Largest of all reptiles, the crocodile is arguably the deadliest creature ever to walk or swim the face of the earth.

Water beckons to most of the world. The inland bodies: lakes, streams, rivers and ponds, shimmer blue and tempting, time of passage, a respite from heat and drought, a shining solace, life-giving. In most parts of the world, that is.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the water can be as inviting but far less kind — malevolent, in fact. In much of Africa the shining waters can explode suddenly and seize you. They can draw you down in a horrible convolution of maligned head and teeth — a great serrated trap sprung, unsprung and springing again, in fractions of seconds perhaps, tighter and higher up your torso as light-filled water caves in above. There is one great gasp of shock and hopeless reflex to struggle as all goes deeper and darker. The awful twisting and tearing, the muted outrage of your last tortured scream.

Commonly reaching 16 feet in length, Africa’s Nile crocodile has, for centuries, been the world’s most prolific man-eater. In the 1940s and 50s, when East Africa was still under British rule, Nile crocodiles killed over a thousand people each year. Even today, in the coastal areas of Australia and the Indian subcontinent, saltwater crocodiles kill at least that number annually.

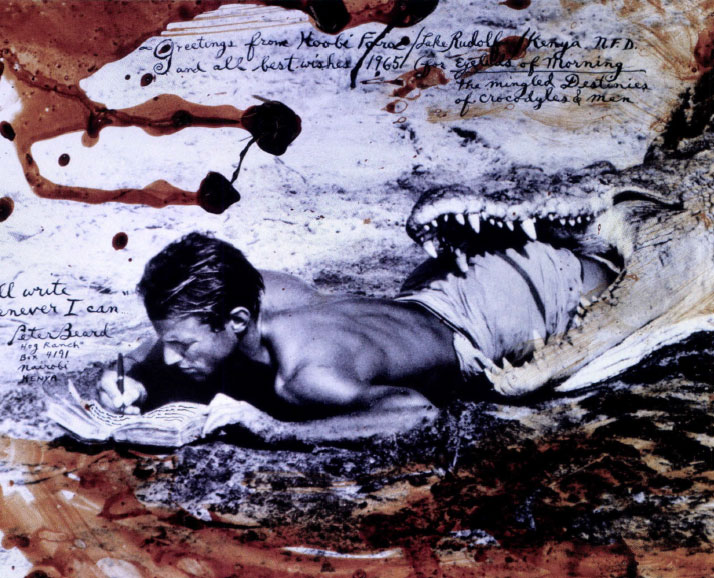

Peter Beard killed this 15 1/2-foot, half-ton monster while

researching crocodiles at Lake Rudolf in Kenya.

Among supreme predators, the great white shark gets much fanfare, but to those who know it, the crocodile is most dreaded. Both are ancient animals, having changed little since prehistoric times. The great white, however, is a deep-water predator. You pretty much have to be out there looking for one to provoke an attack. With the crocodile it’s a little different. Enter almost any African inland water, deep or shallow, and he’ll generally find you. Even if you make it to the other side you are not necessarily safe. The crocodile is amphibious. Simply being near water can get you eaten. Native Africans, especially women washing clothes or fetching water, present the easiest opportunity. Basking crocodiles often appear lethargic and slow-moving, yet they’re able to instantly extend their legs and reach speeds up to 30 miles-per-hour for a short distance. Crocodile victims seldom see the one that takes them.

Don’t get cocky if you’re in a boat, either, unless it’s a very large one. In his book of African exploration, Hearts of Darkness, Frank McLynn writes of a crocodile that attacked a vessel of six-and-a-half tons. As for native canoes, there are more documented cases of attacks than can be counted and possibly a hundred times more that have not. Equally numerous are hands, arms and feet trailing over the gunnels that have been snapped off as well as entire men neatly snatched from their seats.

We’ve all seen the documentaries of lions singling out a migrating zebra or wildebeest. There is the sudden burst of speed and a dramatic, even sporting, pursuit, to the point where one finds oneself actually cheering for the lion. Nobody ever cheers for the lizard-like blur that clamps down on the muzzle of a watering gazelle. There is only a brief soundless (if we’re lucky) struggle of staggered legs and flying water. Crocodile attacks are highly efficient, but they are never exalting. It’s like watching an animal going down a garbage disposal.

Crocodilians are the only order of survivors from the Archosauria group, which ruled the earth during the Mesozoic Period. In the last 200 million years, the order has changed little relative to other animals. However, the modem crocodile is really small in comparison to its early ancestors. Deinosuchus was a 30-footer that lurked in the shallow water over much of what are now the Americas, and Phobosuchus, the granddaddy of them all, exceeded 45 feet and weighed about 15 tons. Both critters lived during the Cretaceous Period, the heyday of the dinosaurs, and it is supposed that the Phobosuchus actually preyed on dinosaurs. I’ve seen the skull of a Phobosutchus in New York’s Museum of Natural History. It was found in East Texas in1940 and measures six feet long and about 3 1/2 feet across. The word frightening doesn’t even apply. Phobosuchus clearly had to have been a virtual monster.

Today, there are over 14 species of Crocodylidae. Most are tropical animals inhabiting the Southern Hemisphere. Because it has the widest range, the American crocodile is probably the best known. Found in brackish waters of Florida, the Caribbean and Central and South America it rarely exceeds 13 feet in length. The Nile crocodile, crocodylus niloticus, once ranged throughout Palestine and Egypt, and is still found throughout much of Africa. Largest and most fierce is the Indio-Pacific, or saltwater, croc of Crocodile Dundee fame. Known for their voracious appetite, many over 20 feet have been taken by hide hunters. Like the American crocodile, they are now protected and, therefore, are not hunted.

Characterized by its long reptilian head, the crocodile differs from our American alligator by a pointed rather than rounded snout. Having 64 teeth, the croc is constantly in the process of replacing lost ones and it will grow about 45 sets in an average lifetime. Also, on either side of the jaw, its fourth mandibular tooth protrudes upward rather than fits into the upper jaw. This difference can be seen clearly when the crocodile closes its mouth. As the lower jaw beneath the eye is upturned, the countenance resembles a sinister smile.

The croc also grows quite larger than the alligator. A crocodile killed in Tanzania in 1905 measured 21 feet and weighed over 2,300 pounds! More recently, one taken in Uganda was 19 1/2 feet long with a 6 1/2-foot girth.

In their several-year study of the large crocodile population around Lake Rudolf, Kenya, Alistair Graham and Peter Beard measured over 500 specimens taken for research. They found the growth rate for crocodiles to be extremely high in youth to adolescence and slower in later years. Like many animals, crocodiles keep growing until they die, though the greatest growth in old crocs is in their weight. Because of their tremendous number at Lake Rudolf, the crocodiles did not grow quite as big as in other areas; thus, the world’s largest are generally found where populations are smaller.

Graham and Beard found it difficult to determine the exact age of crocodiles. They surmised that about 40 years was the upper age limit for most of the Lake Rudolf population, but that certain animals could live as long as 70. The oldest croc ever recorded was a zoo-kept specimen of 50.

As with most crocs, those in Lake Rudolf prey mostly on fish, especially the large Nile perch which runs to several hundred pounds. Elsewhere in Africa, rivers and waterholes provide a steady supply of drinking and crossing animals, both wild and occasionally domestic. Waterholes are the ideal setup to take grazing game. The unknowing animal bends to drink and the waiting croc lunges, swiftly clamping down on the prey’s muzzle and dragging it into deeper water to drown. The enormous conical teeth make the hold inescapable. Lacking grinding teeth, the crocodile rolls quickly, tearing off limbs and chunks small enough to swallow. The crocodile is also adept at using its tail either to sweep prey off a riverbank or to corral fish in shallow areas where they become easier to catch.

The crocodile’s land prey can be anything up to the size of a giraffe, but buffalo and young hippos are quite common. If the skin is too tough for the crocodile to break, he will store it in an underwater cache until it rots sufficiently to be consumed. At a game crossing on Kenya’s Mara River, Leonard Lee Rue witnessed so many wildebeests killed by the crocodiles that they couldn’t eat them all.

On my first African safari, I was amazed to discover that even the smallest waterhole can support a croc or two. One afternoon I snuck up on what looked like a puddle of about 10 feet across and possibly 18 inches deep, where two reptilian eyes and a mean little snout faced the other way. I took a picture. At the sound of the shutter, the water erupted so quickly I nearly fell over backwards, but not before I snapped another. I have the photos next to each other in an album. One of a puddle with bumps, the other of flying water and angry crocodile. Small water, small croc. I concluded, but after that I gave even the smallest ponds ample quarter.

Crocodiles live where they make their living best, be it fish, fowl or migrating plains game. If the food source dissipates, they will attempt to move, though they must make it to another waterhole before the sun can parch their skin. Their bulky bodies build up tremendous heat, and a frequent sight among river travelers is the rows of crocodiles basing on shore with their huge mouths agape. This is not a threatening gesture, but serves to dissipate body heat like a panting dog.

Among Graham and Bear’s many experiments were attempts to trap crocodiles alive. Underestimating their tremendous strength. Bear purchased a shark net. If the net could hold 500-pound sharks, he deduced, it could do the same for crocs of equal weight. On their first try, several medium-sized specimens quickly tore holes and escaped. “It might have been a spider’s web for all of the trouble these crocs had tearing their way loose,” Bear lamented.

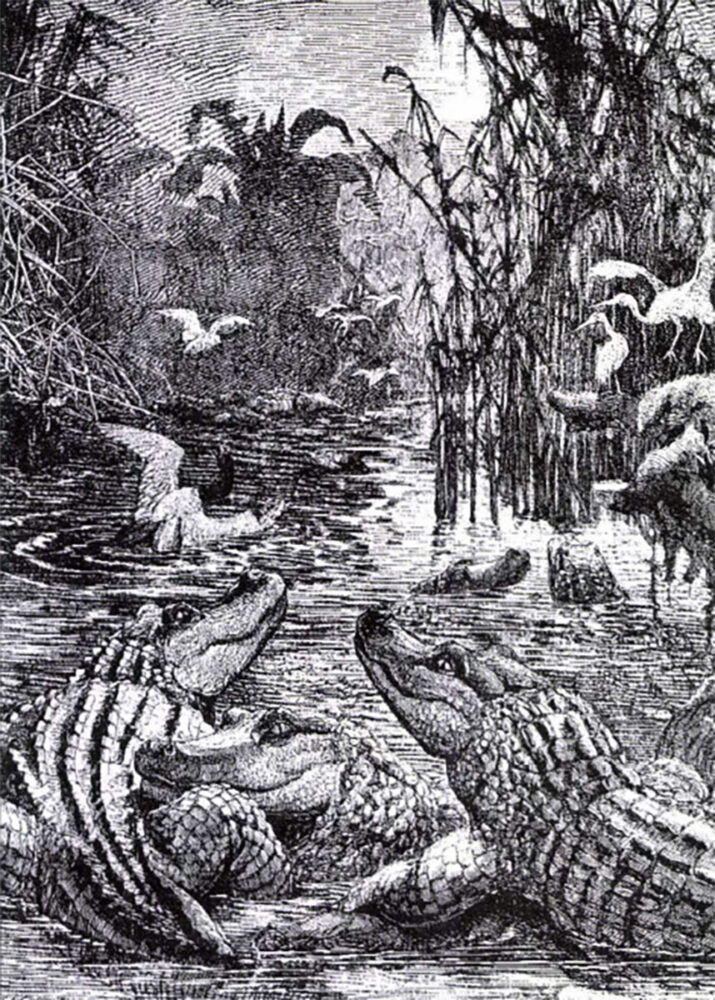

Sketch of crocs.

The crocodile’s raw power is astounding. And he is absolutely fearless. He has little reason not to be, having no other animal as a natural predator. The lion, formidable alone, often hunting in groups, yet the crocodile seldom finds it necessary to team up with another croc. Certainly, frenzies occur similar to what Le Rue witnessed with the crossing wildebeest, but Graham and Beard saw curious little competition among crocodiles for prey. The crocodile is basically a solitary predator and seldom fights with its own kind, even over a mate.

Most crocs breed near the end of the year, with the male performing ceremonial courtship maneuvers as he approaches receptive females. Once bred, the female will eventually build a nest and lay her eggs, seldom venturing far away. This is possibly the phase at which many boats have encountered unprovoked attacks — by protective mothers. After hatching, she will continue to guard her young against predators, including adult crocodiles, for two more years.

Sexual maturity comes between eight and 10 years. Gender is indistinguishable and can only be determined by probing a specimens underside. Unique body features included eyes set high on the head and a valve that prevents water from enter the nose — both enabling the crocodile to remain almost entirely submerged until a meal presents itself. Their sense of smell is exceptionally keen as is their vision both in and out of the water.

As adults, Nile crocodiles live in large communities of up to a hundred animals. In recent years many crocodile attacks have been in lakeside areas where the man population is growing ever closer to the crocodiles. Incidents on Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest freshwater lake, occur frequently. In March of this year, after 40 people had been killed over a seven-month period, the Uganda Wildlife Authority began an operation to cull predatory crocs on their side of Victoria. In the narrow country of Malawi, east of Zambia, BBC News once reported that crocodiles protected by the CITES treater were killing at least two people every day! The survey found that the dramatic increase in crocodile numbers had depleted the animals’ usual food sources, causing much greater predation on humans and livestock. The survey pointed out that it is likely the death toll is even higher as fatalities had become so commonplace that people no longer reported them to authorities.

The most devastating crocodile attack in history was not in Africa, but in Burma by saltwater crocodiles. Toward the end of the Second World War, British troops cornered about a thousand Japanese soldiers on Rare Island. The Japanese attempted to escape through the swamps. Many were already wounded and the smell of blood was heavy in the mire and mangrove thickets. As the tide began to ebb, the crocodiles moved in among the struggling men. It is likely the crocodiles had become accustomed to the sound of gunfire, associating it with corpses, and were summoned by the shots. In the morning only 20 of the original thousand Japanese were left to surrender to the British. That night of February 19-20, 1945, marked the most harrowing and deliberate attack on humans by animals of any kind.

Early books on Africa are replete with drawings of Nile crocodiles attacking luckless natives.

Probably the first commercial hunter of Nile crocodiles was the restless son of a South African tobacco farmer. Just returned from World War II, Bryan Dempster was assured a decent living on the family kraal an had recently married. Years earlier, as a boy of only eight, he had killed a crocodile on the Zambezi while hunting with his father. One evening they had heard a tribesman’s story of losing his wife and nursing child to a big croc at the river’s edge. They decided to hunt it. They shot a hippo to serve as bait and slept on the riverbank less than 20 yards away. Father and son woke to a loud thrashing as two pairs of 12-footers ravaged the carcass. The hunters slipped silently to the river, closing within five yards of the ruckus. Thrilled beyond all he could imagine, young Bryan and his father watched for 10 minutes that which few humans had ever before witness. A feeding pair would seize the hippo and somersault backwards, tearing chunks loose and devouring them with a series of swallows as another pair moved in to feed. There was no fighting among them, just a morbid reptilian ritual of waiting, moving in to feed and retiring back to consume. Shivering with excitement, the boy moved closer and, at his father’s cue, leveled his old 303, nearly touching the muzzle to a croc’s head. Father and son fired simultaneously, and both were splashed as two crocs reacted, slumped and died.

The memory of that night never left Bryan. He announced to his family and new bride the he was headed to the Zambezi to hunt crocodile skins for the market. He purchased what equipment he could afford in Durban and set out in December of 1947 along with two good Zulu men: Joseph, his best friend since childhood and Josephs cousin, Albaan.

It was tough going. Bryan’s first mistake was to start at the height of the wet season. Rain and wind pelted their small boat in a storm and the swollen river grew rough. Trying to make it to shore, they ran aground on a submerged sandbank. Joseph and Albaan jumped over to push while Bryan steered. Instantly Joseph was trapped in quicksand and nearly sunk from sight. Bryan and Albaan were just barely able to pull him out and the expedition finally made it to the riverbank.

When the weather cleared, the men were encouraged by the number of crocodiles they began to see, but efforts to shoot them from the boat proved useless. The crocs simply slid into the water before Bryan could speed close enough to shoot. He tried to stalk them on land, but even after crawling through available cover and heeding the wind, he was only able to get within 200 yards or so — too far to hit the vital brain. The rain started again. There were clouds of gnats, endless stalking and poor meals. There was failure after failure. Then Bryan came down with typhoid. It took him two weeks in a Livingstone hospital to recover. During that time he realized that hunting by day was pointless; the crocodile had to be hunted at night.

His hunting then began a new challenge of navigating the Zambezi in darkness. The river meandered sharply and the narrow channels twisted through it like a maze. Sandbanks stopped the boat and sheared propeller pins. The men learned to follow the reeds along the liver’s edge and, as their night experience grew, Bryan began to take crocodiles, chilling close as he found their eyes in his lamp. The group was harvesting about three crocodiles each night until a rogue hippo attacked the boat, crushing it to pieces and turning to kill Albaan in his massive jaws.

Nearly wiped out by the hippo attack, Dempster was determined to canyon. He sold his skins and purchased a Brno 8 x 60 rifle, more powerful than his old 303, and an aluminum boat. Bryan and Joseph set out again for the river, this time to where Dempster had heard there were many crocodiles in the 300-mile stretch from Victoria Falls to the Mozambique border.

It was this second expedition where Bryan perfected his hunting method. He would bait the crocs with hippos as he had done with his father long ago. That way he could enlist the help of local natives who were given any leftover hippo meat. Dempster’s luck changed for the better and he began to take as many as five animals a night without peril.

Then, after a certain successful night’s hunt, as the men started back in the early morning twilight, Joseph whistled and pointed to the riverbank. There, sleeping, lay the largest crocodile any of them had ever seen. It seemed to be well over 20 feet! Bryan Signaled for Joseph to turn the boat toward the great croc. The wind was coming up and the river had turned choppy, but Bryan moved up to the bow and readied his rifle. No more than six feet from the tail, he aimed for the croc’s brain and squeezed. As he did, the boat’s bow rose slightly with a wave, causing his bullet to miss the vital spot. Poorly hit, the croc reared straight up on its tail and somersaulted backwards. The men had no time to react and the enormous animal crashed down on the boat like a falling tree.

When Bryan regained consciousness, he was in the river, floating down a particularly fast area. Joseph was close by, his eyes wide with fear. The two struggled to a point of land and crawled ashore. The boat was nowhere in sight and all of their equipment was lost. The next day a Sena tribesman found the dingy, but the great weight of the croc had demolished it.

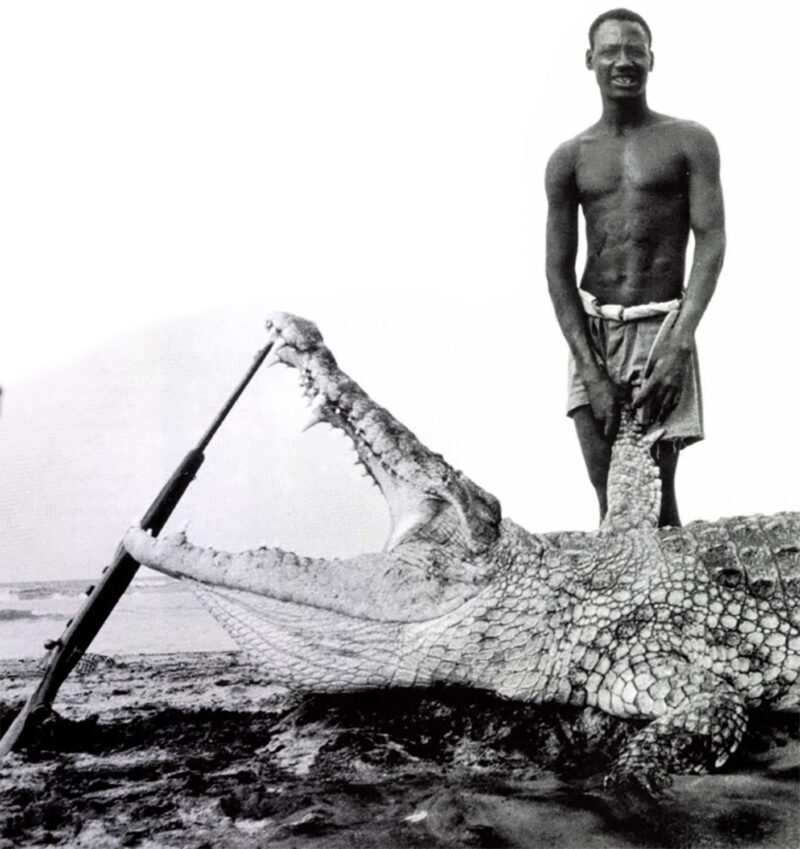

Sportsman Paul Hamner and his entourage of Zimbabwe trackers pose with the croc that wouldn’t die.

Again, Dempster reoutfitted and returned to the river. He even experimented with a metal trap which the crocodiles mangled to ribbons. There appeared to be no easy way, but he and Joseph had become skillful, drifting downriver to four or five hippo baits each night and taking as many crocs. In time the rigors of croc hunting took its toll on Bryan. Bouts of malaria recurred and rheumatic aches became constant. His shoulder was so chronically sore that he came to dread firing his rifle. Finally, with the help of a tannery owner, he began a crocodile farm to raise his own skins and gave up commercial hunting.

Today, sportsmen can hunt crocodiles in most countries of southern Africa. Usual methods are by opportunity when hunting other animals, by baiting, or from either a boat or blind. The SCI record is a I7-foot, 8-inch animal killed in Tanzania. An 18-footer taken earlier this year in Zimbabwe is currently pending approval for the new number one. Both animals were taken with a rifle. The present bow record is a I3-foot specimen taken in Zambia.

The crocodile can be a difficult trophy to kill. My friend, Paul Hammer, recently hunted one in Zimbabwe — an agonizing, two-hour stalk through swampland in which he, the PH and trackers crept barefoot to a secluded upwind pool where the biggest croc lay half out of the water. Paul squeezed off a neck shot — six inches behind the jaw — as instructed. Instantly, the croc swapped ends and submerged. Thinking the animal fatally hit, the PH suggested they wait a few days for internal gas to float the carcass back up. After the second day, to everyone’s amazement, the very same crocodile appeared in his former position at the edge of the pool. Except for the bullet slightly forward of the intended area, the croc appeared unaffected. The group repeated their long stalk, this time circling behind the croc, to where Paul was able to dispatch it with a brain shot. It is an exceptional specimen, all sleek reptilian lines and macabre smile — a truly fine representation of the world’s most deadly predator.

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now