South Carolina’s Daniel Island is actually a peninsula of the original Cainhoy Plantation sandwiched by the Cooper and Wando rivers that probe southward into Charleston Harbor.

I like living here for a lot of reasons, and one of the big ones is clean access to inland saltwater—from docks, marsh points, walking trails and boat ramps. One of the docks is more like a small river pier, and it typically attracts a handful of folks every day year-round. I use it as a testing ground for new lures, as a quick-fix trout spot, an ideal place to take my two-year-old son to watch fiddler crabs and container ships, and as a venue to unwind and breathe after long workdays.

After work yesterday, I grabbed a trout rod and new suspending Mirrolure and shuffled down to the island pier. Because of a stiff breeze and the dock height, I turned my rod upside down and held it in my right hand like a fork—thumb and forefinger hooked around the reel seat, tip down closer to the water. The river was tannin-stained, but clear, and I could see the little shad-shaped bait dancing and pausing below me in the tide.

Suddenly a trout flashed on it, then swiped at it again, and I chuckled as the little male fish kept drawing up behind the lure until he finally whacked it. I played him subtly and looked around at my neighbors—a guy my age floating a mud minnow, an older lady tending crab lines and a feather-son team chunking double-rigged shrimp into the void, hoping for bites.

The mud minnow floater spoke up when I flopped the little speck.

“Hey man, I’ve never seen anyone hold a rod like that!”

“Yeah,” I responded, “I guess it’s left over from my old pier fishing days.”

I realized my response was lacking, so I just kept going.

“Used to Spanish fish like this, with the old Gotcha plugs,” I hollered over the wind. “Easier on the arms!”

“Gotcha,” he said, grinning, nodding, and I wasn’t sure what part he understood.

The trout was just big enough to keep, but I was in office clothes, in a hurry to pick up my little man from daycare, and so I thought better of bringing it home. But something made me lay it down on the planks anyway, flick the plug into the current again, and repeat the routine on three or four casts. In the lull, I watched the crab lady switch the cotton line toward her, one inch at a time, then ease a jimmy crab into her drop net.

A fish ticked my plug while I watched her and I managed to land another one. With a 17-inch trout in each hand, I walked down to the father-son team and offered them dinner. In a split second, I had a new pair of friends and a small audience checking out the shiny little plug on my leader.

”Y’all enjoy ’em … gotta run,” I said, checking the time on my phone as a flood of smells, sounds and memories followed me off the pier. Creosote and seaweed dried to wood planks, clam and crab-filtered air—sweet and rotten all at once, a few late laughing gulls sounding off and the unexpected conversation between different walks of life. As I drove to get Hunter, my mind drifted much further.

I grew up fishing on Oak Island in Brunswick County, North Carolina. Before johnboats and driver’s licenses I had to invent ways to fish from the hill. We learned soon enough that when all else failed, there was always the pier. Clearly, the three island fishing piers offered the most surface area and the longest jut into the salty maw, but the closest one was exactly 1.91 miles from our creek house. Dad introduced me to fishing, and we fished from old ski boats, tin boats, in the surf and off docks of all kinds. But he actually introduced me to the piers when we weren’t fishing at all.

The memories blur together, but I remember an afternoon in the fall – probably October or November-Dad and my granddad taking me to the local oyster and beer dive, which was called, uncompromisingly, the Oar House. It was perched at the foot of the Yaupon Beach Pier.

First, this meant rattling pans going by loaded with steaming clusters. A hole in the table for shells, a bucket under the hole and a menu on the wall made of a toilet seat that opened with a pull cord. The walls were plastered with dollar bills and bras and the classic hodgepodge of mess that excites any young, wide-eyed boy. And while we waited on our orders, we took long walks down the hulking wooden highway that pointed southeast into the ocean.

“Can we go walk the pier, Dad?”

“Sure son, let’s do it.”

There was also a family friendly restaurant one layer back from the Oar House, and on other occasions, the whole family would go eat there and take those same walks, spring, summer and up to Thanksgiving. As you might imagine, I looked in every bucket, watched every cast and hook-set, probably asked more questions than I got answers.

Most of the distinct memories are clipped – a giant flounder curled in the cleaning sink, the first doormat I’d ever seen. A group of guys frantically bombing and jerking weighted rows of treble hooks to snag menhaden for king mackerel bait. Dried shrimp tails and empty Budweiser cans, cigarette smoke and turpentine, the barnacled breath of pier life swirling on a prevailing southwest breeze.

One man was way out on the pier head, waiting for a king to pick up his pogy while another was a quarter-mile inland, rod pointed down at the surf curl, bouncing a finger mullet along the sand. There was hollering and the roar and whisper of surf, reels and pier-cart wheels squeaking and clicking in different time. The pier was a symphony moving in a rhythm all its own. After dinner, with full bellies, we’d walk it again.

At some point I got permission to go to Yaupon on my own. Now, 1.91 miles may not sound like much, but on foot with a metal wagon full of minnow buckets, cast net, rods and tackle box, it was a haul. I would knock out the first leg in a straight line down two streets and across the main road until I hit sand, then turn east and drag my rig down the beach. Eventually, I would have my ticket and get set right beside the cleaning table and sink, finding my bench and the notches in the wood rail to lean my rods, emulating the same men I’d watched so many times before and after dinner. It was almost always about flounder for me, with trout, Spanish, blues and kings as side bets when they were running.

I did what the old floundermen did, walked slowly and dragged my bait up and down the pilings, starting at the surf and working my way out. I dreamed of hooking a big doormat, dragging him up on the beach maybe, or landing him with one of the old timer’s dropnets. I would put him in a white bucket, with the tail flopping out like a big hand, and I’d roll him back home to the family. We’d eat him stuffed with crabmeat or fried in a skillet with flour and lard, like Ruark’s Old Man would do.

I began to meet the old guys and talk to them, and they eventually seemed to accept me. I kept a journal, too, with everything from tides to chicken scratch notes from conversations.

I fished with Bill Osteen, a retired electrician who spent his early mornings on the pier and stuck around if the action was good. Mostly he told me he was escaping honey-do lists and spending time with the other pier regulars. I didn’t know what honey-do lists were, but I laughed anyway.

I remember watching the trout guys and learned from them how to rig slip-corks. A man from the freshwater creeks of North Wilkesboro named Ralph Jolly would always let the orange cork stay under a second longer than I ever could before setting the hook. After lowering the drop net and landing the fish, he’d grin and slip the fish into his cooler.

“That’n was only sixteen inches,” he said with a slow twang, pinning another live shrimp and launching the rig over the rail. “He’d a been a big’n if he’d a been at the spillway back home.” He told me that he and his wife spent half the year on Oak Island, and their season tickets stapled and overlapping on their hat bills attested to their love of the pier.

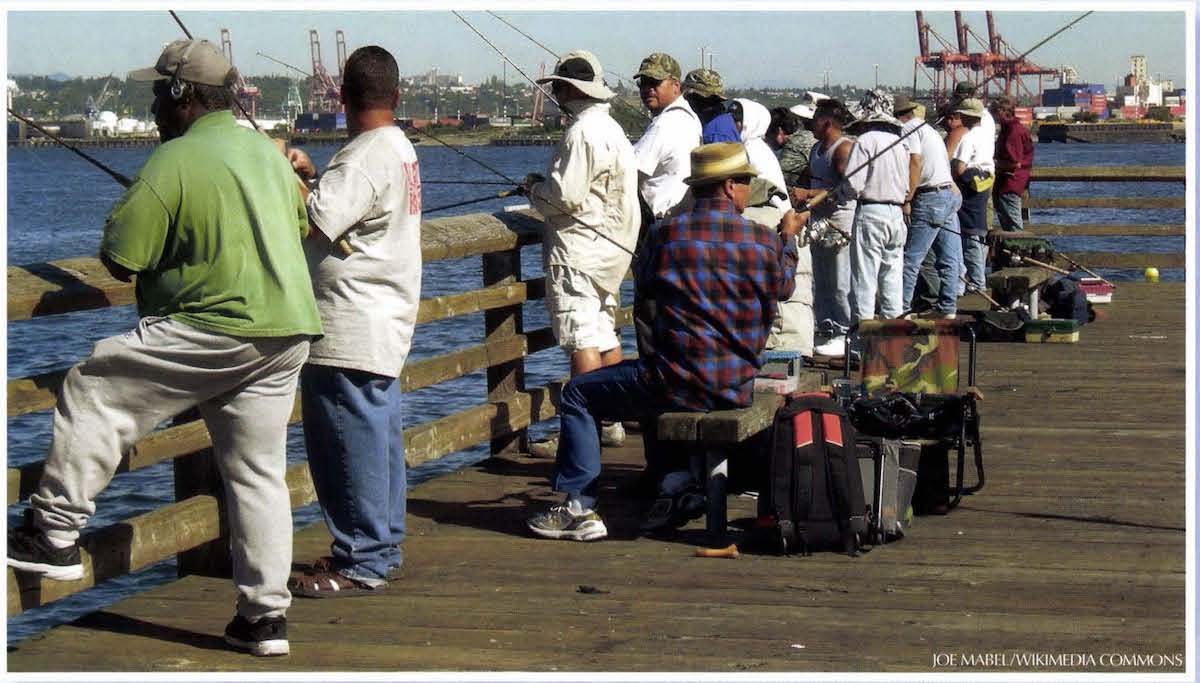

There was always the wide-eyed excitement of weekenders. A passing fleet of stingrays or shrimp trawlers, a school of dolphin or a half-pound pinfish could make someone’s day on the pier. It was the perfect place to start – the place to learn the basics and everything in between. But when the fish were running, everyone got serious, weekend anglers and locals alike. They lined the rails shoulder to shoulder, no room for secrets, and the Spanish, blues, trout and kings thrashed below.

Camaraderie abounded among the locals, often gathered like an early morning breakfast crowd at the end of the pier around the king mackerel rigs. Together, every day, they waited for the big bite, knowing they may go for a week without a strike. They joked about tourists and grumbled over stingrays and shrimpers, but often jumped at the opportunity to teach a casting lesson to a youngster. Their tools of the trade – carts, umbrellas, coolers, rods and live wells – were critical in daylong battles with fish and heat.

The pier cart was clearly an essential item for that long, elevated path above the sea. Loaded with every size rod for every possible fishing scenario, iced down with drinks and fish, creaking and humming and gurgling their aerators, these vehicles were their owner’s signatures. The carts ranged from red Radio Flyers like mine to rusted recycled grocery buggies with plenty of personal touch.

I remember one day when I was buying my ticket at the Yaupon Pier desk from the clerk, I asked her who had the best fishing advice, and she replied without hesitation, “Mr. Paul, and he’s got the best cart, too.” So I got to know Paul Hales, ever recognizable in a stark white foam-and-mesh ball cap perched high on his head who carried a drop net, king rods, trout and flounder spinners, giant coolers, bait buckets and all essential terminal tackle on his customized grocery cart.

Mr. Paul always caught the first big king of the season and consistently did early morning damage on the speckled trout. Since he didn’t venture out in his boats anymore, he decided to perfect the art of pier fishing. I knew from the first minute I met him that Mr. Paul had landed that monster doormat flounder I’d seen in the sink when I was younger.

“It’s a challenge, fishing out here,” he told me one day. “You’ve got to find the fish and have the right rig. I study fishing because I like things to be just right, and some people out on the pier have followed my lead; like this cork rig for trout right here, for instance. I was one of the first to start using it.”

Ray McGinnis had fished Yaupon Pier for a long time, and I probably stuck closest to Ray and Mr. Paul. He told me he averaged 300 days a year on the pier; he had harsh words for the shrimp trawlers combing along close to the beach.

“You need to remember, son, one day there won’t be any fish to catch if they don’t move these trawlers off,” Mr. Ray would say.

One day Mom and Dad brought the whole crew out to check on me and right then I felt a good thump on the mud minnow. I rared back on my rod and unknowingly lit a fire that’s still burning. It’s honestly still hard for me to tell this story today.

So the whole family had gathered round – grandmother, mom, sister looking in my wagon, my buckets, asking me how I was doing and so on. Picture a skinny, sunburned 13-year-old boy who wants nothing more than to catch his first real flounder on his own, clearly wanting nothing to do with this scene. I waited, but not long enough, and set the hook on something pretty heavy. I remember looking over and down the taut line – so incredibly far down – and seeing that brown creature connected to my rig, easing along under the surface.

“Get a net!” I yelled, but there were none around. Hadn’t crossed that bridge yet.

“Look at that flounder!” someone else hollered as I decided to commit and began to crank.

Bracing the rod against the rail, I commenced to reeling the keeper flounder up out of the water, steady grinding him through the air in a slow spin like a basket into a helicopter. To be clear, this was maybe a 17-inch fish – a two-pounder at best – but it was to be a huge fishing milestone for me. Biggest flounder, from the pier, caught completely on my own. Instead of wheeling the fish home for the driveway-reveal, it was happening right then with everyone as witness. The fish was halfway up the pier.

You know what happens next.

After a smooth fight, easy glide to the surface, and calm path up through the mollusk-tinged air, that evil brown placemat came to life. He opened his gills and gill plates and shook like a Jack Russell trying to kill a cotton squirrel. One violent shudder is all it took as I frantically reeled the empty hook away from the back-flipping fish until he smacked the sea with a sound I can still hear. I very literally cried, and I was not fun to be around for a good while. At the time, I didn’t know that I’d be standing at that same sink with a much different attitude in the years to come.

Four years later, after convincing our dads that we could clam and fish for summer jobs, my best friend Matt and I began to ply the river for good flounder spots in his 16-foot john boat. We struggled to produce from the boat, still getting out all the kinks and learning what gear we needed and didn’t need. We had a tight budget, and every detail had its learning curve – anchoring in current, running back-channels around oyster rocks, keeping cast nets, bait nets and landing nets in working order. That’s when another pier came into play just in time.

Back home, one of my junior high pals named David Rotan had mentioned something about catching flounder off their pier at the Fort Caswell Baptist Assembly on the western point of the gated Civil War fort on Caswell Beach. Caswell was one beach down from Yaupon on Oak Island, mere minutes from my creek shack.

Skeptical but interested, I put in an open self-invitation, and when the Morganton First Baptist van arrived that summer, I got the call. Again, some of those moments split and merge, but suffice it to say we took full advantage of the situation.

We started off joining David to fish. Then we figured out how to sneak in the guard gate by hiding in the back of Mom’s station wagon when she drove through. We hunkered down with our gear, the whole mound covered in blankets while she got a guest pass, drove in and dropped us off.

Matt and I both remember two people in particular who frequented Caswell. A man in his 70s named Avery meticulously worked four rods that he’d cast into four distinct spots. He described the structure and tide and current in each of those spots. He always caught a few nice fish, and slowly scaled and filleted them in the sink, talking and teaching as he went.

A lady with mahogany skin who was draped in a floppy hat and plaid cotton shirt walked up and down the pier with a short, antique conventional rod and reel suited for grouper. She typically used giant bait – picture a seven-inch hardhead mullet – and she’d often reuse the bait after landing a fish, dropping it straight back down right beside the cleaning table sink. The beasts she docked are still legendary with Matt and me, but I remember one particular afternoon, post thunderstorm, when we were scrambling to catch bait down on the beach below the pier. She landed fish after fish, doormat upon doormat on the same ragged mullet. I helped her usher at least two of them onto the beach, and both were seven pounds or better. Slabs. Forever, in our annals, the Flounder Lady.

We fell in behind both of them, catching finger mullet in the river flats and filling yellow buckets with them, casting single-hook rigs into the heavy current and sunken Civil War rubble, and landing a few nice fish. Once, Matt lost a three-pounder at the water’s edge, and we watched the fish settle into the sand with his head still out of the water. Matt jumped on the railing and did his best Animal House Jim Belushi -looked left, looked right, looked left again, looked down and jumped. A long way down to the sand, painful grunt and roll before shuffling up behind the flounder and tossing him onto dry ground. And as we fished and got better, we attracted just enough attention to alert the Baptist authorities.

Once the guards and camp director figured us out, we switched to pulling our boat up on the river beach beside the pier and walking up to fish. There was just something about being still on that pier, something that made us safer, more patient and surer of ourselves. We had a sink and table to clean our fish. We had confidence, and we understood the angles – which I’ve since learned are perhaps the two most important aspects of fishing.

Avery and the Flounder Lady didn’t mind us up there at all, but the “Caswellians” finally had enough of us and banned us for life. So we took to anchoring nearby and figured out how to catch them from the boat. And, in a time long before crowded fishing holes, GPS units, Google Earth and the Internet’s fishing forums , we had a fine run in that river and carried home some heavy coolers.

Maybe it was just logic that led us back to the Yaupon Pier sink to clean those fish, or maybe it was just one of those weird moments when fishing comes full circle. Whatever it was, that’s where we ended up carrying our cooler after we’d trailer out of the river. It was usually hot and dark at filleting time, so the old pier offered lights, hose water, a well-worn cleaning surface and a good breeze. Tourists and locals always crowded around, and we’d wearily look up from our knives to answer questions.

“Did you catch ’em here?” The excited weekender would ask.

“I know you didn’t catch them fish here,” the obvious local would proclaim.

“What are those?” the tourist would wonder.

“What’d you catch ’em on?” someone else queried.

I didn’t look up, drawing the blade along an opaque skeleton and peeling back thick white fillets.

“Cut bait,” I said.

“Cut bait, sheeit,” the old man said smiling from under his tall white cap and walking his loaded cart down the pier into the dark.

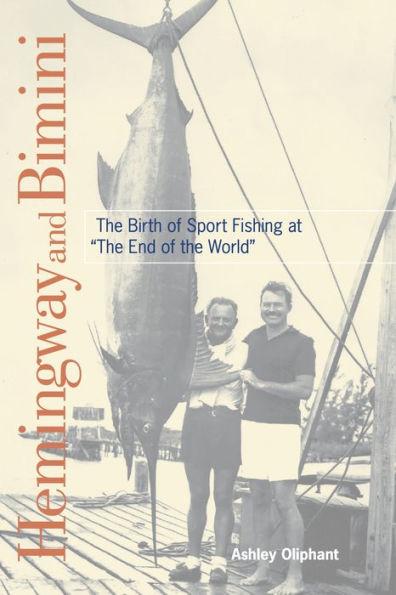

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his underappreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his underappreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

This is the only book on this period in Hemingway’s life and reveals unexpected dimensions to the Hemingway portrait that deserve attention, including his surprising humor, his advanced conservationist views several decades before the environmental movement even began, and his egalitarian ideas about his contemporary female counterparts in the big-game fishing world—challenging the usual portrait of Hemingway as a chauvinist with no personal rules, boundaries, or conscience. Includes beautiful vintage photographs of 1930s Bimini that have never been published in book form. Buy Now