Elsewhere, man-eaters were quickly shot. In Corbett’s India, they kept killing.

Deeply rutted pads and a cleft across the right forefoot distinguished the prints of the eldest cat. The toes were also exceptionally long. By February 1929, the tigers – by their sign an old female and her grown cub – had killed at least four dozen people over three years. Women cutting wheat in the field were saved only when one of the beasts was spotted and the alarm raised. The tigers retreated into the jungle.

A couple of days later, hunter Jim Corbett was shown to a ravine where a cow had been killed the previous night. The spoor led into thick cover, where he spied the protruding leg of the luckless cow short yards ahead. Suddenly it jerked. The big cats were there, feeding!

“On hands and knees, and pushing the rifle before me, I crawled through the bracken….” He paused in the shelter of a big rock, then climbed it. The animals were 20 steps away. “Both tigers appeared to be about the same size, but the one was several shades lighter than the other; and concluding that her light coloring was due to age…I aligned the sights very carefully on her, and fired. At my shot she reared up and fell backwards.” The other cat disappeared “before I could press the second trigger.” Corbett’s elation was short-lived, “for I had made a mistake and shot the cub – a mistake that during the ensuing 12 months cost the district l5 lives….”

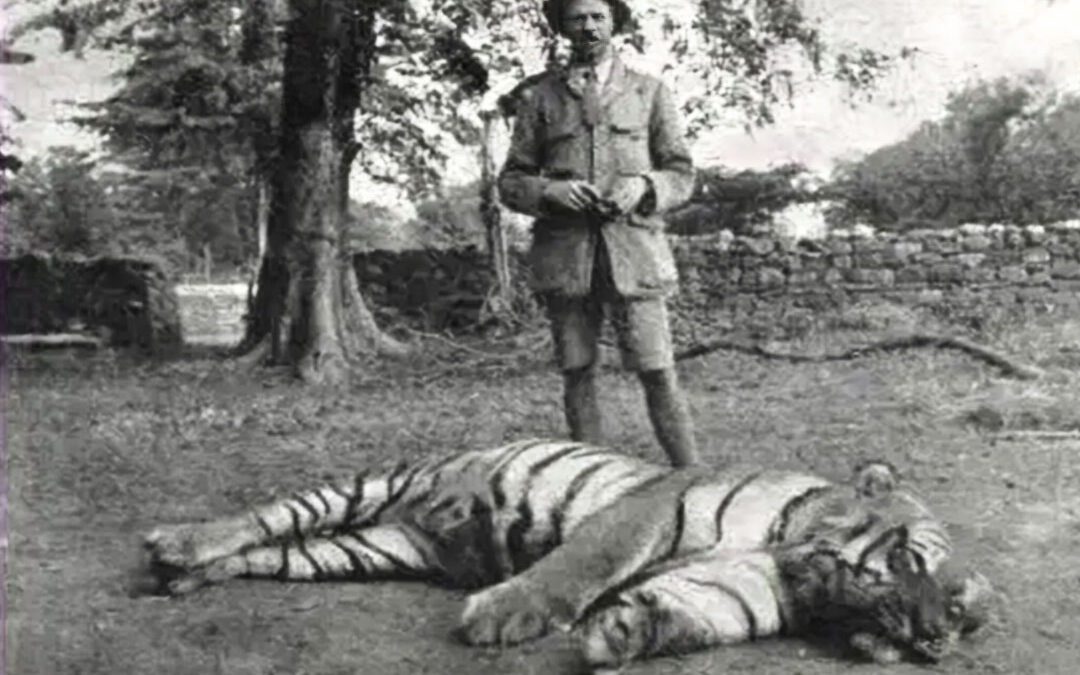

Jim Corbett

The Kumaon hills lie hard against the Himalayas in the far northern United Provinces of India. It was into this country that Edward James Corbett was born July 25, 1875, youngest of 13 children. He was four years old when his father died. His mother raised the family on their Naini Tal estate, and at a cottage 15 miles away. Fascinated early on by nature and keen to explore surrounding forest, young Jim tracked animals, collected birds’ eggs and learned to hunt. He had great affection for wildlife. Even tigers.

“When I see the expression … ‘blood-thirsty as a tiger’ in print, I think of a small boy armed with an old muzzle-loading gun – the right barrel of which was split for six inches of its length, and the stock and barrels [lashed by] brass wire – wandering through the jungles…when there were ten tigers to every one that now survives; sleeping anywhere he happened to be when night came on, with a small fire to give him company and warmth, wakened at intervals by the callings of tigers [but knowing] a tiger, unless molested, would do him no harm…. I think of him on one occasion stalking [guinea fowl and] creeping up to a plum bush and standing up to peer over, the bush heaving and a tiger walking out on the far side and, on clearing the bush, turning round and looking at the boy with an expression on its face that said as clearly as any words, ‘Hello, kid, what the hell are you doing here?’… And then again I think of the tens of thousands of men, women and children who, while working in the forests … pass day after day close to where tigers are lying up and who, when they return safely to their home do not even know….”

When he wrote that, 50 years after he’d met the tiger in the plum bush, Corbett had spent 32 years “in the more or less regular pursuit of man-eaters.” But first he worked to support his family, starting at age 18 for a railroad company. During the Great War he served as captain of the 500-man 70th Kumaon Labor Corps to France. Promoted to Major after armistice, he traveled to India’s Northwest frontier to command the 114th Labor Battalion in the Third Afghan War. From 1920 to ’36, after his 20-year railroad career, he spent months each year in East Africa, supervising coffee and maize production in the shadow of Kilimanjaro. He hunted there too, but by 1930 he’d largely turned from killing game to filming it. He did, however, continue hunting man-eating cats. All told, he dispatched 19 tigers and 14 leopards, his last in 1938. Corbett was a life-long bachelor. He died in Kenya, April 19, 1955.

Corbett’s best-known of five books detailed his hunts for man-eaters. It appeared shortly after WW II.

Jim Corbett’s government service, wilderness skills and quiet intelligence impressed authorities desperate to rid precincts of man-eaters. His courage, physical stamina and determination brought results denied lesser men. Three of his five books, beginning with Man-eaters of Kumaon at the close of WW II, describe in detail his perilous hunts for India’s most notorious tigers and leopards.

There’s no evidence Corbett sought fame. Of an early assignment, he wrote, “I heard of the tigress shortly after she started killing human beings [but] did not consider it would be sporting of an outsider to meddle in the matter,” When he agreed to hunt her, after “the toll of [victims] had risen to twenty-four,” he admitted he had little experience with man-eaters “and had no idea where to look for her.”

A second Corbett book on man-eating cats appeared a decade after his first. It’s equally compelling!

The Muktesar tigress, as would become evident, had earlier lost an eye to a porcupine, which also imbedded some 50 quills up to 9 inches long in her right foreleg. Suppurating sores ensued. Hungry and hurting, she bedded. A woman cutting grass for her cattle came too close and was killed. Short days later, a man happened by the animal’s next bed. He died quickly too; but the tigress tasted his blood, and for the first time ate human flesh. A day later she killed again, to eat. By the time Corbett began his two-day walk to Muktesar, she was a practiced killer.

Villagers welcomed him, pointing out a small orchard two miles off, in a valley 1,000 feet below. He started for it early, and soon met a small girl leading an ox. The beast was stubborn; Corbett walked with her to help. She learned he’d come to kill the tiger. He learned it had just taken her uncle’s bullock.

“Do you know it is a man-eater?” he asked.

“Oh, yes,” said the eight-year-old. “It ate Kunthi’s father and Bishon Singh’s mother, and lots of other people.”

“Then why did your father send you with his ox to your uncle’s plowing? Why didn’t he come?”

“Because he has malaria.”

“Have you no brothers?”

“I had a brother, but he died long ago.”

They delivered the ox to her uncle, and Corbett insisted on walking her back home, on the road that had yielded several kills to the tiger.

Corbett spent uncomfortable (and terrifying) nights waiting over bait, but also used beats to get a shot.

The girl’s parting directions to the dead bullock led Corbett to the drag mark, then to the carcass, partly eaten. Only a rose-smothered tree was close enough for a shot after dark; however, loath to miss any chance, Corbett braved the thorns to reach a make-shift perch. The white bullock lay 15 feet from the muzzle of his .500 double. Night fell, clouds veiling the stars. A stick snapped. Then soft steps stopped at his tree. The tiger bedded, invisible. Corbett stayed very still. Presently he heard the cat rise and approach the kill. But the blackness was so complete, even the carcass had melted into the night. The tiger blew before feeding, to dislodge hornets drawn to the meat in the heat of the day. In vain Corbett strained to see. He decided to aim by ear. Turning his head slowly back and forth, adjusting the rifle’s position to suit, he was at last satisfied the barrels were aligned with the man-eater.

When he fired, the tigress bounded off. The growl that followed suggested a miss. Corbett’s perch had sagged over the hours. Once 10 feet up, it was now eight, and “my dangling feet considerably lower.” Three cigarettes later, he heard another growl. There was no reason for the animal to stay, but it had. Then the rain started – “a heavy downpour.” Corbett had dressed lightly. There was no canopy to his tree. After five hours, just before daylight, the rain stopped, replaced by an icy wind.

When daylight brought his village hosts, Corbett found his bullet had struck the carcass a hand’s breadth from where the tiger’s head had been.

Shortly he organized a beat with 30 men in the steep, rocky, brushy canyon to which the tiger had retreated. It proved too big and too thick a place. But en route to his post, Corbett had come upon a cow killed by a tiger a week earlier. Good fortune put him back on the ridge above that carcass after the failed beat. Approaching, he heard a bone crunch. She was feeding, in daylight, just yards away!

Suppressing the urge to look, lest the movement alert her, he waited. Presently she stopped, but instead of emerging on his slope, crossed the drainage. He could see her form winking between saplings as she climbed. “With the forlorn hope that my bullet would miss the saplings and find the tigress,” he aimed quickly and fired. Instantly the cat “whipped around, came down the bank, across the hollow, and up the path on my side.” The bullet had splintered a sapling near her head; she couldn’t place the shot.

Unwittingly Corbett had pulled the one card he wanted. “Waiting until she was two yards away, I leant forward and with great good luck managed to put the remaining bullet … where her neck joined her shoulder.” She narrowly missed him as momentum carried her over the precipice into the stream below.

Corbett’s 450/400 killed the Chuka man-eater mere feet away. Right: the brother of her last victim.

It seems strange now, when the killing of a human by an animal brings quick official response, that an agency would let dozens die before hunting the beast down. But early in the 20th century, natural hazards in wild places were better accepted. Native peoples suffered more than did European colonists, in Africa as well as India. The infamous man-eating lions of Tsavo claimed 28 rail workers before both cats were killed. But this appalling figure had less effect on official response than did resulting work stoppage on the railroad. And it doesn’t count the toll in nearby native villages.

Corbett was unable to find government records of man-eaters pre-dating 1905 in his part of India. Presumably this lack of data reflected the effort spent dispatching them. In 1907, when he was hunting the Champawat man-eating tiger, he was urged by villagers in the adjacent Amora District to rescue them from the Panar man-eater, a leopard of uncommon efficiency. Between them, wrote Corbett, these two cats killed 836 humans! Aware of the depredations, the government “had no machinery to put in action against them.”

There were sound reasons for delayed action: distance, transport and manpower. The Chowgarh tigers, for instance, roamed “an area of 1,500 square miles of mountain and vale, where the snow lies deep in winter and the valleys are scorching in summer…. Foot-paths, beaten hard by bare feet, connect the villages.” Reaching the site of a kill could take a day, even days of walking, by which time the beast would be gone. Few government agents had the skills to bag a man-killer. Priority lists resulted. Corbett noted this one at a District conference: “Three man-eating tigers operating at that time in the Kumaon District were classed as follows in their order of importance:

1st – Chowgarh, Naini Tal District

2nd – Mohan, Almora District

3rd – Kana, Garhwal District”

Corbett moved as quickly as he could to cross cats off that list. He pushed himself physically and took considerable risk to ensure he missed not a chance. When a man-eater was close at hand, he had the nerve to stay stone-still – or to sprint after it lest it escape. On a beat for the Champawat tigress, he loaded two of his three cartridges into his .500. Soon after he posted near an opening, the cat dashed through it. Corbett’s bullet missed. She broke cover again at 30 steps. Firing both barrels, he managed a less-than-perfect hit. The animal sped without visible distress into thick forest. Immediately, Corbett ran toward the beaters, grabbed from one a derelict shotgun and followed the tigress. Coming upon her, he raised the gun – then saw to his dismay a gap between barrels and breech! He fired. The gun held. So did Corbett’s luck. At that instant the beast died. He found later the ball from the borrowed smoothbore had missed.

At 436, the Champawat man-eater’s human tally distinguished her. For killing the tigress, Corbett was given a rifle by the London gunmaker, John Rigby & Co. Trim and lightweight, with a Mauser 1898 action barreled to 275 Rigby (7×57), it became his favorite arm. He would use it on man-eaters at ranges from 10 feet to 400 yards.

By April 1930, the Chowgarh tigress had killed at least 64 people. It had been more than a year since, from his rock perch, Corbett had mistaken the young animal for its mother. A year of frustration. But now he was again on her trail. In jungle that held vision to mere feet, a pair of rare bird’s eggs caught his eye. He picked them up. A few steps farther on, easing around a bend, he suddenly looked “straight into the tigress’s face.” She was 10 feet away. The eggs in his left palm, he wrote later, checked his reflexive urge to cheek the rifle – action that would have triggered the cat’s spring. Instead, with one hand Corbett eased the .275 across his chest. He felt “the swing would never be completed….” His arm was aching, his grip weakening when at last the rifle came to bear. His bullet smashed the man-eater’s spine and rent her heart.

Was the earlier killing of this man-eater’s offspring in vain? Surely it was learning its mother’s habits. But Corbett wrote that while cubs mimic the mother, eating what she eats and assisting with kills, he knew of no young tiger that upon leaving the care of a man-eating tigress became a man-eater.

Both tigers and leopards may take to human flesh when age or injury renders them unable to take wild prey, or when by twist of fate they’re incidentally exposed to fresh human remains. Corbett pointed out that unlike tigers, leopards also scavenge. Some have become man-eaters after finding human remains not yet given funeral rites. Hindus in the hills of Corbett’s homeland were often days bringing their dead to riverside for ritual cremation, exposing corpses to scavengers. Outbreaks of disease, and the occasional blooms of war dead, also drew leopards.

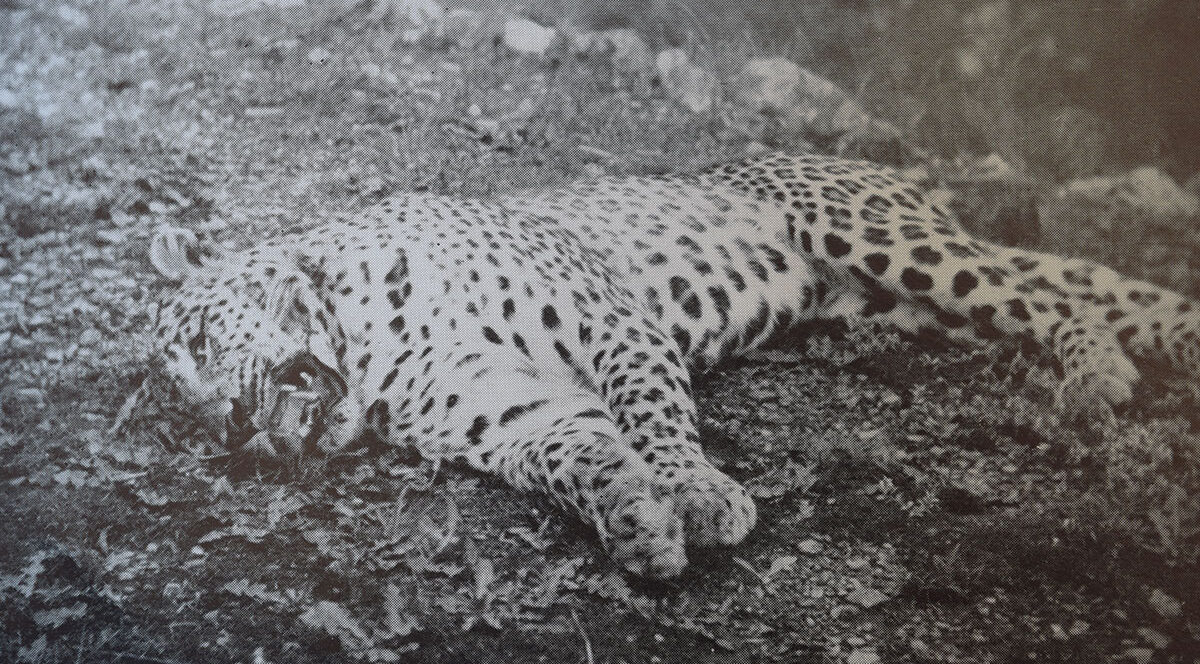

The Panar leopard was credited with 400 human kills. She almost got Corbett during his night vigil.

The Panar man-eater was one of two Kumaon leopards that became accustomed to human flesh in the wake of cholera and wartime casualties. Between them, wrote Corbett, these two cats killed 525 people. Like tigers, leopards “are semi-nocturnal forest dwellers.” They have much the same habits and kill in much the same way. But when a tiger becomes a man-eater, he observed, it loses its fear of humans and moves about boldly during the day. A leopard remains fearful of people, killing only when it has the sure edge, after dark. For these reasons, “man-eating tigers are easier to shoot than man-eating leopards.”

One night in April 1910, at a remote forest homestead near Lamgar, an 18-year-old girl sleeping in a bungalow was attacked by a leopard. The cat sank its fangs in her throat and would have made off with her but for the frantic response of her husband, who yanked her free and shut a door on the animal. That night and the next day the man dared not move from the room. His wife was in great pain as wounds on her throat and clawed breast turned septic.

Probing villages for information on the Panar man-eater, Corbett came upon the bungalow. Alas, the nearest medical aid was a day’s march behind him. After lying in wait for the leopard that night, he left to summon help. It would arrive too late.

In September, with five of his men, he started out again. The group arrived at Almora after a 28-mile walk, most of it in the rain. The fourth day of hiking, he entered a village, Sanouli, where the man-eater had taken a victim six days earlier. The cat lived in “a patch of brushwood” into which it carried its prey. As the villagers had no firearms, they endured the terrible night-time raids, up to four in one month.

Corbett bought two goats, tethering one near the brushwood. That night, the leopard killed and ate it.

When an acute malaria attack put Corbett down, his men tied the second goat where the first had been taken. Two days later the goat was still alive, and Corbett was recovering. Certain the leopard would now be hungry, he prepared to sit for it in an old oak. The only practical seat was a rotten branch 15 feet off the ground. He arranged for long blackthorn shoots to be lashed around the oak’s trunk. To maintain his balance, he “gathered the shoots on either side … between my arms and my body.” The goat was tied 30 yards away as he settled in. A strip of white cloth on the muzzles of his shotgun would help him aim during the dark of the moon, when the cat was most likely to come.

Night fell.

“I felt a gentle pull on the blackthorn shoots …. No question now that I was dealing with a man-eater, [a] determined man-eater at that. Finding that he could not climb over the thorns, the leopard [had] got the butt ends [in] his teeth and was jerking them violently, pulling me hard against the trunk….” The beast’s growls didn’t unnerve Corbett; they told him where it was and what it was doing. “It was when he was silent that I was most terrified …. Several times he had nearly unseated me….”

During one of those heart-stopping pauses, the cat leaped from the tree toward the goat, now no more than a pale blur in the dark. Corbett heard it struggle. When suddenly it went quiet, he pointed the shotgun in that direction and fired. “I saw a white flash as the leopard went over backwards.”

Exultant villagers were quick to the scene with pine torches. Corbett tried to dissuade them from looking for the leopard at night, but they insisted with characteristic faith and fatalism that the beast was dead. He convinced them, then, to follow single file behind him.

Fifty yards beyond the goat, the man-eater sprang from the darkness. The villagers “turned as one man and bolted.” Luckily for Corbett, they collided with each other in their haste, dropping their torches. The brief, flickering glow gave him enough light “to put a charge of slugs into the leopard’s chest.”

Corbett killed the clever Talla Des tiger after it had killed 150 people, including this lad’s grandfather.

Jim Corbett’s frequent bouts with malaria interrupted but didn’t scuttle his hunts. On the trail of the Talla Des man-eater, a tigress that had killed 150 people, he had muffed an early chance. Thereafter he felt a burden of responsibility for wounding an already lethal cat. He lamented: “I had come to Talla Des to try to rid the hill people of the terror that menaced them … and all that I had accomplished so far was to make their condition worse.”

The tigress proved devilishly elusive, partly because Corbett’s health during much of the chase was “far from normal.” Late in that hunt, “the swelling on my head, face and neck had now increased to such proportions that I was no longer able to move my head … and my left eye was closed ….” As that evening’s “shocks were stabbing through the enormous abscess, and the hammer blows were increasing …” he gathered his men and told them that if he didn’t return by the following evening to pack up his things “and start early the next morning for Naini Tal.”

That night the tiger’s spoor kept to established paths, enabling him to follow. Fatigue and malaria caught up, however, just as the animal came clear, a shadow in the darkness. Rather than take a risky shot, he climbed a tree with a lattice of branches and secured himself there, relying on resident langurs to warn him if the man-eater approached. At midnight his abscess broke.

Corbett slept. He would meet the Talla Des tigress the next day, at three steps, in thick bracken….

Content goes hereIn 1898 John H. Patterson arrived in East Africa with a mission to build a railway bridge over the Tsavo River. Over the course of several weeks Patterson and his mostly Indian workforce were systematically hunted by two man-eating lions. In all, 100 workers were killed, and the entire bridge-building project was delayed. Buy Now