Treat the earth well; it was not given to you by your parents, it was loaned to you by your children. We do not inherit the Earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children.

The woods are mostly silent now. As the old man’s boots disturbed the dry autumn leaves he listened for the sound of little foot falls rustling behind him, but there were none. Nor was there the expectant grasp of a young hand as he crossed a downed tree. Occasionally, he saw the telltale signs of his son’s youth spent in these woods, a stick fort slowly leaning back down to the forest floor, a rock cairn marking nothing in the middle of nowhere. There were also innumerable fire rings scattered around, which he mused would lead future archaeological anthropologists to conclude that these woods were once the winter encampment for a large band of Chippewa Indians.

Traveling farther into the woods, he saw the trees where his son took his first squirrels. With their backs pressed against a big red oak, Joshua fought to remain still as he searched the tree canopy for the slightest sign of movement that would betray the presence of his quarry. The young boy practiced all that summer with his little .22 caliber single–shot rifle until he became absolutely deadly with it. For several years thereafter, no squirrel or chipmunk was safe in those woods. Now, except for an occasional red-tailed hawk or red fox, they scurry across the forest floor and bare winter branches with reckless impunity, the danger of a little boy with a rifle having long since passed.

The Red Gods were kind to them that morning and his son took two fall-fattened squirrels cleanly with two shots. The taxidermy mount of those two animals, once a prized possession, now gathers dust on the wall of the empty cabin as they chase each other across a log in perpetuity. The little rifle rests unused and slowly rusting in the back recesses of a darkened closet, many years having passed since it last felt the grasp of little hands.

Just behind the cabin is the hill where his son shot his first deer. It was a sleek, well-larded spike buck that fell to the report of a Remington .243. The old man can still see the boy rushing to the downed animal and running his hands appreciatively over the warm chestnut colored fur with a look of pride and admiration. A thin cloud of steam, illuminated by the weak autumnal sun, rose off the animal and dissolved into the crisp air of an early November morning.

The old man reflected on having killed Cape buffalo and been less proud than he was at that moment. It was a rite of passage that has been handed down from father to son (and sometimes daughters too!), since time immemorial. The antlers from this animal, although covered now with years of accumulated dust and cobwebs, still occupy a place of honor along the rafters of the old barn amid all the other memories that are fastened there.

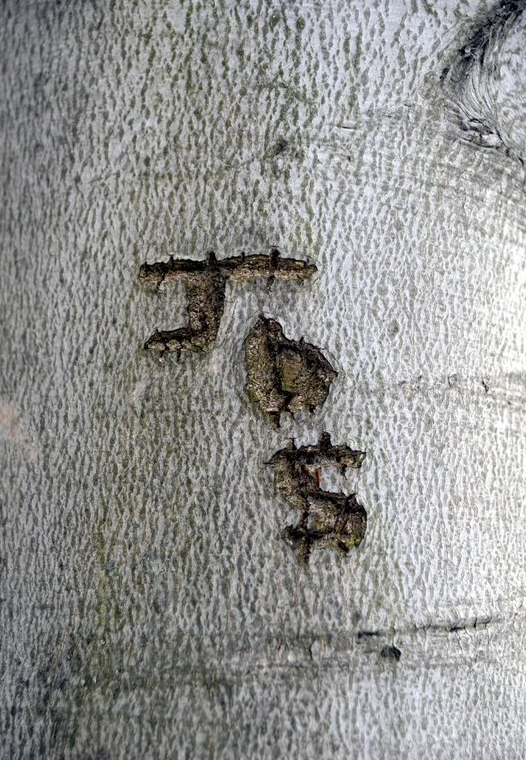

Occasionally, he still finds his son’s initials “JDS” carved into the smooth, indelible bark of a beech tree.

Occasionally, he still finds his son’s initials “JDS” carved into the smooth, indelible bark of a beech tree, the result of an idle moment and a sharp hunting knife. One such carving is up high, next to a tree stand overlooking Missy’s field. The field was first hunted by his daughter in her youth and he still referred to it by her nickname though she too has been gone for many years and now has children of her own. The tree-stand sits empty each season and quietly rusts away at the spot where his son killed his first deer with a bow and arrow. He was too little to drag the mature doe out of the woods by himself and too young to even think about suppressing his exuberance. The old man remembered the weight of the dead deer and standing shoulder to shoulder with the boy as they dragged the downed animal out of the woods together like two ill-matched draft horses.

Long before the forest that the old man knew and well before the primeval old growth forest that preceded them, there were glaciers here. The undulating topography of this land gathers its character and features from the glacial till left behind as a succession of glaciers receded North tens of thousands of years ago. Even now, these hills make the most stalwart grouse or woodcock hunter earn each bird and every successful deer hunter contemplate the value of packing a knife and fork with them. For the old man, those hills seem to rise more steeply with each passing year and he knows the time will soon come when he can no longer negotiate them.

The woods have changed dramatically over the years. Back in the 1870s, the old growth forest sounded with the rasp of the crosscut saw and falling timber. White pine was king and old growth forests with 200– and 300-year-old trees stood nearly 200 feet tall. Narrow gauge rails snaked the heavy logs through the forest to the riverside banking grounds where log drivers herded the immense logs along spring-swollen rivers to the sawmills waiting at the mouth of the river. Buried deep in the forest loam, the old man still occasionally finds long since forgotten pieces of logging chain, broken saws and twisted railroad spikes, the latter were left there when the rails were reclaimed and laid elsewhere in another stand of virgin forest. Here and there he can still find the weathered gray stumps of these trees, sawn off about three feet from the ground, their presence a final but vanishing testament to that time in history and a reminder that these woods were once very different from what they are today.

Not long after the last white pine tree fell, the barren landscape was pressed into growing potatoes. Piles of field stones run in lines throughout the woods now marking what were once the edges of those potato fields. Each spring, frost-heaved stones were pulled off the fields by hand and carted to the wood edge using teams of well-muscled draft horses. The stone house, which resides in the old orchard, is similarly made from those stones.

The young boy practiced all that summer with his little .22 caliber single-shot rifle until he became absolutely deadly with it.

The potatoes were grown throughout the great depression and, together with what game could be harvested from the new woods, kept many a family from going hungry in these parts. In later years, they also ran cattle through these woods and the old man could still make out the rusted ends of barbwire fence sticking out of the middle of large trees that were once mere saplings when they served the purpose of a living fence pole. In time, it seems that nature reclaims everything and eventually smooths out the insults that man has put upon it.

In the spring, the sugar maples were tapped, and the sweet watery tree sap rendered into maple syrup and maple sugar in large cast iron kettles suspended over burning logs. The largest maple trees still bear witness with a ring of tapping scars buried deep in their cortical wood. The old man still gathers sap each March and tends the wood-fired evaporator alone, and he welcomes the heady aroma of sweetening sap tinged with the smell of wood smoke because it means that spring is approaching — just as surely as the tangy aroma of frost–kissed leaves means that autumn is once again upon us.

In the closing years of his boy’s youth, before the competing distractions of high school friends, cars and the lure of the fairer sex took precedence, the old man and his son hunted together a lot in these woods. Although there were other trips to places such as North Dakota for pheasants and ducks, and Wyoming for deer and antelope, these woods and this land have always been their home and the place they yearned to return to each fall. The coming of college brought with it increasing responsibilities and the demands of adulthood. Other distractions and obligations took his boy far away from these woods and opened up a world well beyond the confines of their diminutive boundary markers.

The old man hoped that he had managed to instill in his boy a strong sense of values, a love for all things wild and an abiding sense of stewardship to the land — things that he could carry with him regardless of where he traveled in life. Perhaps in time, the boy will return to these silent woods once again and pass along those same values to his own children. In the end, we never truly own the land, we are only temporary stewards and are responsible for protecting it, improving upon it and handing it down to the next generation. Although time with his son in these woods has now largely passed, each fall the old man returns to this land to seek out the places and memories of those seasons he shared with his son and observe the mute talismans from times past.

There was an age, a space of innocence, freedom and fascination, where every day brought another revelation, and tomorrow could never come fast enough. When, as boys and girls, we learned as much from woods and waters as from a spelling book.

There was an age, a space of innocence, freedom and fascination, where every day brought another revelation, and tomorrow could never come fast enough. When, as boys and girls, we learned as much from woods and waters as from a spelling book.

Most of all, there were moments of infinite beauty and sharing, when someone laid a hand at our shoulder and led us there. So that later we might lead another, in turn.

Here, in parables of incomparable warmth and intonation, the author of the celebrated books, Jenny Willow and Zip Zap, Mike Gaddis, explores the enchanting realm of outdoor mentorship. Not only in kind and gentle remembrances, but in intuitive vignettes, present and future.

Legend’s Legacy stands unparalleled as an affecting commemoration of the most endearing aspects of our sporting traditions—an inspiring tribute to those who cared, who taught us then and guide us still.