Whatever the goal, the safari became a recipe for disaster.

The great elephant rounded a clump of acacia and swung toward the two hunters. Drying blood made dark stains down its wrinkled shoulder and neck, but despite its wounds, the big animal moved deceptively fast with that ambling gait that makes you misjudge its speed.

“Wait,” the African veteran whispered.

The elephant rushed toward them — then, abruptly it stopped, backed several steps. Its ears came forward, moved like fans, listening for them. Hot, tiny eyes were red with hatred. It came again with a rush, only a couple of strides, backed away, rushed again.

The trunk went straight up, and the big male elephant screamed.

“Shoot!,” the veteran cried, knowing the charge was coming now.

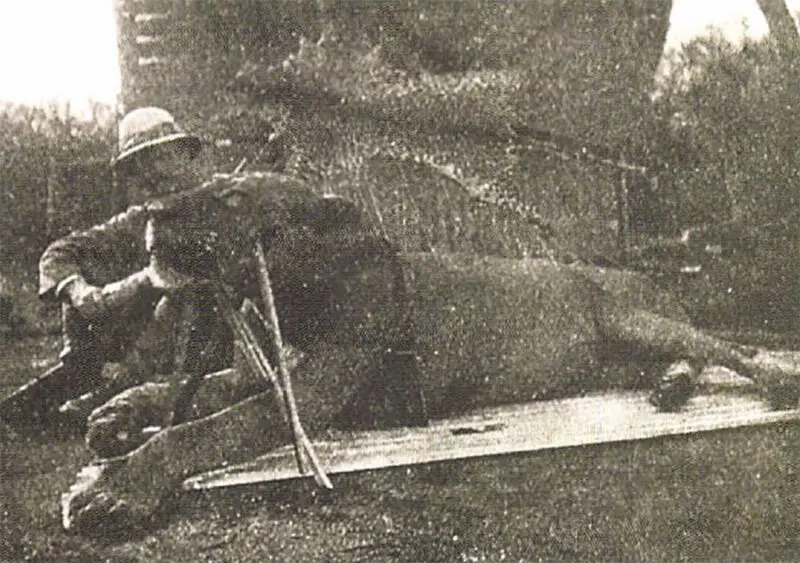

Patterson with one of the lions that terrorized the Uganda Railway.

But the other man only stood there. His eyes were fixed on this thing that wanted to kill him: his mouth was a little open, foolish looking. He was holding a London-made 450 express double rifle, and as the elephant opened its mouth and screamed, he could have raised it and put a bullet up through the mouth and into the brain — but he did not.

“For God’s sake, shoot!”

But the amateur hunter could only stand there. He was trembling.

The veteran raised his own gun. It was the wrong gun for the task — an old military Martini-Henry carbine in 577/450, its load behind the heavy ball hardly better than a shotgun’s. But it was all he had.

His face contorted with contempt for this man who stood transfixed beside him, he raised his gun and fired, then worked the breech to reload.

The elephant recoiled a step as that ponderous bullet struck, and it screamed and recovered and came on. A gun-bearer, trying to dodge the charging elephant almost fell under it. The veteran shot again, the whole world coming down to that dark, dusty mass of flesh. The Martini-Henry boomed like a kettledrum; the elephant bellowed and turned away from the bitter smoke and tile noise and passed them, so close tile man could feel the breeze of its rush.

As the beast went by, it reached for the gun-bearer with its trunk, to rip him and trample him. But it only knocked the cap off his head. It crashed into the acacias and disappeared, leaving behind it an incredible roar that hovered in the hot, thick air before dying in an absolute silence.

The man with the Martini-Henry felt his heart thud and turn over. His knees were weak and he could feel the sweat starting under his arms. He glanced at the amateur, still clutching his express rifle, still staring at the spot where the elephant had disappeared.

“Why don’t you go wait with your wife,” the veteran said. “I’ll take care of the elephant. Alone.”

He didn’t wait for an answer. With a signal to one of the gun-bearers, he walked into the acacias after the animal, and the black man in the ragged European clothes followed.

There would have been nothing for the man with the express rifle to say, anyway. It was all too complicated by then, most of all by his wife, and the affair he knew she was having with the veteran hunter, here in tile godforsaken bush.

The husband handed his rifle blindly to a gun-bearer. He took a step and staggered and sweat broke out all over him.

Thirty-six hours later he lay dead, his head burst apart by a bullet.

And his wife and the other man went on with the safari.

This real sequence of events happened in East Africa, in March, 1908. Twenty-six years later the dean of professional hunters, Philip Percival, told the story — minus the real names — to Ernest Hemingway, who turned it into one of the classic short stories about Africa, The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber. Twelve years after that it was made into a motion picture called The Macomber Affair, starling Gregory Peck as the veteran hunter, Robert Preston as the husband and a stunning Joan Bennett as the wife Hemingway called a bitch. Except for its tacked-on and silly ending, it was the best movie Hollywood ever made from a Hemingway story.

Yet, when the movie was made, the identities of the real-life figures were kept secret. Ironically, the man whom Peck portrayed was actually living in Los Angeles when the movie was released.

Who was the veteran hunter? And who was the woman who, in Hemingway’s version, put the bullet into the back of her husband’s head? And was the husband the “nice jerk” of Hemingway, or was he the angry coward so brilliantly played by Preston? Or was he the “English lord” of the gossip that still goes around.

Sometimes, fact is not only stranger than fiction, but a lot more interesting as well. In this case the veteran, the red-faced Wilson of Hemingway’s story, the man played by the handsome Peck, was and still is famous for another of East Africa’s greatest big-game feats. The book he wrote about it is still in print and is a hunting classic.

Pattersons photograph of James and Ethel Blyth on safari would later appear in his book, The Man-Eaters of Tsavo.

This man was John Henry Patterson. The book was The Man-Eaters of Tsavo, the tale of the man who saved the Uganda railway from man-eating lions in 1898.

So how did this hero, a best-selling author, become involved in a scandal that generated the ugliest of campfire gossip? And how did he lose his East African career, and his reputation, because of it?

A great deal of nonsense has been written about John Henry Patterson — some of it by Patterson himself, who was a master of personal disinformation — so that his legend has come totally unstuck from reality. In the legend, he is a well-to-do gentleman, an educated man (public school and Sandhurst, The British WestPoint), and above all, a “sportsman.”

In his legend he is always Lieutenant Colonel Patterson, and the rank is always assumed to have been earned by his steady climb from his commissioning after Sandhurst. The legend assumes he was a military engineer, thus explaining his working on the Uganda Railway long enough to kill the lions before dashing off to volunteer for the Boer War.

In fact, Patterson was none of these things. He was not wealthy; he was not a Sandhurst graduate; he was not a British Army lieutenant colonel (not until World War I, at any rate); and he was not what the British call a gentleman.

In fact, John Henry Patterson enlisted in the British Army as a private at Dublin in 1885. Until then he had been a groom in somebody’s stable. He later gave so many versions of his birth date and place that it is impossible to pin them down, but he was probably 16 or so in 1885, an emaciated Irish kid with a first-rate mind and incredible courage, but no future.

The army became his mother and father — and his school. In 1886 he shipped for India where he spent the next eight years with the Third Dragoon Guards. All the education he ever got was in the Army — the first and second class certificates of education, Lower Standard Hindustani, the sub-engineer’s certificate. (Sony — no Sandhurst.) He rose to the rank of sergeant and moved to the “unattached list,” meaning that he served as a civilian n the Indian department (railways) while remaining in the military. In 1897 he left: the Army and Signed on with the Uganda Railway as a junior assistant engineer, thus making his appointment with the lions and fame at Tsavo.

There was no question that he killed the lions, or that he did so heroically, if fairly stupidly. (He knew nothing about lion hunting and had virtually no help — he should have been killed). He left the railway in a fit of pique, forfeiting the cost of passage both out and back, and returned to London to find himself in 1899 with a wife, no job and no prospects. He asked for his old railway position back and was refused.

Then the Boer War crooked its finger at him.

Patterson in 1907, then a lieutenant in the Boer War.

Somehow — we shall never know how — Patterson got himself a commission in the gentlemanly Yeomanry. (Rather like an upper-class version of our National Guard, it became the Imperial Yeomanry when it served outside Britain. The initials I.Y. were said by regulars to stand for “I Yield,” although this was certainly not true in Patterson’s case.)

By then he must have talked like a gent and dressed like a gent; well, if it talks like one and walks like one … Anyway, in 18 months he rose from lieutenant to acting lieutenant colonel of Yeomanry (not of the British Army), had his own command and was awarded the D.S.O. for heroism. (You have to smile at the image of the former sergeant of the dragoons leading a regiment made up of gentleman riders.) After the war ended, he was an honorary lieutenant colonel, with the permanent rank of captain and later, major.

And then the legend began. From this point Patterson reinvented his past to match the man he had become. Ireland faded further and further away in a romantic mist (he once gave his birthplace as London); his parentage took on more gloss (his death certificate lists his father’s occupation as “general”); and through his new friends in the Yeomanry he rose to a new position. This included, in 1907, his appointment as the Senior Game Hanger (warden) of the East Africa Protectorate — more or less modern Kenya.

In 1908, after only a couple of months in his new position in Africa, Patterson organized a big safari to go into the unexplored country 300 miles north of Nairobi. His mission was to lay out a new eastern boundary for the Northern Game Reserve, which at that time filled most of modem Kenya’s northern region. The area was inhospitable, mostly semi-desert; the route to it was lined with tribes still hostile to the British; and just to the north lay Abyssinia, home to large bands of heavily armed and quite ruthless raiders.

So Patterson invited two London friends to go along. One of them was a woman.

James Audley Blyth was the younger son of Lord Blyth, one of the heirs to the Gilbey liquor fortune. Young Blyth had been an officer in Patterson’s peacetime Yeomanry outfit, a Boer War veteran and a passionate horse breeder.

Ethel Jane Bruner Blyth was a daughter of Sir John Tomlinson Brunner, a self-made millionaire and a staunch financial supporter of the Liberal Party, then in power. Ethel (Effie) Jane was in her late 20s, wealthy in her own right, willful, handsome if not beautiful.

The Blyths had one child, which they left in England. They no doubt seemed a happy enough aristocratic couple; however there was a worm in the rose, one that Patterson did not apparently know about: James was an alcoholic. Perhaps this East African safari was meant to dry him out (he had reportedly been hospitalized with the DTs not long before.) Perhaps it signaled an attempt to repair damage done to his marriage by his drinking.

Whatever the goal, the safari became a recipe for disaster.

They set out from Nairobi in February, 1908. Patterson led on a gorgeous white Arabian, Abdullah, followed by his old dog Lurcher. The Blyths were horse people and also rode. One of the affinities between Patterson and Effie Blyth was their love of horses — his, of course began when he was a groom. Another was Effie’s money, which she had and Patterson almost certainly desired. They traveled north, then west to avoid the hostile areas, hunting a little as they went. James wrote a letter home, describing the terror of backing a lion in the grass higher than his head, moving with the safety off the double rifle, not knowing where the animal was.

Effie Blyth was the star of the safari. She turned out to be a brilliant shot who had no trouble handling a 450 express. The Samburu warriors, who prize carefully done hair, were stunned by Effie’s long brown braids and eagerly touched her hair. Effie, wearing breeches like a man (most women in East Africa still hunted in skirts), rode and shot and dazzled.

And then James Audley Blyth got sick. First, he injured a foot; it healed over, abscessed, burst. He had to be carried on a litter. Effie and Patterson rode on ahead — together. James would get better for a day or two and totter around, even riding now and again, and then he would sweat and shake, and they would have to carry him again. He probably got malaria at some point; his alcohol-weakened immune system staggered under the twin blows of the abscess and disease.

The safari had by then turned east and north and reached the Ewaso Nyiro River. Patterson led them along the river to Neumman’s Camp (about where Samburu Lodge is now), where the legendary elephant hunter Alfred Neumann had his base until his suicide two years before. There, Effie got sick and the dog Lurcher died. Patterson, in the dumps, tended to both the Blyths — in their tent or in his own (who knows, perhaps he dreamed of a different arrangement).

Effie improved and they went on. Twice, they discussed the Blyths’ or at least James’, going back. But now they were so far away from any European contact that it was impossible to send this sick Englishman, who spoke no African languages, off by himself. Patterson may have, in fact, tried to make Blyth go back, leaving himself with Effie; surviving accounts are ambiguous on the point. The upshot was that all three of them went on, with an inevitable result.

Their rendezvous with tragedy was a place called Laisamis. It still has that name, a broad, gently rising flat surrounded by some shops and one-story buildings, in a rocky desert with a sand lugga trickling by and an Italian mission not far away. In 1908, there were no buildings and no missionaries, only some pools of water in the lugga and the great nowhere all around.

Two days before they reached Laisamis they met the elephant. Patterson later said it was a rogue, a male made dangerous by isolation from the herd. James was riding that day, feeling a little better.

The three got down from their horses. Patterson told Effie to shoot, it was her elephant – one of the few species she hadn’t shot so far. She hit the bull twice with the 450, and it thundered into the bush. The two men went after it on foot while Effie stayed with the horses and the safari — a curious bit of sexism, as she was would have been a far better companion in a tough situation than the sick Blyth. But by this time, a rivalry based on class and money and military rank may have developed between the two men, and Blyth may well have known he was now competing for his own wife. So he took the express rifle and set out. And then they met the elephant and Patterson hit it twice with his Martini-Henry and then sent Blyth back to camp and went after the elephant alone.

The next hour was perilous confusion as Patterson tracked the elephant, while the elephant tracked the safari. The natives told Effie that Patterson had been killed by the bull; Patterson was told Effie had been killed and when he at last caught up with the beast, it was anticlimactically dead from its wounds.

The only real victim of the elephant was Patterson’s prized Arabian. In one of its charges, the bull had put a tusk through the horse’s vitals.

That night the two men had a shouting argument, which Effie mediated. The ostensible subject was, apparently, the elephant’s tusks: Patterson evidently wanted one as repayment for Abdullah. The real subject, not spoken, was nearer the hearts and loins.

But they patched it over and went on to Laisamis where Blyth went out hunting and collapsed. Delirious and unable to stand, he was put to bed in his tent.

Effie spent the night — her first —in Patterson’s tent.

In the morning, Patterson exchanged a few civil words with James Blyth and then went to the center of the camp to oversee the loading. (There was no dispute as to where he was.) Effie Blyth got up, dressed and crossed from Patterson’s tent to her husband’s.

And then the conflicting testimony and gossip and speculation take over. Two things happened for sure, but people differ about which happened first: Effie screamed, and a gun went off. She may have actually been in the tent, or she may been in the doorway. And she may have exchanged a few words with her husband.

Then Effie ran from the tent, and Patterson and his headman and the porters rushed to it, and they found James Audley Blyth with a gaping wound in his head, and a 450 revolver.

Later in Nairobi, the porters all testified that the wound was on the back of Blyth’s head, and the gun was in his hand: Patterson, however, first testified that the wound was in the temple, and both he and headman Mwenyakai bin Diwani — who seems to have been the first inside the tent — testified that Patterson picked up the gun and handed it to the headman.

At which point somebody must have put it back in Blyth’s hand, because that was where the porters saw it, with the muzzle in the dying man’s mouth — unless they somehow saw it the instant before Patterson handed it to the headman. Or perhaps Patterson or Mwenyakai put it back into Blyth’s hand so the porters could see the way it had been.

At any rate, it seems impossible that a dozen or so porters all saw precisely the same thing and reported it in precisely the same words after only a second or two of looking. Far more likely — hence their use of the same words later — was their being made to see, with somebody (Patterson?) standing there and saying, “See? The point (the word they all used) is in his mouth and his thumb is on the trigger.”

At Patterson’s direction, they burned all of James Audley Blyth’s clothes and papers and buried him in an intentionally shallow grave.

And Patterson took the safari on north, sharing his tent with Effie for the six weeks it took them to get up to Marsabit and back to Nairobi.

The ensuing scandal stunned Patterson and appalled Effie Blyth. Both left Narobi after the most cursory of testimony, but they found no haven in London. Communication was good between the Protectorate and England, because many colonists had friends and relatives back home. By the next summer Patterson was being accused in private of adultery and murder, with an official accusation of theft: of government funds thrown in by the Nairobi administration (with good justification, it appears).

The inquest (extra-legal, conducted by a Nairobi Magistrate for lack of anybody else) gathered such testimony as it could, but there was no exhumation of the body, no visit to Laisamis, no forensic examination. Ironically, the Northern Game Reserve was outside normal jurisdictions, so there wasn’t a legal mechanism for doing police work anyway.

An official verdict of suicide was issued; nonetheless, by the following year as powerful a personas Winston Churchill was alleged to have said that he knew Patterson was guilty of theft, adultery and murder. (Churchill, under-secretary of the Colonial Office when Patterson was appointed, had made an East African trip just before the event and had friends there.)

Despite public exoneration in the House of Lords in 1909, Patterson had to resign his position, and he never went back to East Africa. Fate touched him again, however, when he took charge of the Jewish Transport Corps at Gallipoli. At this command he led the Jewish Legion in Palestine in 1918-19, which resulted in his enshrinement as a hero in modern Israel where his medals and uniforms are now in a museum.

Effie’s wealthy father had engineered a complete cover-up of her part in both the affair and death, a whitewash so complete that Lord Crewe, then the colonial secretary, wrote to an acquaintance that he had endangered his immortal soul by lying. (It was Crewe who had to assure the house that no crimes had been committed.) Papa Brunner cut a deal that had Patterson resigning and shutting up about Effie’s role in exchange for the official exoneration.

Despite what the legend and the gossip later said, Patterson and Effie did not marry. Patterson was an ambitious man, certainly not above dreaming of being Effie’s second husband, a millionaire’s son-in-law. But it never happened. They did not run away together, as some people have reported since. They probably did not even see each other after 1909.

But in East Africa, the story survived, so vigorously that in 1934, professional hunter Philip Percival sat one night by the fire with an American client and told the mustachioed writer the story. And it clicked with Ernest Hemingway’s ideas of courage and fidelity, and the tricky interplay between men and women.

Shadows in the Grass by John Seerey-Lester

Now, Phil Percival was the brother of Blayney, the man who lost his job as head of the game department to Patterson. He had good reason to despise Patterson. So it would not be surprising if his version made Patterson the villain. Yet that is not the way Hemingway wrote it: quite the contrary. His Wilson, the professional hunter, is the terse arbiter of courage and male morality. Based on Bror Blixen and Phil Percival himself, he is a model Hemingway man. And in making the husband the victim o fa gun fired by the wife, Hemingway may have picked up something suggested by Percival — that it was Effie, not Patterson, who shot James Audley Blyth.

To do so, however, Percival would have to be privy either to the official inquest records (not impossible, as the Nairobi government was as porous as a burlap sack) or to gossip from the safari porters themselves. At any rate, Phil Percival passed on the story in aversion that allowed Hemingway to make Phil’s brother’s old enemy the moral center.

As to what really happened in those few seconds in the tent at Laisamis, only three people could have known: Effie Blyth, Patterson and the headman Mwenyakai — and they never told. Did Ethel Jane Brunner Blyth step into her husband’s tent, raise the revolver and shoot the sleeping man in the back of the head? Or did she walk in to find him feverish and raving, a gun in his hand, accusations spilling from a mouth that he himself stopped with the pistol barrel and the shot?

We shall never know. One tantalizing fact persists: A year after the public whitewash, Patterson still had a sword to dangle over Papa Brunner’s head, one that caused Lord Crewe to refer to him as “dangerous” and ultimately to warn him off. This threat could have been merely the facts of his and Effie’s affair. Or it could have been a fact that only Patterson and Mwenyakai knew: the location of the pistol when they entered the tent.

The Irish groom, the honorary lieutenant-colonel, the hero of Tsavo, died in Los Angeles in 1947, taking his threats and secrets with him.

In 1898 John H. Patterson arrived in East Africa with a mission to build a railway bridge over the Tsavo River. Over the course of several weeks Patterson and his mostly Indian workforce were systematically hunted by two man-eating lions. In all, 100 workers were killed, and the entire bridge-building project was delayed. Buy Now

In 1898 John H. Patterson arrived in East Africa with a mission to build a railway bridge over the Tsavo River. Over the course of several weeks Patterson and his mostly Indian workforce were systematically hunted by two man-eating lions. In all, 100 workers were killed, and the entire bridge-building project was delayed. Buy Now