, “Why America’s Favorite Gamebird Isn’t Mine.” The root of Ben’s antipathy, which underpins much of the sentiment in the anti-pheasant camp, is the way those sneaky, snaky roosters tend to mess with a dog’s head, making him overly cautious, if not downright tentative, and generally turning him inside out.

Of course, this applies mostly to pointing dogs, although the one time I hunted pheasants with Ben (in South Dakota, just FYI) my recollection is that his Brittanys and pointers performed to their usual high standard. He pulled in his horns and only ran two at a time, however, not the four he typically turns loose when he’s chasing Huns and sharptails back home on the high plains of Montana. Hell, in that big country he frequently runs five or six, sometimes as many as eight. It’s a sight to behold.

Still, when someone voices his dislike for pheasants and/or pheasant hunting, those who take the opposing view don’t make a federal case out of it. They engage in some good-natured banter, toss in a barb or two and “agree to disagree,” as they say.

Express an unpopular or even mildly controversial opinion about pheasant dogs, on the other hand, and you’d better be prepared to put up your dukes. Out of the universe of gundog owners, pheasant hunters are by far the touchiest, testiest and thinnest-skinned. They’re invariably spoiling for a fight, their antennae up 24/7 for some slight, real or imagined, that’ll give them a reason to become righteously pissed off.

As a person who’s often asked to write about pheasant dogs and the qualities they ought to possess, I’ve learned the hard way that you can’t win for losing. Speak in glowing terms about a specific breed and you get hanged in effigy by guys who insist it’s the Edsel of hunting dogs. Hint that another breed might not be the most appropriate choice for ringnecks and its supporters will rip you up one side, down another and then lap up the blood. Suggest that certain kinds of dogs should perform in certain kinds of ways and an angry mob who believes just the opposite will queue up to pelt you with rotten fruit.

It’s not pretty, and I bear the psychic scars to prove it.

I’m at a bit of a loss to explain all this barely suppressed hostility, but while I have a couple theories, I’m keeping them under wraps in the interest of self-preservation. A “contributing factor,” though—and I’m willing to state this for the record—is that there’s simply less consensus, and therefore more disagreement and room for partisanship, regarding dogs for pheasant hunting than there is for any other form of the sport. There’s the whole flusher vs. pointer thing, for starters, a non-issue (or at best a minor one) with respect to most other gamebirds but a huge one—and an endless source of contention—when it comes to the ringneck.

The bottom line, though, is that you can successfully hunt pheasants with any properly trained flushing or pointing dog. The relevant and meaningful question, then, isn’t “Which breed is best for pheasants?” It’s “Which breed is right for me?”

In order to answer this question, of course, you need to ask yourself several others. For example, is your priority not so much finding birds as it is optimizing the opportunities you know you’re going to have and maximizing the “recovery rate” of the birds you shoot? If so, your best bet is a flushing breed (springer, cocker, Lab, golden) or one of the closer-working pointing breeds, such as the German shorthair, German wirehair, Deutsch drahthaar, or wirehaired pointing griffon. I’ve heard (i.e., been forcefully reminded) that the Italian spinone can do a creditable job on pheasants as well.

In this same vein, if the thought of a dog bumping birds out of range makes you want to put your fist through something, you definitely want a flushing dog or, again, a very close-working pointing dog. My personal opinion is that pointing dogs shouldn’t be required to stay within gun range (and aren’t intended to), but I’m not the last word on the subject. I don’t think ketchup belongs on hot dogs, either, and apparently most of the world disagrees with me about that.

The thing about wider-ranging pointing dogs—pointers, setters, certain strains of Brittanys and German shorthairs—is that you must be willing to accept the risk inherent in their hunting style. Even the very best of them will, from time to time, accidentally bump a bird, and every so often a bumped or wild-flushing bird will trigger that most dreaded of pheasant hunting scenarios—the cover-emptying “cluster flush.”

The reward for running a dog that hunts beyond gun range is the possibility of finding birds that you’d otherwise never see, much less enjoy throwing a shotstring at. The rooster I killed to finish my limit on a hunt in North Dakota a couple of seasons ago offers a perfect case in point. My English setter, Tina, had made a cast to my left to check out a clump of snowberries along a fenceline. It was a logical place to look, and when the Garmin Alpha signaled Point!, the readout told me she was 85 yards away—not far in the grand scheme of things, but plenty far enough to have saved that rooster’s hide were it not for Tina’s initiative and my willingness to let her take it.

Generally speaking, the bigger the country, the lighter the cover, and the more thinly the birds are distributed, the greater the advantage of having a wider-ranging dog. It’s the mathematics of ground coverage, pure and simple. When the cover’s tight and the birds are more concentrated, conversely, the advantage shifts to a dog that works close. I’d even take this a step further and argue that in extremely heavy cover—cattails, brushy shelterbelts, anything that’s a real struggle for a person to walk through—a flushing dog’s the only way to go. If you’ve ever tried to flush a rooster in front of a point while breaking through skim ice and choking on cattail fluff, I needn’t say more.

Whether a dog points or flushes, stays close or ranges wide, if it doesn’t make an honest, tenacious effort to hunt dead and retrieve, it’s not a pheasant dog. Period. Obviously this is where Labs and goldens really shine, and as a broad rule of thumb the continental/versatile pointing breeds (GSPs, drahthaars, wirehaired pointing griffons, etc.) are stronger in this respect than pointers and setters are. It’s just not weighted as heavily in the pointer-setter blueprint, although given the proper training and encouragement most of them can become competent retrievers— and occasionally spectacular ones.

Of course, this is all to sidestep the inconvenient truth that as long as you’re able to walk, shoot and identify birdy cover, you can kill pheasants. I know a guy who hunts in South Dakota every November. He stays at the KOA campground in Presho, walks road ditches and says he gets his limit every day. He doesn’t own a dog.

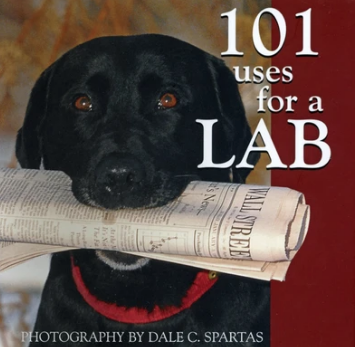

A whimsical look at the many roles your beloved Labrador Retriever plays in your life. Just a sample of his many hidden talents include canine garbage disposal, security alarm, world-class athlete, border patrol agent, devoted fishing buddy and low-cost dishwasher.

A whimsical look at the many roles your beloved Labrador Retriever plays in your life. Just a sample of his many hidden talents include canine garbage disposal, security alarm, world-class athlete, border patrol agent, devoted fishing buddy and low-cost dishwasher.

This picture book consists of photos and short captions describing some of the myriad ways in which Labrador Retrievers and their humans interact. The adorable and hilarious photography in this book perfectly captures all the heartwarming, endearing characteristics that make him your best friend. Buy Now