Ford Riley’s goal is not just to paint what he sees while hunting and fishing — he wants to take you there, mind and soul.

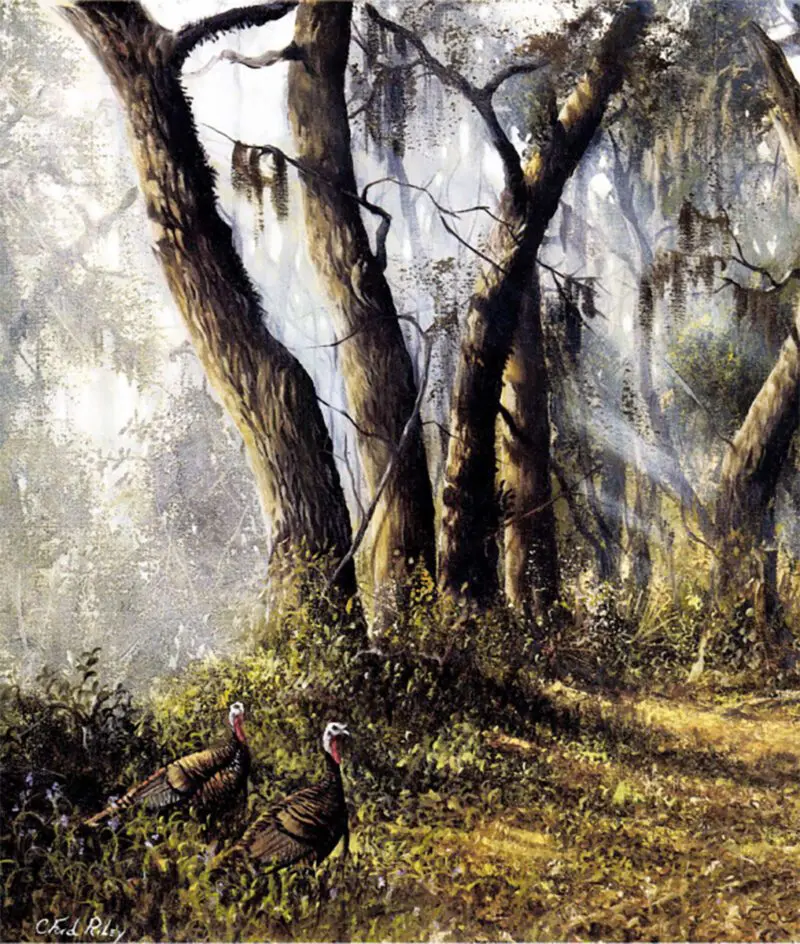

First Light relives a moment that C. Ford Riley experienced on many of the 44 mornings he spent hunting wild turkeys last spring.

Almost all of Riley’s paintings are inspired from his daily outings in the woods and on the water near his home along the St. John’s River just south of Jacksonville, Florida. Some of these canvases depict wildlife, but most are exquisitely detailed landscapes without any animals or human figures.

“The response I like to hear from people who see my work is, ‘I’ve seen that place; I’ve been there before.’ That’s what I strive for,” explains Riley.

“If I incorporate a flyfisherman into a painting, then the scene might mean something to that person with a flyrod, but it would have less meaning to someone who’s just out there taking in the elements. I’m even hesitant to put birds into some of my landscapes, because they would change the tone and feeling. I don’t want to close off the viewer by putting in an object; I want him to search deep within and find his own story behind the painting.”

American Woodcock.

Riley’s expansive studio overlooking the St. John’s reveals an artist as full of life as his vibrant paintings. In one corner is a bass rod, in another a guitar. On a shelf is a cluster of turkey beards — turkey hunting is one of Riley’s passions.

All of these things reflect the life of Riley — artist, angler, hunter, amateur musician, father and husband. The 45-year-old admits to being compulsive. He toys with the idea of putting together a blues band, and when the waves are right at nearby Ponte Verde Beach, he’ll slip away to surf for a couple of hours.

“He’s an independent guy,” says Scott Riley, who sells his brother’s art through Stellers Gallery in Jacksonville. “He probably could have gone with one of the big art publishers in the country, but they would have said, ‘Ford, we need you in New York this week,’ and he’d have said, ‘No way — I’ve got to turkey hunt.'”

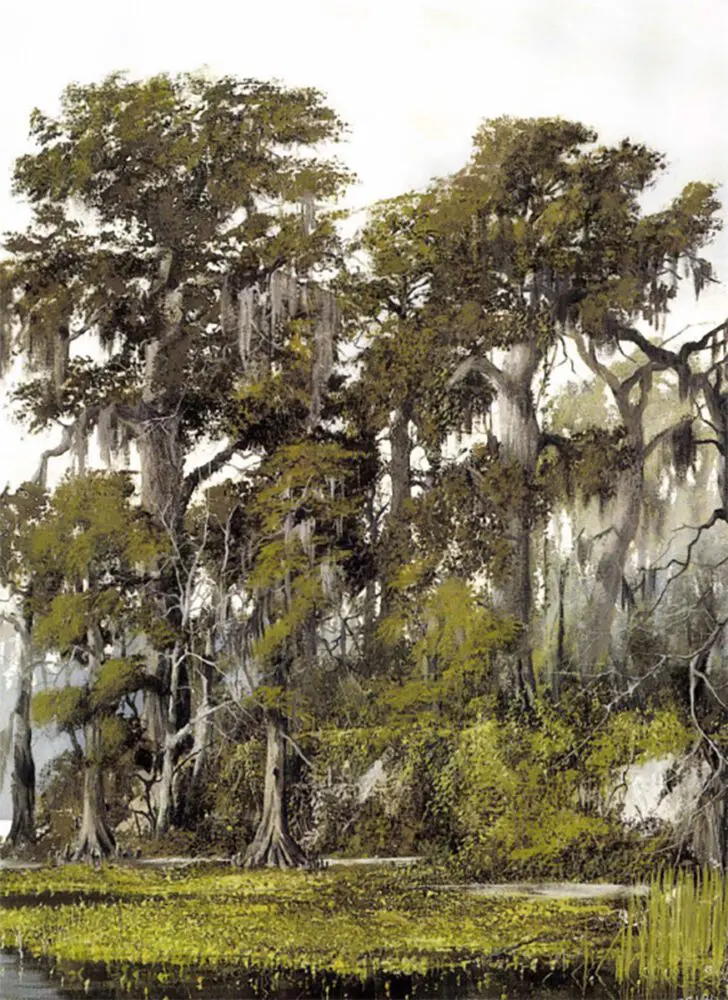

“This scene is right in front of our home along the St. John’s,” says the artist. “Most of the large cypress have been logged off, but these smaller ones remain, along with the two great oaks that stand like sentinels overlooking the river.

It’s quite likely that no other American sportsman spends as much time hunting and fishing as does Riley. During Florida’s recent 45-day wild turkey season, he was in the woods every morning except one. “I shot my limit pretty early in the season, all birds with ten-inch or better beards. After that I called in several gobblers for friends and a bunch more just to study them — heck, just to play with them,” he adds. “Once turkey season was over, I was out every morning catching huge redfish right in front of our house, and now [mid-May] the cobia are biting.”

“Not long ago my wife asked me, ‘Isn’t there a time-period that’s not a hunting or fishing season?’ I told her ‘not really — it’s a continuous cycle.’ Before you know it, I’ll be scouting deer prior to our September bowhunting season and then comes duck hunting … now there’s something I really love.”

Over the past 365 days, Riley hunted or fished all but three mornings: on Mother’s Day, Easter and Christmas. He typically rises about 1 or 2am, sips coffee with the other graveyard shifters at the 24-hour convenience store down the street, then returns to his studio for several hours behind the canvas.

“One of the reasons I get up so early is so I can get in a few hours of painting and hit that treestand or be on the water at first light,” Riley says. “I see that as part of my work. I believe that you can’t accurately portray things in the outdoors unless you live them.”

Barred Owl.

By mid-morning Riley is back in the studio next to his home, either painting or working on business matters. He breaks in the afternoon, maybe to watch his seven-year-old son Christopher play T-ball or work in the yard with wife Liz. He’s usually in bed by 8pm.

“I don’t think I’ve missed a sunrise or sunset for the last 20 years,” he insists.

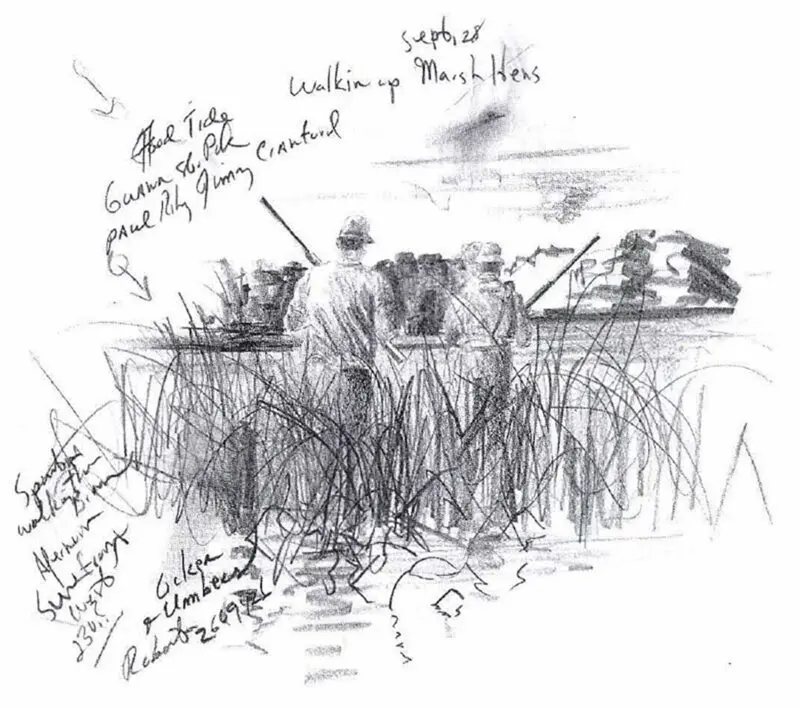

Riley always carries a sketchpad into the field, in addition to a bow or gun during hunting season. He never leaves the woods without at least an idea for a painting. “Observing is the fun part. I just take it all in — how the sun casts shadows on things, the sky patterns.

Riley on a cobia trip, one of the many “seasons” he pursues year-round.

“I think most people are surprised that I like to hunt. But it’s not what I’m after that’s important, and I think it’s that way with ninety percent of the people who hunt. What’s important is to get out, put everything aside and get back to that primeval drive.”

Riley enjoys drawing and painting pleine aire, then transferring his field sketches into oils on canvas back at the studio. Works in progress occupy every cranny of his pine-ceilinged studio. “I have no idea how many paintings I’ve done, but I’m a very fast worker. There must be 30 paintings started in here right now, and another 30 on the shelves and 30 more in my head.”

Riley’s affinity for the outdoors showed itself early in his Jacksonville childhood. To this day, he remembers holding a cedar waxwing in his hands, fascinated by the bird’s vivid coloration. Following graduation from high school, he attended Shorter College in Rome, Georgia, then joined the family vacuum cleaner business.

“This oak and hickory grove is where I do a lot of my turkey hunting, ” says Riley. “I wanted to convey a feeling of stillness, but the road leads you out of the painting, to a different place and maybe a different feeling.

But it wasn’t a good fit. Riley, who had been drawing since he was a youngster, wanted to paint. Maureen Riley, an artist herself, gave her son the push he needed. “My mom encouraged me to do what I wanted to do, which is the best advice I ever had,” says the artist.

With no formal art training, Riley began painting birds and landscapes in watercolors at age 21. He sold his first painting for $250. The Riley brothers teamed up eleven years ago — Ford in the studio, Scott handling the business end in the gallery.

“Before then, he found himself more and more involved with business,” Scott says. “I told him, ‘Ford, all I want you to do is hunt, fish, surf and paint.'”

“Undoubtedly, his work has gone more and more national. It started about 1990 when he became the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition featured artist. Since then, everything’s gone kind of crazy.”

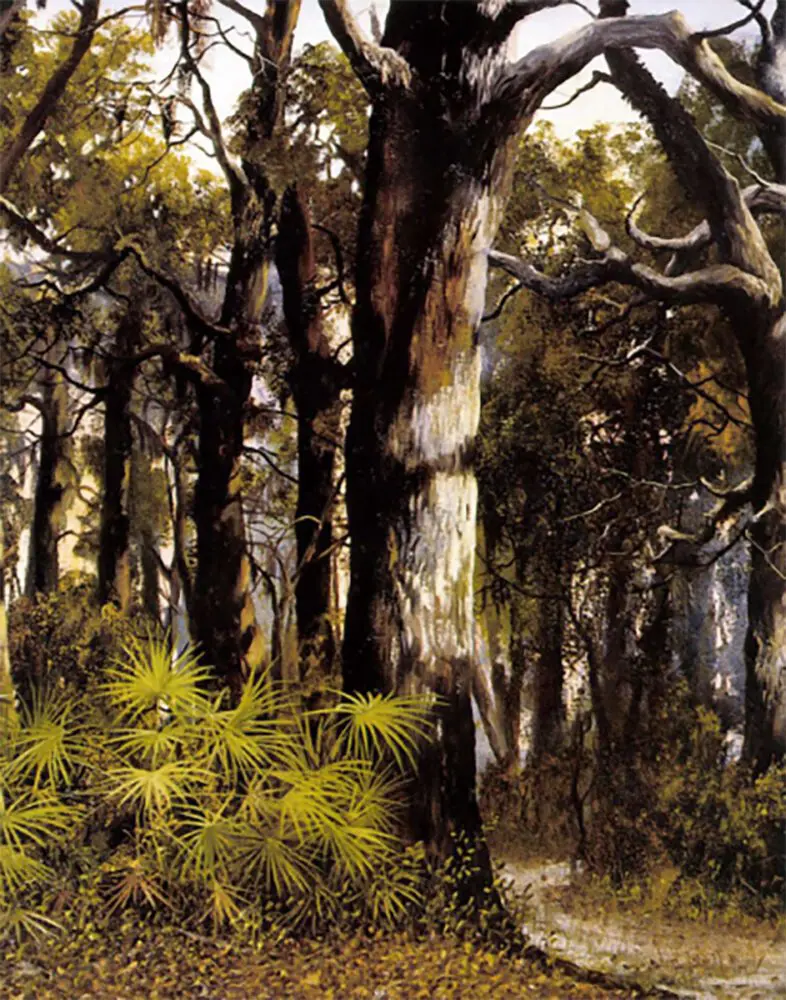

“God’s own creation,” is how Riley describes Fort George Island on the Florida coast. “It’s a beautiful place, especially early in the morning with a slight mist in the air. “

Today, working mostly in oils, Riley gets anywhere from $5,000 to $45,000 a painting, with the typical piece going for $15,000. Scott, who keeps track of such things, said his brother averages about forty originals a year, which end up in private and corporate collections around the country, in addition to the fund-raising campaigns of Ducks Unlimited, the National Wild Turkey Federation and other conservation organizations.

“What’s been phenomenal is that corporations have started to buy up my work,” Riley points out. “Schools and tours can now call these institutions and view many of my paintings and that’s great. It’s really important to an artist. If they were all in private homes, you’d never see them.”

Whoever does see his art is immediately taken by the stirring realism — of the trees and grasses, the water and clouds and sky. Always, it seems, there is a dramatic play of light: shafts of amber filtering through the canopies of ancient oaks or cypress. It is the time of the hunter and fisherman, when the animals are moving and the fish biting.

Sketches like this one form the foundation of his paintings.

“I’m more of a mood and light painter than anything else,” says Riley. “The light is especially important; if it’s not there I create it factually, which I can do because I spend so much of my time outdoors.

“I love storms, and I enjoy painting the remnants of a front, because the more clouds you have, the more color you’ll see in the sky. I also like changes in the seasons. I’d much rather paint the transition between spring and summer, because there are so many different shapes and colors,” he says. “When it’s full summer, everything tends to be the same color, and that doesn’t interest me.

Canvasbacks wing over a quiet tidal marsh at sunrise.

“You have to stand back and take my paintings in as a whole — you can’t visualize on just one aspect. That’s the way you should view any work of art.”

Adds brother Scott: “He paints the old roads, the marshes and the skies better than anybody. He paints things people truly understand.”

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1997 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now