Folks talk about it still.

The nights were the blackest anyone could remember. But there was not a star in the sky. Mountain hollows rang with banjo music. Yet, no one could be found. Each evening at midnight the bell at Humphrey’s Chapel tolled … the rope left swinging … and not a soul was there.

Then the world hushed. The wind died. Birds forgot their song. Creeks hurried over the rocks, as they had a million years, yet there was no sound of their passing.

Mae Kegley, coming 103, recalled that her grandfather had spoken of a similar occurrence when she was a girl. The old man had called it “a silent spring.”

Mae Kegley, coming 103, recalled that her grandfather had spoken of a similar occurrence when she was a girl. The old man had called it “a silent spring.”

On — for five nights and five days — it continued.

Until, upon the evening of the fifth day — March 3rd, 1890 — William Helems, postmaster of the small, local village of Paint Bank, Virginia, reported the strangest of all: “Three suns, standing in the evening.”

One-hundred-twenty years later here I was, on the steps of the General Store in the same tiny village, treating myself to an RC Cola and a Moon Pie … wondering … was it happening again?

I was turkey hunting, easterns in the Alleghenies, with Josh Duncan of Potts Creek Outfitters, and for three days — despite our every effort — the hills had been silent as the gravestones on Hollow Hill.

It was the tag end of the season in the Virginias, and I was working territory in both states. A matter of convenience, levied by the War.

The Civil War, the only one still viable in this quaint corner of the Commonwealth. The fierce loyalties had split Old Virginia, leaving Paint Bank just three miles east of the new western territory — which went Federal.

A latter-day Confederate, I was hell-bent for a gobbler about these same, glorious hardwood hills. Not a tom of either persuasion talking, to even know one was there. Tongue-tuckered and petered-out, they seemed, hen-whipped and utterly uninterested.

But I’d not quit.

Paint Bank hadn’t, when it could have. Here it was still, in the gentle Valley of the Greenbrier, between the tall shoulders of Peters Mountain just north and Potts Mountain south. Named for the “Painted Banks” of Potts Creek, which had afforded the Cherokees war paint and pottery.

In 1881, 16 years after the War, the pioneering English, German and Scots-Irish families that had arrived here in the1700s had not only scratched on, but recovered admirably.

An agrarian and lumbering existence sustained the village happily into the early 19th century when the discovery of major deposits of iron ore and manganese rendered it a boom town. Twenty years later it all crumbled to dust.

Paint Bank faded, failing to recover until restoration projects were mounted in the latter 1990s, on the dream-wish of John and Nancy Mulheren. The very quiescence of this tiny and historical Allegheny village had saved it to become what it is today … a decently faithful re-creation of what it was. A crucible of quaint and rustic highland life and living, and about these grand and lovely hills, a bow hunting beckoning for spring gobblers and white-tailed deer.

I had not counted on the silence.

Hopes climb high, high as these old hills, on the onset of a good hunt. I was freelancing, Josh dropping me out in promising places, for he knew the land, and the travel of the birds. The rest up to me.

The first afternoon, an hour after I got there, he suggested a Virginia set-up, a remote chufa patch above a grassy pasture bordered three sides by roosting and foraging corridors.

I sneaked in, stuck out one of Josh’s mounted hens.

An afternoon hunt late in the season, I didn’t expect a gobble. What I did expect was a sly, old limb-hanger to come pecking nonchalantly along the edge of the woods, bidding his way to roost. So I clucked-and-purred along — like a happy hen or a kitten in a rug — to beg his attention once he arrived.

It was quiet. Dead quiet.

An hour wore on, then two, then three. The slanting rays of the falling sun were filtering through the timber, spilling in pale, broken patches upon the field.

The decoy looked lonesome. I ventured a few soft, desperate yelps.

Nothing. Not a hen. Not a squirrel. Not an owl, as dusk fell.

“Only the first afternoon,” I agreed with Josh. “Morning would bring better.”

“Only the first afternoon,” I agreed with Josh. “Morning would bring better.”

It did. A beautiful West Virginia dawning and a resplendent highland sunrise. Pink, and gold and lavender.

I was high on a knob, by a little green clover field, and all around the dawn-gray ridges swelled.

“A favorite place for birds, “Josh had declared, “but cagey old rounders. There’s some four-year-olds in there that’ll make your rudder flutter.”

The kind I love to hunt.

But the cardinals should be waking, and they weren’t. The wind should be teasing the silver leaves, and it didn’t. I had listened painfully for a bird to open since bare dawn — I could hear forever that high — but the morning was mute as a millstone.

All morning I laid out a random run of yelps, an occasional lost hen call . . . then got plumb mad and threw down a bunch of get-in-here-and-have-me cutts that knocked bark off the trees.

Thinking to see one of the Ol’ Boys, blown out like an oil drum, sass-shaying his way down the path with his tongue hanging out. Or he’d just be there, all of a notion, before I knew it.

Instead, it got hotter, and brighter and quieter.

I don’t move much . My favorite poison, if a bird is known to the area, is to work and wait til I get him in. Jobe set the standard, and I’m not far behind. It’s a matter of pride.

“Don’t come back ’til two,” I had told Josh. Ten-to-two, you can often coax a know-better, hen-dumped Tom-of-the-Woods into a blathering,“ hang-on, pretty-britches, I’m a-comin’” barnyard fool.

Not today.

Josh was in disbelief. “You didn’t hear nothin’?”

I shook my head.

“Be damned,” he muttered.

“That’s what I said,” I told him.

I hadn’t borrowed time to eat, so we subtracted an hour for lunch. Chewed a sandwich and sipped a grape Nehi by a delightful, little butternut walnut grove. By a clean little stream overhung with orange mountain azalea, the mood timeless as the hills. I lay on my back under a big oak, the clouds drifted lazily by, buzzards circled, and I thought how much I love mountains.

I hadn’t borrowed time to eat, so we subtracted an hour for lunch. Chewed a sandwich and sipped a grape Nehi by a delightful, little butternut walnut grove. By a clean little stream overhung with orange mountain azalea, the mood timeless as the hills. I lay on my back under a big oak, the clouds drifted lazily by, buzzards circled, and I thought how much I love mountains.

By three, though, I fretted to go.

“I got just the place,” Josh allowed. Turned out, he didn’t. The sum of it, come dark, was dark.

“Be damned,” Josh said again.

The buff-a-loaf, with some sweet-little-granny-woman kind of tomato sauce — sweet potato fries on the side — sure was good, there at The Swinging Bridge Restaurant in the hack of the General Store. The Mulherens have revived buffalo here, too, on Hollow Hills Farm.

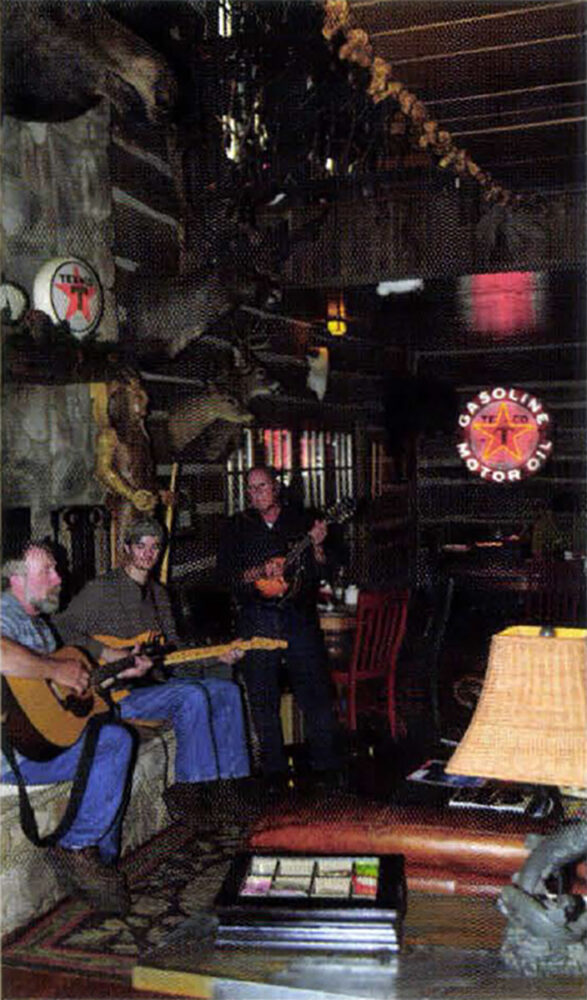

It was Thursday night, and a bluegrass band cut-a-rug before the fire. Sweet tea and toe-tapping helped our meal down. Afterward, I had a fudgesicle, like I used to when I was a kid, cause they still sell ’em here. Along with Winchester turkey loads, right there with nine kinds of chewing tobacco. A mite past that wooden tub of iced-down eight-ounce Cokes, orange Nehis, Dr. Peppers and R-a-Cs.

The turkeys weren’t talking, but we shore was eating good.

The old Norfolk & Western RR Depot, circa 1909, serves as the lodge for Josh’s operation, just across the road from the General Store. Restored to its original, white washed, board-and-batten glory, the decor is rustic antique, and a good bit of Paint Bank nostalgia adorns its walls. It’s a happy place to stay, within a stone’s throw of Potts Creek.

The little town bustles on weekends, but still looks and feels right, managing a bygone feeling that hasn’t caught up to the times. The last morning I was there, a Plott hound came ambling down the street by the General Store, and folks were watching for him. That set about right with me.

Back in my room, though, in The Depot, I began to doubt myself. Two days into the hunt I hadn’t raised a bird. Hen or tom. I by to think I’m better than that.

The third day, I tipped in and settled long before light. On another clover field in West Virginia. Josh was exhausting his prized places. I gave it my all.

The morning was somber as a wake.

Turkeys can beat you in the ground. And stomp on the hole.

At noon, Josh was incredulous. “Nothing?” he said.

Josh is a relocated Georgia boy, as patient and unperturbed as red clay. But it was getting to him, too. He didn’t know whether to doubt me, or the birds.

Neither did I.

Thing was, he was hunting first light with other clients. Same deal. Maybe a single, distant gobble, but then, endless silence. Evenings, we tried hard to roost a bird. They wouldn’t speak.

Josh had glassed one tom the day before. From the main road. At three o’clock he was pecking up grit, along the bottom of the steep, green pasture behind the buffalo barn.

An afternoon later I waited for him. One o’clock on. Finally, a hen, at four. I clucked to her, kept her handy. At five, the gobbler crossed 200 yards up the hill. I purred like pleasurable sin. The hen pecked around.

He stared, half-heartedly strutted, wavered four times. Then sallied on. My God …

On it continued … the deathly quiet . . . until it was deafening. Until the quest became grueling. Bed at ten, sleepless til twelve, up at three. Day long-gone, and too damn tired for a shower between.

Nothing was working. The birds were frigid as an icicle.

Frank White, who helps Josh, is a veteran West Virginia Wildlife Officer and a savvy and able man. He had a corridor he’d scouted in the woods. Between feed and roost. Thick with sign.

We agreed it was worth the try.

But I worried. All seemed a rut, and tomorrow was the last hurrah, the last day of the Virginia season. I needed some thin thread to hang a hope on. The pasture behind the buffalo barn was speaking to me.

“Before we go,” I told Josh and Frank, “I want to put my blind in there, top of the hill, along the woods-line.”

Afterward, it was a long, sweaty climb to the wooded ridge Frank had scouted. By two I was set. Then the sun dwindled. The sky soured. Thunder grumbled in the distance, beneath the monotonous stillness.

I kept clucking … wishing …straining … for a bird to work up the slope through the timber.

At prime time the storm broke. Lightning sizzled, the ground shuddered, thunder thudded like cannon fire. Then came the rain, indriven, drenching sheets.

Broken at last, the infernal silence. Whether there were three suns, it was impossible to tell.

Another brief, sleepless night. I tossed and turned, didn’t want to leave beaten.

Josh dropped me at the pasture, just behind the bam, two full hours before dawn. ”I’m dead-bone tired,” I told him, “I’m staying in here til three. At three, it’s over, do or die.”

I made my way in a trickle, through the black dark, to my blind at the top of the hill. On my back were my three Dave Smith decoys. As quietly as molasses crawls I laid out my favorite set: a hump-backed jake over a submissive hen, with an upright, on-looking hen ten feet to the side. In a bare spot, ten yards off the fence line.

Thirty-nine hours I’d spent on a turkey set, in three-and-a-half days. Regardless of what happened, I’d wager ten more. Some time, someway … I was counting on a bird working through.

It’d been hard. But I had a feeling.

I settled in, readied my bow.

Until eight o’clock, I did nothing but listen. As mightily as I could.

Nothing. Nothing but the sound of silence.

One call — one only — I allowed myself, on the half-hour. A soft, teasing run of yelps here, a mildly aggravated spurt of cutts there.

On wore the morning, long and still. Ten-thirty. Eleven. The thought of losing was looming tough to bear.

The morning air was clean, the sky egg blue, the sun deepening the colors across the valley. You could see the cap of Peters Mountain, the new green on the oaks.

Eleven-thirty … eleven forty-five.

Nothing. Just the hush on the hill.

One last card, and the time had come to play it. I had set it up, waiting all morning toward the moment, stalling 50 minutes since last I’d called. Violently, I shattered the stillness with a short run of cutts, then picked up my gobble call. Following a slow ten count, I rattled it just as absolutely hard as I could.

Obbble-obble-obbble! Obble-obble-obble!

Holy Jesus. At long, merciful last. Not 60 yards above, in the woods. I answered with a few excited clucks.

Obbble-obble-obble. Obble-obble-obble.

Grits and Glory.

He must have gobbled 60 times, closer and closer. Coming. I shut up, had the bow on my knee. Fifteen minutes … twenty. Silence again. Thirty …Then a muted gobble from where I’d first heard him. He was leaving.

Good God . . . not after all this.

I cutt at him. He boomed back, drifted closer, then away. Fifteen minutes of dueling, the gobbles gradually more distant.

One gamble left, a huge one. I hit a few cutts … sharp enough to clip limbs off the trees, then unlimbered the gobble call again. One-one-thousand, two-one-thousand, three- . . . on ten, I hit it as hard as I could.

Obbble-obble-obble! Obble-obble-obble! Back rattled his livid retort.

Another ten count and I laid on the gobble call again, then squealed, like a bird got here before him … jumping on his hen.

He stormed the woods down, raised the hair on my head.

Then total silence … I’d utterly blown it … or he was here.

I had the bow up … waiting. the seconds dripping by like pregnant raindrops.

Then I heard the fence wire sing, and there they were. Two huge longbeards, heads red as blood. I made my move Swiftly, drawing as they hunkered down, sneaking in on the jake. They meant to flat-ass kill him.

The arrow took the front tom hard through, and all of a moment came a wash of reality, an incredible relief. He was down flopping while his long-bearded companion catapulted skyward, beating his way up over the trees and far back into the woods.

There he lay. Inch-and-an-eighth spurs, beard about ten-and-a-half inches. One hard-won bird.

I sat alone on the hill a long time. An old pickup pulled in behind the bam, far below. Somebody sitting, bucking atop something, in the bed. Later, Aaron Calvee, a good-oI’, mountain Plott hound man, came jouncing up to get me.

I sat alone on the hill a long time. An old pickup pulled in behind the bam, far below. Somebody sitting, bucking atop something, in the bed. Later, Aaron Calvee, a good-oI’, mountain Plott hound man, came jouncing up to get me.

“I’d a-been he re sooner,” he said, “but I’s sittin’ on a buffalo calf.”

“I didn’t need sooner,” I told him.

Together, we took stock of the gobbler.

“Does this p lace have a name?” I said, after a time.

He thought a moment, smiled. “Cemetery Hill.”

“I’ll be damned,” I said.

I leaned back against a tree. Aaron against another.

The breeze withered in the tops of the trees. The rustle of the leaves died. Soon, it was graveyard still again.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now