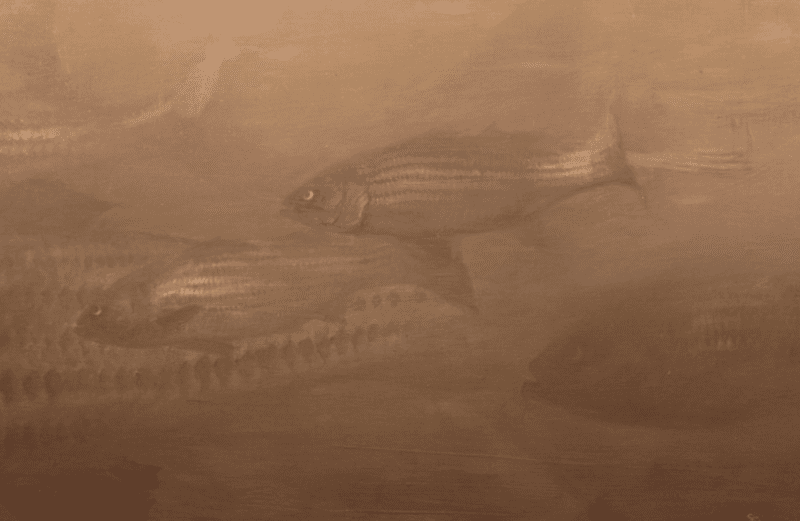

Roccus the striped bass had survived man’s hooks and nets and the ocean’s deadliest predators…and now, in her last years, she’d become the largest of her kind.

Sun and a wafer edge of dissolving moon rose a few minutes apart. From a late roost in a scrub oak on Blake Point, Nycti, the black-crowned night heron resented them hoarsely.

Roccus, a great striped bass, swinging a four-fathom curve and following a tide press, passed south of Centerboard Shoal and turned north. From deeper water she moved into nine feet off Bird Island. Spiny and soft dorsal fins slashed a V-ream in the stipple made by the breeze. Against a submerged granite boulder cored with magnetite, lightning-split from the ledge 500 years before, she came to rest, tail and pectorals fanning gently, at a meeting of tide and currents.

More them a quarter-century had passed since Roccus first rested beside the boulder during her original migration as a three-year-old in the company of a hungry thousand of her age and sex. To it she annually returned, sometimes with small pods of big fish, more recently as a solitary, in late May or June, when the spawning season of Roccus saxatilis ended and the eggs were spilled in the milt-chalked Roanoke above Albemarle Sound or, on occasion, in the region of Chesapeake Bay.

This resting place off the southern coast of Massachusetts was her domain until October’s northeasters sent her coursing southward. The boulder lie she had found good, and she returned to it as the experienced traveler returns time and again to tavern or hotel where he has found comfort and safety and food to his taste.

This year Roccus was making her earliest journey. For the sixth spring since she had attained a length of 16 inches, no urge within her belly set her coursing up the Roanoke or the Chesapeake feeders, past the thin tides to the gravel bars where, in other ecstatic Mays, she had reproduced. Instead, on the spangled night when the moon had waned, a counterurge had drawn her into the open Atlantic; and, passing migrating schoolfish too young to spawn, she had turned north and east along a thoroughfare as plainly marked for striped bass by current and tide and pressure, by food and temperature, by the instinct to avoid danger, as any broad, paved highway is posted for the guidance of man.

The migrating shoals of small stripers, or rockfish, or rock, had remained in the Barnegat surf when Roccus passed between Sakonnet and Cuttyhunk into Buzzards Bay and into the tides of the Narrow Land where Muashop, giant of Cape Cod legend, still blew the smoke of his pipe down a southwest wind to make the fog.

Now the 36-foot beacon of Bird Island caught the first rays of sun and splintered the dazzling light of new day. The moon paled and Mars and Venus and Jupiter were snuffed out in the sky of azure. Gong buoy 9, better than a mile to the south, winked green at five-second intervals. East, against the sun, the old Wings Neck Light lost color.

Roccus grooved her lie. She had come alone, too early, to a latitude of disquiet, troubled strangely, strangely drawn, and here in the merging, changing weights of waters familiar to the nerve ends along her laterals – in the surge of the sucking, thickening tide – she held her place while the light of the dying May moon transfused the direct stream of brilliance of which it was only a reflection.

In an overhang of the same boulder, behind a curtain of rockweed and moss and bladder wrack, on a scour of sand ground from granite by the tides of thousands of years, Homarus the lobster lay partially embedded and concealed, expelling water through 20 pairs of gills, her stalked, compound eyes fixed on the hinge of weed shielding her cave. Her two pairs of antennae rippled with the flow of the weeds in the sun’s first strike.

Homarus weighed 19 pounds and was nearly as old as Roccus. Since her final molt as a free-swimming surface larva she had shed shell, esophagus, stomach and intestine 17 times as her body became too large for the armor encasing it. During her years she had carried more than a million eggs glued to the flexed pocket of her abdomen. She was almost uniformly black, with tinges of green at her knuckles and streaks of chitin at the edge of her back shell. She was a cannibal and a glutton, vicious and ugly. In her youth she had made an annual crawl to deep water.

During recent years she had strayed little from Bird Island ledge. For her, as for Roccus, the boulder was a familiar lie, the lobster in the hole made by tide scour through the overhang, the bass above the overhang near the holdfast of the weeds. Homarus was secure in her knowledge that anything small enough to enter the cavern was prey for her appetite. The aperture was too small fix the green snout and jaws of the bass.

Each was aware of the other for hours.

Tide ebbed its extreme. In changing pressure, in degrees of salinity, in varying temperatures, there was conveyed to Roccus the memory of many feeding grounds. Around the boulder’s westerly side in slow pouring came drained warmth from shallows over lutaceous bottoms, a peculiar freshness tasting of algae, alewives, larvae and shellfish. This current was the confluence of drainage from Sippican Harbor, the Weweantic and Wareham livers, from Beaverdam Creek, Agawam River and Hammett Cove and a score of lesser waters into which anadromous fishes made their way.

Around the boulder’s easterly side swept an icy current from Cape Cod Bay, which plunged with the west-flowing current through Cape Cod Canal. This was underlay for a streak of warmer, less saline water which, on the flood, covered Big Bay and Buttermilk Flats and the Onset mudbanks, and had been freshened slightly by Red Brook’s discharge.

The separate currents ran and slowed, stirred and stilled, and there was a semblance of complete slack, a hushed suspension of motion.

Roccus turned outward from the boulder and the broad fan of her tail made a roil of water and sand, which parted the weed curtain of the overhang and caused Homerus to back deeper into her lodge, waving antennae in anger and spanning her crusher claw. Roccus resumed her lie.

The still of the sea was only an illusion; there was no dead calm. End of one tide was but the beginning of a new, and birth of the new tide aroused activity in the sea. Life about the ledge responded. Clams extended their siphons, clearing holes. Crabs settled carapaces deeper. Scallops thrust upward, dropped back like leaves falling through dead air. Sea robins changed lairs, crawling on the first three rays of their pectoral fins, and sculpins settled in the weed on the rocks, awaiting questing green crabs. Soft-finned rock cod moved lazily through caverns; and from countless hiding places the sharp-toothed cunners emerged in schools, nibbling at barnacles and the sand tubes of annelids. The cunners were the bait-stealing curse of bottom fishermen.

New tide awakened hunger in the lobster. Before Roccus’ arrival, Homarus had dined on a two-pound male of her own kind. Later she had killed a flounder, which by treading her legs, she had buried beneath her as a dog buries a bone for future reference.

Tide also awakened hunger in Roccus. She made a three-quarter leaping turn, a sprung bow of steel, and her tail drove into the overhang. Homarus, nearly dislodged, backed further into her cave, gripping deeper. The disturbance of Roccus’ thrust caused a surface commotion which excited seven herring gulls.

As the tide turned, Anguilla the eel swam to the ledge, surfaced, sucking larvae of a kind she had not tasted for seven years. Anguilla was a 32-inch ripple of macrurous grace, blue-black but showing yellowish-white on her underside in a transformation that would make her a silver eel returned from fresh water to the sea for completion of her catadromous life. She carried within her ovaries, moving down fresh water, more than ten million eggs, which would ripen swiftly when she reached the Sargasso deep. The urge to procreate swept her more relentlessly than any current.

As Anguilla approached Roccus’ lie and Homcuus’ lodge, she deflated her air bladder and sank close to the bottom, moving with slow undulation like a weed torn from anchorage. At the base of the boulder she came to rest, arrowed head near the weed curtain, a third of her elongated body curled beaneath her.

Homarus tasted oil from the eel. She withdrew her legs from the sand and buoyed her body and waved her antennae in excitement. She was fond of eels. Stealthily she extended her sharp cutter claw along the sand into the weed fringe.

Roccus saw the eel in the cone of vision of her gold-rimmed black left eye. She also tasted the eel’s oil.

Anguilla moved an inch nearer the hole, though appearing not to move. Behind the weed Homarus moved an inch nearer Anguilla. Roccus saw the lobster’s claw.

Though her superior nostrils sensed danger, Anguilla had no experience with lobsters or striped bass. She moved another inch, questing, tasting, testing. Her head, weaving, swung between the open jaws of Homarus’ cutting claw, which snapped like a trap. The cutter slashed embedded linear scales, flesh and bone, its blades meeting between the severed head and body of the eel.

As Anguilla’s body reacted in a hoop, Roccus made a violent tail smash against the weed curtain, and the compression dislodged the lobster, overturning her outside the hole. Before Homarus could right herself, Roccus overleaped and bit through her tail, crushing shell and flesh between double-toothed tongue and vomer plate.

In the strengthening of tide, Roccus lay content. She had eaten the tail of Homarus and all of Anguilla. The claws and body of Homarus bumped along the bottom in the quickening pulse of the sea, all but concealed by a cloud of cunners, some already inside the body.

Three days later her body shell, first crimsoned, then paled pink by the sun, was found on Indian Neck by a boy who showed it at home to the amazement of his parents. They had never seen one so large. The boy saved it a few days, but it grew rank and his mother made him bury it in their garden, where, in August, it fed a clump of coral phlox envied by all their neighbors.

Out of the southern sky, against the afterglow of sun when flashes of the Wings Neck Light grew bolder, a wedge of birds come driving beneath the first sprinkling of stars. They flew in wavering formation, 18 on the light flank, 20 on the left: Canada geese seeking rest. They were in flight from Texas to Crane Lake in Saskatchewan and since daybreak they had been on wing. Cutting across Cape Cod, hey flew at 2,000 feet with a following breeze. As they passed over Bird Island the gander leader sighted the distant sheen of Big Bay and Little Bay, Buttermilk and Great Herring, and the mirrored, shadowed surfaces of Sandy and Long Pond and Gallows and Bloody and Boot, and a score of others. He honked and towered, circling, climbing, then all the flock began to honk and gabble, their voices like those of beagles chasing rabbits among the constellations.

Out of the southern sky, against the afterglow of sun when flashes of the Wings Neck Light grew bolder, a wedge of birds come driving beneath the first sprinkling of stars. They flew in wavering formation, 18 on the light flank, 20 on the left: Canada geese seeking rest. They were in flight from Texas to Crane Lake in Saskatchewan and since daybreak they had been on wing. Cutting across Cape Cod, hey flew at 2,000 feet with a following breeze. As they passed over Bird Island the gander leader sighted the distant sheen of Big Bay and Little Bay, Buttermilk and Great Herring, and the mirrored, shadowed surfaces of Sandy and Long Pond and Gallows and Bloody and Boot, and a score of others. He honked and towered, circling, climbing, then all the flock began to honk and gabble, their voices like those of beagles chasing rabbits among the constellations.

Nine miles away, coursing a meadow where quail had roaded, a dog fox heard the geese and cocked mangy ears. Saliva drooled from his mouth because once he had tasted gosling in the yard of a farmer. Fear rose in his heart because he had met ganders, to his sorrow. He stood silent, listening, pretending not to listen.

The geese reached peak of tower and the old bird made his choice, which was Little Bay where the eelgrass was thick. Honking ceased, the wedge drove north in silence, losing altitude. The fox did not hear the geese again and was relieved that his appetite would not place a strain upon his fortitude. He wet where the quail had been and went off to hunt a mole.

Until the tide turned, Roccus occupied her boulder lie, at times suspended in the current, at times on the scour outside the empty lodge of Homarus.

Saturn was the evening star. The moon had crossed the meridian with the sun and was invisible from earth; it was dark o’ the moon. When the blanket of stars lay close and heavy on the water, shimmering and opalescent, Roccus broke through it with a roll and tailslap and fell back on her side. The star scattered, danced, reformed in wavering pattern. The bass slashed the surface, sinuating on her right side, then on her left, leaped half clear. Three yellowish-brown sea lice fell from her shoulder and were promptly devoured by a cunner, which an hour later was eaten by a crab which, before morning was swallowed by a master sculpin.

Nycti the heron, belly yearning, flapped from the filth of his roost for a night of hunting in Planting Island Cove. His flight voice was harsh; quuaawwk, quuaawwk!

Roccus leaped once more in the brief sustension of the tide.

From Dry Ledge, Roccus drove northwest again seeking warmth. Alewives were in abundance but their appetite was held in check by enervating cold. In the livers a few bass that had wintered over began to lose sluggishness.

On a morning ebb there was a definite change of pressure and the wind backed into the northeast. Roccus swam to the sandy shoal between Warren Point and Long Beach Point, lay finning in three feet of water. Even the hermit crabs had moved off the shoal in advance of the storm. The wind made up and the surface ran angrily in lifts, sulkily in hollows, and Roccus gave herself to the conflicting movement of the water, warmed by water thinned by rain.

Half buoyant, she was vibrant with storm, knowing it with all her body, comforted by its warmth; she was of the storm as well as of the sea. Wind pushed against the tide, tide pushed the surface; the surface waters ran counter to the movement of the tide. Roccus lent herself to the opposing actions and in the turbulence maintained her lie without effort, now feeling the scrape of sand against belly and anal fins and tail, now delighting in the lash of raindrops along her dorsal.

By slack of ebb the wind was a halfgale and seas ran more regularly and higher over milky sands. Roccus dropped back into deeper water. The first northeaster of the reluctant spring gathered force from a thick, gray ceiling of clouds.

Nineteen Years to Sunrise by Michael Altizer is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now

Nineteen Years to Sunrise by Michael Altizer is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now