From the 2014 November/December issue of Sporting Classics.

Joe Maffo got his ass in a sling when he turned Big Al loose. Big Al was a gator, well known hereabouts and a robust specimen, a dozen feet and a thousand pounds. Big Al peaceably prospered on a ration of turtles, fish, coons and the occasional lapdog, but he got lonesome and took to roaming and he plugged up traffic on Lagoon Road. You just can’t plug up traffic in a tourist town.

Got a half-ton of resolute gator across two lanes, impeding passage of Priuses, eco-friendly Hondas and Subarus Made with Love? Who you gonna call? Call Joe Maffo.

Buzzards on the balcony, hogs in the hallway, copperheads in the couch, possums in the pantry?

Call Joe.

Big Al was the biggest gator Joe had ever seen, and he just couldn’t kill him, though the law said he must. Couple days previous, a ten-footer came up through the surf on Folly Beach and scared the beer right out of a crowd of college kids down for spring break who initially thought a log had washed ashore. The law called a gator wrangler who popped it in the head with a 357 in full view of the assembled bikinis. You would hardly think a gator could elicit such sympathy, but there was much weeping and wailing at the scene and a subsequent perfect storm of outrage in the press. Joe Maffo took note and when he got Big Al winched onto a flatbed trailer, he backed down the boat landing and loosed him into Broad Creek.

But Big Al did not take to his new home. Ten days later he was roaming around again, snarling traffic in the middle of the afternoon. So Joe Maffo wrassled him down a second time, hauled him clean up to Jasper County and loosed him on the New River, much to the dismay of the Jasperites, who reckoned they had their quota of gators already.

“I’d a caught hell for killing him,” Joe mused. “Now I am catching hell for turning him a-loose.”

Wrasslin down a gator? Ben Moise, 27 years as a warden along the Santee, tells how he did it. “I went equipped with half-inch braided nylon line, a long pole, a roll of duct tape and a bag of marshmallows.”

Marshmallows? That’s right. This ain’t your ordinary story.

“To entice the beast into range, we’d cast marshmallows upon the waters. They’re known to be a favorite food of alligators due to their resemblance to golf balls. As the gator neared the closest of the white nuggets, we’d slip a noose over its head and snatch it tight. Then all hell would break loose.

“To entice the beast into range, we’d cast marshmallows upon the waters. They’re known to be a favorite food of alligators due to their resemblance to golf balls.”

“I’d drag that old gator up the bank and tie him close to a tree. Then I fixed another noose and slipped it over his tail and drug it around and pulled it tight around another tree until he was in a stiff straight line. Only then could you crawl up his back and grab his jaws and tape them together and tape his eyes shut and tie his legs behind his back and fling him into the pickup.

“The worst part was turning him loose. He was roaring mad by then. If it was a big gator, I usually attracted a helpful crowd. There was no way to predict which direction the gator was going to head when freed of restraints, which led to some extremely amusing stampedes.”

The big predators were about wore down to nothing in the ’60s, when gator belts, boots and wallets were all the rage and the skins fetched ten dollars a running foot. The Jasperites hunted them with flashlights taped to the end of 22 gun-barrels, and the law couldn’t keep up with the poaching. But the 1973 Endangered Species Act killed the market for the hides, and the Jasperites went back to making moonshine and growing marijuana and they were good at both.

You could still take a pesky gator with permission, like Phillip Buckles did when one snatched his retriever right off his front porch just as he was sitting down to supper. He baited a shark hook with a freezer-burnt pork shoulder and chained it to a cypress stump. He had a gator the next morning and the stomach yielded hardware from seven dog collars—but none his.

There’s probably a hundred-thousand gators now, plenty thick enough to hunt. Joe Maffo and his cohorts typically snag 300 to 400 each year, and the state issues a thousand-plus tags via a lottery at a hundred bucks apiece.

Gator meat is mighty good, good enough to make a factory-farm frying chicken hang its head in shame. But then, there is the fine print. You can’t shoot a gator unless you get a line on him first. Lasso, snare, harpoon, arrow, or treble hook, the Law does not care. But you snag him somehow, haul him to the side of your boat under extreme protest, and you shoot straight down with a revolver or bang stick. And if you fire the bangstick above water, you are apt to be wounded by flying meat and bone. Surviving all, you suddenly have several hundred pounds of gator meat to cool off quick.

The official gubmint gator guide contains a final caution: “Never assume any alligator is dead.”

It’s a God’s wonder anybody would do it but they do, and they line up for the chance.

I’ve been around here a good long time and I’ve seen my share of gnawing. The golfer who lost a ball and then an arm when he tried to retrieve it. The jogger mauled when she got too close to a nest. A tug of war, a boy on one end, a gator on the other, his momma in the middle. The man who flipped a tractor into the pond and by the time he got himself untangled, the tractor was the least of his worries. The burglar on the run whose final bad idea was to take a short cut through the cattails.

Just no end to it. Bass fishermen catch particular hell. Phil the Bug Man was tearing up four-pound largemouths when he noticed a baby gator angling for a fish. The gator was about the size of the fish, and the Bug Man gave it a jab with the end of his Ugly Stick. The gator went eeka-eeka-click-click like baby gators do, and the water erupted in a mighty froth as momma gator launched herself upon the dock. She got her head under the railing but her front shoulders hung up. She thrashed and snapped, then fell back overboard. The Bug Man was recovering pulse and sphincter when he heard a rustling in the canes. Momma Gator was sneaking up the bank, trying to get between him and his truck. It almost worked.

Terri’s brother Terry was fishing bass too till he ran out of beer. He knocked on my door. “You got any Bud, Bub?”

“No, but I got couple bottles of Corona.”

“No Bud in the can?”

“Nope.”

“Well, I’ll take the Corona then.”

An hour later, rod in one hand, Corona in the other, a gator made a snatch at him. He dropped the rod but not the beer. He turned to run but slipped and fell. The gator was on top of him in an instant, and Terry commenced to wear that gator out with the Corona bottle. Taken aback by a dozen whacks, the gator repented and relented, and Terry showed back up at my place with mud and scratches sufficient to allay disbelief.

“Now ain’t you glad,” I asked, “I didn’t have no Bud in cans?”

I had my share of rodeos too, necessitating an occasional change of skivvies but never medical attention. I tried to shoot a middling gator off my dog with a Smith and Wesson 38, but the hammer spur hung up in my jeans and I been toting shrouded hammers ever since.

I had a bull come at me in the New River marsh, not far from where Joe Maffo sprung Big Al. Burrup, burrup, he said, like a giant toothy bullfrog, like a chainsaw out of gas. And then the juncus cane started moving like the wake from a torpedo. I couldn’t see my own feet much less that gator, but I slipped the safety and got ready to shoot, even if it were between my knees. The gator had second thoughts about two seconds and ten feet out, passed me in a great rush and plunged into the creek. I never saw him but judged him full grown by the splash he made.

Thanks to micro-chips and satellite tracking, we know a lot more about gators than we used to, maybe more than we want to. Dipping in the ocean or a salt creek? Keep your eyes peeled. They’re out there too.

If you ever thought you could get shut of a gator by climbing a tree, forget it. Given motive and opportunity, a gator can climb any tree you can. Fence your yard with chain link? A gator can climb that too. Gators have been known to get up on a front porch and ring the doorbell, but micro-chips and satellites can’t explain that. Neither can I. And no, I ain’t making any of this up.

And they home, just like pigeons. Years ago my Jasperite Cousin Jack wrangled a dozen or so, hauled them halfway to Charleston and turned them loose. Two weeks later, that big female missing the first toe on her left hind foot was right back where they trapped her. A long distance of 40 miles, half of it across deep saltwater with a four-knot tide. Figure that out in your spare time.

And it gets better. Once they fitted a few big ’uns with trackers, scientists noted homing gators ran the compass rather than taking the easy route. Points, islands, parking lots—didn’t matter. Like migrating birds, they were headed home.

Down at the beer joint, Cadillac James is working the bar and Wendell is bending the guitar strings. We call him Cadillac from his ’85 lemon-yellow Coupe de Ville. He’s a mighty fine barkeep, remembers your name, what you like to eat and drink, and he is fine company when not too busy. Wendell drifted down from the Tennessee high country to lay low, write songs, and pick up tips and maybe a girl or two. He’s among the legion of fine song-writers the South has raised but struggles to support. A shrimp boat of dope coming ashore on the new moon, a pickup wreck on a lonesome pinewoods road, a ghost on the beach at midnight? Wendell has it covered. He’ll wait tables if he has to, tend bar too so long as he can still make his music.

“Whiskey and water?” Cadillac asks.

“Baptize ’em, don’t drown ’em,”

I reply.

I catch Wendell’s eye. He smiles and nods and breaks into a new song.

There’s a mean ol gator comin’

round again,

He’s a twelve footer in the pond

behind the inn.

You joggers and jigglers and

Jaspers beware,

Don’t wander off the trail if

you’re going down there.

Then he picks a jazzy bridge and takes up the next verse.

Me and Frankie Nash

Found a way to make some cash,

Sellin’ gator skin up in the hood

Po ol Frank

Slipped down the bank,

The gator got him good,

Now his leg is made of wood.

“You hungry?” Cadillac asks. How ’bout some gator bites?”

“They any good?”

“Make your tongue beat your brains out.”

“You got any honey mustard?”

Cadillac pours my whiskey and the sun slips off toward Savannah, across the vast spartina grass flats, the little side creeks and backwater ponds glistening like a shattered mirror of the sky. Fourteen miles and Lord knows how many gators away, the domes and spires of that beautiful and tragic city catch the slanting light and glow like some Pentecostal vision of the New Jerusalem.

And Wendell breaks into another verse:

Mr. Roy Lincoln

Took to brown likker drinkin’.

Kept a bottle hid behind

the fence.

He went to take a drink,

Fell in the creek.

Gator heard the splash,

Roy ain’t coming back.

The tide rises to brimming full and the wind drops to a whisper at the tide change. Then way off in the marsh I hear it—burrup-burrup. Maybe it’s just a heron. But maybe it’s Big Al coming home. +++

Note: Pinckney’s latest novel, Blow the Man Down and Ben Moise’s tell-all memoir, Ramblings of a Lowcountry Game Warden, are available on Amazon. Wendell’s music videos, including “Mean Ol’ Gator,” are on Youtube.

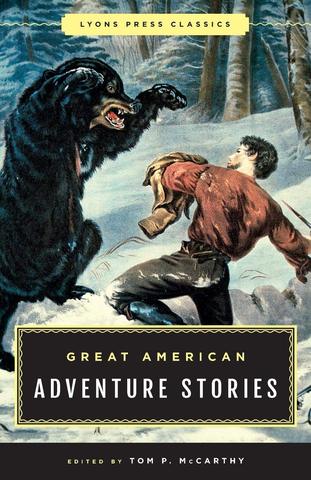

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now