When the old house was occupied, its splintering walls were stout, its diminutive shelter a fortress of good spirits, its heartwood hale and its ambiance light with ale.

Way long ago now, in the antediluvian and simplistic age in which I knew boyhood, circa. 1954, there was a song of considerable notoriety which folks came quickly to love called “This Ole House.” Written by Stuart Hamblen, and performed by Rosemary Clooney, it topped the music charts in that year both in the U.S. and U.K. An encore edition in 1981 by Shakin’ Stevens, altered slightly to “This [Old] House,” enjoyed similar acclaim.

Its immense and timeless appeal, which I could not understand and took more literally as a child, stems from its allegorical inferences to the twilight of life in an age—in any age—when a man’s body and being is intrinsically and sacredly likened to the structural and mindful shelter that houses his soul.

To witness, a poignant sample:

“This ole house is getting’ shaky,

This ole house is getting’ old,

This ole house lets in the rain,

This ole house lets in the cold.”

I still hold residence now, 77 years along, in the house of my birth. Renovated and appended across the years, by the state of my times. Be assured, the unplumbed figurative inferences of such lyrics are no longer arcane.

Under and upon the vast and epic Oregon sky and hills when the anniversary arrived, I was set upon by the phenomena such magnificent country brings: on the one hand, the overwhelming feeling of huge insignificance and vulnerability, on the other, an invincible and adventurous insurgency. In the youthful assertiveness that preceded seventy, before the shingles became less trustworthy—allowing a disrespectful degree of trepidation to rain through—the latter easily prevailed. Tie on a wild rag, fork a good horse and brave the blazes on with it.

God, those dogs look as gorgeous still, way out there, stacked up against the forever throw of those spectacular hills. Though the drama in the prevailing and fathomless sky somehow looms a bit more foreboding than ever it has before.

Now, when more occasionally I am forced to examine the roof to question should it last a few years longer, disconcerting prickles of light steal through, and the answer is more precarious than I remember before.

“This old house once rang with laughter,

This old house heard many shouts,

Now it trembles in the darkness,

When the lightning walks about.”

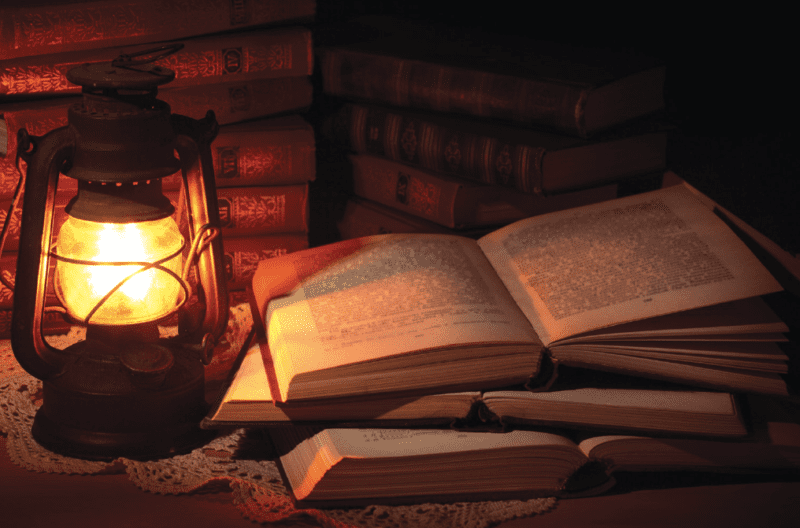

In the yellow lantern light of elk camp on the same trip, my companions in arms offered alms to my continued health and happiness, I to theirs, heartily sang to me, and for a while the timbers no longer sagged, the laughter was renewed. Until an hour later, in the protective cocoon of the sleeping bag that evening, the wind moaned my eaves, and I could feel the foundation tremble slightly above unstable ground. Will the sleepers hold, the floor remain solid, the foundation stand strong, for the remainder of the shorter days, now, to come?

There are days I think so. There are days I fear not. I no longer laugh when lightning walks about.

I do not wish to leave what has been this wild and wondrous place, nor vacate the house of the man who has dwelled in it, though it now be evermore weathered and worn, until my river has fairly run to its sea.

But what in a man’s life is fair? I walk by the small cabin on the hill, in which a friend once lived, and laughed, and loved. He left too soon, sooner than the length of my years. The little house is empty now, forlorn and failing, uncared for and overgrown with creeper, willed to the worst. In a few years, it will again be no more, become a part of the earth from whence it came, the rocks of its foundation becoming only anonymous stones in a nameless field.

Though when it was occupied, its splintering walls were stout, its diminutive shelter a fortress of good spirits, its heartwood hale and its ambiance light with ale.

I remember the afternoon when snow came, when after a quail hunt we ensconced there, cold and wet, stoked up the little pot-bellied stove, retired to the couch, the dogs on our laps, steam rising from all. Jim was happy in his house, and I in mine, and who would have known then…or cared to know…that all the time one of them was so rapidly decaying. Gladness had it at bay, we never wondered.

One by one, the boards fall away, the roof caves in, and the bones shine through. Sleepers, timbers, joists, rafters and purloins, the framework that houses a man’s life, protrude starkly naked and askew. Ordered and plumb while still he was here, left lonely and forsaken when the day comes he is gone.

People try to console me. In their presence, I have learned you can be lonely even when you are not alone.

I live under the roof now of a rambling and vintage old sporting lodge, surviving from the early twentieth century. Architecturally archaic, and antiquated in style and design. The house in which I am happiest. I look around, do not wish it to be renovated. I find no habitation within a contemporary penthouse overlooking “Times Square,” a black rifle in the corner with a laser on a Picatinny rail. On every wall hangs the images, in form and facsimile, recent and faded, of a life at sport well-lived. Of a life at sport well loved. Of a life that has rambled through wildness and adventure, and at least for now, is at home and at rest again. In the house that still shelters my soul, and welcomes it home. Not the one I was born in, but that I built of my own.

But the lanterns that burn constantly light only the main hall. They flicker uncertainly when the wind sifts through evermore fragile walls. Every day sooner now they will be extinguished too.

There are only two rooms of all the many where the doors remain ajar, the oil lamps lit: the library that shelves the volumes of my years, and the museum that accessions the talismen of my trails. For I am drawn more often, to visit and bide in both. I read the remembrances of others, append to them my own, and hold to heart and hand fondly again the things I especially love.

The others, the 18 that were structurally added across the eclectic eras of my magnanimously-blessed years when still I was building and the foundation stood unshivering beneath the load—are closed now. The doors are locked and time has lost the keys. I can transgress their sanctity only by the skeleton key of memory. Every board, every nail, carries a memory.

Of days and dogs, of mountains and hollows, of rivers and rills, of tumbling brooks and thunderous waterfalls, of fish and fowl, of elk and deer and bear and sheep, of countries and continents, of miles and moments, friends then and friends gone, the days and ways we spent, given together to wildness.

I cannot go back. I can only go forward. The light at the horizon is no longer as bright, has fallen on some days uncomfortably dim. But how infinitely thankful I am, that this old house, weathered and gray, still stands. This old house that has withstood storms, launched countless adventures, housed a life that only an infinitely small percentage of people on this ragged earth ever are blessed to know.

That this old house still is here to invite and welcome my deeply cherished friends of the present, to house on its walls the faces of those I loved that are gone, to enshrine a chapel of soulful reverence ever thankful that for now, all shivers on strong.

Some days I’m afraid. Some days I’m bold. Some days I leave almost as confidently as always I did, return as I will, and, like when, thrill again to home.

The house still stands. Yours and mine.

Many of you have told me so, in words and manner. From my house to yours, I love the time we spend as one on these pages. We built well. We are alone together. It is wishful to think of 106, given we can still climb the elephant.

Even if, one day sooner now, you and I both know,

“Ain’t gonna need this house much longer,

Ain’t gonna need this house no more,

’Cause I can see an angel peepin’,

Through a broken window pane.”

Well, hell. Pray please, we’ll have a while yet to fix the damn thing before we go.

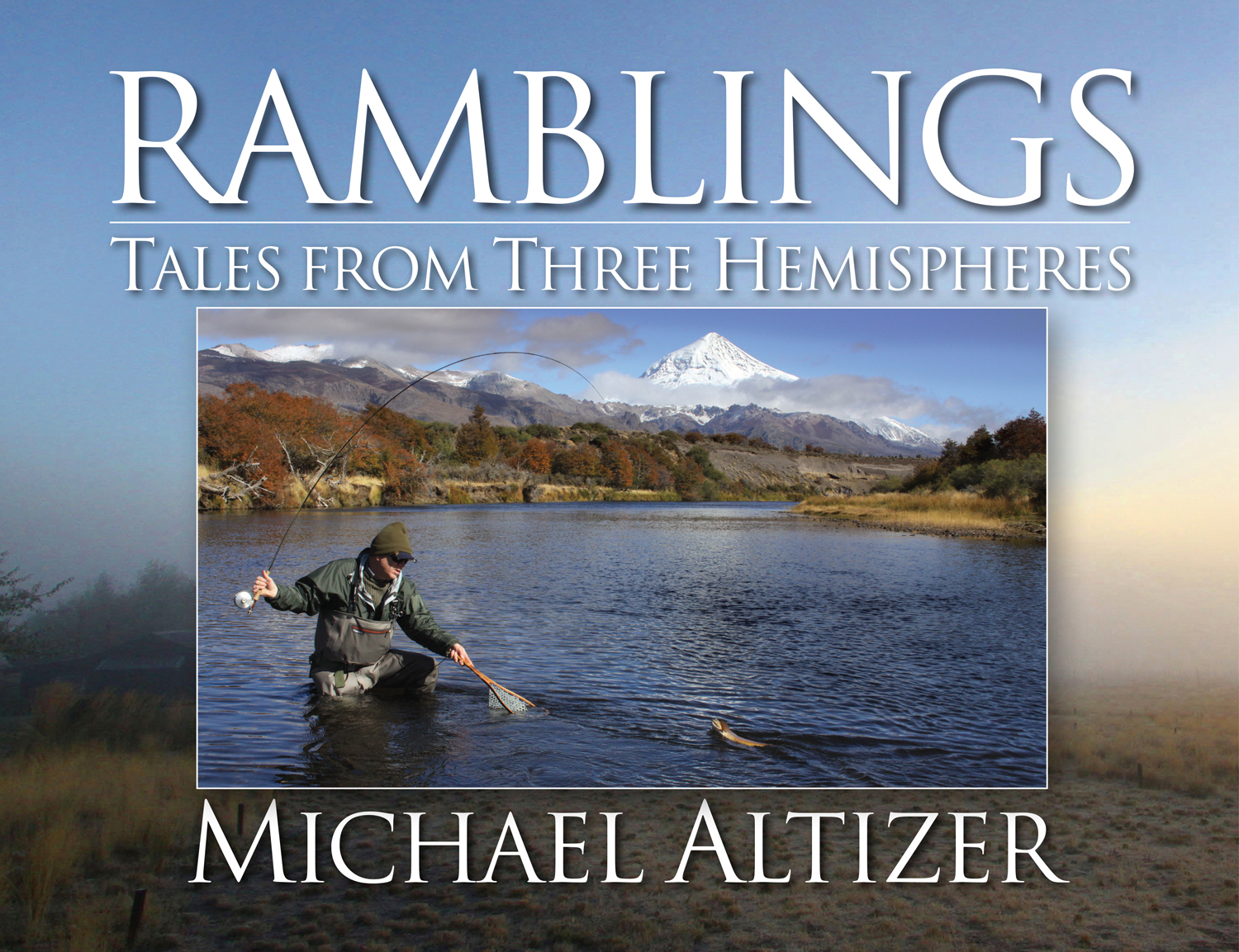

This beautiful 240-page tabletop volume contains 189 lush black-and-white and duotone photographs, paintings, and drawings that richly document the author’s contemplative and intimately composed accounts of his hunting and fishing journeys, from Patagonia to Alaska—along with the guns, fly rods, bows and friends with whom he shared the adventures. Buy Now

This beautiful 240-page tabletop volume contains 189 lush black-and-white and duotone photographs, paintings, and drawings that richly document the author’s contemplative and intimately composed accounts of his hunting and fishing journeys, from Patagonia to Alaska—along with the guns, fly rods, bows and friends with whom he shared the adventures. Buy Now