Once the explosions stopped, the men rose gingerly to assess their predicament.

The three hunters lay sprawled in the dry grass. One was on his back, groaning and rubbing his arm, while the other two were slowly recovering and checking themselves for injuries. Their overturned jeep, from which they had been unceremoniously ejected, lay a few feet away on the rocks at the foot of a steep slope.

The men were assessing the damage to their vehicle and themselves when there was a sudden loud whoosh as the jeep burst into flames.

Thankfully, they had been thrown clear, but as the men scrambled to recover what they could from their scattered belongings, there came the first in a series of explosions as the ammo in the glove compartment began to cook. The men threw themselves on the ground as their stock of 500-grain .458 Magnums, .270s and shotgun shells fired off, sending bullets whizzing over their heads.

Once the explosions stopped, the men rose gingerly to assess their predicament.

The year was 1979, and the hunters were outdoor writer Peter Capstick and his friends Karl Luthy and Christian Pollet. The three men were hunting in the Sidamo Province along the southern Ethiopia border.

At that time the region was a dangerous place to hunt because of the shifta (bandits) who were robbing and even killing villagers and tourists. But it would prove that on this safari the three men would have more to fear than the shifta.

Luthy lived in Africa, so he knew, perhaps more than his companions, what a difficult situation they were facing. They had no vehicle, and to reach camp they would have to hike some 60 miles. Very little had survived the crash when their jeep rolled down a steep slope and flipped over onto its roof. The ensuing fire burned up most of their essentials.

They began to gather things together for the forced march ahead. They had a hatchet, a couple of quart-size water bags, Luthy’s large folding skinner, Capstick’s Swiss Army knife, two rolls of film, a .270 rifle, a 12-gauge shotgun, a handful of .270 cartridges and shotgun shells. They also had five .458 rounds, which were useless, as they had lost both rifles of that caliber.

They decided to sleep on-site the first night rather than try to navigate the terrain in the dark. They would head out in the morning. Luthy lit a fire while Pollet did another search near the burned-out vehicle for anything they might have missed.

Luthy doubted they would find water between their location and camp. In the 110 degree heat of the day, the men would soon run out of water. They could probably survive on no food for the duration of their journey, but not without water.

The Dawa River was just north of their camp, so the men decided not to waste time searching for waterholes en route, but head straight cross-country for the river.

Their first night was thankfully uneventful despite the area being known for man-eating lions. They divided the night into three watches, but those who were not on watch slept fitfully. At first light all three woke to aches and pains from their ordeal of the previous night and their tumble to safety from the vehicle.

The men trekked through the thornbrush and searing heat, hindered by their injuries and the hidden rocks in the short dry grass. The going got harder and harder as they struggled up and down the gullies; there seemed to be no end to their arduous journey.

As the sun began to disappear, the three men collapsed and reveled in the thought of resting for the night. They realized that their precious water would soon run out, as would their energy. Their bodies were torn and tortured by the thorns, and it wouldn’t be long before they were too weak to go on. They all had the same thought—that the hyenas would probably take them as they slept.

For two more pain-filled days the men marched on through the cruel, sun-parched terrain. There had been an obvious shortage of game on their journey, with not even guineafowl for the shotgun. So it was a pleasant surprise when they came across a warthog, which Pollet bagged for supper with the .270.

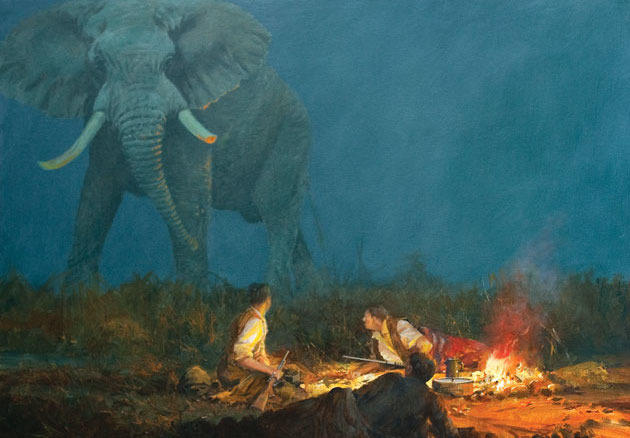

It was another chilly night as the men rested their weary bones around the fire. Their stomachs filled after gorging on the hog, they sparingly sipped the last of the water before settling down for the night.

Suddenly, the peace was shattered when a bull elephant came crashing out of the darkness. For a moment it stood some distance away, then in a threatening manner it charged into the circle and glow of the fire.

Capstick knew it was useless to try and kill an elephant with a shotgun, but struck with the fear of someone who is about to die, he stood and fired at the eye of the bull. The shot had little effect except to anger the beast even more. The elephant rolled its trunk, tilted its head back, and let out a deafening scream.

Desperately, Capstick worked the pump as the elephant kept coming. He raised the gun for another shot, when to his surprise he heard a bang and caught sight of a gun-flash out of the corner of his eye.

He looked back at the elephant as it fell to the ground. Capstick quickly spun around and saw Pollet eject a spent cartridge from the .270 and carefully hand-feed another into the chamber.

Pollet slowly walked up to the fallen beast and put two more shots in its heart. Capstick and Luthy couldn’t believe it. How had he done that?

When the two men examined the spent cartridge, they found that Pollet had somehow, under pressure, taken the 150-grain soft-point bullet apart with his teeth and reversed the point so it fired base-first. In this configuration it had penetrated the elephant’s brain and killed it instantly.

On examining the elephant, Luthy found a musket ball lodged at the base of his tusk that had caused the big bull to suffer great pain, which seemed to explain his aggressive behavior.

Using Luthy’s skinning knife, the men removed the front part of the elephant’s stomach, which contained a large amount of water. The men carefully transferred the precious liquid into their bottles, which lasted them for the remaining 20 miles of their journey. All three got back to their camp safely.