A dog needs to be in training for no less than three months. If a trainer indicates they can get the appropriate training done faster, good luck!

Tell me what you think about the following statements:

“Hello, Ms. Jordan. This is Johnny’s first day of kindergarten and he is very excited. However, you can only teach him for one month to be sure he is ready for college.”

“Johnny, say hi to Coach Ron. We are very excited about Johnny deciding to play football, Coach. Please teach him how to play and we will pick him up before the NFL draft next month.”

“Hello, Mr. Kaplan. Johnny is taking the SATs in four weeks. Please teach him the 2,500 or so vocabulary words he may see on the test.”

These requests are, of course, ridiculous. Now ask yourself, why is it any different with your dog? I cannot believe the number of telephone calls that I receive in which the owner wants the dog trained in two weeks or a month.

Trained to do what? The dog often has not had many birds, has never had an e-collar, and, although the owner denies it, its retrieve is terrible. Except for very specific training on single issues, a dog needs to be in training for no less than three months. If a trainer indicates they can get the appropriate training done faster, good luck.

The reason for the three-month minimum is pretty simple: It is about the longest that many owners will send their dog away for training. It is also about the minimum time it takes to get the dog performing regularly for the owner when they take the dog home.

Let me give you two extremes in client dogs that came to me for training. The first is a very talented English springer spaniel that is both well-bred and young (7-8 months when it came in for training). The first month, we introduced the dog to quail and pigeons so it would get out into different cover and hunt for birds. We also began the foundation work for obedience. The second month, we introduced the dog to gunfire and completed e-collar conditioning and obedience in the yard. The third month, we transferred compliance to the field and started the dog on its proper ground coverage (proper use of the wind).

At the end of three months the owner came and got his dog. He now can take the dog out and hunt, and has already gone to the hunt club with his friends and shot birds over the dog. His dog complies with both verbal and whistle commands, hunts within gun range, and retrieves.

Most importantly, when the dog needs to be corrected the foundation is in place; the owner can make a mild correction with his voice, whistle or e-collar and the dog does not shut down.

We were able to move the dog along quickly because a) it was a genetically talented dog, b) it came to us at a young age with limited issues, and c) the dog would already retrieve consistently.

Training requires commitment, both on the trainer’s and the owner’s part. (Photo by Christina Power Photography)

At the other end of the spectrum is the dog that comes in for training and either will not retrieve or “kills” birds, meaning the bird is not fit for the dinner table. And we’re not talking about the dog that will not bring the bird back, either. We’re talking about the dog that will not pick the bird up at all.

We cannot do anything with a dog until it will retrieve or stop killing birds. That means we need to complete the “forced retrieve,” which takes one to two months to complete.

Our standard on the retrieve is very high. We’ve had many dogs in for training that have been through the forced retrieve and still only retrieve some of the time. In our program that is unacceptable, as are dogs that destroy birds worse than a shotgun blast. Train them right the first time and it saves you money and aggravation later. If it is going to take one or two months to get the retrieving fixed, it will obviously take longer to train your dog to an acceptable level.

If it just will not work for you to send your dog out for training, consider joining a training group. Try to find one that allows you to work under the guidance of a quality professional trainer.

About the Author

Todd Agnew is a Eukanuba Pro Trainer and has been training field bred spaniels since 1997. He participates in spaniel field trials and hunt tests in both the United States and Canada, guides hunters for wild gamebirds, and is a professional dog trainer that firmly believes in the value of exposing hunting dogs to wild gamebirds. “If a dog can produce the wild bird that the fox, coyote, weasel, and hawk missed, then they would be of a caliber that any hunter would be proud to own.”

Todd has won and placed in numerous spaniel field trials and has developed numerous dogs that have won and placed in spaniel field trials and passed spaniel hunt tests. More importantly, he has produced and help train numerous shooting dogs that please their owners.

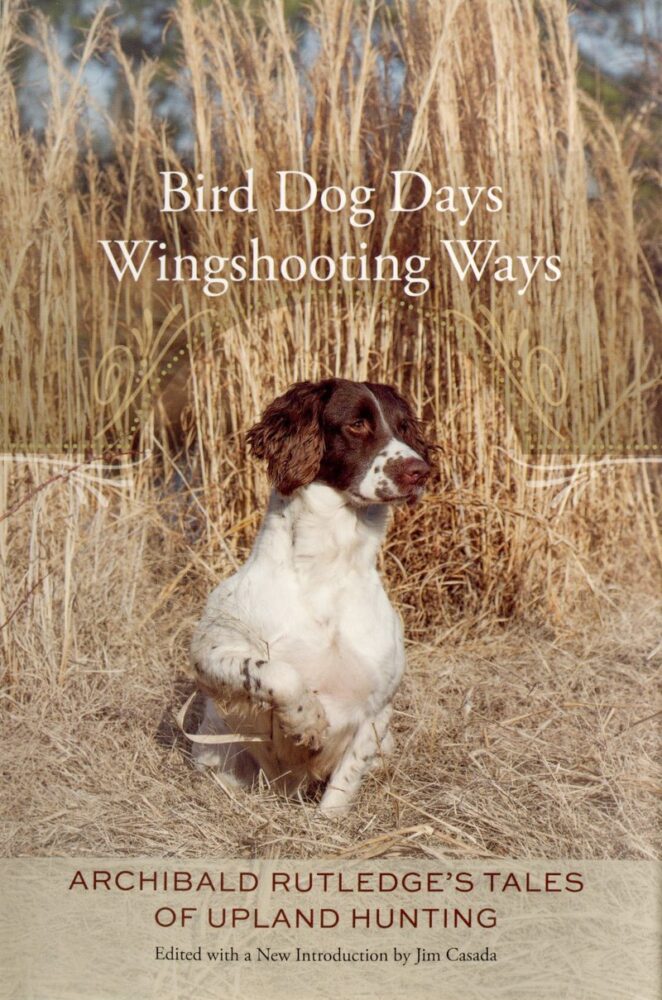

This collecti on, first published in 1998, turns to Archibald Rutledge’s writings on two subjects near and dear to his heart that he understood with an intimacy growing out of a lifetime of experience—upland bird hunting and hunting dogs. Its contents range from delightful tales of quail and grouse hunts to pieces on special dogs and some of their traits. Bird Dog Days, Wingshooting Ways also includes a long fictional piece, “The Odyssey of Bolio,” which shows that Rutledge’s literary mastery extended beyond simple tales for outdoorsmen. Shop Now

on, first published in 1998, turns to Archibald Rutledge’s writings on two subjects near and dear to his heart that he understood with an intimacy growing out of a lifetime of experience—upland bird hunting and hunting dogs. Its contents range from delightful tales of quail and grouse hunts to pieces on special dogs and some of their traits. Bird Dog Days, Wingshooting Ways also includes a long fictional piece, “The Odyssey of Bolio,” which shows that Rutledge’s literary mastery extended beyond simple tales for outdoorsmen. Shop Now