The blue sea was red now . . . and black. Black from the ink of the octopus, red from the blood of the swordfish.

When we slipped into the harbor that night, we dropped anchor and secured. I’d been there before. It wasn’t anything to write home about. It was Puerto Bayovar, about 50 nautical miles south of Talara, one of those vague Peruvian stopovers that exist mostly on paper. It’s a name on a map, not a town.

It’s a place where Indian fishermen unload their catches and moor their pupit-rigged harpooners after a week’s cruise on the Humboldt.

But it’s lousy with pes espada or swordfish. That’s why I had come. An 8,000-mile round trip from New York for a series of newspaper stories to give tabloid readers a lot for their nickel. Actually, though, I hadn’t expected to fish Bayovar. But the fish were not off their usual haunt, Talara.

So after exactly three weeks of horsing around the northern area with nothing to show for my troubles, I began feeling a little desolate. I had to do something fast—the first plane back to New York and take an awful ribbing or try Bayovar. I decided I wanted swordfish at any price, even if it meant a week of hot, stinking, moribund Bayovar where the buzzards are always so glutted with carrion they can’t fly. They just sit there in the thick dirt.

That’s when I hooked up with Jorge.

I shelled out my last 3,000 soles for gas and provisions and hired the kid and his rig for a week. Jorge knew the pes espada. But beyond this, he knew little or nothing about rod and reel. He was brought up with a harpoon in his hand and an insatiable love of the sea.

He smiled frequently. His eyes were dark and warm. He was about 20. Aboard the boat, his movements were quick and confident. On the trip down the coast, we went through the mumbo jumbo of boating an imaginary swordfish. Jorge caught on fast.

We’d rigged a makeshift fighting chair in the cockpit and gone through the business of acting out a battle from strike to finish. He had it down pat, all but the business of lashing a tail-strap onto the beaten fish. For some reason or another, he didn’t get the idea that I wanted him in the boat. His impression of tail-strapping was to jump overboard and work from the water, and I dropped the matter after a while.

“Desayuno senor!” he called out the next morning. Breakfast.

I crawled out of the sack. It was an hour before daybreak. Jorge had the bacon frying and the aroma of strong Peruvian coffee wafted out from the galley.

I climbed into a pair of dungarees, tossed some water over my beard and joined him. In 15 minutes, we had finished, and the boat, an ancient 32-footer housing a Ford conversion, was made ready for the Humboldt. We checked out of Bayovar just as the sun came over the volcanic harbor racks to our stem.

The harbor was deserted. Deep within it, we could make out the huge barge that served as a collective storeroom for the swordfishing fleet. The very fact that the harbor was void of any activity was good, Jorge declared somberly. Harpooners don’t go in for sightseeing. If there aren’t any prospects, they remain in port, making with the siestas.

We chugged out at a leisurely nine-knot clip into a morning that was full of promise. The Humboldt Current was blue and slick, the kind of a sea where good eyes can pick up a dorsal fin far away.

I took the wheel while Jorge went below for the fishing tackle, harness and hooks. These he promptly rigged, whistling happily as he worked and, every once in a while, stopping, standing up and looking over the bow. When he finished rigging, he stowed the tackle on deck off to a side.

“Listo!” he said emphatically, dusting his hands.

A school of bonito curled ahead in the southeast, pocketing something smaller. Bait. Jorge dashed below and returned in an instant with a light rig. Then he dropped a Jap feather into die wash and I gunned tire boat ahead.

Twenty minutes later, we had a fishbox full of fresh bonitos. We were set.

Jorge took the wheel and I went below to get a big skinning knife from my duffle, and then broke out the gun case with the .348, rubbed it down once and loaded it. If Bayovar was the same as last time, and there wasn’t any reason to think otherwise, the bottom was carpeted with giant squid and who knows how many man-eating mako sharks.

Back in the States, people scoff when you talk about man-eating makos. A mako is a gamefish. Well, maybe it is. But down here, nobody scoffs at anything. A mako will eat if hungry, very definitely. So will a giant squid, or octopus, if you prefer. I guess the native fishermen of Peru fear the octopus infinitely more than they do a shark. They figure a man with a knife has a chance with a shark, but they don’t do any figuring when it comes to the huge, grotesque, parrot-mouthed strangler with eight arms that breeds in profusion at the edge of the Humboldt Current.

I took the knife to the fishbox and began cutting bait. In a half-hour, I had four rigged, fresh and clear-eyed for the most finicky of swordfish. Then, I took tire wheel again and Jorge climbed into the mast. We sailed southeast-by-east for an hour, saw nothing but a few mantas bouncing out of the water, then altered our course to the northwest.

The morning was bright and the sea slick. You couldn’t want it any better.

I guess we both spotted the sickle fin at the same moment.

Eight thousand miles, and there it was and from where we sat, it looked like the Queen Elizabeth.

Jorge climbed down from the mast and took over. We slowed the boat long enough for me to clip on the leader, then slip the harness around my shoulders. I had no fears. Jorge knew exactly what to do. He knew not to come too close to the swordfish—that it would sound for bottom if frightened.

“Listo?” he asked. Ready?

“Listo!”

I felt a surge of excitement. I loosened the drag a turn, then let the heavy line slip from the reel into the wake. The fish was off our beam now, cruising easily, as if he’d actually expected us. The bait curled around in an arc in front of his snout.

He wouldn’t take it.

We made a complete circle and Jorge slowed the motor this time as the bait almost nudged the fish. The bait settled beneath the surface. I took a deep breath, held it, let the line pour from the reel, waited. The dorsal disappeared. The fish sounded.

A hundred yards of line were whooshing off the reel and we were traveling straight away from the swordfish. Then I felt the tap. That’s the way they hit. The bill slashes out at the passing bait, ostensibly a live fish, and stuns it. Then the fish picks up the bait in his mouth and goes. And when he goes, there is nothing like it in God’s salt water.

Slam!

He had it. I yelped for Jorge to gun it ahead. The fish was on. He’d picked up and now he was going—going like a torpedo—a wild thing with a slab of sharp steel biting into its jaws. Three hundred yards of 39-thread poured away into the swirling trough behind us. Four hundred. Then Jorge held the boat steady and began giving me back a little line.

The first run was over, and my fish was settling now for the dogged part of the fight. But before this, he came out for a look. Showering the bluewater a dozen feet in the air, the fish erupted into his ballet, revealing his nine feet of black, slick, glistening body. Then he sounded. Then it happened.

I had something around 700 pounds. Jorge and I both knew it. Both of us worked as if it were the biggest, last swordfish in the Humboldt. But now, my fish was down, 300 yards down somewhere and instead of the steady, powerful strain that characterizes such runs normally, I felt a series of sharp, jolting tugs and the line abruptly became twice as heavy.

For a moment, I thought my fish must have died right there. The weight was that great. Then the line began seesawing all over the place and Jorge had an awful time keeping the boat in the correct position. Suddenly the line was slack. Frantically, I cranked the handle of the big rig, but the line held slack. I had almost recovered 100 yards when the line zoomed out and flattened, as if the fish were rising.

I’d never seen anything like it before. He came out in a cascade of white water that for a second obscured the thing on his back.

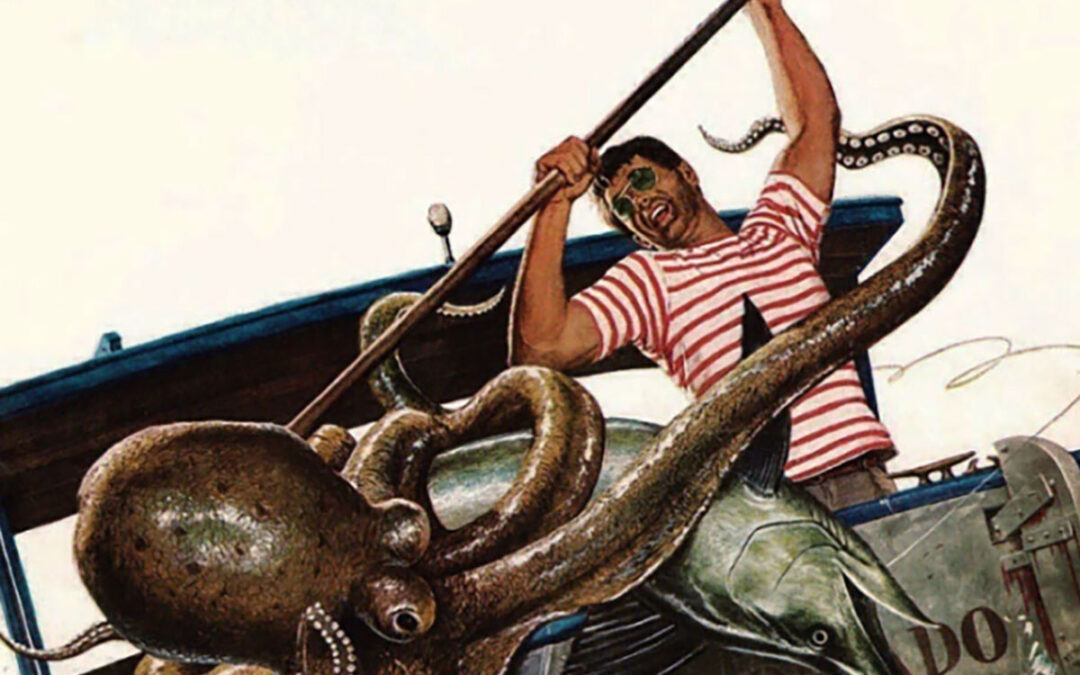

I was taking line and trying to tell myself such things just don’t happen, and the kid was yelping wildly. Where the sea was blue a moment before, it was now red. And black—black from the ink of the octopus, red from the blood of my swordfish.

I’d heard of fantastic dimensions for octopuses before, but I never thought I’d see a 300-pounder. It was a thrashing mass of flesh and it was tightening a stranglehold on my swordfish. In return, the swordfish did the only thing possible. It used its bill. Slashing, rolling, bounding high and then dropping flat, the swordfish tried desperately to bludgeon the octopus.

All sorts of thoughts ran idiotically through my head. Put down the reel and handline the fish. Okay, so the fish is disqualified, but nobody would believe my story anyway.

Then I thought of a solution. I told Jorge to back the boat down to a point where I could grab the leader wire. After that, I’d slack off on the drag, put the rod in the holder, grab the wire and hold until the kid could hand me the .348.

And that’s what we did. Exactly that. I had a ten-second opportunity. I grabbed the gun, aimed at the bulbous black head and fired. I jammed a second shot into the chamber, fired again. I heard the shots slam home. The thrashing moved from one quarter directly astern and the death struggle no longer was visible. The fish, and the octopus, if still alive, had decided to fight it out without interference below.

A moment later, I felt tension on the line again, felt it flatten again and up came my swordfish. You couldn’t see the black of his hide. He was a mass of crisscross gashes and welts. My fish was beaten. He made a few feeble attempts at rushing off some line, but when I put a little strain on the rod, he knew he was finished.

“Ahorita!” I roared. Now!

The kid backed the boat down and I felt the leader wire come home to the rod tip. I jumped up and shoved the tackle in the holder and slacked off, grabbing the leader with my free hand. The kid was back with me in a second.

I took the wire end over end until the four-foot bill, no longer a mighty weapon of destruction, was almost within grasp. The kid pulled out the flying gaff, bent over and shoved it in hard. Right behind the head.

“La lina!” I shouted. The line!

Jorge understood. He found a tail-strap, leaned far over the side, but the transom and the fish were too far apart. I hauled until the bill pricked my hands.

“Ahorita, chico!” Now, kid! But again, he just couldn’t make it. He took a quick look me, grinned and dived over. I couldn’t stop him. As soon as his head appeared, I shouted at him to get the hell back in the boat, but he wouldn’t answer. He tucked an arm around the fish’s tapering body and got a piece of the rump with the line.

I never saw Jorge after that.

A huge spray of white water showered over the stern, enveloping the kid. A hideous, bulbous head appeared in the center of the water-boil. I saw the kid’s head disappear under the black mass and the writhing, frantic jerking of his fingers to break the stranglehold. I saw ugly tentacles come up from under the swordfish. And then the scream. Just one scream. I grabbed the skinning knife and jumped overboard, slashing away at the thing that was squeezing Jorge.

The slime clouded the water while the tentacles closed around me. I hacked away with my knife, feeling the cold tentacles loosening. I felt the head and stabbed again. The octopus wedged me up against the dead swordfish, shoved his tentacles into my face and then backed off.

That’s the way it happened. The octopus dropped down. He had his trophy. Jorge. I had mine. A swordfish.

I pulled myself up and flopped into the cockpit, groaning, sobbing, sick and miserable. The kid was gone. He was really gone. I couldn’t believe it. It was fantastic fiction, something out of Jules Verne, but it had really happened, and I blamed myself now.

Somehow, I crawled into the cabin and found the water jug. I poured it over me and then closed my eyes. I lay there making believe I had never left civilization and that the boat was really tied up at the oil dock at Talara. I stayed there an hour, possibly, and then I got up.

I walked to the stem, looked over at my swordfish. It was floating belly up, the strap securely tied around the thick girth of its tail.

When I pulled into Talara, I went straight to the customs people. They, in return, called the police.

My explanation was accepted. I asked if the kid had any relatives. None, they asserted.

I left the boat with the port captain and went to the only hotel in town. I gave the bellboy a cable to send for me.

“Swordfish nailed. Coming home.”

Then I went to sleep. I slept for a couple of days. I wrote a few fishing pieces while I was there. But I never wrote a word about Jorge. You know how fish writers are, they’d say, when there’s nothing to write about, they beat out the weirdest copy.

Maybe they’ve got a point there.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now