The bear launched and hit the ground, eyes locked on me. Then, I heard my friend yell, “There’s two!” — A second later, “There’s three bears!”

Historians estimate that more than 700,000 prospectors rushed the Klondike gold fields. This photo from 1898 shows miners filing over Chilkat Pass on their way to strike it rich. Farther to the west, prospectors took the Dalton Trail over Chilkat Pass for access to the Yukon interior.

On May 18, 1983, I was three days into a seven-day assignment with Alaska State Parks, which had contracted me to evaluate a remote area of southeast Alaska for remnants of the historic but long-abandoned Dalton Trail, which had been a trade route between Tlingit and Athabascan Native American people. In the late 1890s, however, the Klondike Gold Rush hit and approximately 100,000 prospectors poured into the region. A man named Jack Dalton began charging prospectors a toll to use the trail, which is 300 miles long and runs from Pyramid Harbor, west of Haines, Alaska, to Fort Selkirk on the Yukon River, upstream of the Klondike gold fields. During its brief, colorful existence, thousands of cattle, hundreds of horses and even a large herd of reindeer transported from Norway passed over this enigmatic wilderness trail in support of one of the last great gold rushes in history.

My career includes stints as a hunting guide, prospector and timber-faller in Alaska’s logging camps. I eventually made Master Hunting Guide, but the Dalton Trail assignment proved to be one of the most remarkable of my life, and I shared it with my wife, Carol, and state park employee Cynthia “CJ” Jones, as well as my dog, Kelsall.

Southeast Alaska has a dense population of coastal brown bears, and the investigation just happened to begin during their breeding season — a fact that complicated our efforts. I appreciated that serious defensive precautions were essential, especially since I’d met two Alaskans who had been seriously mauled by multiple bears.

I met Bruce Johnstone in 1977 while passing through Ketchikan en route to Haines to start a guiding business. Bruce was a retired woodsman, prospector and hunting guide, and he told several uplifting stories related to prospecting and guiding, but the impact of his bear-attack story left an indelible impression on me.

The Dalton Trail ran from Haines, Alaska, through the Chilkat Pass, then to Fort Selkirk on the Yukon River, upstream of the Klondike gold strike.

Bruce had been duck hunting, alone, at the mouth of the Unuk River in 1958 when he was attacked by a brown bear boar and sow with a two-year-old cub. During the unprovoked attack, be managed to blind the boar with a shotgun blast but was severely mauled by the sow, which went back and forth between Bruce and the enraged boar.

At one point, after getting knocked down and dragged about, he lost the shotgun in the water. When the sow returned to the boar, Bruce located the gun and killed the sow with a shot to the head.

The two-year old cub then started mauling Bruce, but his paper shotgun shells had gotten wet and swollen, and failed to feed into the mud-encrusted chamber. Bruce reached into his pocket with his only usable hand and grabbed what he thought was another shotgun shell. Instead, he latched onto a waterproof match container that jammed the action of his shotgun.

While sitting in water and covered in mud and his own blood, Bruce found a dry shell and managed to load the gun. He was saving the last shell for the enraged boar while striking at the cub with the shotgun barrel.

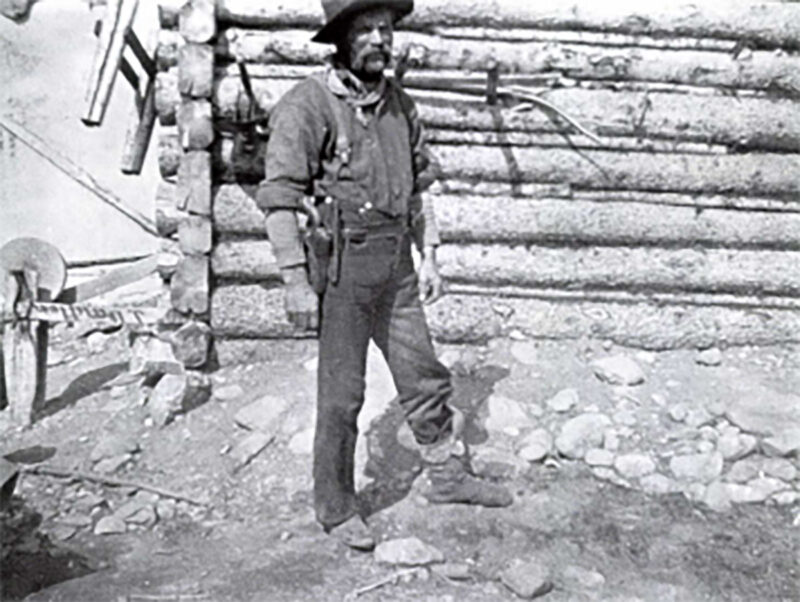

The Dalton Trail existed for years as a trade route between native tribes. Jack Dalton (pictured) took it over in the early 1890s and charged miners on the way to the Klondike for its use.

Another hunting guide just happened to be in the area and came to Bruce’s aid. He killed the large cub as well as the blind boar. He flushed Bruce’s wounds with whiskey to help prevent infection and got him to a hospital in Ketchikan.

Six years later, after living and guiding in the Haines area and just before our search for the Dalton Trail, I met Marty Cordes, who had been hunting with a man who’d been attacked by a bear. I asked him to tell the story to Carol and me.

Back in 1955 Marty had been hunting in the upper Chilkat Valley near Haines, Alaska, with his friend Forest Young, who’d returned alone to the site where they had killed a moose and left its hide hanging in a tree. As he neared the carcass, a brown bear sow with a cub attacked Young and mauled him repeatedly. The bear tore portions of his ribs completely from his body and had bitten through him to the point that his breath vented partly through his back. Eventually, the bears wandered off, basically leaving him for dead. In his extreme suffering, Young attempted but failed to end his life by cutting his wrists. Eventually, Marty found him, but Young was in no shape to be carried. Marty returned to Haines and brought back help, saving his friend’s life.

By the time we began our investigation, the Dalton trail had been abandoned for more than 80 years and only an occasional tree-blaze or vague pattern of rotted logs from portions of corduroy roadway remained to mark the passage of men. In practicality, the old-growth forest and lush vegetation of the Ciliate Valley had relegated the Dalton Trail to the history books. This meant we were destined to experience many of the same challenges the early explorers did while searching for the original route to construct their freight trail through the wilderness. But the atmosphere of the deep woods and the camaraderie of evening camps kept our spirits up and inspired conversations rich with historical facts about the Dalton Trail as well as our speculations concerning the camping methods of the gold-rush-era pioneers.

Despite all that, constant bear signs kept us on our toes. Fresh bear scat, with individual droppings the size of soda cans, provided a near constant reminder that we needed to exercise great caution.

We hoped we wouldn’t need firearms, but we had come prepared to defend ourselves. Carol carried a 44 Magnum pistol for close-up defense. CJ was armed with a 12-gauge shotgun, and during all phases of field work, I carried a bolt-action 458 Magnum rifle that contained three cartridges I had handloaded with 400-grain bullets. In my right-front pants pocket I carried three additional cartridges point down for efficiency of reloading.

We hoped we wouldn’t need firearms, but we had come prepared to defend ourselves. Carol carried a 44 Magnum pistol for close-up defense. CJ was armed with a 12-gauge shotgun, and during all phases of field work, I carried a bolt-action 458 Magnum rifle that contained three cartridges I had handloaded with 400-grain bullets. In my right-front pants pocket I carried three additional cartridges point down for efficiency of reloading.

One morning — after an early start, I temporarily got separated from Carol and CJ, and blissfully hiked through the forest with Kelsall trotting alongside. The pleasant morning and isolation from my companions freed my imagination to invite thoughts and speculations of times past to mingle with the present.

I imagined the prospectors with heavy woolen clothes, canvas-covered backpacks, oil-skin rainslickers and small, sheathed, single-bit axes strapped to their packs. In my search for history, I walked where pioneers had walked and imagined the hardships and hopes, crushed and fulfilled, they’d endured.

Then Carol yelled from the hillside above, breaking my reverie. She called out, “Al, you have a bear running at your back!”

I chambered a cartridge while turning, and at first I saw nothing unusual. Then, at a distance, a blond bear emerged from the timber and into our lives. It quickly cleared the top of an elevated windfall with a front-leg thrust and a powerful hind-leg kick that launched it airborne. It hit the mossy forest floor in perfect stride with eyes locked on me.

Then she yelled again, “There’s two!” And a second later, “There are three!”

As quickly as one bear cleared the log, the next one followed. I had no choice but to accept that three adult brown bears were simply hunting me as a pack of wolves would hunt a deer.

As quickly as one bear cleared the log, the next one followed. I had no choice but to accept that three adult brown bears were simply hunting me as a pack of wolves would hunt a deer.

Although not aware of the transition, my survival instinct had kicked in and altered my perception of time. My powers of observation moved to a keener awareness that turned time into a surreal, animated state of ultra-slow motion. The great enhancement of my mental acuity eliminated any thoughts of danger and attuned my focus solely on survival. My physical actions became automatic, immediate and precise.

The bears ran in single file about 30 feet apart, with heads held high and steady and their broad, muscular chests thrusting like those of galloping horses — and in the slow-motion of time, I could occasionally see each of their four feet off the ground in suspension of their gaits. Rolling waves of heavy muscles visibly rippled body-length under thick coats of shimmering fur as flashing claws and heavy feet hit the ground.

In the real-time of elapsed seconds after the bears vaulted the log, I yelled loudly and stomped my left foot forward into shooting position with each shout. I gauged the movements of all three animals while calculating when to stroke the trigger and weighing the consequences of my options. There were three bears, three people and only three cartridges in my rifle, so I was waiting until the last possible split-second to kill the nearest bear before it reached me.

My intention necessarily changed when the blond bear in the lead suddenly broke file a few yards out and bounded to my left, abruptly stopping within lunging range. I stood my ground as the second, a chocolate bear, halted a few feet in front of me while the third and darker bear darted to my right to disappear somewhere behind me. I remained motionless. The entire slow-motion event had actually gone from fast and furious to a gut-sinking dead stop in a few adrenalin-soaked, hammering heartbeats of real time.

After they stopped, the bears demonstrated no aggressiveness through vocalization or body language. I never saw them blink an eye, bare a tooth, or make a sound of any kind. They simply maintained alert carriages with unified and intense focus that projected their confidence and dominance over me.

For some reason, the chocolate bear commanded most of my attention. I had no choice but to trust my instincts, which told me it posed a greater danger than the blond. It stood very tall on four legs with its head held high, and when I matched its penetrating gaze the bear seemed to search my soul. Scant seconds of real time blossomed into additional detailing thought, and I noticed the neat patterns of fur on its face. The probing brown eyes and engaging countenance were eerily reminiscent of a young child’s innocent, frank demeanor.

For some reason, the chocolate bear commanded most of my attention. I had no choice but to trust my instincts, which told me it posed a greater danger than the blond. It stood very tall on four legs with its head held high, and when I matched its penetrating gaze the bear seemed to search my soul. Scant seconds of real time blossomed into additional detailing thought, and I noticed the neat patterns of fur on its face. The probing brown eyes and engaging countenance were eerily reminiscent of a young child’s innocent, frank demeanor.

Although I had little choice in the matter, I knew I could maintain some degree of control over this ultimate face-off as long as my strength did not falter and actions remained mistake free. The bears seemed to be anticipating an easy kill, but in my heightened state of consciousness, I experienced single-minded awareness and self-assured confidence — and I waited for them to make the next move.

A few brief seconds passed in stalemate as we intensely scrutinized each other — a brief study that supported my assumption that the chocolate bear dominated the scene. I kept my focus on him while maintaining a corner of my eye on the blond and my mind on the third, which not only remained out of sight but was the smallest of the three — and likely a breeding sow. I concluded that I stood between two rutting boars and a sow in heat.

The two males sustained their alert posture and unwavering eye contact — even as the chocolate bear took a tentative step slightly quartering from a head-on stance but toward me. The bear either expected that maneuver to prompt a reaction from me, or it was getting ready for a final assault. Regardless, getting even a little closer was a game changer, and I expected a lunge from the chocolate bear. I remained motionless with the rifle held across my chest and my eyes firmly locked into his.

Then he darted a glance at the larger blond bear to my left, and I looked at it too. In the same instant, its front feet left the ground in a low, flat lunge. The rifle touched my shoulder with what I perceived to be only a crisp snapping-sound.

The bullet’s 4,600 foot-pounds of energy exploded through the chocolate bear’s brain, down its spinal column and knocked the beast backward and down, instantly stone-dead, upright on its belly with powerless haunches gathered underneath. Its large muzzle fell tight against its massive chest, and blood streamed from the nostrils onto the ground as a gaping bullet hole under the right eye vented mist from the hot muzzle-blast.

I worked the bolt to load another cartridge, but the flat-nosed bullet jammed solid against the top edge of the chamber. The recoil had caused the magazine’s spring to slip forward and out of the grooved-stop in the bottom of the cartridge follower. I had played my ace in the hole to the best of my ability — but technical problems rendered my bolt action into a pure single shot.

I focused all my attention on clearing the action and inserting a cartridge directly into the chamber. In the realm of increased sensory perception, the muscle memories associated with loading the gun proved seamless in a slow motion of confidence that belied the urgency of the situation. When I did look up, I discovered that the other two bears had disappeared. One remarkable scene had flashed to another, and I felt instantly secure, with my dog standing quietly and firmly alongside.

Without even trying, the author found himself between this chocolate-color brown bear, another boar and a breeding sow.

Real time slowly resumed, and my visual focus and awareness expanded outward to normal levels of observation and perception. The transition to normalcy kept pace with the diminishing mental intensity — a slow fade that seemed audible, like the humming of a swarm of bees passing near, then into the distance.

The profound silence of the forest momentarily seemed foreign in its emptiness. It was as if nothing at all had actually happened — but before me laid the surprisingly out-of-place, hulking remnants of a once dominant bear that had materialized out of the mystery of the forest only to disappear from life altogether, just as quickly. I looked up the hillside to Carol and CJ and called for them to come down from their vantage point where they had wisely remained, undetected, quietly observing all that transpired.

We examined the dead bear in anti-climactic silence that bordered on disbelief. It was a mature coastal brown bear boar that weighed about 750 pounds and stretched nine feet long. He had been reveling in the zenith of life, rutting and invincible while traveling through the forest with two companions on a beautiful, blue-thriller spring-morning.

Although I felt no compassion for the dead bear, neither did I experience elation over his demise. There was no sense of conquest in viewing the ragged facial wound that intensified a desire to shift my gaze from the vacant stare of lifeless eyes. Rather, I felt deeply humbled by the fact that I was still alive and unscathed solely through the slimmest possible margins of luck and calculated chance.

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

Jake came to Alaska in 1967 and among other things, he holds Alaska Master Guide license #54, a commercial Pilot license, a 100Ton Mariner’s license, is a Benefactor Life member of the NRA and has operated from his eighty acre private land located 155 miles north of the Arctic Circle since 1969. Buy Now