He had it all – money, education and looks – along with an obsession for danger that would get another man killed.

He was a millionaire, Arctic explorer, big game hunter and movie producer – a man who was larger than life in everything that he did. Born September 18, 1877, Paul J. Rainey amassed great wealth from the coke and coal mining industries that were so crucial to the industrial development of the United States in the late 1800s. Standing 6-foot 4 inches, Rainey was the playboy with it all – education, money, looks and a taste for danger.

As diverse as his interests were, Rainey had two that defined his life and legacy – hunting and photography. One story has it that after attending the National Bird Dog Field Trials, Rainey was inspired to begin assembling an 11,000-acre parcel of land in northeast Mississippi. Whether that story is true or not is uncertain, but what is known is that by 1901 Rainey was in the process of creating an estate that became his home and hunting preserve.

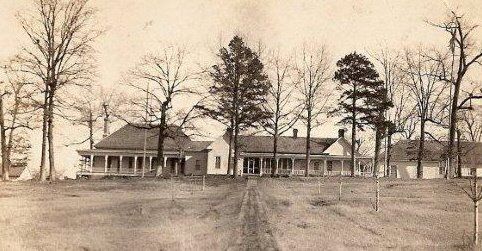

Tippah Lodge

Rainey eventually controlled more than 30,000 acres in Tippah and Union counties and stocked his land with bear, fox, pheasant and wolves. On one tract he transformed a small house into Tippah Lodge, which he expanded to 23 rooms including nine bedrooms, dining facilities, living rooms, a billiard room and an indoor heated swimming pool.

Surrounding the house, Rainey constructed fishponds, a sunken garden, a round polo barn designed to hold 50 horses and a special kitchen just for his hunting dogs.

The arrival of Rainey in Tippah County was certainly one of the greatest economic development events ever to occur there. Rainey ended up owning a bank and constructing the area’s first garment, soft drink and ice plants. To provide for the overflow of guests at Tippah Lodge, Rainey built a luxury hotel complete with Italian marble floors and a European chef. In front of the estate, Rainey constructed a railroad siding and station to accommodate his private Pullman car.

Tippah Lodge was home not only to Rainey, but also his bird dogs, fox and bear hounds and eventually the dogs that he used to hunt lions in Africa. E.M. Shelly was Rainey’s head dog trainer, and a man who became famous in his own right. The author of a number of books on dog training, Shelly was inducted into the Field Trial Hall of Fame in 1957.

Inspired by Theodore Roosevelt’s much-publicized safari, Rainey developed a keen interest in hunting in Africa. By 1911 he had acquired a home outside of Nairobi as well as a cattle ranch at Lake Naivasha in the Great Rift Valley. He was also ready to try a new approach to lion hunting.

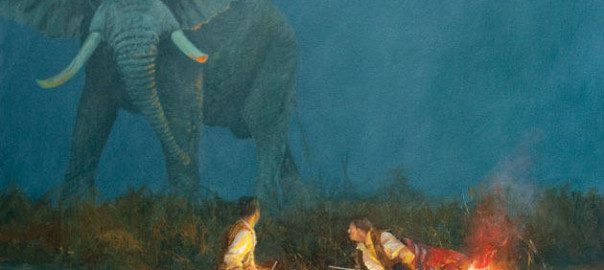

Although the use of horses to ride up game was not new to Africa, Rainey intended to add hounds to the equation and use them to bring lions to bay, a new and potentially risky undertaking.

Rainey began his preparations by importing packs of trained bear and cougar hounds from the U.S., with Shelly as their trainer. He also hired George Outram and Alan Black to assist him on his lion hunts. Outram and Black were both experienced white hunters and they agreed to sign on, although it’s likely that they had reservations regarding Rainey’s plans.

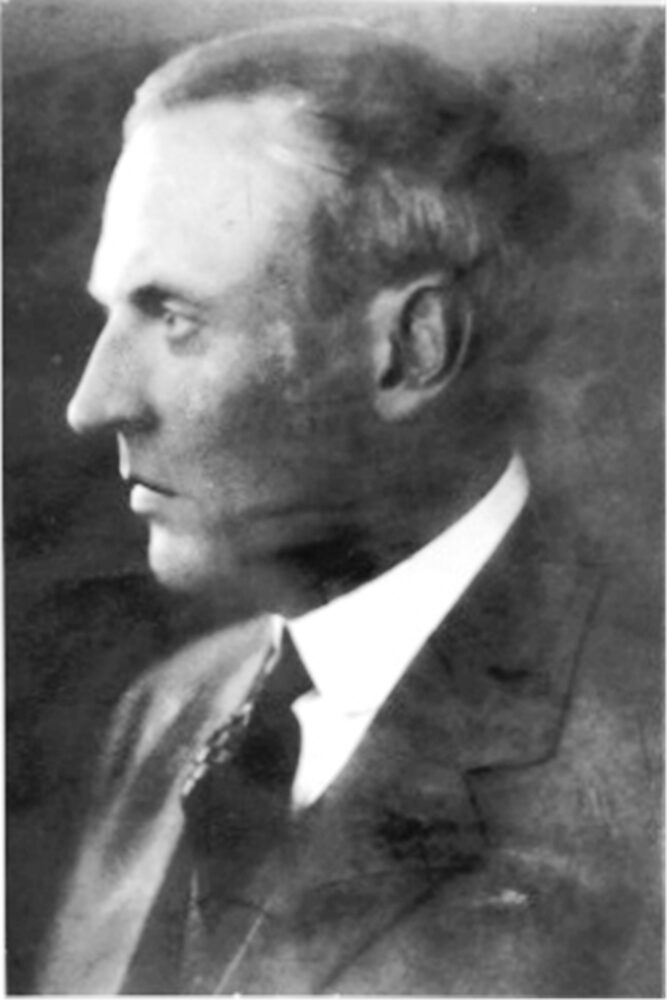

Rainey adorned in British hunting attire

George Outram came to Africa in 1903 with good knowledge of the border region between British East Africa (Kenya) and German East Africa (Tanzania). The second member of the team, Alan Black, had at one time been employed by Lord Delamere to control predators on his lands. In fact, Black may have been the person for whom the term “White Hunter” was created. As the story goes, Delamere employed two hunters for predator control, one was an Abyssinian and the other was Alan Black. Delamere, to distinguish between the two men, took to referring to Black as the “White Hunter” – and the term stuck.

Outram, in addition to his knowledge of the border region, provided another key element – lions to use in training Rainey’s dogs. Outram had lion cubs at his home and each day he led them to their food, which had been placed a distance from his house. The hounds were led after the lions so they could strike their trail and follow the lions’ scent while learning to ignore all other game. When the hounds were deemed ready, Rainey, with cameramen along to film the hunt, headed out on safari.

Eight days out, Black felt that they were in an area where a shot at a lion was possible. Early in the morning, he carefully positioned Rainey and his friend, Dr. Johnson, while Outram took a contingent of porters and formed a line to beat a hillside in the hope of pushing a lion to Rainey. The drive was successful, pushing two big cats to Rainey and Johnson who killed them. Rainey’s dogs were brought up to see if they would follow the lions’ trail and they did, straight to the dead cats.

The next day the process was repeated on another hill and again two large lions were flushed. This time Rainey and Johnson did not shoot, but instead followed the lions. One traveled about two miles and then turned to face his pursuers.

Black had Rainey and Johnson pull back and the lion then moved across a gully and joined the other lion. Rainey waited for Shelley to bring up the dogs, but in the process, Shelly crossed close to one lion, which rose up within yards of him. Shelly’s dogs saved his life. They immediately surrounded the lion and distracted it enough for him to escape and for Rainey to come up and shoot the cat.

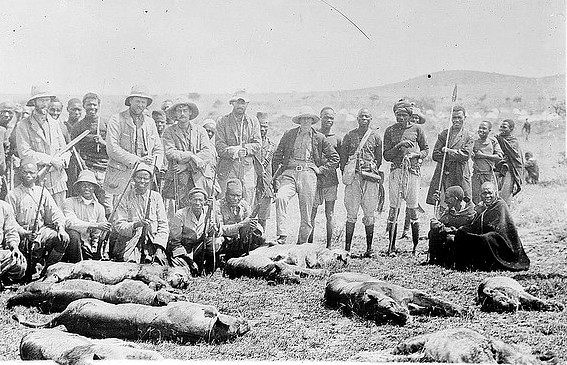

The dogs were by all measures a success, and Rainey and his party were able to shoot 27 lions in a six-week period. In total, Rainey reportedly killed 120 lions in 1911.

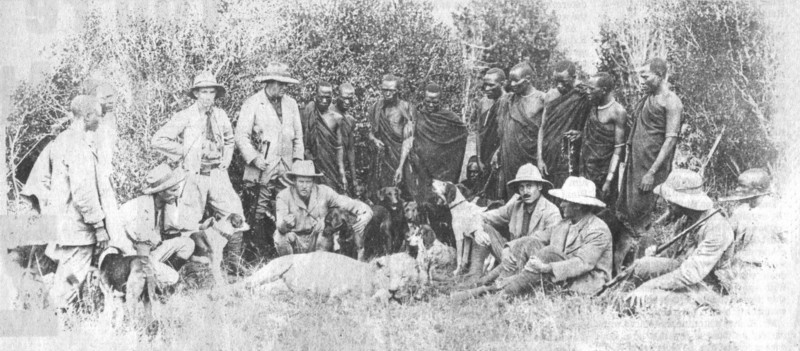

“Mornings’ work–killed in 15 minutes–Paul J. Rainey’s African Hunt. Photo: Library of Congress/George Grantham Bain Collection

To native tribesmen who kept livestock, the elimination of any lion was a good thing, yet there were those who criticized Rainey’s method of hunting. The number of lions killed raised concerns among some large landowners for, as Churchill noted, “Nothing causes the colonist more concern than that his guest should not have been provided with a lion.” Others felt that hunting with dogs was not sporting because the dogs were at risk rather than the hunter and that the hounds made it too easy to find and shoot the big cats.

Concerns also came from individuals who felt that the large-scale destruction of wildlife might cut into the revenues and jobs derived from visiting sportsmen.

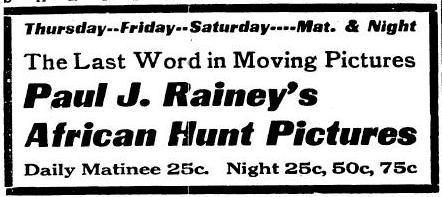

Although Rainey’s hunting method may have drawn criticism, the films he completed during his safari were a huge success. Rainey’s cameramen not only documented actual hunt sequences, but they also managed to film a great variety of African animals coming to waterholes in the arid region.

With 100,000 feet of accumulated film, Rainey produced a silent movie titled Paul J. Rainey’s African Hunt. The 1912 release of Rainey’s film resulted in both critical and commercial success for Rainey and turned him into a screen idol who personified the mythical qualities of the “white hunter” – good looks, courage, sportsmanship and resourcefulness. Rainey had become a movie star.

Rainey’s African adventures were not over, however. Even though his film–work had met with success, he was obsessed with capturing a charging lion on film. Rainey approached Outram and Black about his plan and they declined, as did other professional hunters who were approached. Rainey was unable to interest anybody in his risky project until he became aware of a white hunter by the name of Fritz Schindelar.

Rainey’s African adventures were not over, however. Even though his film–work had met with success, he was obsessed with capturing a charging lion on film. Rainey approached Outram and Black about his plan and they declined, as did other professional hunters who were approached. Rainey was unable to interest anybody in his risky project until he became aware of a white hunter by the name of Fritz Schindelar.

In his book, White Hunters, Brian Herne notes that “what is known for certain about Schindelar is that he was not what he claimed to be when he turned up at Nairobi.” Although he claimed to be a “headwaiter and a baggage porter,” his knowledge of fine food and wine, sartorial style, skill at polo and ease in society all pointed to the conclusion that he came from a much different background.

Schindelar, by all accounts, was a womanizer, gambler and fearless. Although others had refused Rainey because they feared the effort would end in disaster, Schindlear readily accepted the challenge, whether for money or just from the simple thrill of the endeavor.

Rainy with his hunting party

The safari set out from Rainey’s Ranch about 80 miles west of Nairobi. Lions were prevalent in the area and so was the number of hunters who were trying to thin the cat population. As a result, the lions had developed nasty temperaments.

Rainey’s party was able to find and take lions, but they did not accomplish their core objective of filming a charge. But that was about to change.

In a rocky area where a large lion was seen, Rainey’s dogs started a big male that had most likely been hunted before. The lion headed for heavy cover and Schindelar tried to cut it off, but was unsuccessful because of the difficult terrain. From his vantage point atop a hill, Schindelar observed the lion and the pack, and saw how the cat occasionally turned and scattered the dogs before running off into the cover.

The lion reached a dense thicket where the air quickly filled with the sound of the baying dogs. Rainey set up his camera a short distance from the brush where Schindelar tried to provoke a charge by riding toward the thicket and drawing the lion out.

Schindelar rode to the brush, spun his horse, and raced away, but the lion did not follow. When he tried it again from a different angle, the lion attacked. The ferocity of the attack threw Schindelar from his saddle, and though he landed on his feet and was able to fire at the big cat, the lion was instantly upon him, tearing at his mid-section. The lion then charged Rainey and the rest of the party who opened up with a hail of bullets, killing the big cat.

Although Rainey was able to get Schindelar to a train and then a hospital in Nairobi, the damage inflicted by the lion was too great. Fritz Schindelar’s died within a few days, on January 26, 1914 according to the Kenya Gazette.

Despite the tragedy, Rainey continued his adventuresome ways. News that war had broken out in Europe reached Nairobi in August of 1914. Rainey tried to enlist, but was turned down due to health problems. Not to be deterred, he bought and outfitted an ambulance that he drove on the Western Front. Later in the war he put his photographic skills to work for the Red Cross.

Despite the tragedy, Rainey continued his adventuresome ways. News that war had broken out in Europe reached Nairobi in August of 1914. Rainey tried to enlist, but was turned down due to health problems. Not to be deterred, he bought and outfitted an ambulance that he drove on the Western Front. Later in the war he put his photographic skills to work for the Red Cross.

In 1923 Rainey was on board a ship sailing from England to Africa when he died on his 46th birthday and was buried at sea. His death turned out to be almost as dramatic as the rest of his life. Officially, the cause of death was a cerebral hemorrhage, but stories and rumors abounded regarding his demise. One story held that he had an argument with a stranger on the ship who cursed Rainey and told him he would not live to see sundown on his next birthday. Rainey died the next day.

Rumors also persisted that Rainey’s death was faked and there were enough alleged sightings of him to perpetuate the theory. In one story, a servant at Tippah Lodge recognized Rainey and called him by name and, although the man did not reply, he put a large bill in the servant’s hand and simply walked away.

George Outram and Alan Black ended up having their own troubles with lions. Outram was killed by a lion while trying to save another man from an attack. Alan Black was quoted as saying that he was, “fed up with shooting charging lions,” although he remained in the safari business until just before WWII.

For many years, Tippah Lodge remained vacant and maintained as it was when Rainey left on his travels. Gradually the acreage was sold off and finally, in the 1960s, the lodge and its contents were disposed of – the final scene in a life that rivaled a Hollywood epic.