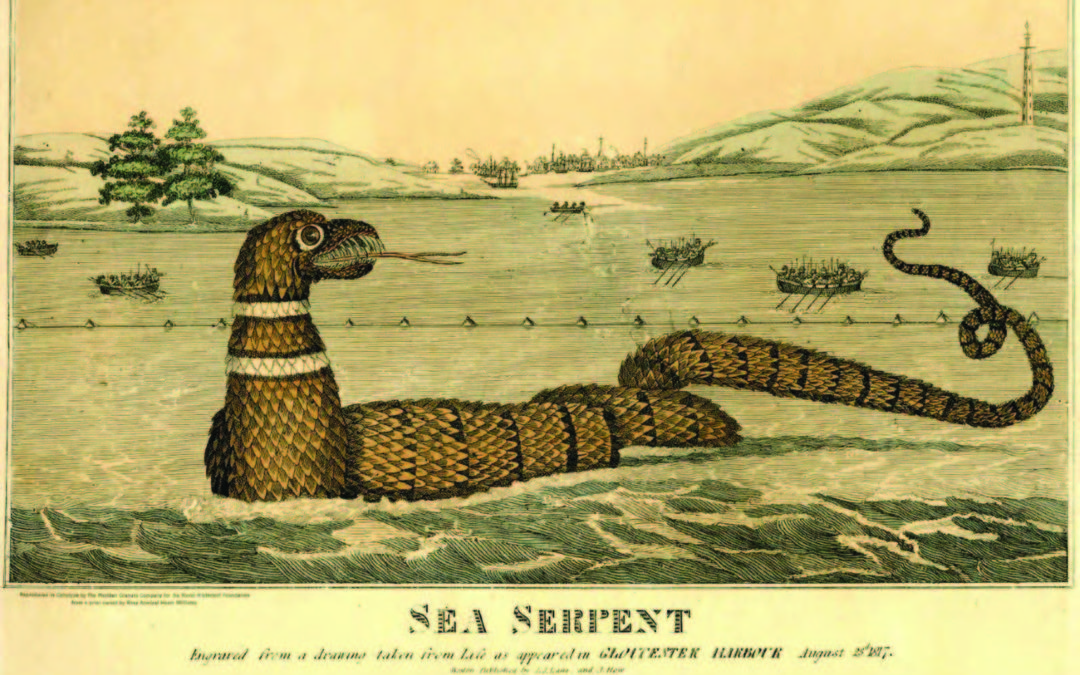

We were told how it was seen by two skippers commanding separate vessels off Gloucester and—how it approached one of the sails, as if for the purpose of attack — how its eyes were fierce and fiery — how its head, large as a flour barrel, was raised three feet above the water—how its length was from 90 to 120 feet — how its back, while it moved along, presented the appearance of bunches which projected above the surface, and how, after approaching within 50 yards of the vessel, it dived beneath it and disappeared, to the unspeakable relief of the crew!

It seemed impossible, from the mass of corroborative testimony, to question two important facts — first, the existence of this strange and formidable animal, and second, that it took the form of a serpent! It was no myth, but an actual, living, formidable, unchronicled monster of the deep. In the excited state of the public mind, expeditions were planned to capture it and put to rest all future incredulity by exhibiting it to the gaze of the people.

It seemed impossible, from the mass of corroborative testimony, to question two important facts — first, the existence of this strange and formidable animal, and second, that it took the form of a serpent! It was no myth, but an actual, living, formidable, unchronicled monster of the deep. In the excited state of the public mind, expeditions were planned to capture it and put to rest all future incredulity by exhibiting it to the gaze of the people.

I remember dining, during this excited state of the public mind, with Dr. Robbins of Boston at his cottage at Nahant. I well remember the sumptuous fare spread before us by our hospitable host — the delicacy of the viands, the lusciousness of the fruits, the richness of the wines. But what I recall with more especial pleasure is that Prescott, the historian, was among the guests and charmed every stranger present by his colloquial powers, and by a modesty of deportment that sat on him too naturally to have been assumed. By my side, too, sat my early friend and cherished classmate, Francis C. Gray of Boston — now, alas, no more! — the refined gentleman, the accomplished scholar, the keen, discriminating writer whose unnumbered kindnesses come crowding thickly on my memory as I recall his name — and dim my eyes, while I write, with tears!

The cottage of Dr. Robbins was seated on the very cliff and overlooked the sea. The cloth was hardly removed when a murmuring noise from without induced us to look out, and we observed that the adjoining rocks were being fast populated by an anxious crowd, who were looking intently toward the sea. Our eyes took the same direction — there, on the smooth surface, lay the sea serpent!

There was the ripple, there were the bunches — just as they had been described in print; there was the long wake, leaving it uncertain what was the actual body and what represented the displacement of the water caused by the rapid motion of the animal.

An excitement seized upon us all, and obeying an impulse that my former training may well explain, I resolved to volunteer with any party that should attempt its capture. Meantime the serpent disappeared, and when he next presented himself on the surface we brought a telescope to bear on him and found to our infinite chagrin that the object, which magnified by the haze of the atmosphere had seemed to us the veritable sea serpent, had now shrunk to the dimensions of a despicable horse mackerel!

“But surely, sir, you have mistaken your latitude—you are adrift without a compass! What have you to do with the sea serpent? He is the peculiar property of New England; he never condescends to show himself elsewhere. He is of the Pilgrim States; their very specialty, as much and as exclusively theirs as the gift of witchcraft, the privilege of detecting it, and the divine right of punishing it. With what propriety, therefore, can you pretend to introduce him in a book of “Carolina Sports?”

Have patience, most choleric reader! Patience is a piscatorial as well as an apostolic virtue, as needful (you may find) to the reader of fish stories as to the fisherman himself. Patience, and we shall see.

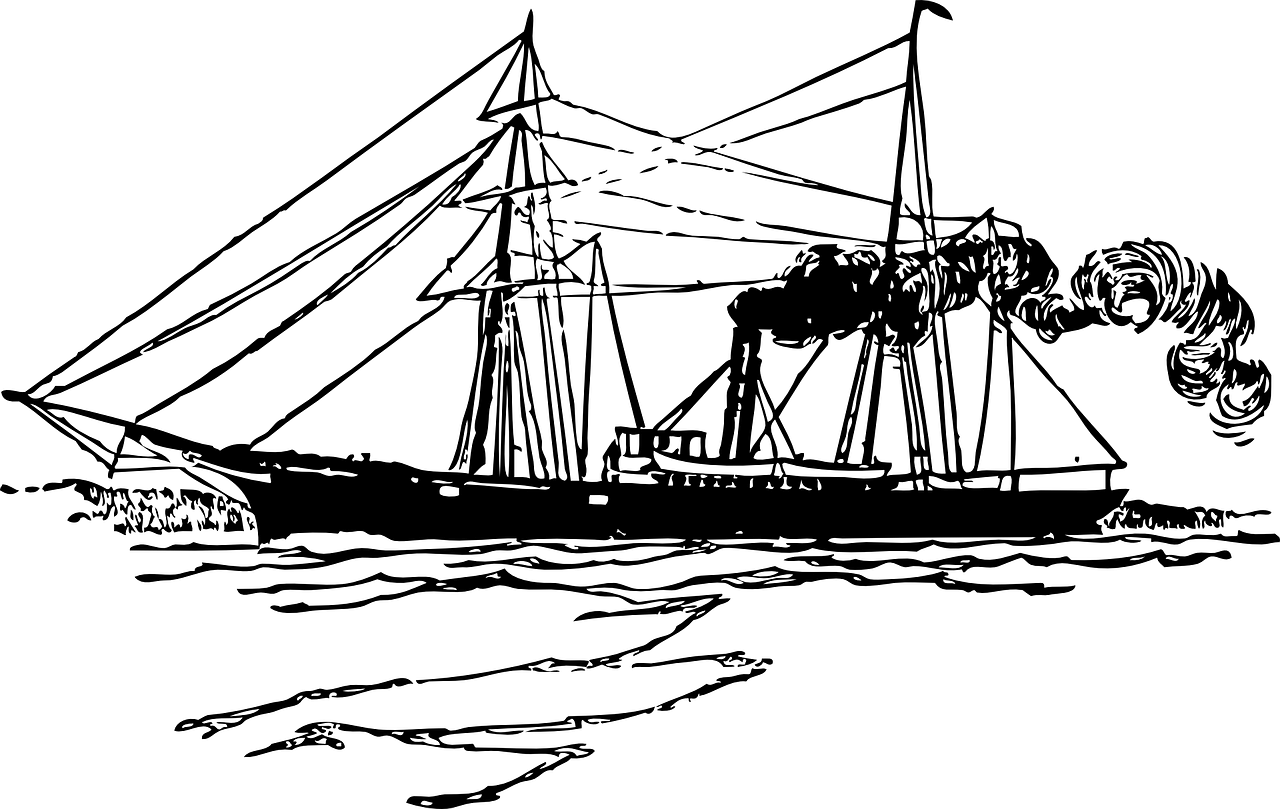

The March winds were whistling sharply, as is their wont, along the southern Atlantic seaboard when the gallant steamer Wm. Seabrook loosed her hawser from the wharf at Savannah, to which she had been moored, and pressed forward on her inland voyage to Charleston. At her wheel stood her stalwart commander, Blankinsop, long known and well reputed in all the region roundabout.

The steamer glided through the yellow waters of the Savannah River, between fields of rice enriched by deposits from these same turbid yellow waters until they rivaled Egypt in fertility. And well they may—while only one annual inundation enriches the Egyptian soil, here, twice in the short life of every moon, are these fields refreshed and renewed by fertilizing floods.

The steamer approached the sea, whose salt tides contend for mastery with the fresh waters from the high lands, which, having long held undisputed possession of the channel, are now urging boisterously their exclusive and prescriptive right against the encroachments of the ocean. She wound along the corkscrew channel — worn by the contending tides in the soft, oozy bottom — and weathered the black-oyster rocks, then rounded the tail of Grenadier Bank, with its flankers of snow-white breakers. Then she bore up for Callibogue Sound and passed the mouth of the river of “May” — Laudonniferes’ river of that name, or else wrongfully baptized in it by some bungling geographer; then with rapid strokes she dashed through Skull Creek — Hilton Head on the starboard, Pinckney Island on the larboard bow — till all at once she emerged on the broad, deep estuary of Port Royal, already familiar to the reader as the sporting ground and battleground of the devil-fish!

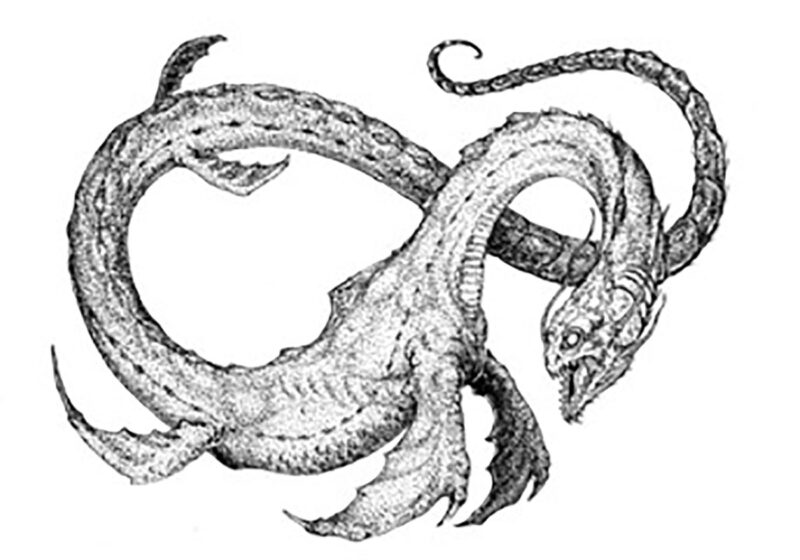

The steamer merrily dashed the foam from her prow — weathering the tail of Paris Bank, and pointing up Beaufort River toward the town of that name — when lo and behold, what startling spectacle then met the gaze of the astonished commander! What but the veritable sea serpent, tired, we may suppose, of the monotony of his northeastern haunts, was amusing himself with an excursion to the South and had looked in (en passant) on the pleasant harbor of Port Royal! Mars and Bellona! What did the captain do? There lay alongside of him this leviathan of sea monsters, “long as his steamboat, stout as his yawl.” There he lay in his interminable length, his bunches all visible (as may be seen on the frontispiece of many a veracious pamphlet of the day), each several bunch of the series set down by authority, and verified by a Gloucester affidavit!

What did the captain do? Why, like a prudent and considerate commander, he did not do what you or I, in a daredevil spirit, might have done — he did not attack the monster! He would not risk the owner’s property, you see! If he attacked the strange craft, and came to damage it, he might forfeit insurance, for this risk was not put down in the policy! So, giving the monster a wide berth, he turned tail, blew off three terrific blasts at him from his steam whistle, and drove away for the town of Beaufort as if the devil himself was in his rear!

The captain had no sooner reached the wharf, and disclosed his startling intelligence, than the whole town was aflame with excitement!

The captain had no sooner reached the wharf, and disclosed his startling intelligence, than the whole town was aflame with excitement!

“What is this?” said a fine-looking burly gentleman who came bustling down with an air of official authority about him. “What hoax are you playing off on us? The sea serpent in Broad River! Tell that to the marines!”

“As sure as you live,” said the captain, “I saw him two hours ago.”

“The hell you did! Why did you not hawser him and bring him up to town?”

“He was as large ’round as my yawl boat and as long as the steamer,” said the captain, explanatorily.

“The old one, of course,” said the stout gentleman. “But what should the devil or any of his deputies find to do in these waters? I should be glad to know! Didn’t the saints make such a clean sweep of us some years back that this devil of a subject could no longer be found among us?”

“I don’t know that,” said a keen-looking, ascetic man in a quiet tone. “He might get some, from what I hear, by voluntary enlistment!”

“The captain took an afternoon observation,” hinted one.

“Twilight magnifies,” said another.

But in spite of jeers and doubts, the captain’s testimony was positive, earnest, and unvarying, and the conviction soon became general that the monster was really in Port Royal! Then came the unanimous determination to capture him at all hazards!

“We’ll teach this Yankee craft to cruise in our waters,” said one.

“Doubtless, he has his belly stuffed with abolition tracts,” said a hungry-looking secessionist, leading off on the grateful scent.

“Gentlemen,” said a third, “the sea serpent is here — that’s a fact. We must capture him; that’s another fact, or soon will be. Who’ll volunteer? He shall not insult us by his presence in these waters—us, who have encountered and beaten the devil-fish, who are his betters for aught we know — us, who have trailed behind them all night in our undecked skiff, on the open sea, and mastered them with the rising sun. We’ll kill him, gentlemen; we’re the boys to do it.” And it was resolved!

The steamer, whose intelligence had caused such unwanted commotion in this ordinarily tranquil town, now steamed off for her destination, unconscious of the ferment she had excited.

Oh, Beaufort, thou mother of beautiful women and illustrious men, who devotest thy daughters to Heaven in this world and the next but dismissest thy sons in the opposite direction! Thou unmatchable town, whose mansions, streets, and roads are all of shell-work; that blindest the eyes of thy people with concrete dust, and with concrete walls defendest thyself against the approach of thy enemies! Thou mathematical paradox, whose angles become right lines by “order of council,” and whose right lines are as tortuous as angles! Thou financial wonder, whose taxes increase as thy means diminish, and whose inhabitants grow rich by borrowing from each other!

Oh, Beaufort, lovely always, but like a freckled beauty, loveliest at a distance! What a storm of excitement burst over you on this eventful night and startled you from your accustomed somnolence! There was many a lovely eye that did not close a lid for fear of the encroachment of the serpent! There was many a manly heart that waked as well, but throbbed with impatience to grapple with and subdue him! They did not sleep; long before midnight the lieges of Beaufort were afloat, intent on mischief.

Oh, Beaufort, lovely always, but like a freckled beauty, loveliest at a distance! What a storm of excitement burst over you on this eventful night and startled you from your accustomed somnolence! There was many a lovely eye that did not close a lid for fear of the encroachment of the serpent! There was many a manly heart that waked as well, but throbbed with impatience to grapple with and subdue him! They did not sleep; long before midnight the lieges of Beaufort were afloat, intent on mischief.

Prominent among them was Capt. J.G.B., once the honored captain of the Beaufort Volunteer Guards — now the commander of the consolidated corps of artillery and guards; he was to command the artillery of the expedition. A man of honor and worth was he; a high-toned man whose only quarrel with life was that his military aspirations had never been gratified; that his misgoverned country had never indulged in the luxury of war, nor afford him the opportunity for that distinction for which his soul pined!

“Here is a chance after all,” said the captain, rubbing his hands. “It is not war, but something almost as good!”

Then there was Captain G.P.E., captain of this same artillery; he was to command the squadron. Confident was he of making mincemeat of the sea monster! Had he not driven bayonets and pikes and harpoons innumerable into devil-fish? Was he to be daunted now? No, not he! He would draw the serpent’s teeth and leave them in pawn with his friend who swore so terribly! He would give its flesh to the sharks — its skeleton to Dr. — in exchange for a unicorn, or to his friend the colonel, in exchange for his favorite mermaid! Its skin he would present to the museum at Salem, to be exhibited gratis to the enterprising people of Gloucester, and in exchange, if they could find one, for the skin of a witch.

They launched a flat, which in consideration, of his known antipathy to serpents, they dubbed Saint Patrick, and in it embarked Captain B. with his six-pounder, well supplied with ammunition and with a select squad of artillerists to serve it. Next came Captain G.P.E. in his sailboat, The Eagle, with a lighter armament, but endorsed by an apparatus fitted for devil-fishing, with harpoons, ropes, and buoys. Lastly came a skiff to ply between the heavier boats and pick up stragglers, should any be tossed overboard in the expected fray. Here was good strategy — an anchor to windward, a loop-hole for retreat, were it necessary, and security for some, at least, of the assailants, for it would be difficult for his highness, even with all his imputed fierceness and voracity, to take down three boats at a gulp!

Full of spirit, and of high hope and expectation, the party now embarked and went merrily on its way with wind and tide in their favor, until at dawn of day they found themselves on the waters of the Broad River, by the way of Archer’s Creek. They cast their eyes wistfully east, south, and west over the wide expanse, but no serpent was to be seen. They agreed to divide and signal each other should either party come in sight of the enemy.

Saint Patrick, with the skiff in company, passed up the river with the tide. The Eagle spread her wings and sailed away to seaward, against the tide. After sailing on that tack for some time without seeing anything unusual, she turned to rejoin her consort, who had now made an interval of several miles between the boats.

Suddenly the lookout boy stationed in the bow of The Eagle called out, “I see something ahead!”

“Where?—where?” and all hands rushed to the head of the boat to see, and beheld close abroad of them an object like a boat turned bottom-up.

“Gentlemen,” said Captain George, “look out. The object is right ahead — but a hundred yards off. We shall be in the jaws of the serpent before we can stop! Helm down.”

The boat would not answer the helm; there was too much live weight at the bows.

“To your places, gentlemen! Let go sheet ropes!” She fell off from the wind, and the boat passed, just without touching, the object that had called forth this sudden commotion.

“Very like a whale,” cried Captain George as he gazed at the unknown. “Look there! Another; we’re in a shoal of whales! There’s five of them; three full grown and two young ones! No sea serpent after all, but game. Royal game, too; a perfect godsend to us. Let us signal our consort and bring them to action.

“Ah, Saint Patrick! That habit of yours of taking it easy and going with wind and tide has brought you into trouble! These four miles of headwind and tide, and hard tugging at the oars, before you can face he enemy, all come of this obliging disposition of yours!”

“Ah, Saint Patrick! That habit of yours of taking it easy and going with wind and tide has brought you into trouble! These four miles of headwind and tide, and hard tugging at the oars, before you can face he enemy, all come of this obliging disposition of yours!”

The whales, too, were going against the tide, so that the match was not so very unequal after all, and Saint Patrick, after a hard tug, with a swaggering air that seemed to say, “All right now, won’t I take the conceit out of you?” ranged up alongside the enemy, and when he had got within a hundred yards, let go a six-pound ball at the first whale that showed himself above the water.

“They take no notice of us!” said the baffled artilleryman.

“Try another shot.” They tried another and another, but the balls went dancing and ricocheting over the waves innocent of blood. No wonder! The wind blew high, the sea was rough, and the Saint Patrick (shame on him) was a little unsteady!

“Now, Slowman,” said Captain B., “try your hand. Your father was our crack shot, and you boast that you can bring down a sparrow on the wing with your six-pounder. Show us your skill, now!”

“Well, Captain, but a sparrow on the wing is easier than a whale underwater, but here goes!” He rammed down a canister of grape, and when the next whale rose, a shower of balls flew about its head.

“Ha, ha! He feels us now!”

The whale flung his fluke aloft and brought it down on the water with a report that rivaled our cannon, then plunged downward. When he next showed himself on the surface, there were some keen-sighted sportsmen aboard who averred that they spied a hole in his jacket and a piece of blubber fat sticking out of the orifice!

Meanwhile the whales began to move at increased speed toward the sea, and it became doubtful whether the Saint Patrick could retain his position so as to continue the action.

“Come,” said Captain George, “they must not escape us. I’ll go in the skiff and tackle them with my devil-fish harpoon. Who’ll steer the skiff? I’ll take two boys to row.”

So off they start: Captain George, at the bow, while two hands pulled vigorously at the oars. The ripple caused by the motion of the whales against the current showed their direction even while they were submerged. The whale had no sooner emerged than the boatmen were ordered to pull right in for his head. The boat actually touched him when Captain George struck the harpoon into his head, and as the whale seemed stunned or insensible, he drove it in with both hands till the skiff recoiled with the force of the blow.

Thirty fathoms of rope, attached to the harpoon, had been wound ’round a cask, which was now thrown overboard, and the cask began to spin around in a marvelous manner until the whole line was unwound, when it went bobbing under and reappearing with the rapid or slower movement of the whale.

Three cheers went up from the assembled sportsmen at the execution of this daring feat; high hopes were entertained that they would succeed in capturing the whale. The whale, meanwhile, floundered and plunged and lashed the water with his powerful fluke, whirling over while on the surface until the rope was observed to be twisted several times round his body, while the staff was seen sticking from his throat. The sportsmen, in their three boats, followed closely in his wake, waiting for him to exhaust himself, and in the interim, betook themselves to breakfast.

Suddenly the cask became motionless. They approached, pulled upon the line, and, to their deep mortification, discovered that the harpoon had drawn out.

“Now is my turn,” said Captain John. Taking his place in the skiff, he repeated the exploit of Captain George—he struck a whale with great force, which, like its predecessor, contrived, after a short struggle, to rid himself of the harpoon.

“My turn is come again,” said Captain George. Planting himself a second time in the bow of the skiff, he struck his harpoon deeply, this time, in the body of the whale. Again were witnessed the furious plunges and contortions; again the harpoon tore out, and the baffled sportsmen, on the failure of this, their third cast, had to confess to themselves that their tackle was inadequate to the capture of a whale.

The wind now veered to the east, and a rainstorm set in, so that it was necessary to draw off from the enemy and make a harbor for the security of the boats, and especially of that which was burdened with a piece of artillery, which was accordingly done.

The next day was Sunday, and our sportsmen did not follow the example of the commanders of modern Christian armies, who apparently select that day for an engagement. They stayed at home and retook their positions on Monday, with better knowledge, better equipment, and in every way better prepared for success. But all too late—the enemy had fled! The captain of a coaster met them on their retreat as they left the harbor; nothing more was heard of them, except that rumor reported one of them as having been stranded on the island of Kiawah.

When, during the pursuit of these whales, the beasts occasionally threw themselves in line, following in each other’s wakes near the surface, with their fins projecting above the water, the close resemblance to an immense serpent was brought strikingly to the minds of our sportsmen. It was easy to perceive how, in a hazy atmosphere or during an agitated sea, the sporting of a shoal of whales might (by the mind of an excited mariner) be honestly mistaken for the redoubtable sea serpent!

When the expedition returned to Beaufort, there were some to taunt it with its want of success.

When the expedition returned to Beaufort, there were some to taunt it with its want of success.

“Well, Captain George, where is your prize? You have not caught the whale, after all.”

“No,” says Captain George, “but we have done better. We have killed the sea serpent!”

Editor’s Note: “The Sea Serpent” originally appeared in Carolina Sports by Land and Water, first published in 1867.

In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now

In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now