In the dark night, the men sat listening. Originally no more than five feet from the last team member, Sgt. Phleger had disappeared.

As a Marine deployed to Southeast Asia 25 years ago, I had heard of tiger sightings in the bush and an incident where a Marine had been killed by one. I never ran across anyone, including intelligence people, who could verify this, as most unit reports were classified at that time as were maps. One day, however, I found the incident in Bruce Norton’s account of his time with 1st Force Recon. It is the only documented case of that attack I have seen.

By 1970 U.S. operations in South Vietnam had become so effective that continuous reinforcement of combat troops was required by the North Vietnamese enemy. Since the narrow northern border, the DMZ, was demarcated by the Ben Hai River and rolling, open country, it would have been impossible for the NVA to access large units undetected. Their preferred travel corridor was the trail complex running south through Laos and Cambodia known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Along the Trail, the NVA could move in; relative safety before entering South Vietnam through many remote access points along her western border. One in particular was an enormous, tree-covered basin called the A Shau Valley.

Because of its size and cover, the A Shau Valley became a staging and logistics area for thousands of NVA troops. To counter them, U.S. Marines inserted (by helicopter) small, usually six-man reconnaissance teams to report enemy activity and call in air strikes. Thirty miles from the nearest friendly units, these recon teams normally spent five to seven days observing and patrolling before being extracted.

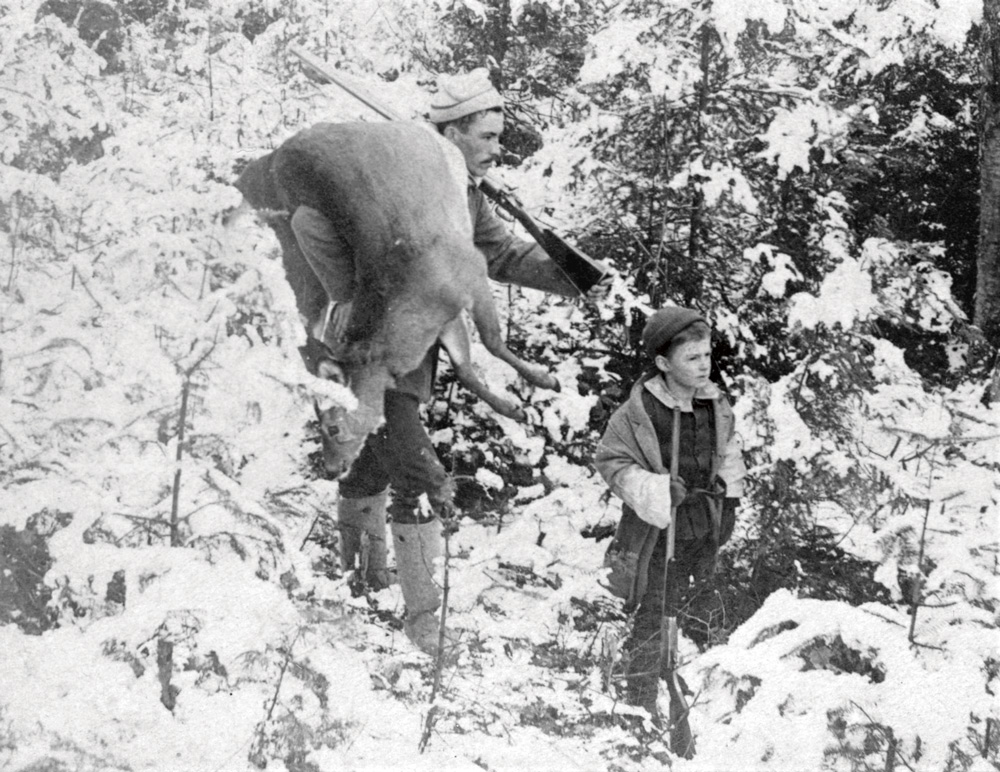

Sergeant Robert Cain Phleger, two days before he was slain and eaten by a Bengal tiger in the A Shau Valley of Viet Nam.

Referred to as Eden-like, the A Shau Valley was a wilderness of rugged mountains, dense jungle canopy and crystal streams and waterfalls. Unlike the cultivated, piedmont areas to the east, inhabitants were few. Animal life, however, was abundant. Deer, wild pigs and small apes lived in the A Shau and, since imperial times, the valley had served as a principal hunting area for Bengal tigers.

Sergeant Robert C. Phleger had joined 1st Force Recon initially as a radio specialist and later as an assistant team leader. With his considerable leadership ability and bush skill, Phleger was soon made leader of his own recon team. Cheerful, possessed of a dry sense of humor, Sgt. Phleger earned an outstanding reputation for developing the expertise of his men.

In April of 1970 Phleger flew to Hawaii for a hard-earned R&R and married his high school sweetheart. Shortly after his return to Force Recon, his team was slated for a five-day mission of reconnaissance patrols in the A Shau Valley. Having just returned from his R&R, and with not much time left in the country, Sgt. Phleger was told he was not to go out with his team.

Since the mission was relatively easy, Cpl. Jerry Smith could take over as the new team leader. Ever the professional, Sgt. Phleger refused, insisting to his lieutenant that he needed to accompany his men in the leader transition (this type of devotion to unit was common to Marines of that era). The lieutenant finally agreed, with the understanding that this was definitely Sgt. Phleger’s last trip to the bush and a safer job in the rear would be waiting on his return. Hence, Sgt. Phleger took charge of his seven-man team.

On the afternoon of May 5, 1970, the team was inserted near Razorback Ridge, so named for its height and 65 degree slopes on both sides. The team spent the rest of the day climbing the ridge. Once atop, the men set in for the night. Since the ridgeline was extremely narrow, there was no room to place the men in their usual 360-degree defensive position, so Phleger stretched them along the ridge with himself farthest out.

Sometime after dark, those team members on watch heard a sudden rushing movement in the dense brush, accompanied by several short muffled screams from Sgt. Phleger. The men radioed their lieutenant who told them to stay alert, that it was possible Sgt. Phleger had only experienced a nightmare and, awakening disoriented, wandered off into the brush.

In the dark night, the men sat listening. Originally no more than five feet from the last team member, Sgt. Phleger had disappeared. Had he been discovered and killed, or captured by some silent, stalking NVA soldier? Deep in enemy territory, the men could not call out his name, or give away their position with a flashlight. Eventually, several team members crawled to Phleger’s last position and felt for him in the darkness. Finding nothing, they crawled back in place and remained on 100 percent alert, weapons ready.

Daylight revealed Phleger’s rifle and other gear as he had placed them. Slightly farther out, the men found his hat and poncho liner — soaked in blood — with drag marks leading down the ridge to heavier brush. Suspecting they were being drawn into an ambush, Cpl. Smith radioed in and was told to follow the drag marks.

They did so and though all had seen Casualties before, none were prepared for their macabre discovery. Sgt. Phleger’s body had been completely devoured from the waist up. The team was attempting to radio when they were startled by the earth-shattering roar of a tiger less than 15 feet away. Several Marines fixed their weapons, but the tiger, which had obviously been lying there and had stood up to defend his kill, fled the scene unhit. Cpl. Smith then radioed the situation in and was told to prepare for immediate extraction.

As they gathered their gear, the tiger returned, this time positioning itself between the men and Phleger’s remains. Again, the men fixed at the cat which ran away. One team member hurled a fragmentation grenade at the tiger’s departing route, but it was never determined whether or not the animal was hit.

Once in the rear, an autopsy determined that the tiger had seized Sgt. Phleger in his sleep and broken his neck. Mercifully, he was dead before the tiger had begun eating him.

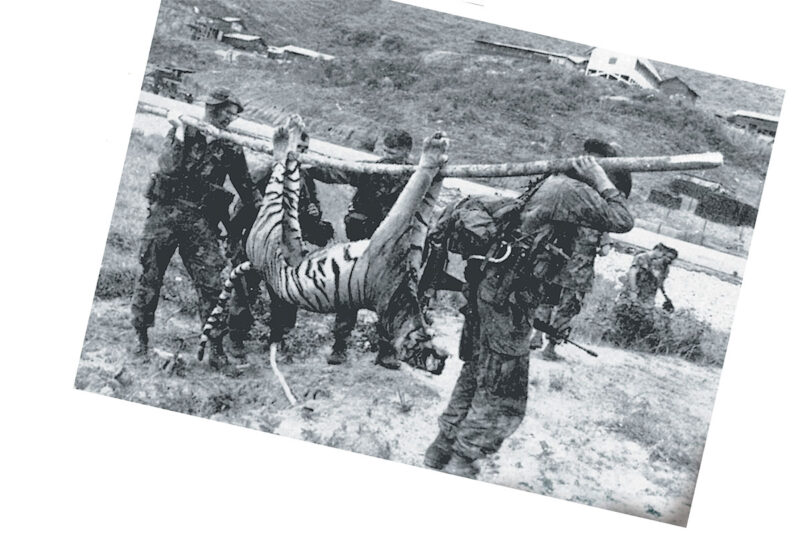

Sgt. Michael Larkins (in lead) helps to carry the 300 pound Bengal tiger that he killed several days after Sgt. Phleger’s tragic death.

Several days later, a recon team from a different unit awaited extraction from another area in the A Shau Valley. The big CH-46 helicopter landed, dropped its ramp, and the team rushed aboard. Their assistant team leader, Sgt. Michael Larkins, hung back on one knee in the prop blast, making sure all men were on board. From inside the aircraft, several team members suddenly noticed movement behind the sergeant. Since verbal communication was impossible over the screaming turbines, the men signaled to Larkins to turn around. He did so, raising his weapon and saw a tiger charging him! Sgt. Larkins fired a round toward the cat’s head. The shot turned the animal broadside and Larkins quickly emptied his magazine. The tiger fell dead less than 15 feet from Larkin’s position by the ramp of the aircraft.

Anyone familiar with helicopters and the deafening noise and virtual windstorm they create when landing has to be amazed at the audacity of this tiger. A CH-46 is a large transport helicopter with a span of over 90 feet needed to clear its front and aft blades which, in Larkins’ case, were turning with enough power to flatten the Surrounding grass. If a tiger wouldn’t be afraid to charge that, just what would it be afraid of?

The men retrieved the tiger and flew it back to the rear. Later, it was determined that the 300-pound specimen was not the same one that killed Sgt. Phleger. No wounds or marks were found on its body, and Phleger’s maneater was described as having been larger in size. The two teams had been operating some miles from each other, but I do not believe that to be a major factor as North American cougars, for instance, have been known to travel hundreds of miles in a short time. It seems likely that it was the same cat, possibly a wounded animal or one that associated men with food. Perhaps the medical examiners had failed to notice shrapnel embedded in the tiger from the grenade and that Phleger’s men never got a good enough look at the tiger to judge its size accurately? Most dangerous animals appear very large when seen for tile first time. It remains a mystery, yet there were no more reports of tiger attacks after the incident involving Sgt. Larkins.

This story, among many others, is featured in the latest anthology, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles available in the Sporting Classics Store.

This was a man who caught a world record Nile perch and ate it . . . a man whose prodigious snoring made him a pariah in any camp (and once nearly got him killed) . . . a man who was crazily and unashamedly in love with his dogs . . . a man who was as happy stalking tiny, jewel-like brook trout in the tumbling creeks near his Vermont home as he was stalking glowering Cape buffalo in the thorny heat of the African bush. His knowledge was encyclopedic, his imagination infinite, his sense of humor boundless. Bob Jones, you learn, was a writer’s writer, a man’s man and a fiercely loyal friend – if not someone whose friendship was always easy. In Jones’ company, you were never far from harm’s way.

This was a man who caught a world record Nile perch and ate it . . . a man whose prodigious snoring made him a pariah in any camp (and once nearly got him killed) . . . a man who was crazily and unashamedly in love with his dogs . . . a man who was as happy stalking tiny, jewel-like brook trout in the tumbling creeks near his Vermont home as he was stalking glowering Cape buffalo in the thorny heat of the African bush. His knowledge was encyclopedic, his imagination infinite, his sense of humor boundless. Bob Jones, you learn, was a writer’s writer, a man’s man and a fiercely loyal friend – if not someone whose friendship was always easy. In Jones’ company, you were never far from harm’s way.

And whether you’re among his legions of fans or someone coming to his work for the first time, A Roaring in the Blood, like running the rapids of a brawling North Country river, is a wild – but deeply rewarding – ride. It confirms Jones’ stature as a writer not only of uncommon gifts, but of enduring ones. Buy Now