I dropped to my knees and anchored my homemade bamboo shooting sticks firmly into the ground and eased my rifle into their forks. My mind was quiet and my hands were relaxed, and I heard Frank whisper “. . . second one from the left” from somewhere unseen as the great buck materialized in my scope.

The crosshairs found him whole and quartering away, then crept forward across his flank before settling centered into the back of his chest. I tried to visualize the forward path the heavy partition bullet would take to the point of his opposite, far-left shoulder, then eased my rifle off-safety, evenly emptied my lungs, and coldly crushed the trigger.

His chest seemed to implode as the bullet struck. But his first bounding leaps betrayed no evidence of the piercing devastation within, and as he bolted back up the ridge into the thick brush, I racked a second round into the chamber. The rest of his race went flying down the mountain in sudden realization of the silent treachery that had just overtaken them and their stricken leader, the whites of whose eyes must rarely before have ever been so exposed except in times of great stress or sudden rage, but which now must surely have flashed wide and pallid.

“You hit him hard!” Frank exclaimed, and he grinned and slapped me sideways as we rose from the ground. With the light fading, we left the camera and shooting sticks where they fell and tore across the face of the mountain to where the buck had disappeared.

“I think he went in here,” Frank said as we reached the edge of the oaks, a tangled maze of narrow twisted paths, up any of which the buck might have fled. But there was no track, no trail, no spatter of blood to betray him, and unsure of our position, we split up, me going higher and Frank moving off to the north.

The shot had felt good. But now as I made my way deeper into the thick oak brush I slowly began to question the trail, to question the bullet placement, to question myself as I tried to visualize the crosshairs on his chest.

There should be blood, but there is no blood; there should be time, but time is fading with the light. Could it be I missed him? Could it be we are looking in the wrong place? Where is Frank; where is the deer; where am I . . . and I picked up movement below me and to the right.

And there he was: not the deer, not Frank, but Crockett – good old Crockett! – for by now Frank had circled back down to the truck for him. The old dog flew up the slope past me, lightly brushing my leg as he passed as if to say “Follow me!” and disappeared into the tangled oaks. And then there was silence.

For nearly a minute a vague stillness descended and there was no sound—no evening wind, no rustle of leaves nor tick of stone on stone. Nothing, except my own steady breathing and quickened heartbeat, and I feared we had lost him.

Then Crockett reappeared, a dim charcoal-grey shadow bearing full tilt past me back down the mountain, his nose held low into the shifting evening breezes rising from the valley below.

“Crockett!” Frank called from somewhere out in the dusk, then tried to whistle him in.

“He just passed me heading your way,” I responded, my eyes scouring the stony ground and probing side to side into the dark inner reaches of the thick, dimming brush, longing, hoping, praying for anything that might betray the least sign of the old buck. My mind flashed back to that big bull elk all those years ago and my deflected arrow, and I began to hope that somehow I might have missed this deer cleanly. But in my heart I knew he was hit, and all we could do was press on.

And then I saw him—my old friend Crockett laying there 60 yards below me, down on one side and appearing totally exhausted from his frantic dash, a panting grey wraith barely visible in the edge of the dusky oaks, head cocked, eyes pleading, his face raised to me with a beckoning, imploring countenance. “Crockett!” I begged. “C’mon bud’ – we need you up here!

But he did not stir.

Then Frank appeared 40 yards below and also spotted him.

“Crockett?” he called, then took a couple of steps toward him before halting abruptly. He lowered his shoulders, lowered his head, lowered his gaze, then slowly turned and looked up the ridge to me with a big cowboy grin in his voice and declared, “Hey ol’ buddy, here’s your deer!”

We had clearly been on the wrong trail, for the buck had died only seconds after being hit, his last impulse to burrow deep into the darkened thicket where, without Crockett, we would likely have not found him until daybreak.

He was stone cold dead, a big beautiful blessing of a deer, buried in the edge of thick oak brush with Crockett nestled tight up against him and wearing a smug, self-congratulatory smirk on his big furry face that seemed to say, “What took you boys so long?” And as Frank and I eased the deer out into the open, the old dog romped around us in victory, and for a moment we were all pups again . . .

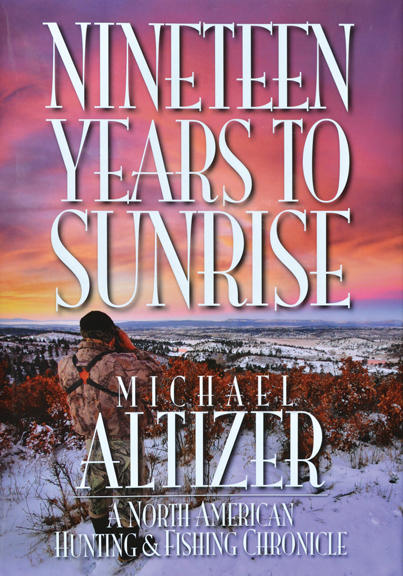

Excerpt from “The Spirits of Cerro Venado Macho” from Michael Altizer’s “Nineteen Years to Sunrise” Buy it Here!